'Colorado Would Be Laughing Stock of the World': Remembering Denver's Disastrous 1976 Olympic Bid

The planning and execution of an Olympics is always a massive undertaking. It has been no different in South Korea this year, as the 2018 Winter Games kick off on Friday night. The Games are expected to cost $12.9 billion, almost double the projected cost. Venues will have little-to-no use afterwards. Olympic Stadium in PyeongChang—cost of construction: $109 million—will be used four times, in total (for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies of the Olympic and Paralympic Games). For a time, Gangneung Ice Arena was going to be used as a seafood freezer post-Games, but that idea has since been nixed.

Across the globe, there’s been an increased outcry against these expenditures. Boston’s bid for the 2024 Olympics was nixed as citizens began to loudly express their displeasure. Budapest withdrew its bid for the 2024 Games after residents collected enough signatures to force a referendum. Krakow’s bid for the 2022 Games failed after 70% of the residents who voted on the referendum chose no.

These acts of citizen opposition are becoming more common, but they are certainly not new. In 1970, Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics, meant as a celebration of the U.S. bicentennial. Just two years later, due to a combination of public pressure and organizational ineptitude, the Games were handed back to the IOC, away from Denver, and into the hands of Innsbruck, Austria.

The story of the failed Denver Games is one of crass opportunism. It’s one of a savvy opposition group. It’s also a roadmap for cities across the world that, in the words of the Colorado city, don’t want to “Olympicate.”

It was supposed to be the “Economical Games.” The 1972 Winter Games in Sapporo had cost $1.3 billion. Grenoble in 1968 had cost $250 million. Denver promised to host the the Games on the cheap. Organizers said it would only cost $14 million—and Governor John Love said only $5 million of that would come from state taxpayers.

“Is $5 million, one quarter of one percent [of government services] too much to spend for the excellence and pride and an international celebration in the 100th year of Colorado’s statehood and the 200th year of our nation?” Love said in a speech to a joint session of the state legislature.

But Coloradans would never spend $5 million. Increasingly, shoddy planning meant that costs kept skyrocketing. There was a chasm between the proposed plans and the on-the-ground realities. Consider how it played out:

- The Olympic Village was supposed to be at the University of Denver—during the school year!—but no discussions with the university had commenced.

- The Denver Olympic Organizing Committee (DOOC) said there were hotels for 100,000 visitors, but there was only room for 35,000.

- Events were supposed to be within a 45-minute drive from the University. But, to take one example, Mt. Sniktau, the home of downhill skiing, was 50 miles away. And, oh by the way, it didn’t get much snow. Home mainly to climbers, the mountain wasn’t ideal ski terrain because it fell on the east side of the Continental Divide, on the opposite side of the typical ski resorts in Colorado. Said Pete Wingle, a U.S. Forest Service Officer: “If you and I were going to build ourselves a ski area, we wouldn’t put it at Sniktau.” When the organizers proposed the site, they had an artist airbrush snow onto the mountain.

- Time to scratch the 45 minutes from the University idea, because quickly, events were going to have to be held in Vail and Steamboat Springs. Steamboat Springs is 160 miles away from downtown Denver. The new idea? Let’s build an airborne taxi service! It would work like this: Walter Schirra, one of the original Project Mercury astronauts, and the ninth person in space, served on the organizing committee and proposed using DHC-6 Otters to ferry people between the cities. Otters can hold up to 20 people.

- In Evergreen, a tiny Denver suburb, the chances of snow in February are around 1 in 25. So, naturally, it would be the perfect spot for biathlon. Some of the routes, it appeared, would go through homes and schools. That wasn’t quite true, said Norman Brown, the DOOC vice president: “Actually, the trails are only eight feet wide and don’t go through any buildings—just backyards and the WIlmot schoolyard. Some people would have to let us put gaps in their fences.”

- The ski jump, also in Evergreen, posed problems. Organizers would have to bulldoze a hill, reroute a residential road, and put concrete over Bear Creek. This, Brown admitted, wasn’t the smartest idea: “This plan was drawn by an architect from Chicago. I’m not sure he knew what he was doing.”

