One Year Out: What to Watch Ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

One year from now, the flame will be lit in Tokyo, the XXXII Olympic Summer Games will begin, and Americans will set aside their differences for at least 30 seconds before pushing each other into the fire. This is where we are, America. We have a year to decide if it’s where we want to be.

The Olympics, to some degree, are inherently political, and they occasionally become the backdrop for protest, such as Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s podium demonstration against racism in 1968. But nowadays nobody sticks to sports anymore, it seems, and so the event that used to (more or less) unite us faces an odd challenge. Will American athletes make it political? If they do, will you hold it against them? If they don’t, will you hold it against them?

The last Summer Olympics, in Rio in 2016, took place three months before the election of President Donald Trump. Partisan tensions have risen considerably since then, even in sports. The recent Women’s World Cup was a prime example: The triumphant Americans are surely more popular among liberals than conservatives. This is not the prism through which we viewed Michael Phelps or Jackie Joyner-Kersee.

The 2020 Olympics could be the ugliest American visit to Tokyo since former President George H.W. Bush vomited in the lap of Japanese prime minister Kiichi Miyazawa. Las Vegas sports books should set an over/under of how many American athletes the President will trash in the middle of the Olympics. After all, he frequently targets immigrants, and nearly 50 foreign-born Americans competed for Team USA in ’16.

How many athletes will use their visibility to criticize Trump? The U.S. men’s basketball coach, Gregg Popovich, has been one of his most vocal critics in sports. Still, athletes do not become the best in the world so they can tell people whether they plan to visit the White House. But that question is fair, and it’s coming. Let’s hope it doesn’t overwhelm the event.

The Games always deliver, despite myriad scandals. (Drugs and money are as much a part of the Olympics as the rings.) There will be unpredictable triumphs and heartwarming stories, brutal defeats and affirming acts of sportsmanship.

Simone Biles’s performance in 2016 was mesmerizing; what she does in ’20, after her courageous admission that she was sexually assaulted by Larry Nassar, will be inspiring, no matter where she finishes.

Katie Ledecky may win so easily that she’ll be able to read a book while the other swimmers finish. Noah Lyles will try to become the first American man since Carl Lewis to win the 100- and 200-meter sprints, but teammate Christian Coleman might get in his way, though hopefully not literally.

There will be quirky developments and seemingly random events. The IOC added three-on-three basketball; the favorites are the U.S. team of James Harden, his agent and his personal chef. For the first time, all six fencing team events are on the docket, a relief to all the men’s team-saber enthusiasts who were disconsolate watching the Rio Games. Skateboarding could become the summer version of slopestyle skiing—the wildly entertaining sport we didn’t know we needed.

Baseball will be back, and while America does not need more televised baseball games, Japanese fans will make the event a spectacle. The return of softball is more welcome. We are indifferent about the addition of karate but do not plan to say that to anybody who competes in karate.

Grammarians will applaud the lack of a hyphen in sport climbing; competitors will climb walls—not another sport. Sport climbing includes three disciplines (speed climbing, bouldering and lead climbing, but you knew that), and if it is a hit, the Tough Mudder lobby will be at IOC headquarters with a briefcase of cash.

One small prediction: The most popular new sport will be surfing. It will appeal to surfing experts, climate scientists, attractive-body enthusiasts and fans who pretend to understand the scoring system.

Mostly, though, there will be swimming, and there will be wrestling; there will be track, and there will be field; there will be records set, and there will be tears spilled. The Olympics move us because they are a break from the sports we hear about all year round. We will find out if these Olympics are a break from our divisive political discourse, too.

—Michael Rosenberg

Scroll down for detailed previews on Tokyo 2020's major sports, including storylines and athletes to watch, key dates and more.

TRACK AND FIELD

FAMILIAR NAMES LIKELY COMING BACK

• Justin Gatlin

• Mo Farah

• Emma Coburn

It’s often difficult to pick U.S. stars who will be at the next Summer Games because the U.S. Olympic Trials can often lead to upsets and wild finishes that leave some top athletes watching from home on their televisions. But for Olympics fans, these are three of the most recognizable names in track and field that we should see again in Tokyo.

Justin Gatlin has been around forever, winning the 100m dash all the way back in 2004 in Athens, and is also well-known for serving a four-year doping ban from 2006-2010. He finished second in the 100m to Usain Bolt in 2016, then beat Bolt at the 2017 world championships. He took 2018 to rest and despite being 37 years old, he's run a season's best of 9.87 in 2019. He could still contend for an individual 100m spot in Tokyo but will almost certainly be part of a relay.

Great Britain’s Mo Farah capped the “double double” in Rio and became the first runner to win the 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters at consecutive Olympics since Finland's Lasse Viren at the 1972 Munich and 1976 Montreal Olympics. He competed in both events at the 2017 world championship in front of a home crowd in London but had to settle for silver in the 5,000 meters. It snapped hopes of a third consecutive “double double” at worlds but shifted his focus to the roads and the marathon. He won the 2018 Chicago Marathon and has lowered his personal best to 2:05:39 as he looks to try to claim gold in the marathon in 2020.

Emma Coburn, the 2016 steeplechase bronze medalist, made history by becoming the first American woman to win world championship gold in the steeplechase. She's since become more of a household name, appearing in ESPN The Magazine's Body Issue, landing ninth on SI's Fittest 50 list for 2019 and serving as a vocal advocate for clean sport by calling out suspected drug cheats.

Plenty of other American medalists from Rio have great shots to return to the Olympics. Among them:

Ryan Crouser (2016 shot put gold medalist) is nearly a lock to compete in Rio barring any injury or unforeseen circumstances. Christian Taylor (2016 triple jump gold medalist) has won gold at the last two world championships. Evan Jager (2016 steeplechase silver medalist) remains the top U.S. steeplechaser and added a bronze medal at the 2017 world championships. Clayton Murphy (2016 800m bronze medalist) is just 24 years old and remains one of the best U.S. middle distance runners. Paul Chelimo (2016 5,000m silver medalist) has become the United States’ best 5,000 meter runner with a bronze medal at the 2017 world championships. Jenny Simpson (2016 1,500m bronze medalist) remains one of the two best 1,500 meter runners for the U.S. and will be going for her third Summer Games. Courtney Frerichs took silver to Emma Coburn in the steeplechase at the world championships, then later beat Coburns’s American record. Sandi Morris (2016 pole vault silver medalist) added a silver medal at the 2017 world championships. Michelle Carter (2016 shot put gold medalist) added a bronze medal at the 2017 world championships.

And two more international stars who wowed in the 2016 Olympics that may be back in 2020:

Wayde Van Niekerk provided one of the best moments on the track in Rio, breaking Michael Johnson’s 400-meter world record, which had stood since 1999.

