With odds stacked against her, Mallory Weggemann never lost competitive drive

When Mallory Weggemann wheels out to the pool deck, her face remains friendly but mostly expressionless, her ears covered by pink headphones and her eyes staring forward toward her aqueous home. As she prepares to dive in, she forgets about how she got here—her leg weight disappearing following an epidural shot, a shower bench collapsing causing permanent injury to her left arm and the bureaucratic nightmares surrounding her Paralympic classification drift—for a few minutes at least, so she can swim.

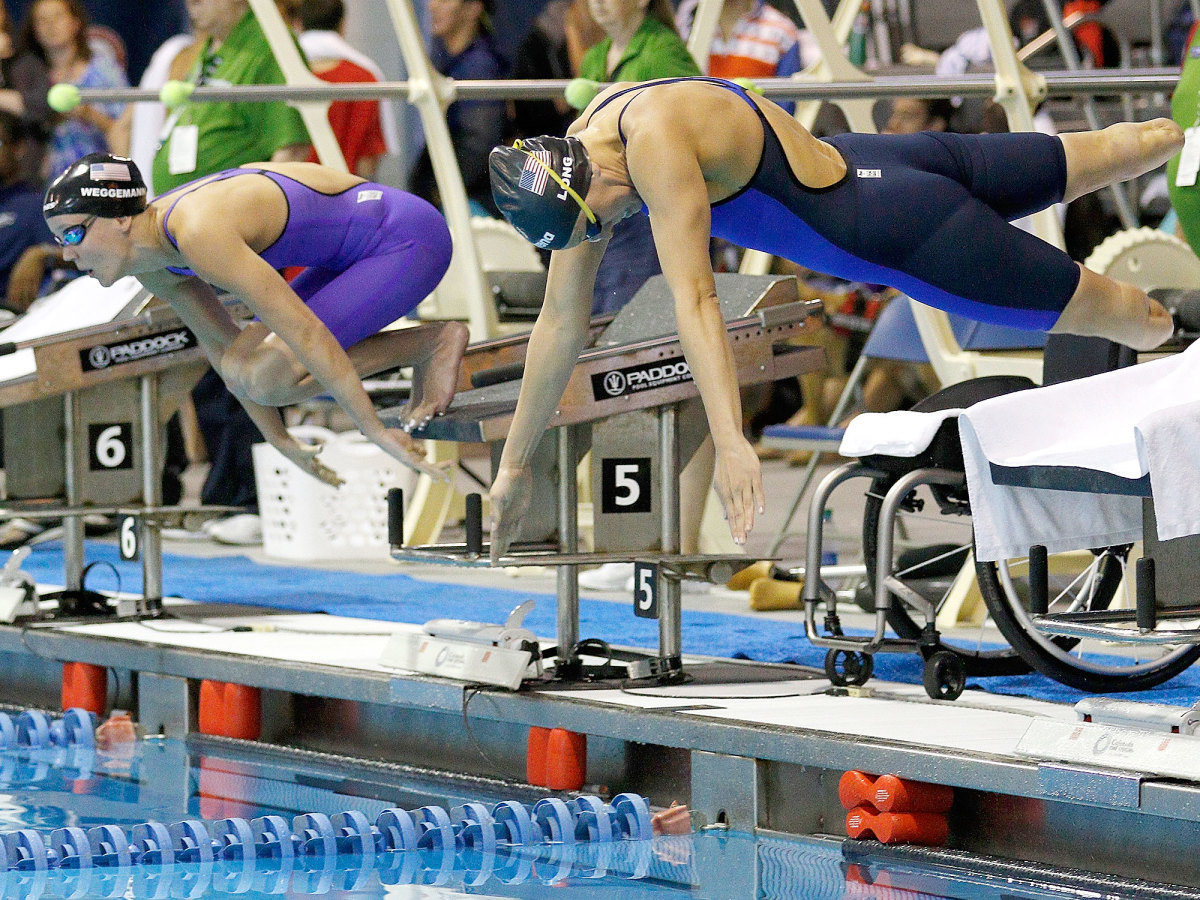

Almost none of her competitors in the S8 Paralympic classification are paralyzed below the waist like she is, and their left arms don’t spasm because of severe nerve damage. She simply removes her headphones, hoists herself out of her chair and onto the starting blocks and awaits the beep to start another race.

