The slow descent of Houston McTear, the greatest natural sprinter ever

I loved to run, that’s all I wanted and have peace, I wanted to paint the track with my body all over the world, I could feel it in my soul, that’s where I belonged.

– Houston McTear (1957–2015)

Houston McTear once recalled May 9, 1975 as “a great day for running ... it was really hot, something like 105 or 106 degrees ... I told my teammates before the race I felt like thunder and lightning at the same time.”

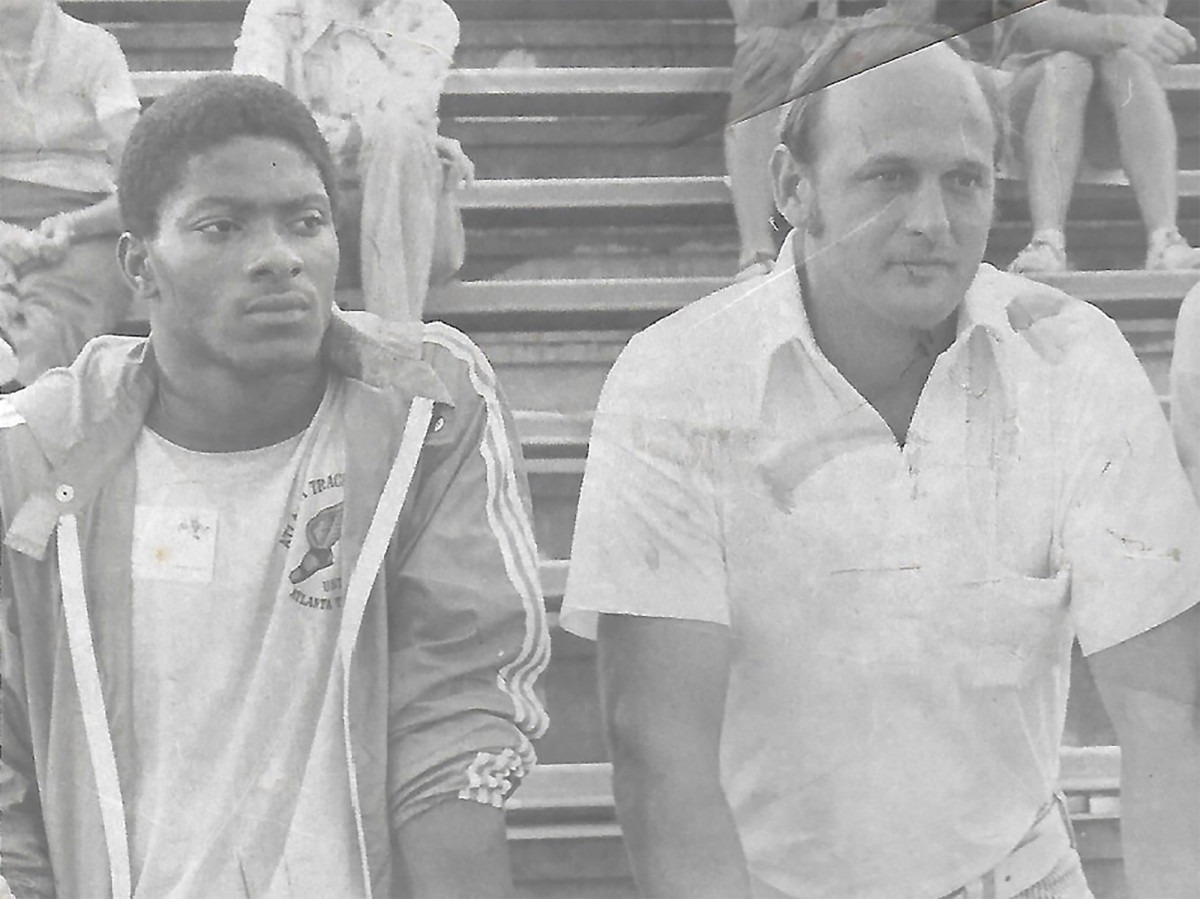

Standing near McTear that day was his coach at Baker (Fla.) High, Will Willoughby, a balding, 6' 3" bear of a man who had driven eight teenage runners to that state championship meet in Winter Park, just outside Orlando—a five-hour drive from rural Baker in his rusty van. Four of those eight kids were named McTear, members of an outlier family that ran faster than anyone had ever seen a group of relations run. Of those four McTears, two, George and his younger brother Houston, lived at a level of poverty that surprised and saddened every outsider who laid eyes on the two-room shack by the saw mill where they lived with their parents and six siblings.

*****

There is no known video of the preliminary heat in the 100-yard dash that 18-year-old Houston ran that day in Winter Park. But the accounts of those who were present illuminate an achievement that—considering our post-millennial passion for scouting and “developing” athletes at increasingly younger ages—would be impossible today, and will almost certainly never happen again. A teenager with no formal coaching (other than that provided by the well-meaning Willoughby, who was more of an uncle and chauffeur), a kid who averaged one good meal a day and if he was staying true to form had smoked a Kool filter king just before the race, tied a world record in a sprint event, running the length of a football field in nine seconds flat.

The 300 or so spectators at Showalter Stadium fell quiet. Did the P.A. announcer just say world record? Not state or meet record?

The accomplishment was so unthinkable that it would not be made official until a months-long investigation had been completed in California. Unfortunately, the Accutrack timer at the finish line when McTear whooshed past was being used at that state championship meet only as a camera, to decide close finishes like the 3A final, won by a lanky kid from Titusville named Cris Collinsworth. Confirmation of McTear’s record would depend on the three men who stood at trackside, stopwatches in hand, deciding whether they believed that this 5' 7" kid from the sticks had just tied the record set by 25-year-old Ivory Crockett, whose 9.0 the year before had nipped the legendary 9.1 that Bob Hayes ran in ‘63.

“I couldn’t believe it when I first looked at my watch,” timer Paul Herman told the Orlando Sentinel in 1985. (Herman died in 2009 at age 92.)

“I figured it couldn`t be right,” said Jim Moreland, another of the three timers.

“My first reaction was that they must have used the wrong starting line,” Jim Vickers, the head judge, told the Sentinel. “We really didn`t know what to do.”

Retired sportswriter Bill Buchalter, one of the deans of Florida newsprint, recalled earlier this summer that when he made his way forward and saw those watches for himself, “I excused myself and said I had some phone calls to make.”