And in the final athletics event contest at the Olympics, the men’s marathon, Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge will likely be vying to become the first man since 1976 to successfully defend his Olympic gold medal. Since his win in Rio, Kipchoge cemented his legacy as the greatest marathoner of all-time by attempting to break the two-hour barrier under optimized race conditions in an exhibition marathon put on by Nike in May 2017. He ended up covering the 26.2-mile distance in a remarkable 2 hours and 25 seconds but it did not count toward a world record due to Nike’s use of alternating pacers. However, he finally nabbed the world record in September 2018 with his 2:01:39 win at the Berlin Marathon—which took 78 seconds off the previous best. A loss in Tokyo would be a tremendous upset since Kipchoge has not lost a marathon since 2013.

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

• Usain Bolt

• Ashton Eaton

• David Rudisha

From 2008 to 2016, the world was captivated watching Usain Bolt win and sometimes break records with ease at the Olympics. The Jamaican sprinter was one of the biggest stars of the Summer Olympics, and next year’s Games in Tokyo will mark the first Olympics without him since 2000. Despite the presence of many others who are stars already or will soon become stars, Bolt’s absence will certainly be felt. He is practically irreplaceable, with regard to both his pure talent and the show that he provided on the Olympic stage.

Ashton Eaton accomplished everything he needed to in the sport. He won back-to-back Olympic gold medals (2012/2016) and back-to-back world titles (2013/2015), three world indoor titles and the two best decathlon scores at the time of his retirement in 2017. David Rudisha ran the most beautiful race to win the 2012 800-meter Olympic title in world record fashion, then ran his fastest time since the London victory to defend his Olympic title in 2016.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• IAAF World Championships: September 28- October 6, 2019 in Doha, Qatar

• U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials: February 29, 2020 in Atlanta

• U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials: June 19-28 in Eugene, Oregon

In order to compete at the 2020 Olympics, an athlete will need to finish within the top three of their respective events at the trials and meet the Olympic standards set by the IAAF.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

The next generation is here

Tokyo could be a proving ground for many rising stars and medal contenders.

In Rio, Sydney McLaughlin was the youngest athlete on the U.S. track team as a 400-hurdler. Since then, she graduated high school, attended Kentucky for a year to break the NCAA record in the event and claimed an individual national title. The 400-meter hurdles is one of the United States’ deepest events but if she can make the Olympic team, she will be in the medal conversation.

Noah Lyles has done a great job of replacing Bolt in regards to pre- and post-race antics. The 21-year-old gets creative with funky-patterned socks for his races and celebrates with the latest dance crazes or cartwheels. He can do that because he backs up his act with stunning sprint performances. In 2018, he went undefeated in the 200 meters.

Christian Coleman went from being a 4x100-meter relay runner for Team USA at the 2016 Olympics to claiming a silver medal behind Gatlin and ahead of Bolt at the 2017 world championships’ 100-meter final. He decided to bypass his senior year at Tennessee to turn pro for 2018.

If injuries continue to hamper Van Niekerk and he’s unable to return to 2016 form, Michael Norman should be the 400-meter favorite. He shattered the NCAA record for the 400 in his sophomore year before turning pro.

Lyles, Coleman and Norman could put together the first U.S. men’s gold medal sprint sweep since Gatlin, Shawn Crawford and Jeremy Wariner took gold in the 100, 200 and 400 at the 2004 Olympics in Athens.

Shelby Houlihan made the 2016 U.S. Olympic team in the 5,000 meters and then finished 11th in the Olympic final. Last year she won national titles at the 1,500 meters and 5,000 meters before setting the American record for the latter distance.

Will Caster Semenya be able to defend her title?

It remains uncertain whether Caster Semenya will be able to defend her world championship and Olympic gold medals as she fights the IAAF in court on new rules that would limit female runners’ testosterone levels. The South African star has been the most dominant 800-meter runner since 2016.

Doping bans

Russian track and field athletes were not eligible to compete in Rio, and the nation remains banned from international competition due to continued cases of widespread doping. In June, 33 Russian athletes were hit with doping allegations of using banned substances and treatment from a doctor. Kenya also continues to have doping issues, which were underscored by 2016 Olympic marathon gold medalist Jemima Sumgong testing positive for EPO and then being banned for eight years for lying to investigators.

More corruption

Former IAAF President Lamine Diack will stand trial in France for corruption charges.

—Chris Chavez

SWIMMING

FAMILIAR NAMES LIKELY COMING BACK

• Katie Ledecky

• Simone Manuel

• Nathan Adrian

• Lilly King

• Ryan Murphy

All five won gold medals in individual events in Rio de Janeiro. And those are just five names from a typically impressive, deep U.S. team. It may just not seem that way because…

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

• Michael Phelps

• Ryan Lochte

• Missy Franklin

• Connor Jaeger

• Maya DiRado

That Phelps guy: Perhaps you’ve heard of him. This will be the first Olympics since 1996 without Phelps, and the first since 2000 in which he is not the biggest American star. The Americans will miss Lochte less, especially out of the pool, where he managed to create (or fabricate) an international incident last time. Franklin starred in London but not in Rio.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• World Championships: July 12-28, 2019

• U.S. Olympic trials: June 21-28, 2020

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Filling a Phelps-sized hole

Swimming is the major story and major television attraction for the first week of the Olympics, and it usually gets the U.S. rolling in the medal count. Americans have become accustomed to dominating the swimming events, partly because the U.S. had the best swimmer ever. Without Phelps—who won five golds in Rio—the U.S. may cede a little ground in the medal count, but swimming remains an American strength.

To understand how long Phelps reigned: He made his Olympic debut in 2000 in Sydney. One candidate to be a breakout star for the U.S. in Tokyo, Regan Smith, was not even born until 2002. Smith is just one of several names you probably don’t know now but will next summer.

Caeleb Dressel won seven events at the 2017 World Championships in Budapest, and might win eight at the currently ongoing 2018 event. He will be 23 at the Tokyo Olympics. He won two golds in Rio, but both were in relays. With individual success in Tokyo, Dressel can become perhaps the biggest American star in Tokyo.

Rio’s breakout star keeps dominating

Then there is Ledecky, whose Q score has not quite matched her dominance in the pool, for reasons that are not entirely clear. She won three individual golds, a team gold and a team silver in Rio. She is universally admired. The trick with Ledecky is creating suspense. She won the 800 freestyle by more than 11 seconds, which is a lifetime in swimming, and the 400 free by nearly five. She also won the 200 free. Ledecky was, stunningly, upset in 400 free at the World Championships this week. She finished second to Australia’s Ariarne Titmus, her first time losing the event at a major international meet in six years. She then withdrew from two other events, citing an illness.

