The Fall ... And The Photo ... Of A Lifetime: Revisiting Hermann Maier's Olympic Crash, 20 Years Later

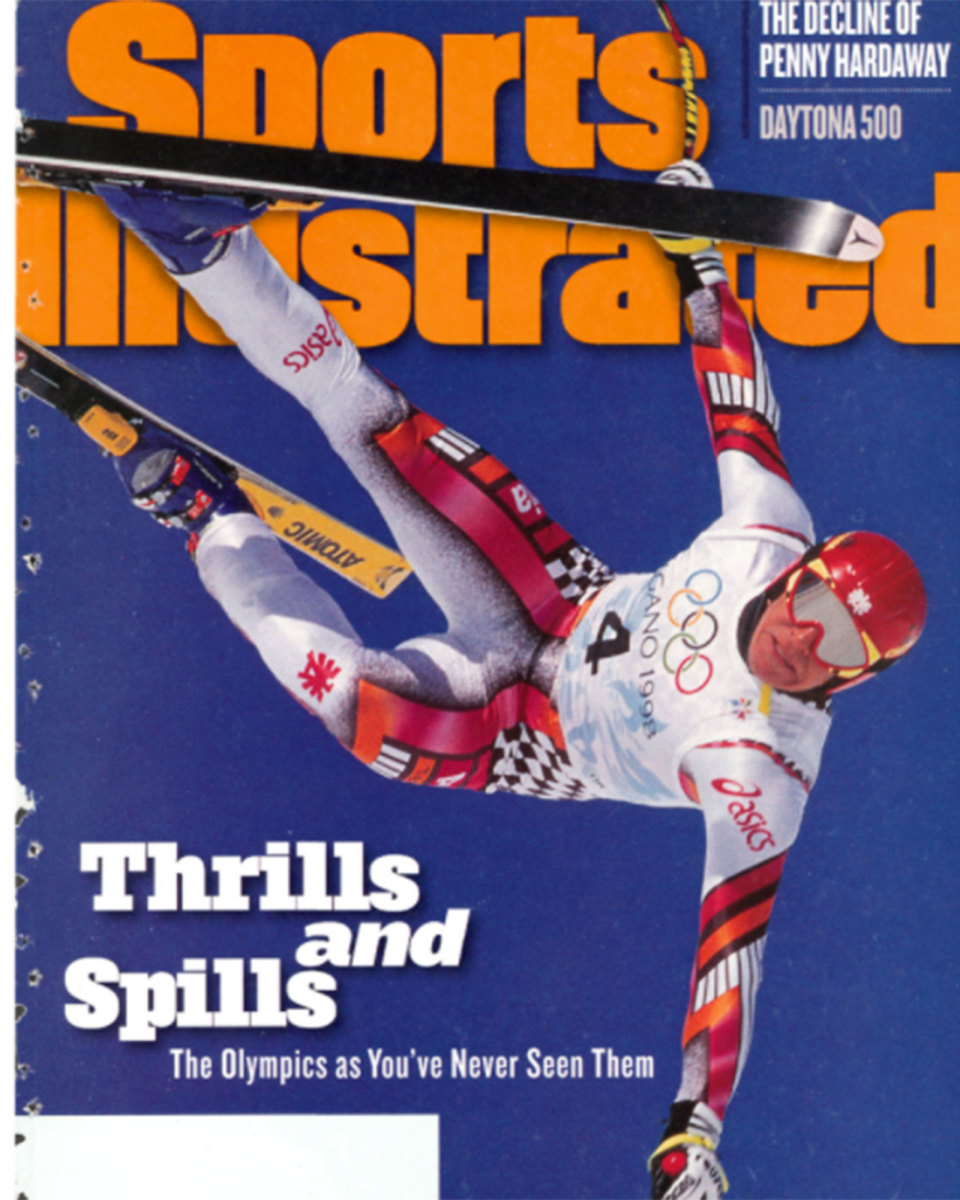

It’s best to start with the photograph, published on the cover of the Feb. 23, 1998 issue of Sports Illustrated. It is by definition action sports photography, but that does not do justice to the picture, or the moment. A ski racer is frozen against a blue sky, aligned as if heaved into the air from the side of a swimming pool. His gloved hands are pointed at twelve and six on the face of a clock, clutching poles that were vital to his task only seconds earlier but which are now useless. His skis are above his head, also not only useless, but dangerous. He is wearing a speed suit in the red, white and black colors of Austria, his powerful thighs stretching the fabric. Again, useless. A helmet covers his head. Not useless.