*****

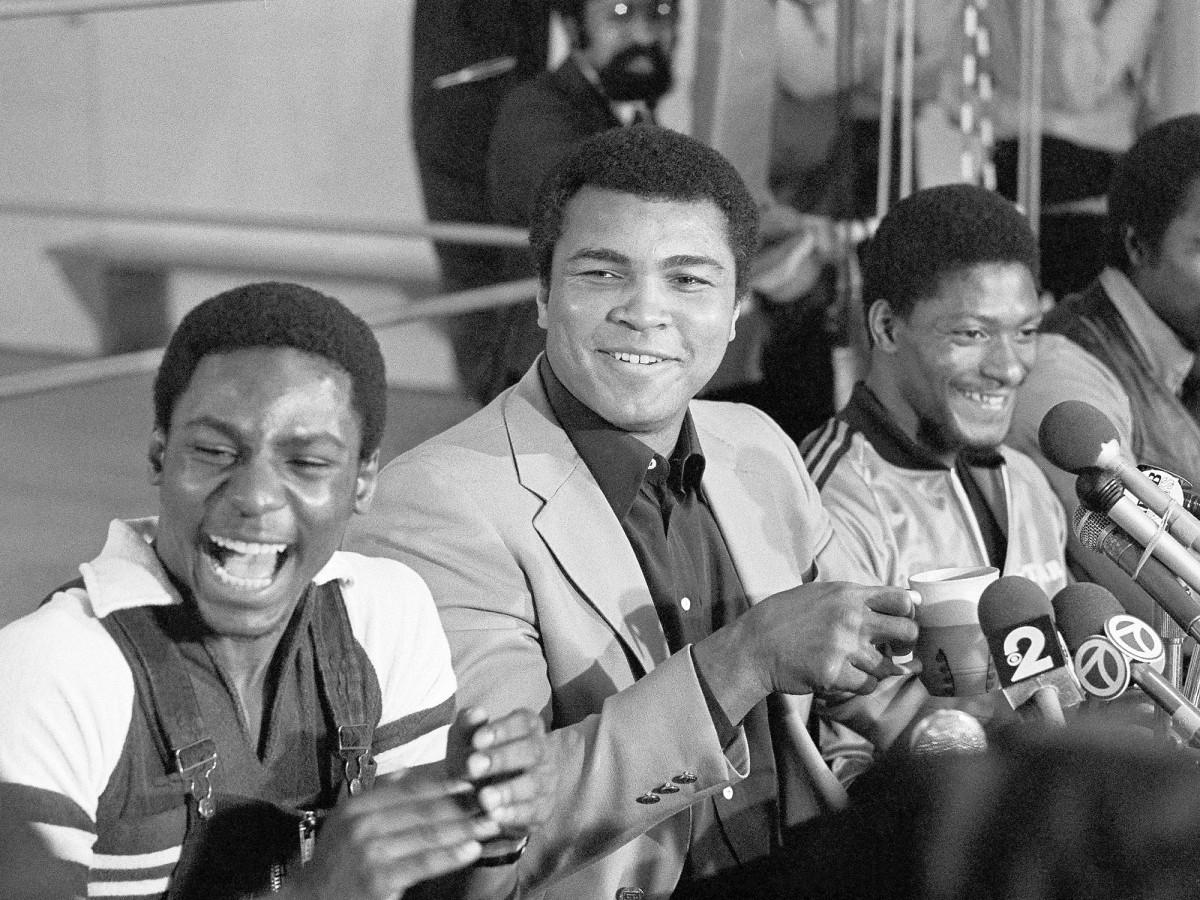

Houston McTear’s improbable 9-flat would turn out to be one of many improbable events in his nearly six decades of life, a life that grazed the Olympics twice, but, by no fault of his own performance, never broke through. At the height of his fame, McTear’s life was funded by Muhammad Ali and a con man whose scamming skills were as world-class as McTear’s sprinting and Ali’s punching. McTear’s life included years of sleeping wherever he ended up—on the beach, in a shelter, most nights huddled under a cactus. Its most implausible moments came shortly after those days ended.