- And then there was bobsled. As costs piled up, building a bobsled track started to look untenable. But to eliminate bobsled would be, as Amilcare Rotta, president of the International Bobsled Federation, said, “unthinkable.” The next best plan? Hold bobsled in Lake Placid. That’s right. While the entirety of the 1976 Games would happen in Colorado, bobsled would be isolated in New York’s Adirondack Mountains, 1,875 miles away. Besides being impractical, it was foolish. (To be fair, in Rio in 2016, the distance between the Amazonian Arena for soccer and the Olympic BMX Center was 2,663 miles.) While building a bobsled track would be expensive, they were going to fund a luge track for $3 million. A bobsled track, one would think, could be fashioned somehow.

This litany of issues made it clear that the DOOC had oversold their position. They had two core problems, each elucidated in rare moments of candor by politicians. Said state senator Joe Shoemaker: “One of your problems, as far as I’m concerned, is that you don’t have a plan.”

And as acting governor John Vanderhoof put it: “[The DOOC] were pressed for time, so they lied a bit.”

Dick Lamm always had a bit of firebrand to him, and he still does today. The former Colorado governor now serves, at age 82, as the co-director of the Institute for Public Policy Studies at the University of Denver. A former presidential candidate on the reform party ticket, Lamm’s political career took off because of the Olympics, and is still warning about its excesses

“The Olympics,” he told SI recently, “did not seem to offer much about the quality of life.”

As a state legislator in the late ‘60s, Lamm voted for the Olympics to come to Denver. As the costs kept rising, he quickly began to publicly disavow it and campaign against it.

He was joined by fellow state representative Bob Jackson. Jackson said the the DOOC was guilty of “tragically inept planning.” And, despite Lamm’s assertion that the DOOC consisted of “good people,” Jackson was right. The DOOC apparently didn’t realize they would need to contribute to NBC’s costs for coverage. Said NBC executive Carl Lindemann Jr.: “What it really comes down to is that they are just so wrong. They think television is going to make it all an expected profit of $9 million for them, when really they are going to have to put up money to even make the broadcasting thing happen at all.”

This led to the joint budget committee of the legislature cutting the DOOC’s appropriation request by more than a third. Employees were cut from 21 to 10, and money for promotional trips and ticket sales was slashed.

Despite that crippling blow, William Nelson, a spokesman, told a group of Kiwanis members in Fort Collins that the Games, “are set.” He said it would amount to $17.5 million.

But that number was flat-out wrong. A state legislator said a month earlier that the Games would cost $63.3 million, much more than an earlier $35 million estimate. It broke down as follows:

- $19 million for construction

- $15 million to stage the Games

- $26 million for press housing

- $2.2 million for athlete housing in Steamboat Springs (now one of three Olympic villages)

- $3.1 for remodeling work

And that didn’t include a study by an architectural firm that was at odds with the city’s estimates. The cost to purchase 58.85 acres of land for a new stadium, according to the study, would be more than $1 million higher than what the city sought. In all, the arena would cost almost $4 million more.