The IOC has added a women’s 1500 freestyle for Tokyo; it might as well have included, “Katie Ledecky will win the gold medal” in the press release. At the 2018 Pro Swim Series in Indianapolis, Ledecky took almost five seconds off her world-record 1500 time and finished almost 50 seconds ahead of everybody else. In the 1500 free in Tokyo, Ledecky can become the first swimmer to win gold, then grab a microphone and do play-by-play of everybody else in the race.

Best of the rest

If Ledecky’s dominance bores you, this is not her fault, and also: Go hang out with Lilly King for a while. King called out Russia’s Yulia Efimova in Rio for “drug cheating” and has taken shots at China’s Sun Yang as well.

King may make you feel righteous anger. Nathan Adrian might make you cry. Since Rio, Adrian has been diagnosed with testicular cancer. He has gamely kept training and recently posted a 48.50 time in the 100 freestyle. That’s almost a second off the gold-winning time in Rio, but it’s a sign that Adrian will contend for a medal again.

And if you just love to watch extremely tight races, then keep an eye on Simone Manuel and Canada’s Penny Oleksiak. They tied for gold in the 100 free in Rio, and one must admit: If they somehow tie for gold again, theirs would be one of the great rivalries in sports history.

—Michael Rosenberg

GYMNASTICS

FAMILIAR NAMES DEFINITELY COMING BACK

• Simone Biles

• Sam Mikulak

The International Gymnastics Federation voted to confirm a proposal in 2015 to change the size of Olympic gymnastics teams from five athletes to four, and the change will be enacted for the first time in Tokyo 2020. Presumably this means somebody will miss out, whether that’s an established veteran or an up-and-comer. But what we can definitively say is that the U.S. women will be led by four-time world champion Simone Biles, who has said this will be her last Olympics. Two-time Olympian Sam Mikulak will lead the men’s side.

FAMILIAR NAMES UNLIKELY TO COME BACK

• Aly Raisman

• Gabby Douglas

• Laurie Hernandez

While we’ve seen Biles continue to compete, the same can’t be said of her famous teammates from the Final Five from Rio. Aly Raisman, Gabby Douglas and Laurie Hernandez are all pretty much out of contention for Tokyo, barring unforeseen changes. In order to be a serious contender for the 2020 Games, athletes must compete at this year’s nationals in August, but there’s been no indication that they will.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• August 8-11, 2019: U.S. Gymnastics Championships in Kansas City, Mo.

• October 4-13, 2019: Worlds in Stuttgart, Germany

• June 25-28, 2020: U.S. Olympic Team Trials in St. Louis

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Ongoing USA Gymnastics scandal

Simone Biles killed it at the 2018 World Championships, winning six medals while competing with a kidney stone. Morgan Hurd and Sam Mikulak recently won all-around titles at the World Cup in Tokyo. On the surface, it may appear to be business as usual for USA Gymnastics. But as these athletes prepare for an Olympic year, things are very messy.

USA Gymnastics has struggled to move past the Larry Nassar sex abuse scandal in which the longtime team physician molested more than 350 girls and young women, including superstars like Biles, Douglas, Raisman and McKayla Maroney. The disgraced doctor, now in jail, has completely tarnished the USA Gymnastics brand. (As have the many people within the organization who were guilty of negligence, enabling Nassar, covering up or contributing in any way to this heinous scandal.) The federation lost all of its major sponsors, the U.S. Olympic Committee wants to decertify the federation as the sport’s governing body, and USA Gymnastics faces dozens of lawsuits from survivors. Not to mention it still deals—and perhaps always will—with ruthless criticism for fostering a culture of fear and silence that allowed Nassar to prey on athletes.

In February, Li Li Leung, the NBA’s vice president for global partnerships, became the fourth person in the last 23 months to be named the new president and CEO of USA Gymnastics. She’s committed to transforming the culture of one of the Olympics’ most popular sports, and believes her experience—both professionally and as a former gymnast—will help her do it. But she has a very lengthy and overwhelming to-do list.

Her immediate focus includes settling lawsuits and implementing recommendations from the Deborah Daniels report. Also on that list is meeting with survivors and current athletes. This includes the federation’s most powerful and marketable gymnast: 22-year-old Olympic champion and four-time world champion Simone Biles, whose voice has deeply impacted the future of the sport. One example of that happened in January 2018, before Nassar was sentenced. Biles tweeted a statement announcing that she, too, had been sexually assaulted by the former team doctor and couldn’t bear to think about returning to the facility where that abuse took place. Later that month, USA Gymnastics stopped holding camps at the Karolyi Ranch.

At one point, Biles said she didn’t even want to set foot in a gym. She sees a therapist to help her overcome those fears and reach her goals. When she and her teammates step out on the floor in Tokyo, it’ll be an incredibly emotional moment. This will be the first Olympics since the Nassar scandal; the first Olympics since these athletes bravely spoke out and began advocating for a more empowering culture.

—Laken Litman

BASKETBALL

MEN'S

FAMILIAR NAMES LIKELY COMING BACK

• James Harden

While USA Basketball ultimately picks the Olympic team from a pool of 35 players, the three players above all have Olympic gold medals already, and were invited to USA Basketball’s August 20-man training camp ahead of the 2019 FIBA World Cup in China. Harden and Davis both declined invitations—each is currently busy preparing for an NBA season next to a new superstar teammate—but taking the summer of 2019 off wouldn’t preclude them from rejoining the national team for 2020. It's made headlines this week that a lot of star players are pulling out for this summer, but that figures to change when the obligation comes with an actual trip to the Olympics. The two other former gold medalists who were invited to the FIBA camp are Kevin Love and Harrison Barnes.

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

• Carmelo Anthony

Alas, the legend of Olympic Melo ended in Rio. Carmelo Anthony retired from international competition after his third gold medal in 2016—becoming the first American man to win three gold medals in basketball (and the first with four medals total). Melo finished his Olympic career first in several categories in the USA record books, including but not limited to games played, points, rebounds, and field goals.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• August 5–9, 2019: Training camp in Las Vegas for 20 finalists for FIBA World Cup

• August 13–16, 2019: Training camp resumes in Los Angeles

• August 17, 2019: 12-man roster for 2019 FIBA World Cup selected

• August 22, 2019: USA vs. Australia exhibition

• August 24, 2019: USA vs. Australia exhibition

• August 26, 2019: USA vs. Canada exhibition

• August 31–September 15, 2019: FIBA Basketball World Cup

• (Likely) June 2020: 12-man roster for 2020 World Cup selected

• July 2020: Training camp for Tokyo Olympics

In 2016, USA Basketball announced its 12-man roster a little over one month before the Games, and then held training camp roughly two weeks before the start of competition. Following a similar schedule, the Tokyo roster will be announced next June, with camp taking place in early July.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Coach Pop

There are a few big storylines to keep an eye on in the following year. First, some have speculated that coach Gregg Popovich could retire from coaching basketball altogether after the 2020 Games. The private Popovich likely won’t reveal his intentions during the NBA season, but it’s worth keeping an eye on the Spurs’ success and any comments Pop makes about his future over the next 12 months. Popovich is widely beloved by players around the NBA, and is arguably the best coach in the history of the sport. His swan song coming in the Olympics, considering San Antonio’s embrace of international players and Popovich’s standing as a steward of the sport of basketball, makes narrative sense.