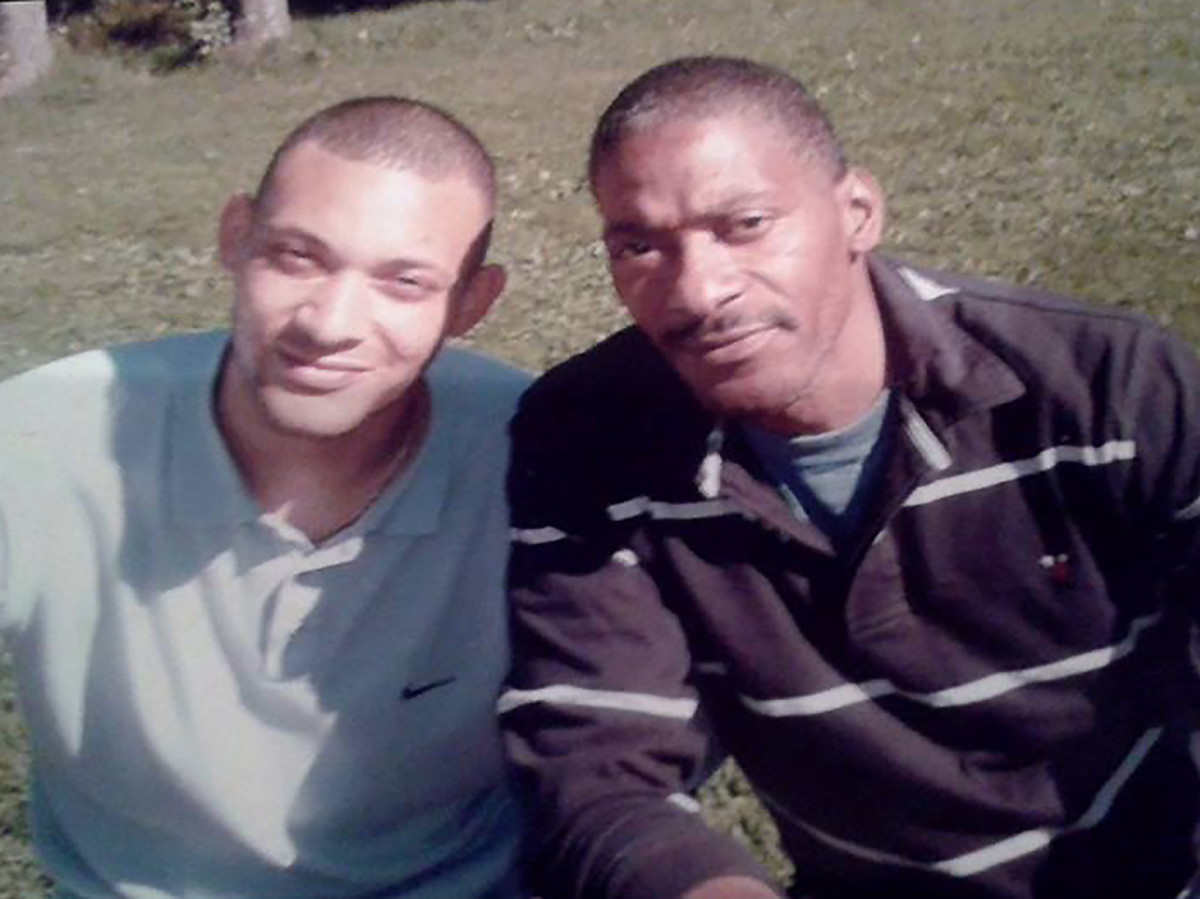

“More than anything,” says Isaac McTear, 38, the oldest of McTear’s three children, “it’s a story of humble beginnings.” Sipping tea in a London hotel, Isaac is a lighter-skinned clone of his father, from his half-lidded eyes to the calf raise he does reflexively at the end of each step. “It’s a story about going from one extreme to the other. My dad probably could never have imagined when he was a child that he might find himself on the world stage, as shy as he was, with all the lights and cameras on him. So many expectations …”

Olympic medal predictions: Picking gold, silver, bronze in all 306 events

*****

The house where Houston McTear grew up isn’t there anymore. It was overtaken and eventually consumed by thick jungle of the kind that cannot be walked through—a murk of vines, mud and water moccasins that as of early April 2016 had been flooded by the Yellow River, the same waterway that used to rise to ankle-height inside the McTear house when Houston and his siblings were kids. Some of the homes that stood next to the McTear home are still marked by stray boards or a concrete corner of foundation, but the site where the former World’s Fastest Man grew up looks as if nothing had ever been there at all.

Gail Devers saw the house in 2005, when the three-time Olympic gold medalist paid McTear a visit and walked with him along the train tracks that ran parallel to the house’s front door. “I wouldn’t even call it a house,” Devers said recently. “It was more like a shack ... I walked along the train tracks with him, where he used to race that train all the time. He made me feel like I was reliving it with him.

“Is the mill still there?” she asks.

If the mill weren’t there, if its exposed wooden frame weren’t still poking at the sky like a brontosaurus skeleton—and if not for Devers and a handful of other witnesses—one might suspect the Houston McTear story of being made up. At least its early chapters.

“Shoot, Uncle Willie was the fast one,” George McTear says, standing outside the modest, one-story brick home that Muhammad Ali bought for the McTear family in 1976. George, 60, is the eldest of the eight McTear kids—older than Houston by one year—and was a champion high school sprinter himself. “Uncle Willie was 40 years older than us,” he says. “Still outran us.”

“Uncle Henry was fast, too,” says Charles McTear, Houston’s younger brother by five years.

“Uncle Henry was so fast he’d lose track of his feet,” says George. “He’d get going too fast, then he’d tumble and down he’d go.”

“That horn would blow at the mill,” says Charles, “and that was the thing: We’d meet them at the mill at four o’clock and race to Uncle Willie’s house.” To the naked eye, it’s about a 70-yard sprint. “And if we gave him a good race he might give us a taste of that moonshine.”

Uncle Henry, now a wiry 68, lives just down the road in Crestview, having replaced footraces against his nephews with drag races at a nearby track, starring the fleet of souped-up classics that he restores himself. If the money’s right, Henry will unleash his baby: a purple Nova that came off the assembly line the same year Ali bought Eddie McTear, his brother and Houston’s father, that house. The Nova’s innards-rattling 632 engine is another reminder that, in this family, moving swiftly across the earth is a kind of religion.

So it was that the fastest McTear, Houston Edward—born in 1957, named for his paternal grandfather, and known as Edward until he became famous as a teen—was not built for speed as much as he was born to it. “I have some old pictures of him as a kid,” said Wendy Evans, one of his closest friends growing up. “You can see the definition in his thighs, like a grown man. And then you look down and see that his sneakers are held together with tape.”

“I heard the stories,” says Isaac. “As a kid, he would run everywhere, sometimes out of fear because he had done some mischief or something, and he would listen for the train horn—it was the driver giving him a chance to get ready as the train approached—and then he’d race it. Running was just something he did for fun, until it became clear that he was among the best in the world at it.” Isaac sips, thinks.

“It must have been frightening, really,” he continues. “Most athletes work toward that moment. But in his case someone up there said: This is what you’re good at.” A sip. A shrug. “I mean, how could you not? When you’re that quick and everybody’s making that much fuss, how could you not?”

If you carried that gift and felt the world clamoring for you, would you decline the free flights to New York and London and Los Angeles? Or would you stay in your L.A., what the Florida panhandle calls Lower Alabama? Would you have stayed in a county (Okaloosa) where voters supported George Wallace won more than 60% of the vote in his presidential campaigns of 1972 and ’76? Where, in ’78, according to James Button’s book, Blacks and Social Change, 40 to 50 Klansmen marched fully robed on the Crestview town square, after which letters to the local paper “applauded the Klan and what it was doing to protect the rights of whites”?

Eighteen-year-old Houston McTear, highly attuned to the racism around him, according to his later writings, couldn’t leave fast enough. First was a tour of a dozen or so amateur meets in the U.S. (funded by the Okaloosa County school system), then came a more extensive tour of the globe that lasted into his 20s.

Caroline Willoughby, the 74-year-old widow of coach Will Willoughby, is sitting on the plush carpet in her Crestview home surrounded by yellowed press clippings that show McTear winning more than his share of those early domestic races. “Houston couldn’t read at the time,” she recalls with some discomfort. “But he started carrying a paperback with him that summer and he would put his nose in it on the plane, to make it look like he was reading.” At a stop in Texas, McTear surprised Mrs. Willoughby, who joined her husband on these trips, with a small stuffed giraffe. “He said, ‘For your young ‘uns, for when you get home.’”

“I remember warming up before the [100-yard] final in Atlanta [on June 7, 1975],” recalls Harvey Glance, who was himself 18 at the time and would become McTear’s fiercest rival (and later, a three-time Olympian). “I was real anxious to see this guy everyone was talking about. I was taking practice starts and getting loose, [when] we were called to the starting line for introductions. The official goes down the line: ‘Robinson. Smith. Glance.’ When he said ‘McTear,’ everybody turns to this guy sitting up in the stands smoking a cigarette with his jeans and track shoes on. I looked up and said, You gotta be kidding me. He stepped down on the track, pulled his jeans off and ran a 9.2.” A hair slower than his record 9.0.