He is grimacing, stretching his lips wide and baring his upper teeth, as if processing his predicament in real time, and bracing for impact. “That shows how much time I was in the air," he says, years later. Less than two seconds, in truth. But also an eternity. It is not just a photograph, it is The Scream.

The man in the picture is Hermann Maier, one of the best ski racers in the sport’s history. Twenty years ago, as the overwhelming favorite in the Olympic downhill, a 25-year-old former bricklayer who had seized the sport and shoved it forward on the evolutionary timeline with his strength, intensity and go-for-broke, borderline reckless tactics, Maier flew off a mountainside overlooking the Japanese alpine village of Hakuba, 30 miles from the Olympic city of Nagano. There have been many worse crashes in the long and harrowing history of downhill racing; men and women have been killed. But there has never been a more memorable wipeout on a bigger stage by a better racer, an operatic flight across a crystalline sky that ended only after a hard landing and then a tumble through three primitive and ineffective safety nets.

And only when a man who was—and still is—called the Herminator improbably rose and wagged his right index finger. And then went on to win two gold medals with a body that should have been broken into small pieces by his fall.

The story of the crash begins with the unlikely story of Maier himself. He arrived in Nagano having won 12 World Cup races in a year, including a mind-boggling five-race winning streak in January preceding the Olympics. He had won races in four of the five alpine disciplines. On the surface, it is not unusual that an Austrian man would emerge as his sport’s newest and biggest star. The Austrians were, and are, to skiing what Jamaicans are to sprinting. But Hermann Maier was a decidedly unlikely Usain Bolt. In the midst of his winning streak, Sports Illustrated sent me to Austria (with the great multilingual reporter, Anita Verschoth) to profile Maier. Together, we went to Maier’s hometown of Flauchau and eventually to the ski mecca of Kitzbuhel, where, on the snowy afternoon several days before the Hahnenkamm Downhill, we sat in a hotel restaurant and interviewed Maier. We eventually produced this story.

The key section is here:

Maier's father, also named Hermann, is the owner of a ski school who put the older of his two children on skis at age three. "Two days later he was off riding the lift by himself," says the father. From the beginning, young Hermann was possessed of a brilliant touch on the snow and perfect posture on his skis. But he was also tiny, with skinny, perpetually sore knees. In the fall of 1988, when he was 15, he was accepted into the national ski academy at Schladming, but he weighed just 110 pounds. After one year he was gone. "They said I wasn't fit to ski in their school," says Maier.

He went home to Flachau and at 16 became a bricklayer's apprentice, beginning work in a trade that he would practice for the next seven years. (He's now a journeyman.) His classmates at Schladming continued training and competing. In the voracious Austrian system, Maier was dead and forgotten. Yet his ambition thrived. "I trained every day for my comeback," he says. In the spring, summer and fall of each year he worked as a bricklayer and stonemason, hauling 110-pound bags of cement and pushing wheelbarrows full of brick and stone. His body quickly grew tall and wide; at 17 he was 5'11" and nearly 200 solid pounds. In the winter he taught at his family's school, Schischule Maier, one of five—no lie—ski schools in the hamlet of Flachau (pop. 2,500). "He was giving lessons five hours a day and skiing on his own the rest of the time," says the older Hermann. "I think all that practice is why he's such a good, instinctive skier."

It was a remarkable tale, like Kurt Warner plucked from a grocery story in Iowa. But Maier did not just win races, he changed the sport of alpine ski racing. His intensity before races, in the seconds before pushing from the start house and down the perilous slopes of the World Cup, was unlike his opponents had ever seen.

“He was like a rabid dog in the start house,’’ says A.J. Kitt, who was a downhiller for the U.S. team, nearing the end of his career when Maier arrived.

“Hermann Maier came onto the scene, and he was just a little more intense than anyone else,’’ says Tommy Moe, who won the gold medal for the U.S. in the 1994 Olympic downhill.

“I remember he would inspect the course, and he would spend every last minute, just totally studying, memorizing. And then in the starting gate, his eyes were just so intense. He looked like he was ready to kill somebody.’’

