Usain Bolt reigns again in closing act of his individual Olympic career

RIO DE JANEIRO — This is what you should remember: That a cool, misty rain was falling from the night sky over the Olympic Stadium, landing on the blue running track and giving it the look of an icy sidewalk somewhere in the northern winter. That it was a Thursday night and the stadium was nearly full, but not entirely full, because these were the troubled Rio Olympic Games and even when the moment was historic, the setting was often vaguely imperfect. That the runners emerged at 35 minutes past 10 p.m., from the tunnel at one end of the stadium, and then jogged clockwise to the starting line for the half lap of the 200-meter final.

That when the cameras found him, he swayed in a Samba dance and spread his arms wide as if to embrace the moment. That he furrowed his brow in mock seriousness and then raised his eyebrows to let the world in on his joke. Because he has always made our world part of his world. That he folded himself into a starting block in lane six and as evermore, the act looked just a little bit awkward for a man so big, 6' 5" with the arms and legs of an even taller man.

That the last individual race of Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt’s Olympic career began like so many other of his 200-meter races, which a searing curve that left him with a huge lead as he unfurled his stride into the homestretch. That he tried, really tried, to destroy the field and break the world record in the last 100 meters, but his shoulders rose just a little higher and his face tightened into a grimace and for the first time in all these Olympic races, and three days shy of his 30th birthday, he looked a little bit old. He looked like a man whose decision to walk away from a sport in which he has been a world-class sprinter for 14 years is a wise one.

“I wanted to run faster,” said Bolt when the race was finished. “But my legs decided it wasn’t happening. I felt tired and I lost my form in the last part of the race.”

You should remember that despite all of this, Bolt was never really threatened by any of the other seven runners in the race. He crossed the finish in 19.78 seconds, to an adoring roar, chased most closely by 21-year-old Andre deGrasse, the mighty mite Canadian and former USC sprinter who had forced Bolt to work so hard in his semifinal heat the previous night.

“I thought tonight was the night to take him down,” said de Grasse’s coach, Stuart McMillan. But on the line de Grasse was timed in 20.02 seconds, a distant quarter-second behind Bolt. Said McMillan, “Of course a lot of guys have tried to take him down and nobody’s done it.”

And you should remember that you were there. You should see the moment, hold the moment, and stash it away in your soul, because there will probably not be another runner like Bolt in this life. Ryan Crouser, a 23-year-old U.S. shot putter, had won the gold medal in his own event and remained in the well of the stadium to watch Bolt run. He comes from a track family and his knowledge of the sport is so deep that he referenced his affection for East German shot putter Ulf Timmerman, gold medalist in 1988, and whose Olympic record Crouser broke. Crouser had never seen Bolt run live, so he watched.

“Cool to have a gold medal around my neck,” said Crouser, “and see him finish off one of the spectacular careers ever in track and field.”

Ashton Eaton’s second decathlon gold medal truly an Olympic-sized feat

Ashton Eaton, 28, was in the stadium, too, having finished off his second consecutive decathlon gold medal. Four years ago in London, Eaton also secured his gold medal on the same night that Bolt won the 200. “It’s been a pleasure just being in the same era as Usain Bolt in track and field,” said Eaton. “The guy’s last name is Bolt and he’s the fastest man, ever. To be in the pages with him is the best.”

Bolt left the stadium last night with six individual Olympic gold medals, two each in the 100 meters and 200 meters in the 2008, ’12 and ’16 Olympics. No man before had ever done it twice. He holds the world records in the 100 (9.58 seconds) and the 200 meters (19.19 seconds) both set at the 2009 world championships in Berlin. Those records are unlikely to be challenged for many years. His victory on Thursday was the least spectacular of those six individual wins, and by far the slowest of his 200-meter golds. He ran a then-world record 19.30 in 2008 and 19.32 in London. Soon that will fade from any importance.

“The key thing is I won,” said Bolt. “And the only thing that matters is the gold medal.”

Usain Bolt's Olympic finals races, ranked

His performance was the closing act of two days at the Olympic Stadium that were dominated by Americans. After a one-two-three sweep of the women’s 100-meter hurdles closed out a seven-medal (two gold) Wednesday, U.S. athletes roared back Thursday with six more medals, including golds by Crouser, Eaton, Delilah Muhammad in the women’s 400-meter hurdles and, earlier in the day, Kerron Clement in the men’s version of that same event. The U.S. now has nine gold and 25 overall medals in track and field, likely to blow past the 2012 totals of nine and 29 and possibly the non-boycott modern records of 13 golds (Atlanta, 1996) and 30 total medals (Barcelona, 1992).

But the night ended with Bolt, because the night always ends with Bolt. He had easily won the 100 meters on Sunday night in a time of 9.81 seconds, also the slowest of his three 100 victories. But the 200 meters has always been the event closest to Bolt’s heart. It was where he first ran fast, breaking the world junior record with a time of 19.93 seconds in the summer of 2004. He was 17 years old. The underground track and field community was fascinated by watching such a tall, young boy leverage the turn and slingshot into the homestretch. Plus, as Eaton says, there was that name. Usain Bolt. He would stagnate in the event, improving by only .05 seconds in the ensuing three years while fighting his body and his own indifference to truly hard training.