“So when I tell you that I witnessed with my own eyes the lack of discipline and lack of training—that was just one incident that defined how talented this guy was ... Never took one stride down the track, not one practice start, and ran 9.2.”

Big Finish: Usain Bolt chasing three more golds in his final Olympics

Later during that summer of ‘75, Tom Murray of Sport magazine watched McTear eat a Big Mac, a vanilla shake and two candy bars in his hotel room, then a couple of hours later, in front of 18,000 fans inside Madison Square Garden, cover 60 yards in 5.9 seconds, “destroying,” as Murray put it, a field of NCAA and AAU champions. It wouldn’t have been as surprising in, say, the 800 meters, or any longer race. But a male teenager had never dominated the sprint scene to this extent, and with the exception of Usain Bolt, hasn’t done so since.

McTear put Baker in his rear-view mirror for good about two weeks before his high school graduation, having been beckoned to California by a wealthy businessman named Phil Fairchild, who promised to underwrite McTear’s training for the 1976 Olympics. McTear would later claim Fairchild was “a rich gambler who owned race horses. And he treated me like just another race horse. If I didn’t win, he came down on me hard.” McTear bolted that scene, but not before he made the Olympic team at the trials in Eugene—the first high schooler to do so since ’68.

As Glance remembers it, his rival began limping right after he crossed the finish line in the 100-meter final at the trials (in second place, behind Glance). Others remember McTear’s hamstring injury occurring while he was practicing baton passes. Either way, the Games were a month hence and McTear couldn’t even jog.

“He came home,” his younger brother Charles remembers. “I guess it bothered him so much that he came home. I remember we were sitting there in the living room watching the opening ceremony, and when the U.S. team came in he was like ...”—Charles leans forward and lowers his face so that his shoulder blades are his tallest point—“‘I was supposed to march in with these guys.’”

“I [had] told him to come [to Montreal] and help me with the practices, that he would have all the rights any other athlete would and he would get treatment for his injury,” U.S. coach LeRoy Walker told a Fort Lauderdale newspaper in 1988. “But this Smith guy kept pulling at him.”

*****

Empire of Deceit, a 1985 book about Harold Smith that was co-authored by the prosecutor who brought him down, paints its protagonist as a collegiate track man turned D.C. hustler named Ross Fields, who at age 32 swindled his way across the country, leaving a trail of bad checks and enemies in his wake. When Fields reached California in 1975 (the year McTear ran his record 9-flat), Fields changed his name to the one under which he would testify six years later, before a grand jury that wanted to know how he had orchestrated the largest bank embezzlement in U.S. history.

“I was reading an article one day here in Los Angeles about a kid by the name of Houston McTear,” Smith testified. “... my wife and I agreed not to turn our backs on this kid.” Smith then somehow gained an audience with Ali, he explained, as the Champ was returning from Tokyo. “Ali [looked] through the magazine [and] said, ‘They live in a house like this, and he’s the fastest man alive and has the chance of winning three gold medals? This is just a shame.’ [Ali] gave me a check for $35,000. He said, ‘I want you to go down there and get him out of that shack. Get him some clothes and some furniture.’ I did. We put him in a four-bedroom brick house.’”

Houston McTear wrote years later that when Harold Smith first showed up in Baker, his 19-year-old mind wondered, “What does he want, what does he have in mind?”

As the authors of Empire explained it: “McTear was [Smith’s] entree into the legitimate sports world ... McTear would bring Smith notoriety. He would bring him Muhammad Ali. And Ali would give Smith the world.”

*****

The house that the world’s most famous man bought its fastest man 40 years ago played host on a Monday afternoon this past April to several of Houston McTear’s relatives, who grilled homemade sausage and sipped beer in the yard. It was mere coincidence, they said, that the fire had been started using old Sports Illustrated issues from the ’70s that they had no use for anymore, their bold color ads—Don’t ask me why I smoke; ask me why I smoke Winston—curling and blackening in the coals.

Charles, Houston’s younger brother, lived with him in Los Angeles during the times when Houston had a place to live in Los Angeles, and now he is recalling the glorious championship fights Harold Smith used to promote, featuring such stars as Thomas Hearns and Aaron Pryor. Harold would rent out an entire floor of the host city’s swankiest hotel, Charles says, and he’d make sure that booze, drugs, and the young women who carried cards around the ring between rounds (Smith claimed he invented the practice) were available in abundance.

“When I came by in the morning,” Houston recounted in a 2005 email to Randy Vennewitz and Andrew Pilger, Los Angeles producers who have since written a script titled, 9 Seconds, “there were traces of coke and alcohol and women—blond, red, black, brown, Asian, name it.” One of the ring girls told McTear that Smith had forbidden them from even speaking to the cornerstone of the Ali Track Club, who seemed to break his own 60-meter world record every time he touched a track. McTear’s email continued:

“I never know to mutch about harald finances... Hrald told me all the time, this is your ticket to retirment and a business futur … just kep on training, running fast and you have it made. ... [I wanted to] learn how to read and write proprely so I didnt have to be so depndent on Harald. I could read but not to fast and some of the words was difficult to understand. Specially in some of the contracts … When he showed off and had people to meet me, it was always time for me to leave… okay Houston, time for me to talk business and dollars and you back to training …”

• SI Vault: McTear’s 1978 SI cover—“He Sure Goes Like Sixty in the 60”

By the time McTear appeared on the cover of SI on March 6, 1978, in an issue that lauded his fourth world record in eight weeks, Harold Smith had walked into a Wells Fargo bank in L.A. and presented a suspicious check to a banker named Sammie Marshall, which Marshall declined to cash. On Smith’s second visit to the bank, however, as described in Empire of Deceit:

“[Smith] was accompanied by a muscular young black man who walked in short, almost dancelike steps ... ‘I’d like you to meet Houston McTear, the fastest human alive,’ [Smith said to Marshall] … McTear nodded and awkwardly took the banker’s hand. He seemed unsure of himself and painfully shy… ‘Houston’s my main man,’ Smith put in. ‘He’s gonna smash all the records there’s to smash. The Champ’s behind him, too.’

Based on this celebrity-rich monologue, Smith’s out-of-state check got cashed. It would be the first trickle in a three-year embezzlement scheme that funneled more than $21 million from Wells Fargo’s vaults to the accounts of Smith’s new company, Muhammad Ali Professional Sports.” (Ali himself was never implicated in any aspect of Smith’s enterprise.)