Injured stars

Injuries will be a factor in who is ultimately selected for the 2020 Games. Once a shoo-in, it’s unclear what Kevin Durant’s status will be as he spends the next year recovering from the Achilles injury he suffered in the 2019 NBA Finals. If Durant sits out the next season with the Nets, will he be comfortable returning to competitive basketball in the Olympics? The same can be said for his former teammate Klay Thompson, who will likely return from a torn ACL during the upcoming season. But it’s possible Thompson will opt to rest next summer as opposed to pushing through on his knee.

Will rising stars step in for vets?

If veterans and older players do start dropping out, Popovich can always buttress the team with youth. Some of the players named to the 2018–20 35-man roster seem like longshots for Tokyo—guys like Isaiah Thomas, Eric Gordon, John Wall, and Chris Paul, for various reasons, seem unlikely to be picked for 2020. Meanwhile, Jayson Tatum and Kyle Kuzma were among those invited to camp ahead of Vegas. And what if Zion Williamson lives up to every ounce of the hype during his first year as a pro? A next generation of American stars is waiting in the wings, and it’s possible that group breaks through sooner rather than later.

Of course, all basketball roads lead back to LeBron James. LeBron’s Lakers are expected to make a deep playoff run in 2020, and that team now includes fellow Olympian Anthony Davis. While Finals trips haven’t stopped James from playing in the Olympics before, he will be 35 years old by the Tokyo Games. Basically, a grueling championship run for Los Angeles could give multiple players some hesitation in participating next summer.

For any big names on the fence, however, the IOC’s new basketball group structure could push them toward participating. FIBA has introduced a new format for the group stage at the Olympics, separating the 12 teams into three groups instead of two. This means teams will play only three games before the knockout stage as opposed to five, and only six games total will be needed to win a medal. FIBA said it made the changes explicitly to reduce the workload of the players.

(Also, while three-on-three basketball will be introduced at the 2020 Games, those teams will be selected from a different pool of players. So any dreams of seeing Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson, and Kevin Durant run it back will have to wait until Ice Cube’s BIG3 league.)

Top competition for Team USA

As far as the biggest competition for the U.S. men’s team, old foe Spain (which won silver in 2008 and 2012, and bronze in 2016) is ranked second in the current World Cup qualifying window. NBAers who could potentially compete for Spain in Tokyo include Marc Gasol, Ricky Rubio, and the Hernangomez brothers Willy and Juan. Canada, despite all its recent influx of NBA talent, is currently No. 23 in the FIBA rankings.

WOMEN’S

FAMILIAR NAMES LIKELY COMING BACK

• Breanna Stewart

• Tina Charles

• Brittney Griner

• Elena Delle Donne

Charles, Griner, and Delle Donne were all members of the 2018 FIBA World Cup team as well as the 2016 squad that captured gold in Rio. The same is true for Stewart, who is expected to play in Tokyo even after tearing her Achilles, causing her to miss the 2019 WNBA season.

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

• Tamika Catchings

• Lindsay Whalen

• Candace Parker

Catchings and Whalen have both retired from basketball since the 2016 Games. Catchings won four Olympic gold medals during her international career, which began with USA basketball in 1996 on the under-18 team in the Junior World Championship. Whalen, a two-time gold medalist, is currently the head coach at the University of Minnesota. She retired from international play after Rio, and ended her professional career after the 2018 WNBA season.

Parker was controversially left off the national team in 2016. There was some hope she would return to the squad after Dawn Staley was named coach, but Parker declined an invitation to the initial training camp for this Olympic cycle, and said in April 2018 she would not play for the national team anymore after how her non-selection for Rio was handled.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• September 21–29, 2019: FIBA AmeriCup in Puerto Rico

• November 10–18, 2019: FIBA Olympic Pre-Qualifying Tournament

• February 2–10, 2020: FIBA Olympic Pre-Qualifying Tournament

• (Likely) April 2020: 12-woman roster selected for Tokyo

USA has already qualified for the 2020 Games, but will still participate in the upcoming qualifying tournaments for experience, according to Staley and national team director Carol Callan.

“One of the good byproducts of this system is instead of us always trying to manufacture training camps and practice, we now have competitions where there is a purpose for coming together,” Callan said in a press release in April. “We think that will be much better for our players, rather than trying to find two or three practice days a couple times a year.”

There is no official date for when the 2020 team will be announced. Before the 2016 Games, the roster was revealed in late April.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Will a few icons return to the court?

The biggest question for Tokyo that will be answered over the next year is whether or not Sue Bird and Diana Taurasi will suit up for their record fifth Olympics. Both Bird and Taurasi were on the 2018 FIBA World Cup team, and both have left the door open for a return in 2020. The basketball icons have won four gold medals with the national team, and both were actually teammates of coach Dawn Staley’s at the 2004 Olympics in Athens. When she was named coach of the national team in 2017, Staley said her gut feeling was that Bird and Taurasi would participate in 2020.

Bird, 38, who is also a basketball operations associate for the NBA’s Denver Nuggets, has missed all of the ongoing 2019 WNBA season after undergoing knee surgery earlier this year. Taurasi, who will by 38 by the start of the 2020 Games, has also missed all of the current WNBA season after undergoing back surgery, though she is expected to return soon.

Maya Moore, who is sitting out the current WNBA season to focus on social justice issues, is still part of the player pool for Tokyo if she chooses to return to basketball by then. Moore, 30, announced in February she would step away from basketball to focus on off-court issues. In a story in The New York Times, Moore revealed she will spend part of her sabbatical trying to help free a man she believes was wrongly convicted of burglary and assault.