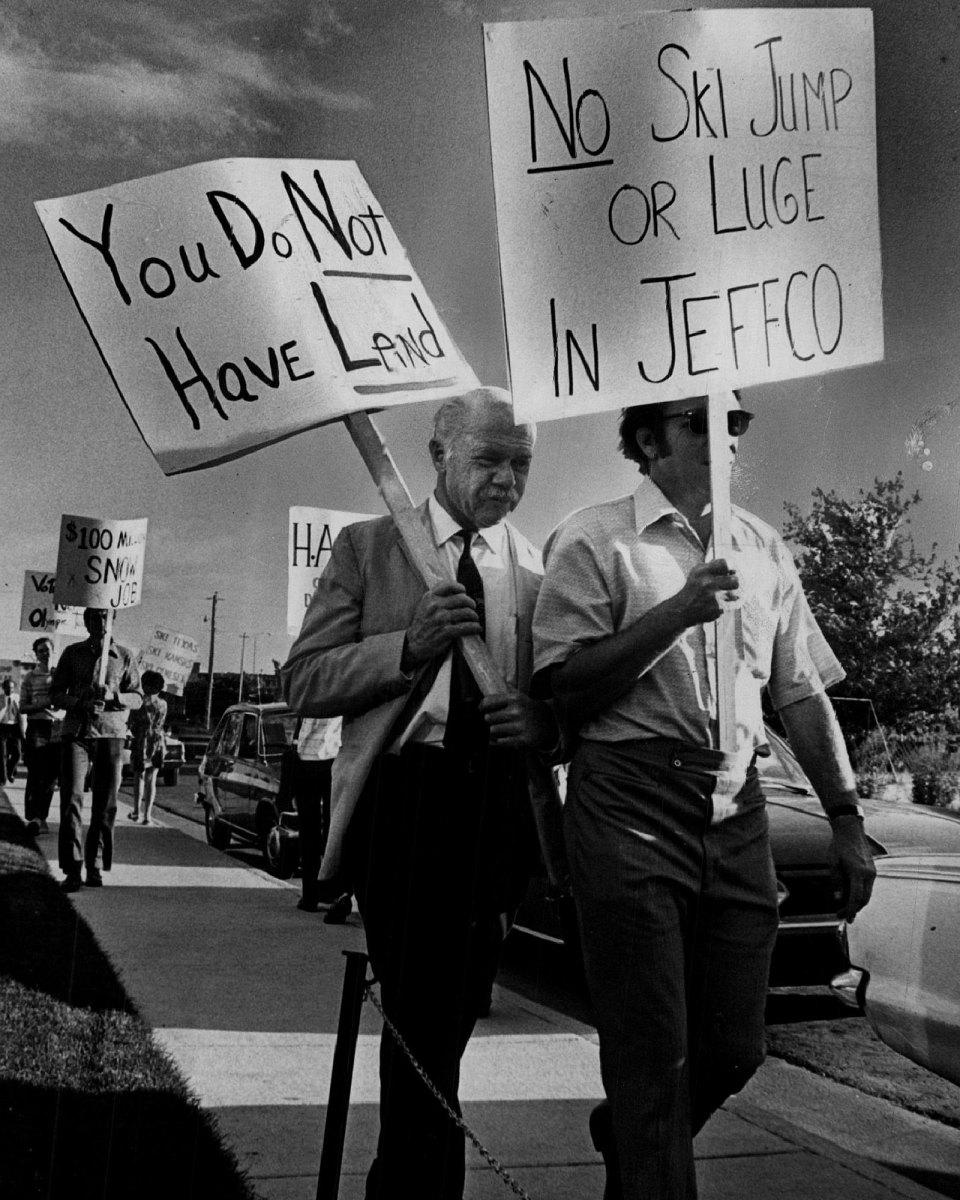

The trickling out of these numbers started to ignite the opposition. John Parr, coordinator for Citizens for Colorado’s Future, led a staff of four to get 77,392 signatures in a month. “We’ve developed the type of grassroots movement politicians dream of,” he said. That forced a ballot initiative about further funding the Games. They were one of a few groups, combining environmental and economic concerns. The Protect Our Mountain Environment was particularly involved in Evergreen. “It’s not just that we want to protect the local environment from the bulldozers and parking lots,” Vance Dittman, the chairman of POME, said. “We’re simply convinced Colorado would be the laughing stock of the world if it tried to stage the Olympic events here in February.”

The grassroots effort was split evenly between the two concerns, according to Lamm. More than anything, it was about responsible growth. “The growth issue has always been big here in Colorado,” he says. “More and more people were asking, why spend all this?” (Lamm said pretty much the same thing to SI in 1972: “We’re starting to realize that growth isn’t necessarily good.”)