McTear—the teenager whose celebrity Smith had used to unlock those vaults—was remembered by Rene Felton Besozzi, the former U.S. hurdler, as an athlete who was humbling to watch up close. “I consider him the fastest sprinter ever over the first 20 or 30 meters,” she said recently from her home in Italy. “When he ran, you just stood there in awe. But when he shook your hand, there was such gentleness.”

Bolt, Farah among men’s track and field stars set to take Rio stage

“Young country boy, sweet as he could be,” says Steve Williams, the brash New Yorker who throughout the 1970s ranked among the top 100-meter men in the world. “Here’s one of my favorite McTear stories,” Williams continues. “Nice, France, 1975 … Topless women shoulder to shoulder on the Cote d’Azur. Mac couldn’t even walk he was so busy looking around! … We stayed in a nice hotel with a sauna, and of course the women were naked in the sauna, too. McTear spent so much time in the sauna he bombed in his race the next day. Massive dehydration.”

Former British sprinter Andrea Lynch, a close friend of McTear’s during his ascent, recalls that “when we went to the beach [in Los Angeles], Houston would wear his clothes the whole time. Jeans, T-shirt. Fully dressed.”

“His favorite phrase,” Lynch recalls in a vain attempt to sound Southern, “was, ‘It just bees that way sometimes.’”

In contrast to Lower Alabama, Los Angeles in the late ’70s was a place where anything was possible. In the punk scene, the porn scene; in the cavernous sound stages of Hollywood. The Lakers drafted a player named Magic. The fastest man in the world trained at the Muhammad Ali Track Club in Santa Monica.

Harvey Glance remembers the 60-meter final at the 1978 Muhammad Ali Invitational more vividly than all of his other matchups with McTear. The sprinters assembled inside Long Beach Arena that day were the epitome of world-class. “Someone showed me a YouTube video of it the other day,” Glance says, “and I realized that seven of the eight finalists had a world record or an Olympic medal.”

NBC’s telecast of the event featured a 10-second self-introduction by each sprinter, who gave his name, his lane number, and his goal for the race. McTear, never one to break a sweat before running, was bleeding clear beads. His bloodshot eyes half-shut, he gave viewers the wrong lane assignment then stated his goal as: “I hope to do good.”

“We had been in my house in Long Beach shortly before that drinking beer and smoking weed,” his best friend from Florida, Alfarri (Bill) Jones, recalled recently. And yet the race was over after 20 meters.

Had it been a 100 instead of a 60, ’76 Olympian Steve Riddick might have caught McTear, but as it stood, the Floridian flashed across the line in 6.54 seconds, besting the world record of 6.57 that had been held a heartbeat earlier by a German. Afterward, McTear was asked why he seemed to perform so well when Ali was present. A jagged grin crawled across McTear’s 20-year-old face. “That’s my maaan,” he explained.

“His start was so good that it could ruin your whole strategy,” Glance recalls. “I used to tell my coach: The only way I can prepare for Houston is to race him. You can’t study something like that. It was like Mike Tyson in his prime. Everybody thinks they’re O.K., until they take that first lick.”

The world-record that McTear set that day would stand for eight years, until it was broken by Ben Johnson in 1986. (Johnson’s mark would be annulled due to his steroid use). Actually, McTear broke his own record with a physics-defying 6.38 at the ’80 Ali Invitational, but that mark would be invalidated due to the rarely cited “questionable timing.” Glance, whose time that day (6.41) also came in under McTear’s record, cites a simpler reason that their times weren’t deemed official: “They didn’t believe it was possible for two guys to run that fast.”

Asked where McTear ranks, all-time, in terms of natural speed, Glance’s pause is shorter than the one between the starting gun and his rival’s first step. “Clearly number one,” says the veteran of three Olympics and 20 years as an SEC head coach. “I’ve seen some natural athletes. Some didn’t like to train and they’d still go out and have success, but none of those guys were world record holders. That’s what separates him. He was the most gifted sprinter I’ve ever seen.”

Hilton Nicholson, McTear’s personal coach during the Ali days, concurs that track and field has never seen a more breathtaking natural athlete. “It was purely God given… Raw and beautiful. I had never seen anything like it.”

“Gone,” is Steve Williams’ one-word summation of McTear’s gift. “You blink your eyes and the guy’s standing up and you’re looking at his butt.”

McTear continued to disobey physical and pharmacological science at Madison Square Garden in ’78, when he broke the world record over 60 yards with a tidy 6.11. Afterward, he boasted: “I want to go outdoors. I wish the 1980 Olympics were next week.”

*****

One of the many edges of the Anything-can-happen-in-L.A. sword was Houston McTear getting married. The bride was a tender-hearted young Brit named Janette (Jeannnie) Gow, who had been introduced to McTear by British sprinter Andrea Lynch while on holiday in L.A. “After about two weeks,” McTear told Jet magazine, “I knew she was the one.”

Not a soul in Baker knew about the nuptials (which Jet reported had taken place in “an ultra private civil ceremony in a Los Angeles courthouse”) until that issue of Jet made it to town, its 15th page showing Baker’s favorite son carrying his white bride across the threshold. When Houston called his stunned mother, Margree, she demanded to see the marriage license as proof.

“Both 21,” the Jet story noted ominously, “the newlyweds are living off money McTear gets from his manager Harold Smith …”

McTear wrote years later that “Harold was upset” about his star sprinter’s surprise wedding. For most of their four-year marriage, due in large part to his escalating drug habit, McTear treated Jeannie like the distraction that Harold Smith told him she was.

“If you’d called me 25–30 years ago,” the former Janette McTear said earlier this summer, on the phone from her home in England, “I might answer these questions a bit differently, but Houston was a good soul. He meant well … I certainly don’t wish to speak ill of him.”

Says Alfarri Jones, who knew McTear throughout his “L.A.” period and his L.A. period, “Houston was the type of guy—there was no way he could bring any harm to anyone but himself. I think the most harm he did to anyone was to Jeannie. Leaving her and Isaac alone. He just wanted to be wild.”

On this failed relationship, McTear was reticent in his emails to the Hollywood producers: “dont want to say to mutch or get to deep.”

McTear made it to the finals of the 1980 Olympic trials, but finished seventh. According to Glance, “He wasn’t the same Houston. His start was not as explosive. He would throw guys off in the first 40 to 50 meters of a race where they’d break down technically and just fall apart … [but] around ’80, ’81, he wasn’t that imposing threat in the blocks anymore.”