But it was not just intensity with Maier. He transformed the tactics of elite ski racing, taking strategic lines that were more direct—and more risky—than anyone before him, while taking advantage of, and accelerating changes in the technology of the sport. “His approach, his athleticism, his technical ability, all of those things,’’ says Kitt. “The sport was changing on its own, with shaped skis and turnier downhill course. And Maier took advantage of those things.’’

Kyle Rasmussen, who also raced for the U.S. against Maier, says, “He evolved the sport. And he took it to a whole different level. At the time, you would watch him race, and think, man, I don’t think I can do that.’’

He came to Nagano as a rock star, the best racer on the best team, a force of nature. He had been nicknamed ``The Herminator,’’ in homage, of course, to his countryman, Arnold Schwarzenegger. He was favored to win three events at the Olympics. “It was my first proper season,’’ wrote Maier in an email to SI. “I won every Super-G, came to Nagano as the overall World Cup leader. Even though it was my first Games, it’s clear that you go all the way to make your childhood dreams come true. Obviously, I was too confident.’’

Well, that, and the Olympics went briefly off the rails.

"It was a combination of little downhill experience, ferocious determination and youthful recklessness.’’

It was long known coming into the Games of ’98 that weather could be a problem. The alpine speed site in Hakuba was known for severe extremes: Wind, rain and blizzards that accumulate snow in feet, not inches. The downhill was scheduled for Sunday, Feb. 8. Before it would actually take place, all three extremes would pound the mountain. The race was postponed three times over five days. Finally on a clear, cold Friday morning, a full week after the opening ceremony, the race was a go. Fittingly, it was Friday the 13th.

And even on this day, there was a delay. Wind blew from the top of the barren mountain, creating a tailwind that would complicate racing strategy. Additionally, the seventh gate on the course, at the bottom of the initial drop and just before a left turn, was moved to the right and created a sharp and difficult transition to the next drop. Racers would have to ski very cautiously to make the turn or risk losing control and missing the next gate… or worse. But there is also some question as to how many racers knew about the movement of the gate. “We didn’t know,’’ says Kitt. “I think the only teams that knew were the Austrians and the French.’’

Maier says, “It seemed that a few gates had been moved, especially the seventh gate, which became my fate.’’

The third skier down the hill was Jean-Luc Cretier of France, who had never won a World Cup race. Cretier tucked down the initial drop and then, literally, stood up on his skis approaching the seventh gate, cleared it easily and navigated the rest of the course. Waiting to ride the chairlift to the top, Rasmussen saw Cretier’s tactic and thought: That makes a lot of sense. I’m going to do that, too.

Moe remembers: “The way they changed it, it became an unnatural turn. You had to dump some speed or you weren’t going to make it."

Maier was next after Cretier. He did not dump any speed. Where Cretier stood up to slow down, Maier carved hard across the hillside, maintaining his speed. “I’m still convinced it was the fastest line,’’ Maier wrote to SI. ``But unfortunately it turned out to be not feasible. At least not with the strong backwind, which I completely ignored because of motivation. It was a combination of little downhill experience, ferocious determination and youthful recklessness."

Rasmussen was watching from the chair lift. “I thought, oh my god, he’s dead.’’

Maier dove into the turn hopelessly fast, riding his right ski hard. As he tried to complete the turn and transition to his left ski to make the next gate, his right ski released and threw Maier into the air, as if bounced from a trampoline. At the bottom of the hill, where the race was projected on a video screen, there was a collective gasp. He sailed off the course and landed hard on his left shoulder and then bounced through three orange fence-nets before coming to a stop on his stomach. Rasmussen was watching from the chair lift. “I thought, oh my god, he’s dead."

“My mouth was full of snow, that I had to spit out first,’’ says Maier. “After I got my breath back, I thought, get up quickly to calm my family back in Flachau that watched the race on TV. Otherwise I would have laid down a bit longer."

There were skiers that day who saw Maier’s epic crash as comeuppance for his season-long daredevil lines. At the time, Rasmussen said, “It was a matter of time until this happened.’’ Cretier, who won the race (and never won again afterward), said, “Today you had to ski with your head, and not your legs."