New faces

Meanwhile, there should be plenty of new faces to emerge over the next year who will likely begin their own gold-medal streak. A’ja Wilson, Jewell Loyd, Kelsey Plum, and Morgan Tuck were all part of the 2018 FIBA team, and other 20-somethings in the Tokyo player pool include Chiney Ogwumike, Brittney Sykes, and Asia Durr. If the likes of Bird, Taurasi, and Moore do eventually sit out the 2020 Games, there are numerous young stars in the WNBA who seem primed to take their place.

Whoever does end up on the Tokyo roster, dominance is the expectation. Staley, a three-time gold medalist herself, will be attempting to continue a gold medal streak that dates back to the 1996 Atlanta Games. USA Basketball has won eight of 10 Olympic competitions, and seven of the last 10 FIBA World Cups. The last national team to fail to win gold was the 1992 squad in Barcelona.

—Rohan Nadkarni

SOCCER

MEN’S

QUALIFIED TEAMS

The U.S. men haven’t qualified for the Olympics since 2008, and that will be the main goal this year for coach Jason Kreis and his team. On the men’s side, the Olympics is an under-23 tournament—with the cutoff being players born on or after January 1, 1997—that also allows three overage players per team to add some star power.

We already know five of the 16 teams that will play in the Olympics: Host Japan, France, Germany, Romania and Spain (which were the top four finishers in the recent UEFA Under-21 championship). The rest of the spots will go to CONCACAF (two), Oceania (one), Africa (three), Asia (three) and CONMEBOL (two).

STATUS OF FAMILIAR NAMES

There will usually be a few big names in the Olympic men’s tournament, which is what we saw in 2016 when a team with Neymar, Alisson and Gabriel Jesus led Brazil to the first Olympic soccer gold medal in the country’s history. But it’s always a challenge for top stars to participate, not least because clubs are not required to release their players for an age-group tournament.

In the case of Japan, you can safely assume the hosts will want to do well and try to bring as strong a team as possible. Spain’s standout player as it won the UEFA U-21 championship was Fabián of Napoli. Germany’s runner-up team included Maximilian Eggestein of Werder Bremen and Mahmoud Dahoud of Borussia Dortmund. France included Arsenal’s Mattéo Guendouzi.

As for the U.S., senior national team players Christian Pulisic, Tyler Adams and Weston McKennie are all age-eligible, so the possibility exists that they could play for the U.S. in Japan if the Americans qualify. But there’s very little chance that they would be released to be part of the CONCACAF Olympic qualifying tournament.

U.S. players that could be available for qualifying—especially if at least part of the CONCACAF qualifying tournament takes place during an international window—include Tim Weah, Josh Sargent, Erik Palmer-Brown, Cameron Carter-Vickers, Antonee Robinson, Sebastián Soto and Paxton Pomykal. A large contingent of MLS-based young players is also expected to be involved in qualifying.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• Oceania Olympic Qualifying Tournament: September 21–October 5, 2019

• CONCACAF Olympic Qualifying Tournament: Fall 2019

• Africa U-23 Cup of Nations: November 8-22, 2019

• Asian U-23 Championship: January 8-26, 2020

• CONMEBOL Pre-Olympic Tournament: January 15–February 2, 2020

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Can the U.S. finally qualify again?

Failures under coach Caleb Porter (for 2012) and Andi Herzog (for 2016) meant the U.S. players missed good opportunities to play in international tournaments that could help prepare them for standing out at the senior level. Kreis, who won the MLS Cup in 2009 with Real Salt Lake, used to be seen as a favorite to coach the U.S. senior team someday, but his standing has fallen after unsuccessful stints coaching NYCFC and Orlando City. Can he get back on the star track with a qualification and good performance in Japan?

The defending champs

How will Brazil view the men’s tournament now that it finally won a gold medal? For decades, the Olympic gold was the only soccer prize that had eluded Brazil, which was thus willing to devote a lot of star power to the cause of ending the misery. That finally happened in 2016, so you have to wonder how seriously Brazil (if it qualifies) will take the Olympics this time around in terms of the players it sends.

Impact of other tournaments

How will Euro 2020 and the 2020 Copa América—the fourth Copa América in six years!—influence roster decisions and fan interest in the Olympics? Both marquee tournaments will end on July 12, just 11 days before the start of the men’s Olympic tournament. It seems unlikely that we’ll see any players try to compete in both tournaments, which isn’t a wise idea anyway. And how much will fans even care about an age-group Olympic tournament once they’ve been subjected to wall-to-wall Euro and Copa América coverage?

WOMEN’S

QUALIFIED TEAMS

Unlike the women’s World Cup (which has 24 teams) or the men’s Olympic soccer tournament (which has 16), the women’s Olympic soccer tournament will still have just 12 teams in 2020—a sign that the IOC doesn’t think women’s soccer is as important as the men’s game. That’s a problem, obviously, especially when the women’s Olympic tournament has the best women’s players, regardless of age, while the men’s game is an under-23 tournament (with three overage players allowed per team).

We already know six of the 12 teams that will play in the Olympics: Host Japan, Brazil, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Sweden and Great Britain (which will be a combined team of players from England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). UEFA awards its three Olympic spots to the top three European finishers at the World Cup, which means powerhouses Germany and France (which lost in the quarterfinals) will not be competing in Japan.

The World Cup champion U.S. is expected to have no trouble earning one of the two spots from CONCACAF at an Olympic qualifying tournament expected in early 2020. The other four tournament berths will come from Asia (two), Africa (one) and the winner of a playoff between Chile and the second-place team from African qualifying.

STATUS OF FAMILIAR NAMES

We have yet to hear of international retirements by any of the biggest stars in the women’s game following the World Cup. That’s not surprising, since there’s only one year between tournaments. Brazil’s Marta, the six-time world player of the year, has said she isn’t sure yet if she will continue with her national team for the Olympics, but at least she knows her team will be there.

Olympic rosters have just 18 players, five fewer than the 23 for the World Cup. So that means it could be unlikely we’ll see World Cup 2019 winners Ashlyn Harris, Ali Krieger, Allie Long or Jessica McDonald—all of them reserves, all of them in their 30s—on the U.S. Olympic team.

It’s also possible that a U.S. star or two might decide to go out on top—Lauren Holiday and Abby Wambach announced their retirements after winning the 2015 World Cup—and some stars who may want to extend their careers might be on the bubble to make the Olympic roster. It will be interesting to see what happens with Carli Lloyd, who will be 38 during the Olympics.