Even before those trials, as the U.S. boycott of the Games loomed, McTear entertained the idea of an NFL career. The greatest among McTear’s eye-popping athletic stats might still be the 14.4 yards he averaged (1,380 yards on 90 rushes) as a high school junior. Tom Landry apparently saw those numbers, because Jones fielded a call from the Cowboys head coach one day while hanging out in Houston’s hotel room in New York.

“I think I can play,” McTear told Jet in spring 1980. “… I know I can take the punishment. You just have to know how to fall.”

*****

[youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ffyobqtPI8]

“I told you about us smoking and drinking before he set that record?” says Jones. “It all changed up when he [began using] crack. That just set a whole new precedent … You had doctors and lawyers who would do a few snorts [of powder], but that crack cocaine … That was a bad time in his life, man.”

McTear might have beaten his early-stage addiction and gone on to great things—maybe the ’84 Olympics—were it not for a triumvirate of events that struck in 1980. The first of these three, the only one that McTear brought upon himself, came when Jeannie moved back to England with the couple’s three-year-old son, Isaac, and his unborn daughter, who would be named Autumn.

lIsaac grew up with him a little bit in America,” recalls 34-year-old Autumn McTear, born and raised in London and now a 31-year-old mother of two, “but I hardly saw him until I was about 17 ... My mum didn’t want me growing up around substance abuse. Didn’t want Isaac around it.”

Jimmy Carter’s announcement that the U.S. would not compete at the 1980 Olympics was the second mortar shell. “I remember he was near tears and for the first time I heard a little quiver in his voice,” says Jones. “I never knew Houston to cry. He didn’t boo-hoo or nothing, but he was on that verge.”

McTear suffered the third blow nine months later, in January 1981, when FBI agents approached a Wells Fargo banker named Ben Lewis and started asking him questions about his good friend Harold Smith. Within 17 months, the former Ross Fields was convicted of 31 charges related to his grand-scale bank embezzlement and was sentenced to 10 years in prison. (Smith, now living in Dubai, politely—and somewhat eccentrically—declined a recent interview request via email, writing: “i am going to follow my reliable Instinct and the advice of a few others by simply refusing your request at this time on this matter. You have a bless day …”)

What to watch and when: Must-watch events each day of Rio Olympics

As for Smith’s stable of athletes, when the gavel dropped on his conviction, they “packed their bags and returned home,” wrote the Deceit authors. “... The Champ was no longer behind them. The dream was over.”

“Suddenly I was broker than when I left florida,” McTear wrote in a 2005 email.

What footspeed he had left came in handy when McTear was paid a visit during the federal investigation that sent Smith to prison. Empire of Deceit recounts a blind knock-and-notice that an FBI agent named Taulbee made to an address in Santa Monica, along with a second agent “who happened to be the best runner in the FBI’s Los Angeles office.” They knocked on the door, got no answer, then heard someone jump from a window and dart into an alley. The ensuing footchase was fruitless.

“‘I don’t know who that guy is,’ huffed the agent, ‘but he can move. I didn’t have a chance.’ Interviewing the next-door neighbor, Taulbee asked who lived at the address. ‘Why, Houston McTear lives there. The world’s fastest human.’”

“I just went deeper into destruction,” McTear wrote in his emails to the filmmakers. “I was suddenly a lonely man, with other lonely associates, no friends … I got deeper into my addiction. It took it all. I was skin and bones. ‘Homeless.’ … I could have went home [but] I was too ashamed about it all. PRIDE.”

Instead of Florida, McTear “went to a source that gave him relief,” says Jones. “So he could just forget all that stuff. I think he just checked out.”

When the last of his money was gone, and that didn’t take long due to his $300-a-week cocaine habit, McTear slept on the tennis courts at the Pritikin Longevity Center, or under the Santa Monica Pier. He crashed with an old flame named Sue (the mother of his third child, Micheline). A friend bought him a few nights at The Flamingo, the area’s least discerning motel. He knew he could depend on sandwiches at 11 a.m. at Clare Foundation, which is still there, still serving the homeless.

“Nobody realized Houston was homeless,” says Williams, McTear’s sprinting rival and travel partner. “Track people live such a far-flung life, all over the world, and we come and go so quickly … sometimes we lose track of one another.”

Houston’s younger brother Charles was still in L.A. He had married and was raising a son and working as a manager at a Santa Monica McDonald’s. “I helped him out numerous times,” Charles recalls, “but when he was at his worst, you have to understand, there was no way he could stay at our house with our child there ... People asked me all the time to get Houston straightened out, but he was five years older than me. I couldn’t tell him nothing.”

Accounts vary as to how long McTear lived among Santa Monica’s homeless. Some say five years, some say two. The most reliable estimate is three years—a span of about 1,100 days somewhere between the Olympic years of 1984 and 1988.

McTear’s only companion was a stray chihuahua that he named Speedy. They were inseparable, until Speedy “got stolen on the beach while I was sleeping ... I loved that dog and looked for him every day for a year.” That search would prove as futile as McTear’s search for consistent shelter.

By his own account, McTear slept most nights at Cactus Park, which today looks just as it did in the ’80s—a weathered wooden pagoda perched on an acre of hilly grass next to the ocean. The only difference is that the cacti are gone. The plants that once thrived there—the kind with large, flat, rigid leaves—provided a low-lying apartment complex for those with no other roof.

McTear showed Cactus Park to Gail Devers in 2005, about 17 years after he had moved on from there. “We spent a lot of time just standing there looking at the water,” Devers recalled this spring. “He told me that in order to get a bed [at a shelter] he had to be somewhere at a specific time, and sometimes it didn’t work out. So outside became his house ... We talked about how people spend all this money so they can live by the ocean and have this picturesque view, and he said, ‘Well, I had it.’ That’s the kind of person he was. He didn’t dwell on the negative for too long.”

*****

“My mom was a nurse,” says Ed Francis, son of the late Arlene Francis and brother of Russ Francis, who starred as an NFL tight end during the 1970s and ’80s. “She was experienced with drug abuse … and one day she was sitting at that pagoda after work, and [Houston] sat down next to her and struck up a conversation. They met there several more times before she had an inkling of what his athletic background was. Someone else told her. Houston didn’t.”

Recently divorced, Arlene Francis was wary of McTear at first, but soon she introduced him to Ed, who was 25 at the time. “He had pretty much beaten [his cocaine addiction] by the time I met him,” Ed recalls. “A couple times I had to track him down on the street—‘Yeah, he’s in number 6 at the Flamingo.’ He didn’t want me to find him like that but on both occasions he took a few seconds to grab a shirt and he got in the car with me.