In the video of the crash, as Maier struggles to his feet, you can barely see the legs of a man moving quickly in the snow, perhaps 20 feet up the mountainside from Maier. That man is Carl Yarbrough, then 41, a freelance photographer shooting his sixth Olympic Games, this one for Sports Illustrated. It was Yarbrough—and Yarbrough alone—who captured Maier’s fall…or flight?...on film. “My moment in the sun," he calls it.

Yarbrough was a successful and well-compensated commercial photographer, specializing in outdoor winter shoots where he could utilize his advanced skiing ability. He also had shot every Olympics since 1980 in Lake Placid. However, his presence in Nagano was serendipitous. Yarbrough had gone to Lillehammer for SI in 1994, and had one of the worst experiences of his career. “The temperature never got above zero, I had dysentery and I didn’t get a single picture published.’’

Because of his skill on skis, Yarbrough was often able to reach places on the mountain that were inaccessible to photographers who did not ski as well as he did, or did not ski at all. But that can entail setting up in areas that are not, strictly, legal. On the day of Moe’s downhill win in Lillehammer, Yarbrough was tossed from his location by an official and forced to shoot with others lower on the hill. And then he missed Moe when a Norwegian official excited over Kjetil-Andre Aamodt’s leading run failed to alert Yarbrough to Moe’s approach.

“It was a terrible shoot,’’ says Yarbrough. “I just thought after that, you know what, I’ve had a good career. I’m done with ski racing.’’ Four years later, then-SI director of photography Steve Fine convinced Yarbrough to give it another shot.

Over several days of training runs, Yarbrough tested locations high on the mountain. While many photographers like to pick a spot where a skier will catch air, Yarbrough liked sharp turns, where a skier angulates his (or her) body and carves. He immediately liked the spot where Maier would eventually fly. To enchance his spot, Yarbrough McGyvered a platform with a slab of plywood from a construction site and a ladder he bought at a hardware store. Five days of delays buried his equipment under two feet of snow, and on the day of the downhill race, Yarbrough spent two hours digging out his equipment and setting up his platform. Soaked in sweat, he shot the race in a t-shirt.

“I figure if I missed it, I’m gonna want to drink,’’ says Yarbrough. “If I got it, I’m gonna drink.’’

There was one problem: Yarbrough was shooting blind. He couldn’t see the racers until they were in his frame. “So I would listen for the sound of skis,’’ Yarbrough recalls. “And then as soon as I saw a flash of any color, I would just lay on the motor drive and just hope I had something.’’ (It’s important even for non-photo nerds to understand that Yarbrough was shooting with film, before auto-focus. He had pre-selected an aiming point).

Just before Maier went out of the gate, Yarbrough hurriedly moved his platform and ladder 20 feet further up the hill to enhance his angle. He prepared and heard nothing, because where other skiers had been carving along the snow, into the turn, Maier was losing contact with the snow. “I had no audible cue,’’ says Yarbrough. “I saw a flash and fired off eight frames in about three-quarters of a second.’’ Yarbrough didn’t know if he had a great picture or nothing at all. He went to a bar with friends. “I figure if I missed it, I’m gonna want to drink,’’ says Yarbrough. “If I got it, I’m gonna drink.’’ Fine called him shouting into the phone. “I can’t believe you got this!’’ (I was with Yarbrough that night. Indeed, we drank. I still have the headache).

The photo was on the cover of the magazine, with Maier splayed horizontally. Maier has signed the image thousands of times. “I still don’t know how to turn it right.’’

The crash is the enduring memory of Maier’s Nagano Olympics, but there was more. The night of downhill, Maier visited with a small group of writers at a hotel in downtown Hakuba. He said with a growl that I will never forget, “Yah! My first big crash in downhill.’’ Asked about flying through the air, he said, "Not like Lufthansa.’’ His shoulder was sore, but the bigger problem was a badly bruised right knee.

The Super-G was scheduled for the next day, but again, postponed by heavy rain. And postponed again the next day. The delays allowed Maier to recover sufficiently to race his favorite event. How? “With cold pressure dressings and workouts on an ancient Japanese bicycle,’’ he says. “It helped of course that it was pouring and the Super-G could not take place the next two days. The first day I couldn’t even bend my knee.’’

On Feb. 16, Maier won the Super-G, his first Olympic gold medal. Three days after that, he won the giant slalom. Hence: One Olympics, two gold medals and one memorable flight.