Then there’s two-time World Cup-winning U.S. coach Jill Ellis. Her contract expires on July 31, 2019, but U.S. Soccer has a one-year option to extend Ellis through the Olympics if the federation and Ellis were to agree on that. A lot remains to be decided at U.S. Soccer: A new CEO and the first women’s GM (who will be in charge of hiring and firing the coach) are expected to be named soon.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

• CONCACAF Olympic Qualifying Tournament: Early 2020

• African Olympic Qualifying Tournament: January 13 - February 9, 2020

• Asian Olympic Qualifying Tournament: March 2-11, 2020

• African-South American Playoff: 2020

STORYLINES TO WATCH

U.S. motivation

If the U.S. is looking for some motivation, here’s some: No team has ever won the women’s World Cup and then gone on to win the Olympic gold medal the following year. In the past, U.S. players have talked about the difficulty to stay focused after winning a World Cup with all the media attention and endorsement opportunities, to say nothing of the natural letdown on the field that comes after winning a World Cup.

Hungry host nation

Japan has a young team that will be gunning to win an Olympic gold medal on home soil. The Japanese reached the finals of the 2011 World Cup (winning it), the ’12 Olympics and the ’15 World Cup. Nadeshiko didn’t go as far in World Cup 2019, but they improved as the tournament went on and were unfortunate to go out in a thrilling Round of 16 game against the Netherlands.

Rising U.S. stars

Will U.S. winger Mallory Pugh finally make the leap? Pugh will be 22 at the Olympics, but after making an impact as an 18-year-old in the 2016 Games, she took a step backward at World Cup 2019, playing less and less as the tournament progressed. It won’t be easy breaking into the starting lineup, considering Tobin Heath (and Megan Rapinoe on the other side) will try to hold onto their starting jobs.

Is Rose Lavelle on her way to becoming the world’s best player? Lavelle, who will be 25 in Japan, was the breakout star of the World Cup and with her overflowing attacking skills could be on a rocket ride to the top of the women’s game by the time the Olympics hit. The biggest concern about Lavelle may be her propensity for injuries. But when she’s healthy, she’s a force, and we’re only starting to see it fully.

Any challengers?

Can anyone challenge the Americans? The U.S. performance at the World Cup was absolutely dominant, and we already know France and Germany won’t be at the Olympics to provide a challenge. The most likely candidates to give the U.S. a tough time will be Great Britain, the Netherlands and old nemesis Sweden. But there’s a clear gap in talent there between the U.S. and those teams based on what we saw at France 2019.

—Grant Wahl

GOLF

FAMILIAR NAMES COMING BACK

We can’t really call anyone a sure thing for the Olympics because the qualification process is entirely determined by the world rankings on June 22, 2020 (the day after the men’s U.S. Open). The guidelines are as follows, and are the same for both men and women: Sixty players will tee it up in each tournament. The top 15 players in the world all qualify, though a maximum of four players from one country can qualify this way (this limit will likely only apply to American men, and American and Korean women). The remaining spots will go to the highest-ranked players from countries that do not already have two golfers qualified.

If forced to pick a player who will be back: Justin Rose is a solid bet to defend his gold medal. He’s the No. 4 player in the world and the top-ranked Brit. But Matt Kuchar, the silver medalist in 2016, would not qualify today despite being world No. 16, because there are 10 Americans ranked higher than him.

One of those Americans is Tiger Woods, who at world No. 5 would be in. There are very, very few things Tiger Woods has not won in golf, but an Olympic medal is one of them.

On the women’s side, the gold medalist from 2016 (Inbee Park, Korea), the silver medalist (Lydia Ko, New Zealand) and the bronze medalist (Shanshan Feng, China) all would qualify as of right now. The American contingent would be Lexi Thompson (who played in 2016), Nelly Korda, Danielle Kang and Jessica Korda.

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

Again, it is virtually impossible to predict what the world rankings will look like in a year, and who actually competes in the event will be heavily influenced by how many players decline to play.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

Because the qualification process is entirely decided by the world rankings, the major tournaments—which offer the most world ranking points—between now and June 22 will be the most impactful.

MEN:

• Masters: April 9-12, 2020

• PGA Championship: May 14-17, 2020

• U.S. Open: June 18-21, 2020

WOMEN:

• Evian Championship: July 25-28, 2019

• British Open: August 1-4, 2019

• ANA Inspiration: April 5, 2020

• U.S. Women’s Open: June 4-7, 2020

The world rankings that will be used to determine the contestants will be those of Monday, June 22 (before The Open Championship and the KPMG Women’s PGA Championship).

You can keep an eye on the men’s and women’s rankings throughout the year.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Will the schedule changes prompt more elite men to play?

Four years ago, golf made its return to the Olympics after a 112-year hiatus. It would have been a triumphant affair had so many of the world’s best players not skipped the event. The top four players in the men’s world rankings at the time—Jordan Spieth, Jason Day, Rory McIlroy and Dustin Johnson—all declined to play and all pointed to Zika virus concerns. But the real reasons they, and many other players, skipped were simple scheduling inconvenience and a lack of prize money.

Summers are always jam-packed for golf, but 2016 was especially crowded—the Rio golf tournament came just two weeks before the FedEx Cup playoffs began and two weeks after the PGA Championship (which moved up from its normal August spot that year to accommodate)…which came just two weeks after the British Open…which came just two weeks after a World Golf Championship…which came just two weeks after the U.S. Open. A number of players decided they’d rather use the time between the PGA and the FedEx Cup playoffs to rest up rather than play in the Olympics for free. Make of that what you will, and know that some of those players expressed regret about missing out almost immediately.

Changes have been made. The PGA Championship has been permanently moved from August to May. The FedEx Cup playoffs have been shortened from four events to three. There is a much more defined offseason now. And, it should be noted, there is no disease excuse to use as a crutch. All this should lead to a better field, but superstar PGA Tour players are a fickle bunch and they’re used to playing in tournaments that offer $10+ million in prize money. Will they add another event to their schedule, in the dog days of summer, for free?

Tiger watch

If you’re a tournament organizer, here’s the first question you ask yourself: Is Tiger Woods playing? His presence singlehandedly elevates the status of any golf tournament. The same holds true for the Olympic golf tournament. The 2016 event was plagued by a dearth of star power, and there is no bigger star than Woods. He plays a remarkably limited schedule these days, but he has said he would like to represent the United States on that stage. It would be quite poetic, as well, as Woods is such a key reason golf became a global enough sport for the IOC to bring it back after 112 years.

Because there are so many great American golfers, if Woods is eligible in one year’s time, it will mean he’s still playing at an elite level. That’s far from a guarantee, given the depth of competition and his well-publicized injury history. But if he does qualify, and he does play, seeing Tiger Woods in the Olympic Opening Ceremony will be quite the sight.

