Lessons from the Olympics Helped Shannon Miller Fight Ovarian Cancer

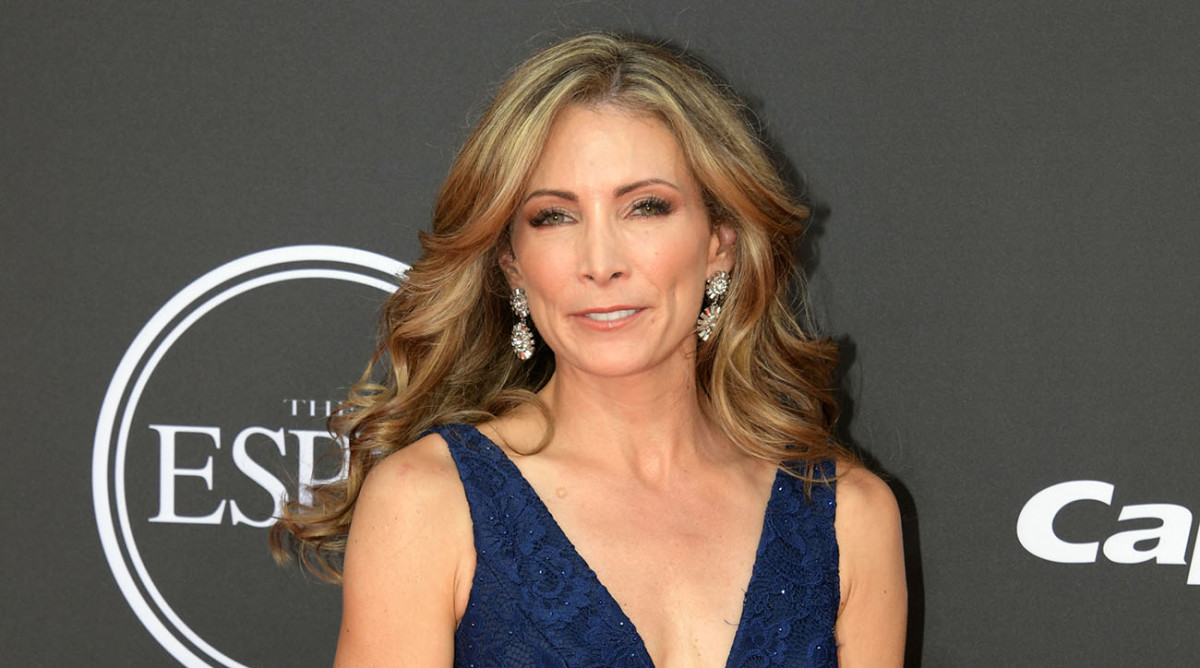

Shannon Miller walked into a routine appointment in late 2010 and told her physician that she “felt great.” Fifteen minutes later, Miller’s doctor found a baseball-sized mass on her left ovary.

Even to her, it came as a surprise. “Looking back, I think I probably should have been more aware of the signs and symptoms I was having,” the 43-year-old says. “Three primary symptoms that I was having that I didn’t even recognize as a potential signal for ovarian cancer, things like bloating, severe stomachaches, weight loss. I thought I was just losing baby weight after having my son.”

She had surgery to remove the mass in January 2011 and it wasn’t until she woke up from the procedure that she was given her diagnosis. In Miller’s case, they had caught the disease early and her prognosis was good. Her doctor already had a plan for an aggressive chemotherapy regimen that would provide the best chance of non-recurrence. Miller, who was 33 when she received her diagnosis, used some of the lessons from her gymnastics career in visualization, goal setting and teamwork and applied them to how she approached treatment.

“I think at that point is when I reverted back to that competitive mindset that I knew so well through sport,” she says. “I felt like I could wake up each day and have control over something, no matter how small. Maybe it was: Could I walk around the dining room table? I may have been an Olympic medalist, but at that moment if I could get up and walk around the dining room table, that was a win.”

Another lesson that Miller took from her gymnastics career was that there would be good days and bad days throughout her treatment process.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, you’re going to have bad days. And sometimes you’re going to need that pity party and you’re going to need to cry or yell and that’s fine. But then how do I take that next forward step, how do I get back up and I think that’s what gymnastics really taught me was you fall nine times, you get up 10.”

In 2017, Miller became involved with Our Way Forward, a program that serves as a call to action for not only ovarian cancer patients, but also their families and healthcare providers. The program provides a platform to share and hear stories from other ovarian cancer patients and healthcare partner—something that Miller, a mom of two, wishes she had access to throughout her diagnosis and treatment.

“If you read stories or listen to stories, it helps you realize you are not in this alone. It also helps with understanding some of the ways that you can get help and feel better,” she says. “I didn’t realize that I could speak up and say, I’m really nauseous, can we try something else because whatever we’re doing is not working. I didn’t want to bother anyone, I didn’t want to put anyone out, I didn’t want to complain so I just dealt with it.

"It wasn’t until weeks later that a nurse came and said, You don’t seem to be doing very well on this, do you want to try something else?”

For Miller, the days and weeks following her final treatment were among the most difficult. There was an expectation that she placed on herself that she should be back to being 100% as a mom, at work and everywhere in between. Her final day of treatment was something that she had built up in her head as being an ending, rather than an ongoing process that would continue in the months and even years afterwards.

“We really do need to have that community and that safe landing spot for those who are continuing to deal with some of the issues and anxiety every time you go in to get tested,” she says. “I still get tested twice a year and there’s still tough days. For the most part I’m doing well and feel fantastic and have no complaints. But testing days can bring anxiety. Every time you get a stomach ache, you have to wonder: Did it come back? And that can get really difficult.”

It was also a matter of feeling very alone in the aftermath of her treatment.

“I almost think in many ways the day you stop treatment is one of the toughest moments because you feel suddenly alone. I know that I did,” Miller says. “You go from being surrounded by nurses and doctors and friends and family and neighbors and coworkers with everyone pitching in to help out. You can feel very alone because all of that extra help tends to drop off.”

Miller celebrated nine years of being cancer-free in June, just a couple of months before the Tokyo Olympics were scheduled to begin. Miller is the most decorated American gymnast at the Olympic Games—she was the first U.S. gymnast to become Olympic champion on the balance beam when she won the first individual Olympic gold medal of her career at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. She and the rest of the Magnificent Seven made history days earlier when they earned the first team gold for the United States. The Oklahoma native earned five medals in Barcelona at the 1992 Games including a silver medal in the all-around by the slimmest of margins—12 one-thousandths of a point.

Gymnastics is often a fickle sport, where even what year an athlete is born can play a role in her chances of making an Olympic team and peaking at the right time. When the Games were postponed earlier this year due to COVID-19, even the most carefully crafted training plans were halted. But for some athletes, the postponed Olympics have provided them another chance.

“They’ve planned the last two years for peaking at exactly this past summer. So now they’re rerouting their plans but it is interesting because the postponement does help some athletes,” Miller says. “It is interesting for those athletes who maybe weren’t going to have the opportunity this year because of some other obstacle they were facing whether it was injury or timing or whatnot. They have this new opportunity.

"We’ve got Chellsie Memmel who is now going to vie for a spot next year and is making a comeback after having two children. So she’s my inspiration.”