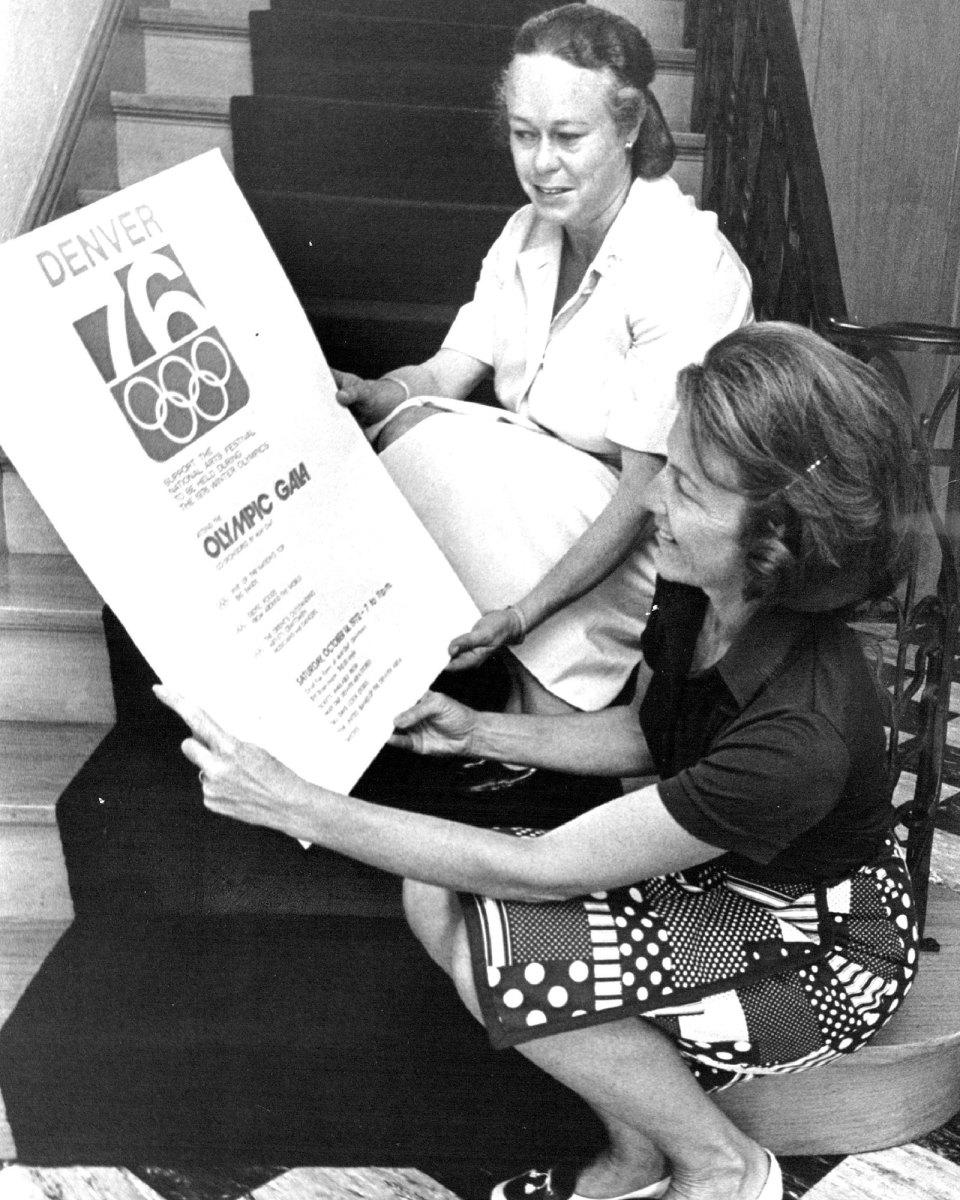

The DOOC began to organize a counter-campaign, funded at $150,000. Luminaries like Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Milton S. Eisenhower were brought to rally support. Jesse Owens glad-handed.

The DOOC tried to portray the image that the protesters were in the minority. Carl DeTemple, the president, wrote in a progress report: “We do recognize that members of the International Olympic Committee have received written objections to the staging of the 1976 Games by Denver. We hope that you do not accept these expressions as representative of the convictions of the more than 2.5 million residents of Denver and Colorado.”