Weggemann’s paralysis at 18 years old thrust the Minnesota native into the challenging and confusing world of a life without functional legs. Like the millions worldwide confined to wheelchairs, Weggemann was now one subjected to entrances without proper handicapped access, narrow staircases that require somebody to carry her and the physical and mental overhaul required to live fulfilled in an able-bodied world. The paradox of water being a home for somebody unable to walk or kick isn’t lost on her. Yet salvation was the goal after her paralysis, and the water became her sanctuary. Maybe it always was.

• Meet Team USA: Brad Snyder, Jessica Long, other Paralympians

As Weggemann prepares to swim the 200m individual medley on Saturday, her biggest race of the 2016 Paralympics after not qualifying for finals in the 50m freestyle, it’ll be another mark in her transformation from paralyzed to Paralympic star and disability advocate.

“There is, at least here in the U.S., still is a stigma that goes with disability,” Weggemann says. “But I have confidence that I didn’t have eight years ago. What is so neat about Paralympic sports is that sports have the ability to transcend our physical ailments. The Paralympics use sports as a catalyst to change the perceptions of what it means to have a disability in our society. Not everybody uses that as their platform and driving force, but for me it is motivating.”

Like her two sisters, Weggemann was a high school swimmer growing up in the Minneapolis suburb of Eagan. Successful, but with no intentions of making it a career, Weggemann was set to attend Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, N.C. Having battled a nasty case of shingles that year, Weggemann was scheduled to receive three epidural injections to alleviate pain from the rash. It was after the third injection where she felt an unusual numbness and “heard the sound of my legs dropping very lifelessly and hitting the procedure table.”

“I remember Mallory looking at me like this was different,” her father, Chris, says. The numbness never cleared, and Weggemann, not long after posing at her high school graduation with a gleaming smile and leg kick, was left unable to walk. The Weggemanns are still loath to speak on the record why they didn’t pursue a malpractice suit against the doctor—they cite the power of the medical industry in Minnesota and legal advice that a lawsuit would be an enormous financial risk—but the family declined after two years of researching their options and chances at winning what promised to be a protracted legal battle.

Brad Snyder wants to be remembered more for his message than Paralympics medals

Shortly after her paralysis, Mallory was pointed to an article in the Minneapolis Star-Tribune about the 2008 Paralympic swimming trials taking place at the University of Minnesota. The water wasn’t a place she wanted to return after a series of torturous rehabilitation sessions in a hospital whirlpool, but she capitulated after some goading from her sister, Kristen. The evening was spent reminiscing about their swimming days and noticing a host of athletes—all of whom had either physical or cognitive disabilities—competing for an opportunity to represent the United States. After meeting a club coach from the University of Minnesota who offered to train her, Weggemann considered returning despite the seemingly insurmountable challenge of swimming without the use of her legs—her kick was her most powerful asset after all.

“When I got back into the pool, I started by racing nine-year-olds who were beating me,” Weggemann says. “But I knew I was back to racing, with each passing practice, I got faster and each was a new step forward. Swimming signified fighting back. I used to be comfortable anywhere, now I was now somebody with disability and I felt uncomfortable in my own skin. If one day I could break an American and the world record and become the fastest out there, that’s fighting back of the term and stigma of disability.”

The goal became the 2012 London Olympics. World records would be broken, sponsorships would arrive and an unlikely celebrity was borne in those four years. What she couldn’t predict were the politics that embroil the Paralympics and an improperly constructed shower bench.

Weggemann’s rise as a S7 Paralympic swimmer was swift, perhaps too swift in the eyes of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC). Paralympic classification is a complex and often controversial topic that confuses even the competing athletes. Because of the varying degrees of human physical and cognitive disabilities, the International Paralympic Committee has each competitor undergo a battery of physical examinations to determine which classification the athlete will compete under. Physical classifications range from S1 (most severe) to S10 (least severe); different classifications are awarded to the blind, deaf and cognitively impaired. Weggemann has a spinal cord injury, but raced against athletes with a wide range of disabilities (dwarfism, cerebral palsy).

Weggemann was originally classified S7, and she dominated the competition in freestyle and individual medley. Of the mindset that she would be competing against fellow S7 athletes at the London games, Weggemann was surprised to receive a note that she had been reclassified to S8 three days before she left for London. She refuses to speculate why this happened; some point to a video she did with Apolo Ohno where she appears to kick off of the wall despite her paralysis.