“We started doing some hill training. Nothing on the track. Right next to Cactus Park was a hill—my mom called it Houston’s Hill. That’s where we did most of our running.”

McTear had attempted comebacks before. (How could you not?) His most recent one had ended with a cocaine rehab stint in ’86, which was followed by another backslide and an arrest for possession. Arlene Francis paid McTear’s $2,500 bail on that occasion, then stood by him during his guilty plea and 29-day jail sentence. She invited McTear to move in with her and Ed.

*****

Like the starcrossed progeny of the Montagues and Capulets, Linda Haglund and Houston McTear had more in common than one might have suspected at first glance. Their most glaring compatibility was that they had been among the fastest humans in the world during the 1970s. Haglund, nicknamed the Gazelle in her native Sweden, grew up running barefoot through the forests of Tyresö, the wooded Stockholm suburb her family called home. Her frequent stops to eat blueberries or spy on deer turned her into a sprinter instead of a distance runner.

The lithe, pigtail-wearing teenager was a natural athlete in every sense. Like McTear, Haglund served as her own coach until she was 18, after which she met with a coach only once a month. A local paper captured perfectly the surprising, giddy success of Haglund’s early sprinting career: ingen i Sverige då visste hur man tog sig an en supersnabb tonårstjej.

“Nobody in Sweden knew what to do with a super-fast teenage girl.”

Haglund still holds the Swedish records in the 50, 60, 100 and 200 meters. She beat the reigning sprint queen Evelyn Ashford in ‘81. She had even crossed paths with Houston during their heyday, proving herself every bit as elusive as the introvert she would later marry.

McTear gave her a lift from LAX in ’79 so she could compete at that year’s Ali Invitational. “I was going to pick her up next day to show [her] around,” he recalled years later, “[but] she was gone.”

It was 1989 now, and the decade since that encounter had been long years for them both.

Linda’s crucible, like McTear’s, began in 1981, before which she had been Sweden’s sweetheart, a three-time Olympian who missed a 100-meter medal in Moscow by the skin of an East German’s singlet. In July ’81, according to Linda, she received a bottle of what she was told were Vitamin B pills from her coach under instructions to take one a day for the three weeks preceding the Swedish championships. Haglund believed in natural food, not pills, so she ignored these orders and only took two of the tablets, on a whim, because she felt a cold coming on.

Sweden, one of the first countries to administer out-of-competition PED tests, was ahead of its time with regard to drug testing. Linda knew this, which made her positive test after the ’81 Swedish championships all the more surprising. She was banned for 18 months by the IAAF, despite having been absolved by the Swedish track federation—an acquittal based on a hard-won letter from her Finnish coach, Pertti Helin, which clarified his role in her positive test.

Haglund’s comeback effort in 1984 was both brief and passionless. “Her heart had been broken,” says Ulf Ekelund, head of Sweden’s track federation at the time, sitting in a Stockholm lounge this summer. “People looked at her differently. It was the heaviest burden she carried in her life, and she carried it until the end.”

“She worked as a teacher later in life,” says Torbjorn Ring, editor of Haglund’s book Lindas Resa [Linda’s Journey], “and on occasion students harassed her [about her doping case].

“She was a sensitive person,” Ring adds, standing next to the modest track where Haglund ran her first races as a girl. “Very sensitive. But not frail.”

In 1989 Haglund was working as a track coach at Santa Monica College. “I was married at the time,” she recalled in an email to the 9 Seconds filmmakers (which included an apology for her “Swenglish”), “but I was separated in mind and body.

“While preparing athletes for training … a guy named Ed Francis approached me … he mention the name. Houston McTear … I told Ed I was too busy to talk but tell to Houston hello from a old track friend and to tell him to come down for a chat…

“3 day’s later [McTear] showed up … He smiled and waved hello. He looked out of shaped and seemed hurt. I could see it in his eyes – the pain and sadness of life. (WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH.)”

McTear recalled in a separate email:

“When I saw her my heart started to beat … I could feel this was a new beginning after 8 years struggle I could feel it in my bones! My life was going to change …”

Haglund: “Two day’s later he showed up on time, wearing a training overall from the 70s … [He helped] me train the athletes on that day and every day afterward … We biked, ate, and walked on the beach. I cut his hair [and] helped him get a new wardrobe … My friend Michelle said she could have fried eggs with [the] heat between Houston and I. Thereafter, he trained every day, and we started to talk about Sweden and track meets in Europe.

“When Houston met Linda,” Charles McTear recalls, “he came to me and said, ‘Bro, I need to come and stay with you, I’m gonna clean myself up.’ I said, You’re not gonna bring that s--- up in my house, man. But he kept his word, cleaned himself up. Stayed clean. He was with us for a couple of months.”

Felton Besozzi, Haglund’s assistant coach at SMC, remembers that a few days after Linda met Houston, “she and her husband fought and broke up. She said, ‘I’m going back to Sweden and taking Houston with me.’ They literally packed up and left.”

“After two months training,” Linda reported via email, “he ran 10.52 [100 m] in his first meet in Sweden”—a borderline national-class time. This from a 32-year-old who had been sleeping wherever he fell for months. For years.

Back then, at his lowest point, “Houston said that the only way he’d ever run again was if somebody was trying to hurt him,” Arlene Francis told the Los Angeles Times in ’88. Now McTear was running 6.68 over 60 meters to become Sweden’s national indoor champion at that distance.

Linda began preparing her recently homeless boyfriend for the Globen Games in Stockholm, but Globen officials, she wrote, “did not want Houston in the meet. … I told them why not let him compete, and only if he wins that he should be paid $20,000. They laughed sarcastically and said no problem because he will not pass the trials since we have three of the world’s best in the meet. “

The 60-meter field at the 1991 Globen Games included Chidi Imoh, who would win 60-meter bronze at the indoor world championships later that season, and reigning 200-meter world champ Calvin Smith. McTear beat both younger sprinters, and everyone else who made the final, in a time—6.65—that was just .11 shy of the world record he’d set 13 years earlier (while stoned out of his mind). It was .26 off today’s world record, which was set by Maurice Greene when Greene was 23.

No one is sure why, or even when, McTear stopped running. His insistence on trying to make the 1992 U.S. Olympic team—instead of Sweden’s—did nothing to extend his comeback. A Canadian paper reported that “a change in Swedish tax laws pushed [McTear and Haglund] back to the U.S.” Perhaps residing in a park for the better part of three years had finally begun exacting a toll. Whatever his reasons, a question had been raised during his unprecedented return to the track:

Is Houston McTear the greatest natural sprinter ever?