Diversity in the women’s field

The nationality of the top women’s players has been in the news for the wrong reasons. Hank Haney, Tiger Woods’ former coach, made racially insensitive comments ahead of the U.S. Women’s Open. He said he couldn’t name four players on the LPGA Tour, then said he could if he could just guess “Lee,” a crass commentary on the prevalence of Korean players atop the women’s game. The Olympic qualification formula—namely, capping each country to a maximum of four players—is designed to ensure a diverse field. As was the case in 2016, the Olympics will be a welcomed platform for many women, from many different corners of the world, to compete on the global stage.

—Daniel Rapaport

TENNIS

STATUS OF FAMILIAR NAMES

Tennis has its four annual majors, the events that make up the Grand Slam, but every four years the Olympic tennis event takes on the status of a fifth Major. Virtually every eligible player will enter.

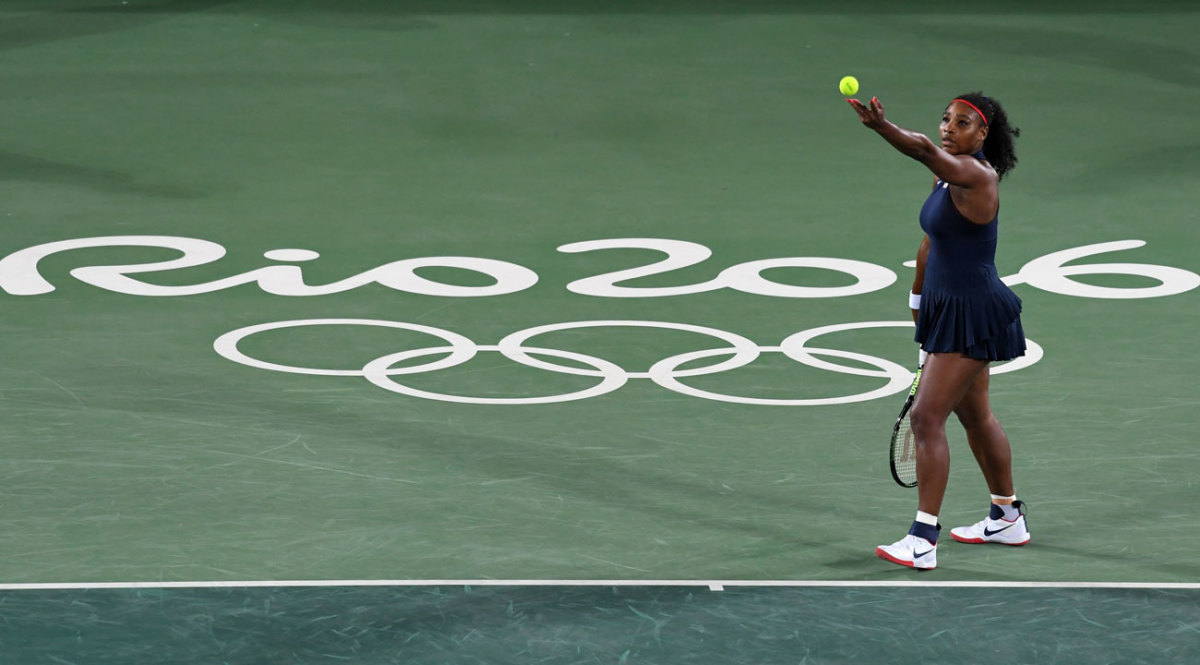

A year out, a lot can change. But if the 2020 Olympics were held today, every star—from Serena Williams to Roger Federer to Rafa Nadal—would happily be playing in the singles draw. And many would try to increase their medal chances by entering doubles and mixed doubles, as well. That the Games will be in Tokyo, after Wimbledon and just before the 2020 U.S. Open in New York? Not ideal. But expect most stars to make the effort.

There will be some omissions, but only because each country can send a maximum of four singles players. For instance, as it stands today, one player among Serena Williams, Venus Williams, Sloane Stephens, Madison Keys, and Amanda Anisimova would likely be out of luck and fail to gain a roster spot on the American team. At least in singles.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

Qualification will be determined by the ATP and WTA ranking lists on June 8, 2020.

The ATP and WTA pro tennis calendars will proceed apace. There will be five major events in tennis (and a new all-comers format Davis Cup team competition) between now and Tokyo. But unlike in other sports, the calendar does not change to accommodate the Olympics or create qualifications.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Everyone wants to be there

For all the feuds and cleavages in tennis, here is a statement that will lead to some common ground: The Olympic tennis event is fantastic. All of tennis’s virtues are on vivid display—its star power, its international cast, its seamless positioning of men and women alongside each other. Since tennis made its return to a medal sport in 1988 in Seoul, it’s become a must-attend gala for even the brightest stars and the most road-weary players. Ask Roger Federer to enumerate his few career disappointments, and the lack of singles gold tops the list. Ask players like Rafa Nadal, Andy Murray and Serena Williams to catalog their highlights and their successes, and winning a gold medal ranks up there with the Wimbledon crowns and other major titles.

The Olympics are held in such high esteem that multiple stars still currently playing deep and into their 30s are using the motivation of Tokyo 2020 as a potential career finish line. For Serena Williams—one of the members of this cohort—she would be playing in her sixth Olympics, having first competed in Sydney in 2000 (where she won gold in doubles, paired with her sister, Venus).

Truth be told, for the stars, there are commercial inducements as well. Nike will want all of its athletes to play in the Olympics, a far bigger global stage than tennis’s run-of-the-mill tournaments. Roger Federer left his Nike apparel deal for Uniqlo. To traffic in understatement, a Japanese manufacturer will expect its highest-paid athlete to make an appearance in the Tokyo Games.

The homegrown star

As we write this, the No. 2 player in the women’s game—and recent No. 1—is Naomi Osaka. Though she resides in the U.S., she plays for Japan. (And is surely the only player to share a surname with her birthplace.) Having won both the 2018 U.S. Open—taking down the mighty Serena Williams in the final—and the 2019 Australian Open, she is a mega-star in Japan. Having such a prominent homegrown medal contender will only increase attention on the tennis event in Tokyo.

Osaka’s presence, along with several legends of the sport potentially playing the final major event of their careers, has the potential to make tennis an exceedingly important event at the 2020 Games.

—Jon Wertheim

BASEBALL/SOFTBALL

BASEBALL

STATUS OF FAMILIAR NAMES

This one is a little different from the other sports on this list. No names are coming back from Rio, because there was no Olympic baseball in 2016. Or in 2012.

Baseball is returning to the Olympics for the first time since 2008, but despite the hiatus, there are some big names from the last go-round who are still active. Korea, which won gold in Beijing, featured a 21-year-old Hyun-jin Ryu, five years before he’d debut in MLB. Cuba’s silver medalists included current Houston Astro Yuli Gurriel. And Team USA’s bronze-medal group had Stephen Strasburg (in college), Jake Arrieta (High-A), and Dexter Fowler (Double-A). Notably, of course, none of those players were in MLB… because they couldn’t have been, given the scheduling. In 2008, spots were only given to players not on a team’s 40-man roster.