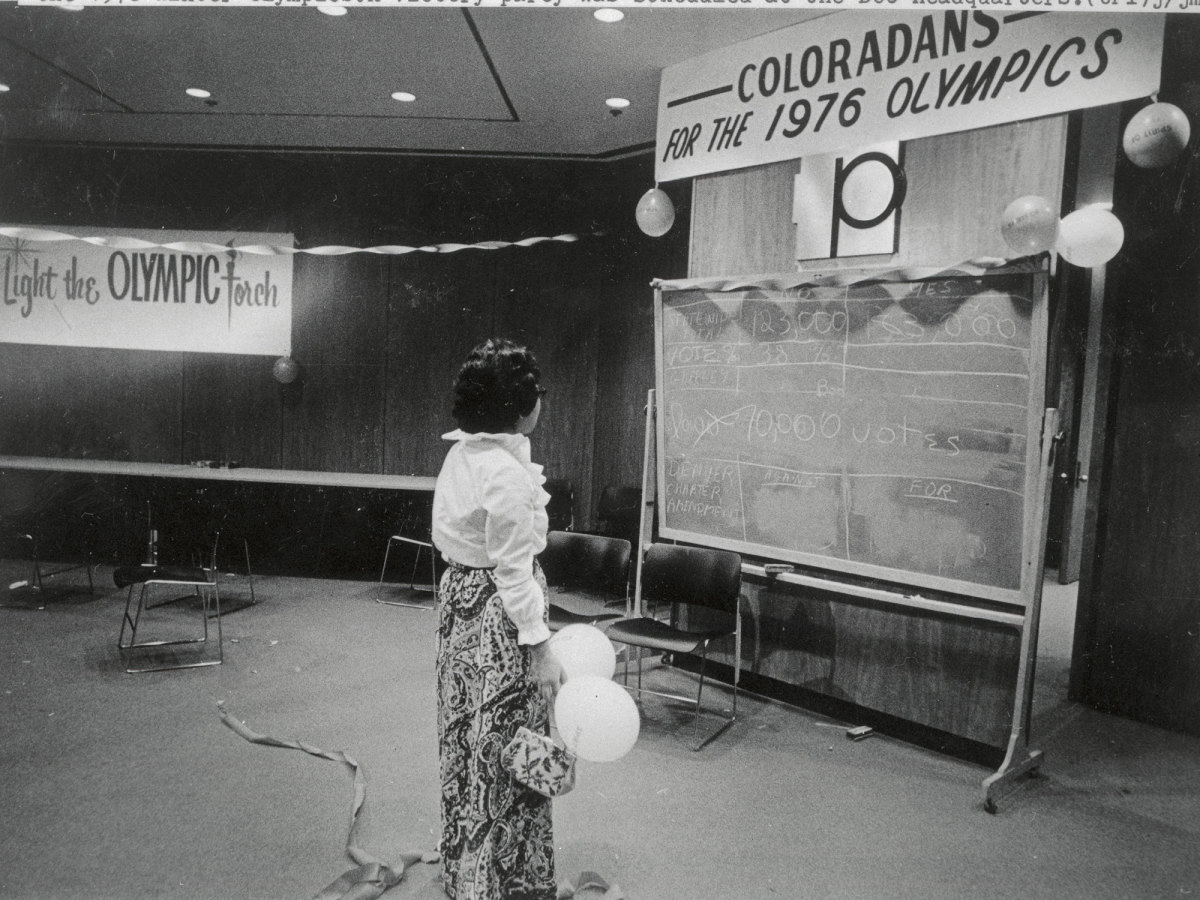

But that was a facade. Polling found that voters, by a 3-1 margin, did not think that the DOOC had been candid about costs. Momentum had shifted. A vote against the Olympics would be, according to Don Magarrel, who made the initial Olympic presentation to the IOC, “the worst international disgrace in American history.”

The vote went as planned. Voters approved the constitutional amendment prohibiting further state funds for the Games by a margin of 537,440 to 358,906.

The grassroots campaign was a resounding success, and the biggest beneficiary was Lamm. “The night of the Olympic vote, one of our organizers held me up to the ceiling and said, Ladies and Gentlemen, the next Governor of Colorado!” Lamm recalled. (Lamm was elected in 1975, and served three terms. He ran for Senate in 1992, but lost, before running for the Reform Party nomination in 1996, where he lost to Ross Perot in the primary.)

While there was some backlash to the vote—there was a quick effort from the Colorado Committee to Save the Winter Games to get an injunction, but it went nowhere—the Games quickly disappeared from Denver. Three months later, the IOC gave the Games to Innsbruck, who had previously hosted it in 1964.

The Denver experience most likely taught the IOC to vet host cities better—it would be unlikely to see a city give back the Games nowadays. Years of planning go into bids to make sure they are viable. One of those efforts is going on right now in Denver.

The USOC has said that Denver, along with Salt Lake City and Reno, are in the running for a bid in either 2026 or 2030. In December, mayor Michael Hancock formed the Denver Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games Exploratory Committee, with members such as Governor John Hickenlooper, Peyton Manning and Chauncey Billups, among others.

Denver would certainly learn from its failures in 1972, and, perhaps, not worry about hosting an “Economical Games.”

But to Lamm, there’s a bigger question.

“I expect that Colorado, under the right circumstances, could host an Olympics. I just don’t know why we would want to.”