“Just to go out there and compete, with all his body had gone through?” says Glance. “Who knows what this guy could have done if he had worked at it?”

“If he hadn’t gone through the drugs and the homelessness and all the things he went through,” says Devers, “or if he had met Linda and made his comeback earlier than age 34 … my God, what would the records be?”

*****

In the side yard of the Ali house in Crestview, Houston’s brother Fred is expressing the family’s impression of Linda when she and Houston moved to Florida together in the early ’90s. “She act like she ain’t never met no stranger,” Fred says, surrounded by siblings and wearing a white tank top and a couple of gold teeth. “Linda fit right into the plan. You tell that girl a lie, she’d tell you one right back. She was like, ‘This is my family now.’”

Linda’s skin quickly bronzed to a deep brown, such that when she walked with Fred and another McTear to a local dealership to buy a used car, the threesome was not heartily welcomed. Racism wasn’t the issue. According to Linda, the car dealers later informed a neighbor that a Cuban woman had come in with the McTear boys, speaking in tongues and trying to pull some kind of car swindle.

Linda ended up selling cars at that same Crestview dealership—“the only woman selling with 12 other guys,” wrote the greatest female track and field athlete in Sweden’s history and an Employee-of-the-month at Hub City Ford. “One person said I was like an exotic bird, just passing by …”

Houston worked at a gym in nearby Fort Walton Beach, until his boss got busted for selling steroids, which, irony of ironies, might have been the only kind of drug McTear never took.

Death to the Olympics: Why the Games should have been moved from Rio

“When they moved back to Sweden,” Bill Jones says, “that’s when we reconnected. He told me, ‘I’m teaching boys track at the school where Linda works … I get to see my daughter. I get to see my daughter’s kids. I get to see Isaac and his children.’

“I’d get on the phone with Linda and she’d say, ‘Bill, he is doing so good.’”

One of the few challenges Houston and Linda faced in Sweden was a familiar one to McTear. “She mentioned a racial issue a couple of times,” said Isaac, who noted the influx of darker-skinned immigrants into Scandinavia at that time, and the fact that Haglund was still the nation’s sweetheart in many Swedes’ eyes. “From time to time [McTear] would get a hard time if he was in the car. The police would see that it was Linda’s husband and pull him over. It was something that they both mentioned.”

McTear’s name does not appear anywhere in Haglund’s 2013 autobiography, which doesn’t even mention that she was married. “She wanted to protect him,” says Ring, her editor and friend. Her book, she had decided, was not the place to tell stories like the one in which McTear found himself surrounded by angry right-wingers on a Stockholm street. That incident resulted in what Isaac called it “a bit of an altercation. He was set upon, they gave him a bit of a beating—but Linda and my dad never gave any details beyond that. They were quiet people.”

In an email to Vennewitz and Pilger, the L.A. movie producers, Linda conceded: “I’m the one who goes to functions and Houston is living very privately in Sweden … we have meet some racism, it has grown over here the last 5 years.”

Houston and Linda settled in an apartment in a scruffy Stockholm suburb called Haninge, where the playgrounds, on a recent visit, were populated by African and Middle Eastern immigrants and their children. From that home base, remembers Isaac, “Linda put a lot of effort into bringing my dad back together with his kids and his grandchildren—trying to patch that up. It was his opportunity to make up for what he didn’t do before.”

“His grandkids loved him,” says Autumn, “especially Justice”—her 13-year-old son. “Justice wanted to go live with him in Sweden,” she laughs. “Wanted to ditch mummy.”

In the summer of 2015, Isaac felt a sudden inspiration to fly to Stockholm with his then-8-year-old daughter, Aaliyah, so she could spend time with her 58-year-old granddad.

“When I first saw him, I was shocked,” Isaac recounts. “He looked 20 years older. For me, my dad was always this young, strong guy. For the first time ever, I saw someone who wasn’t well. But he never told us what it was.

“The last thing we ever done together was go watch an athletics meet in Sweden,” Isaac continues. “Linda hooked up some tickets for us ... I can’t think of anything I would rather have done with him. Sit there, criticize and comment, y’know?”

The Greatest of All Time ended up outliving his friend and protégé, the World’s Fastest Man, by seven months. McTear died on Oct. 31, 2015, of advanced lung cancer, which he had refused to disclose to anyone but Linda.

Two weeks after McTear’s death, Linda found herself physically unable to get out of bed. She was taken by ambulance to a hospital and placed immediately in ICU, where doctors discovered a cancer so widespread that they never named a specific body part. “The metastasis defeated her breathing and circulation,” her brother Jimmy told reporters. She died five days after she was admitted, nudged toward her end, her friends insist, by the loss of her soul mate.

“I look at Linda as the guardian angel,” says Devers. “She saved his life. And if you knew them, you knew that she wouldn’t have made it by herself after Houston left. A part of her was gone.”

The European press advanced rumors that Linda and her husband had been estranged and were living separately at the end. Linda herself told Expressen in 2012: “I live alone with my dog. I’m not married. But I do not want to talk about my private life.” It was another layer of protection, her friends say, for a man she felt had endured enough human harshness.

Isaac, who was on the phone with Linda throughout his dad’s final days, insists, “No one could have taken care of him better than she took care of him at the end. There is nothing she wouldn’t have done to look after him. So to hear that they were apart, it’s amusing to me, because they were very much together. If anything, his illness brought them closer.”

Their best friends say that Houston and Linda were together until the very end, their starkly different faces filling the screen when chatting with loved ones via Skype. These recollections left everyone puzzled, though, when Linda failed to attend Houston’s memorial in Florida—which was held at Beulah #1 Missionary Baptist Church, built by Houston’s dad decades earlier out of the pine forest that surrounded it. Only when Linda died did her reason for skipping the service became clear. The Gazelle could barely move around her apartment, much less fly across the Atlantic.

In February 2016, Houston Isaac McTear was born in London. Isaac’s son will never experience his granddad firsthand. He’ll have to be satisfied with hearing about him, with absorbing the stories of his legend, stories that are fading with time, dissolving like the missing McTear shack in Florida. (“All those years,” Charles McTear says, looking at what used to be his boyhood home, “if you tried to pick any of it up it’d probably fall apart.”) So it was especially important that McTear’s oldest granddaughter be given a few, last, tangible memories of him last summer during her visit to Stockholm.

“That’s what that trip was really all about,” Isaac says, finishing his tea. “He had become like a mythical character to her. Like he didn’t really exist in person. He’s like that to a lot of people, I think.”