MLB hasn’t officially announced whether big-league players will participate in 2020, but it seems unlikely, given past precedent, and Team USA, at least, has announced that on its roster for the qualifying games, “preference will be given to those players not on the 40-man rosters of the 30 MLB teams.” In other words? Don’t expect recognizable names from the big leagues, and certainly don’t expect returning players from the Olympic rosters in 2008. (No Strasburg vs. Ryu showdown for a medal, alas.) Instead, get ready for some prospects.

From Japan, on the other hand, look for their very best. Nippon Professional Baseball will be briefly suspended to accommodate the Olympics. It’s a sign of how seriously Japan is taking this portion of the Games, which was probably already evident—baseball and softball were two of the sports added for 2020, with no promise to return for 2024, under the new provision that the host country can nominate locally popular sports for inclusion. Baseball is here because Japan wanted it to be, and this might be its last time in the Olympic spotlight for a while.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

The Games will include six teams; Japan, as the host country, is the only nation with a guaranteed spot. To determine the other five, qualifying matches will be broken up by continental groups. First, in September, Europe and Africa will compete for one spot. Then, in November, a twelve-team tournament will be held to reserve two berths, one for the top team from the Americas and one for the top team from Asia or Oceania. (Team USA’s first game will be with this group, on November 2.) An Americas-only qualifier in March 2020 will give another spot to the top remaining team from the Americas, and there will be one additional qualifier to present the last spot to the best of the remaining global teams.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

Comparisons to other international competitions

How different will Olympic baseball feel now from how it did when we last saw it? The last decade has held some pretty major changes for international competition. In 2008, the World Baseball Classic was only just getting off the ground—the tournament had then been held only once, in 2006. At the time, Olympic baseball was international baseball, because there was simply no other established model for how the game might look on a global stage. Now, though? The WBC has grown and demonstrated just how great international baseball can be, with a schedule that allows for easy participation from MLB (and NPB, KBO and Serie Nacional). The most recent versions of the tournament have shown off great venues that encourage plenty of fan interaction, with a generally loose and fun vibe. And with 16 qualifying teams, there’s room for intriguing underdog stories, like Australia and Italy.

Olympic baseball, by comparison, will be smaller. The limit of six teams will likely keep the field to traditional heavyweights, it will lack elite players from MLB and it will come at an already crowded point in the baseball calendar. Of course, in broad strokes, these have always been problems for baseball in the Olympics…except it used to have the saving grace of being the only opportunity for serious international baseball competition. Now, that’s gone, and there might be less motivation for top players to participate.

Who actually will play?

The big thing to keep an eye on, then, is what exactly these rosters will look like. “Not MLB players” leaves a lot of space for potential variety. Will top prospects be made available? Or will organizations guard their health and development too closely to send them to a large international competition in the middle of the season? Will any level of prospect be on the table? Will college players have to play a key role instead? (MLB’s choices here won’t just shape Team USA: Canada, the Domincan Republic and Venezuela, among others, also stand to be deeply affected.)

The tournament isn’t very long, so injury concerns might not be front-and-center. There’s a group round—in which the field will be broken down into two groups of three teams, round-robin style, meaning that each team will play two games—followed by a knockout round, in which each team will get to play at least one game and can qualify for as many as three, including the final. In other words, no team will play more than five games, and it seems unlikely that any one pitcher would be asked to make more than two starts. (There are 9 days between the first game of the group round and the final gold medal match-up, so there’s a little bit of time off built into the schedule, but not very much.) Even if the workload isn’t particularly heavy, though, teams tend to guard prospects’ development so closely that participation might still be ruled out for top names.

Essentially, baseball players and clubs have less incentive than ever before to want to be part of the Olympics, and seeing how these rosters shape up for the qualifying tournaments will reveal a lot about the type of baseball we’ll see in Tokyo in 2020.

SOFTBALL

FAMILIAR NAMES COMING BACK

Softball, like baseball, is coming back to the Olympics after being absent in 2012 and 2016. Unlike baseball, however, Team USA might include some players making their return from last time. 36-year-old pitcher Cat Osterman and 34-year-old pitcher Monica Abbott were teammates in the 2008 Olympics, and both are currently on the national team, poised to remain there for 2020. And if you’re looking for a fresh face you might recognize, if you watched this year’s Women’s College World Series, you probably remember UCLA’s Rachel Garcia—who sent her team to the championship with 10 scoreless innings (16 strikeouts, 179 pitches), before hitting the walk-off home run herself. She should be here, too.

FAMILIAR NAMES NOT COMING BACK

That 2008 team also featured Jessica Mendoza, who’s now busy with other endeavors.

KEY DATES BETWEEN NOW AND TOKYO 2020

Team USA has already qualified, by winning the 2018 Women’s Softball World Championship, and Japan has an automatic berth as the host country. This leaves four open spaces, to be determined through three qualifying tournaments held in July, August, and September.

Team USA will have at least two major competitions to get ready before 2020: The Pan American Games in August, and the Japan Cup in September.

STORYLINES TO WATCH

A rivalry renewed

The last Olympic softball game was a thriller. Team USA entered the 2008 gold-medal contest with a 22-game winning streak, stretching all the way back to 2000; it had won every single previous gold in softball, and 2008 looked like it would be no different. The U.S. was dominant throughout the tournament, outscoring its opponents 57-2. But Japan ultimately came through with a shocking upset in the final—ending the winning streak and taking the gold. Even 12 years later, with most players retired from both sides, that’s not the sort of thing that a country forgets, and it sets the stage for a riveting rematch between the two countries, now on Japan’s home turf.

These teams are about as closely matched as they can be. (Several American players go overseas to compete in the Japan Softball League, too, creating plenty of non-national team interaction between the two countries.) In last year’s Women’s Softball World Championship, Team USA earned its Olympic berth by defeating Japan twice: 4-3 in the semifinal, and 7-6 in 10 innings in the final. They’re that kind of closely matched. So a crucial event to watch out for in the run-up to 2020 is the Japan Cup, which begins August 30, and should be the last opportunity to see Team USA face Japan before the Olympics. Whoever wins there will likely set the tone—and the drive for revenge—between the two heavyweights for Tokyo.

And it’s worth noting here that Olympic softball’s format is a bit different from baseball. It’s a single round-robin, with each team playing every other one time, followed by the bronze and gold medal games. So if all goes as expected, USA and Japan will play twice—once in the round robin, once for the gold.

—Emma Baccellieri