Catching up with Billy Mills

Billy Mills was 12 years old and growing up on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota when he was orphaned. He remembered the words of his father, an avid storyteller: You have to look deeper, way below the anger, the hurt, the hate, the jealousy, the self-pity, way down deeper where the dreams lie, son. Find your dream. It's the pursuit of the dream that heals you.

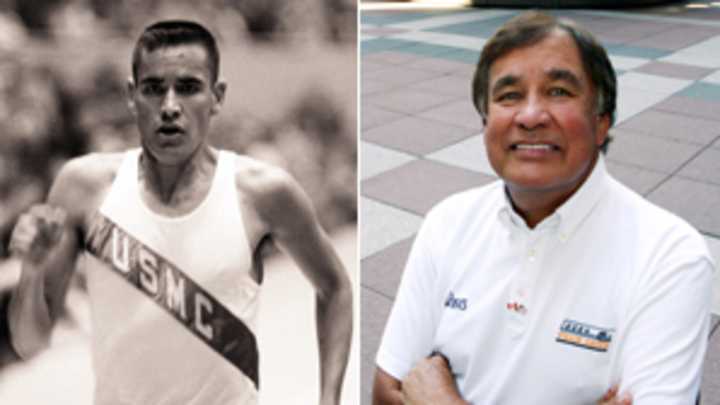

"All I had was the pursuit of a dream: I wanted to be an Olympian," said Mills, 69. He tried a number of sports, including boxing and football, but soon found his calling in running. Mills went to Kansas on a track scholarship, then enlisted in the Marine Corps. In 1964, his dream propelled him to Tokyo, where he set an Olympic record (28:24.4) in the 10,000 meters and became the only American to win a gold medal in the event.

After his victory, considered one of the greatest upsets in Olympic history, Mills returned to the Marines to complete his final year of commission. He just missed deployment to Vietnam. Instead of feeling relief, Mills, a Lakota Sioux, said he felt guilt.

"In Native American culture, if you bring pride and respect to yourself, you are asked to give back to the people who helped you," he said. "It's called a 'giveaway.' I decided that my giveaway would be the inspiration that was given to me. I'd pass it on to another generation."

Mills started selling insurance and began telling his story to sales and marketing groups across the country. In 1983, Hollywood allowed him to reach a wider audience with the release of Running Brave, a movie based on his life. Promoting the film led to more speaking engagements and advocacy opportunities.

In 1986, Mills met Gene Krizek, president of Christian Relief Services, who had a passion for Native American causes but no means to fundraise for them. It was a perfect partnership: Mills became spokesperson of Krizek's organization, and together they founded the spinoff charity Running Strong for American Indian Youth, which supports cultural programs and provides health and housing assistance for Native American communities.

Mills estimates the group has raised close to $100 million. "It's a tremendous feeling, knowing that one moment in time, winning a gold medal at the Olympic Games or just crossing the finish line can structure a way in which you can give back and affect multitudes of lives worldwide, and especially in your own community," he said.

By 1990, Mills retired from insurance and was working full time as a public speaker through his own business, the Billy Mills Speakers Bureau, based near Sacramento. At the same time, he and his wife, Patricia, decided to expand Mills' storytelling to another medium, and invited their office secretary, a talented young man named Nicholas Sparks, to co-write with them Lessons of a Lakota, an allegorical tale inspired by Mills' childhood.

"When Nicholas wrote the book with my wife and me he said, 'Wow, writing's my new passion,'" Mills said of the now-bestselling author.

Mills has spent more than 290 days on the road over the past 11 years, doing about 70 annual talks for companies, schools and various panels. He plans to taper off his appearances over the next two years and go into "semi-retirement," although he will stay active with Running Strong.

Of course, Mills' most cherished achievement is his family. He and his wife have been married for 46 years and have four daughters and nine grandchildren, although they count 17 kids, including Sparks' kids, who call them "Grandma" and "Grandpa." Mills said that he is most proud of his 4-year-old grandson, Dominic.

"He was born at 31 weeks, and when you're born premature, you don't develop the intricate muscles for speech, so you have to be taught to speak," Mills said. "Last year, Dominic was having trouble learning to call his grandfather. He would try to call me 'Papa,' but he didn't have the strength to finish the word, so he'd just go 'Pa,' and then no word would come out. He'd hit his left forearm with his right fist and go 'Pa pfff...'

"Finally one day he goes, 'Pfff... pfff... pfff... pa pa!' Oh my God, that was just one of the most beautiful moments of my life. His eyes watered and mine, I started crying and he looked up and had a glow on his face. I thought, My God, that journey for him to get there was every bit the journey for me to win the gold medal. So I gave him my gold medal."