With no ability to appeal the decision, Weggemann’s dreams of nine gold medals at the 2012 games were erased. Instead, she focused on winning the 50 free and hoped to get any medal swimming against a new group of athletes. The race, even the athlete entrances, offer some insight into the cryptic world of classification and the skepticism that surrounds it. Weggemann is only one of two competitors who approach the starting blocks in a wheelchair, and the other (Great Britain’s Heather Frederiksen) walks from her chair into her starting place. During this year’s trials in Charlotte, Weggemann was usually the only S8 competitor using a wheelchair. It’s not an outright sign of corruption or malpractice, but it’s a confusing sight that somebody without the use of their lower body is competing against other competitors who have at least some.

Her ferocious late charge to win the 50-meter race in London offered relief from what she and her team perceived as an ambush from the IPC. She would add a bronze in the 4x100 relay. Her status as a competitive S8 swimmer was cemented despite the controversy.

Paralympics a source of inspiration, advanced technology and (yes) doping

“You can only control your reaction, and I could have shut down after the reclassification,” Weggemann says. “Or I could go fight for that ultimate dream for the Paralympic gold. It took support from coaches, teammates and supporters in that 50 free. Things around you can go wrong, but athletes are the ones who can control the final situation and outcome.”

But that wasn’t the end of her injury troubles or her reclassification issues with the IPC. While in New York City for a Today show appearance in 2014, Weggemann was showering in her hotel room when the bench—one supposedly approved by the American Disabilities Act—collapsed. Without the use of her legs to break the fall, her left arm smashed onto the shower surface, damaging the nerves from her elbow down. The injury kept her out of the pool for six months and immediately jeopardized her training for London. With several nerve endings wrecked, her arm periodically and violently spasms. Thus, her arm slapping against the water during a freestyle or butterfly triggers a nasty shooting sensation from her fingertips up and causes the arm to vibrate as if it’s been hit a heavy object. Some doctors recommended retirement. Memories of the trauma that stemmed from her initial paralysis crept back. After six years of tireless training to devote her life as a Paralympic swimmer, her future in the sport appeared to be waning.

“From 2009 to ’12 I was winning gold medals,” Weggemann says. “And all of a sudden I was at the bottom of the barrel again.”

With the help of a brace and hours of training with a heel strap to do pulling motions, Weggemann could at least mitigate—but not eliminate—the pain from the nerve damage. It still randomly pops up during standard daily activities and is exacerbated when she’s swimming. Despite the use of her left arm being restricted, the IPC ruled that Weggemann would remain at S8.

A win at the whistle: Against all odds, Rio de Janeiro pulls off the Olympic Games

“In terms of understanding [why I stayed in the S8 classification], I can’t tell you that I do,” Weggemann says. “Learning to adapt to the arm injury is different, one of the unfortunate components is that I have very severe tremors from fingertip into the neck and they are pretty much uncontrollable. I can’t control function when it’s happening. We’re learning to mentally handle how to do this, if this happens during a race then I just have to remain mentally tough. The water hurts. Getting touched, even lightly, hurts.”

“It’s been exhausting,” says Weggemann’s mother, Ann. “I don’t understand these rulings especially with an injury that severe."

Only 27 years old, the goal is to compete in 2020 at Tokyo. In the interim, she is intent on remaining a visible disability advocate. She caught the eye of Rep. Debbie Wasserman-Schultz (Fla.) during an assembly at a Hollywood, Fla. middle school, and has since become more involved with disability rights at a political level. Weggemann led the Pledge of Allegiance at the 2016 Democratic National Convention and often goes on press junkets for motivational speaking tours. Perhaps all of this would have never happened without her paralysis, but her fight back from the debilitating injury is why organizations routinely invite her as a speaker.

“Something horrible happened, but Mallory is the one to overcome it,” Chris says. “She lost the use of her legs and turned it into being one of the most visible disability rights advocates. She really does amaze me.”

The path to the 2016 Rio Paralympics became more challenging, but Weggemann qualified for the finals of the 200m IM. After failing to qualify for the 50m finals on Friday, Weggemann posted a heartfelt message on her Instagram lamenting the arm injury and the toll it has taken.

Saturday marks one more opportunity to again prove that she can overcome a life-altering injury and turn it into a gold medal. Whether her arm allows for that to happen remains to be seen.

The competitor in her is focused for Saturday. The advocate in her will push for the rights of those like her well into the future. But on Saturday? The focus is set.

“There was a time not too long ago when I was afraid I wouldn’t make the team,” Weggemann says. “Others didn’t think we’d be able to get back into the sport or compete. Many still doubt if I’ll be the athlete I once was. That lights a fire when you’re as competitive as I am.”