When he broke through in 2008, it was in the 100 meters, in which he twice broke the world record. His stunning gold medal race at the Beijing Olympics, where he ran away from seven other world class sprinters as if they were discus throwers, launched his worldwide celebrity and created the persona of Usain Bolt, speedy cartoon superhero. He ran 9.69 seconds that night and could have run much faster. A year later he lowered the mark to the ridiculous 9.58 seconds. But Bolt holds the 100 meters at arm’s length; he dislikes relying on his start and tires of running from behind.

Usain Bolt provides moment of pleasure for track and field, Olympics with 100m gold

He has dominated the 200 even more than he has owned the 100 meters. He has run under 19.60 seconds nine times; four other men (Yohan Blake, three; Michael Johnson, Tyson Gay and Walter Dix, once each) have done it a combined total of six times. And yet, because of the toll on his long, fragile skeleton, Bolt has run the 200 just 16 times since winning the gold medal in London, and six of those races were preliminary round heats.

But here on Wendesday night, in the semifinals of the 200 meters, Bolt ran a fierce curve and then after slowing to ease across the line, was suddenly chased by deGrasse. The two runners looked at each other and the internet interpreted that as having fun. Bolt wasn’t pleased. “I don’t know why he did that,” said Bolt after the semifinal. “You don’t need to run that fast.”

There was a reason. McMillan thought that a hard run in the semifinal might wear down Bolt. “Our strategy was that Bolt has had some injuries this year,” said McMillan. “He’s not in the greatest shape this year. I told Andre, ‘Push him through the line. You’re younger. Maybe he won’t recover as fast as you do. Bolt doesn’t have the greatest record when he gets challenged.’” (McMillan referenced Bolt’s only major championship “loss,” when he false-started out of the 2011 world championships 100 meters, as he was about to face ascendant Jamaican Yohan Blake).

The tactic worked. And it didn’t work. It’s true that Bolt has not had a perfect year. He ran well into June, but tweaked his low back and left hamstring and withdrew from the Jamaican Olympic Trials on July 1. He missed nearly two weeks of training and raced just once before the Games, a 200 meters in London on July 22. That was his only 200 of the year, before Rio. “It’s been mentally and physically challenging.” Said Bolt. “Just to get over this hump is brilliant.” (Bolt uses words like “brilliant” and “legend” often, in ways that make him seem prideful. He is prideful, but his usage does not fully mirror U.S. usage. He’s not overtly cocky; it’s all a game with him).

U.S.'s Evan Jager clears another barrier in breaking Kenya's distance dominance

In the race, despite his struggles this season, Bolt started spectacularly—his reaction time of .156 seconds was in the middle of the field, good for him—and then torched the curve, per usual. But as the crowd waited for him to pull away in a tour de force in the straightaway, instead he just grinded, holding the field clear. The clock froze the final time of 19.78 (behind de Grasse in third was Christophe Lemaitre of France in 20.12; the only American in the race, LeShawn Merritt, finished sixth). Bolt swatted at the air in obvious displeasure. “I just was not pleased with the time,” Bolt said. But the disappointment faded quickly.

In a post-race interview, he was asked to recall his first Olympics, in 2004, when as a 17-year-old he did not make the 200-meter final. He became somewhat wistful. “All I ever wanted to do was run the 200 meters and win the Olympic gold medal once,” he said. “So to be an eight-time gold medalist is a big deal and pretty shocking. I’m not stressed. This 200 meters is more of a relief.” Friday night he will anchor the Jamaican 4x100-meter relay, chasing medal No. 9.

As to retirement, he said what he has said all along: That his decision is final. “There’s nothing else I can do,” he said.

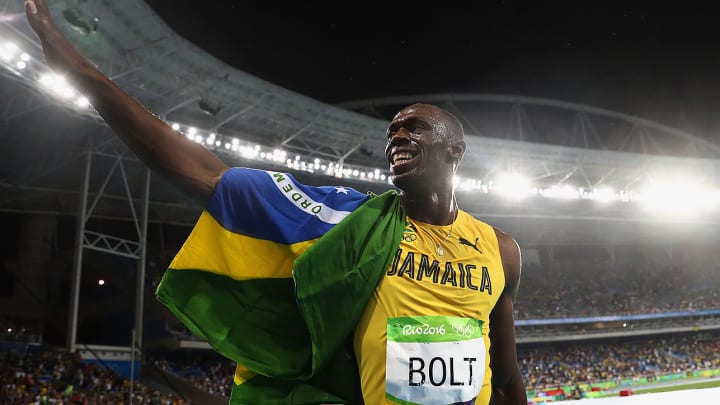

There was one last victory lap to run. He took the Jamaican flag and circled the outside of the running track in what has become a Bolt ritual. His celebrations are as memorable as his races, full of communal spirit, lacking in pretense. He took selfies, he laughed, he went into the stands to visit the Jamaican delegation. Finally he arrived back at the finish line, 13 minutes after the start of his race.

He fell to his knees, bent forward, and planted a kiss on the finish line. “Just saying goodbye,” he said. “This was my last individual event at the Olympics, so I wanted to say goodbye.” He rose from his knees to his full height, turned 90 degrees to his left and performed the famous Bolt pose.

You should remember.