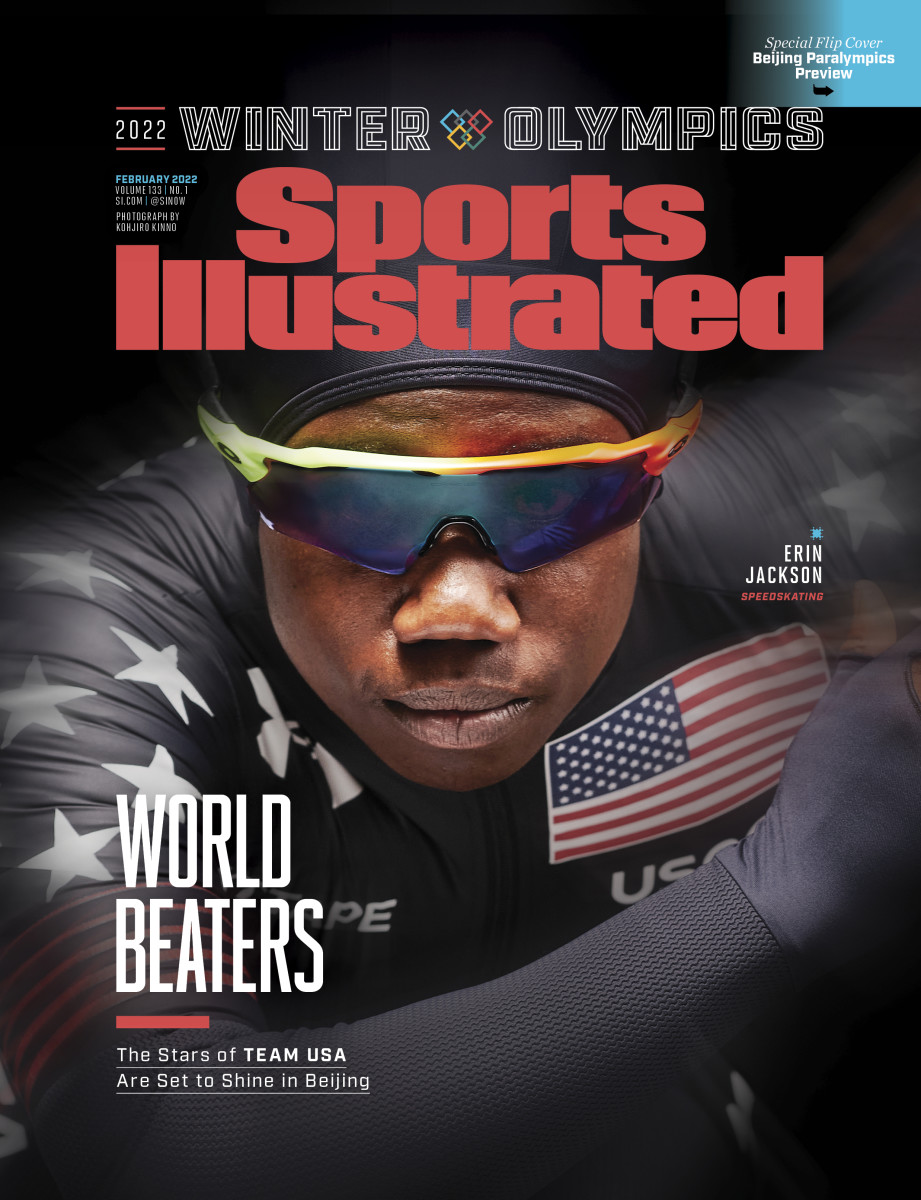

Erin Jackson Is Ready to Make a Statement on Ice

In the moments before she made the 2018 U.S. Olympic speedskating team, Erin Jackson wondered whether she could get herself onto the ice without falling down. She was in the process of converting from inline skating, and after just four months on ice skates, she still found some of the finer points of the sport challenging.

“I was a mess,” she says, laughing. “I needed someone to hold me up.”

Jackson shocked everyone—especially herself—with her performance during qualifying. She grabbed a spot on the team and then treated her trip to PyeongChang, where she finished 24th out of 31 in the 500 meters, as a learning opportunity. Now Jackson, 29, isn’t looking to further her education at the Games; she’s looking to win. In 2021 she took first at four of the year’s eight World Cup races in the 500—becoming the first Black woman to stand atop the podium—and earned medals two more times. She’s now the U.S.’s best medal hope in the sport.

Order the February 2022 Winter Olympics Preview issue here

Jackson almost missed Beijing, when a slip in the 500 meters at Olympic trials in early January left her just outside the qualifying slots. But Brittany Bowe, one of Jackson’s closest friends and a medal contender in the 1,000-meter and 1,500-meter events, gave up her spot in the 500. “In my heart there was never a question that I would do whatever it took, if it came down to me, to get Erin to skate the Olympics,” Bowe said. “No one is more deserving than her.”

Jackson’s first memories are of herself as a toddler, tooling around in little plastic roller skates. Growing up in Ocala, Fla., she quickly became a “rink rat,” she says, “someone who goes to the open sessions, just hanging out with their friends, skating around to the music.” At 8, she tried artistic skating—basically figure skating on wheels—until her coaches began complaining that she was going too fast. So, she switched to inline speedskating and started racking up national titles while also competing in roller derby. But an inconvenient truth nagged at her: Inline skating is not an Olympic sport.

So during a trip to the Netherlands in 2016, Jackson stepped hesitantly onto an ice rink, like fellow Ocalans and inliners turned Olympians Bowe and Joey Mantia before her. It was her first time on ice, and she did not like it. The motion wasn’t as close to inline as she had expected: Ice skaters generate power from their hips rather than their legs. And the surface itself posed a real challenge. She could not get on and off it without help, or even stop reliably. It was also cold. So Jackson returned to Florida and the temperate comforts of inline skating.

But Jackson’s inline skating had success caught the attention of the International Skating Union’s transition program, designed to identify athletes who might be good candidates for speedskating. She gave the ice another try a few months later in Salt Lake City, then quit again. Then, when the dreams of Olympic gold became unignorable, she returned for good in September 2017.

“There was never one of these things where she was already at the top in another sport and she was letting ego get in the way,” says her coach, Ryan Shimabukuro. “She said, I’m willing to start over again from square one.”

In January 2018, Shimabukuro scheduled Jackson to compete at Olympic trials, in Milwaukee, just to get her some reps against strong competition in anticipation of a serious effort in ’22. “I didn’t even tell my dad and my family that I was going to the Olympic trials, because to me, it wasn’t the Olympic trials,” she says. “I was going to do this race that just happened to be a place where other people were trying to qualify for the Olympics.”

Somehow, Jackson produced the best skate of her life to that point. Jackson began canceling her nonspeedskating plans: She couldn’t go to the Roller Derby World Cup in Manchester, England, in late January, because it would conflict with her travel to the Olympics. Not much else changed, though. Shimabukuro, trying to keep expectations reasonable, told her, essentially, Congratulations, but you’re still not that good. “She was very realistic,” he says. “She just wanted to take the opportunity to get better.”

Jackson does not remember her race in PyeongChang. “That’s still kind of a blur to me,” she says. It was the next season, when she was racking up top-10 finishes in World Cup races—despite being, she says, “I don’t wanna say terrible, but basically a terrible skater”—that gave her a sense of how good she could be. She was hanging in there with the best in the world while still learning. “It was like, How long is it gonna take me to get to the top?” she says. “Because that’s where I want to be, and that’s where I know I can be. So it’s just a matter of, How long is it going to take me?”

That drive comes naturally to Jackson. She graduated from Florida in 2015 with a degree in materials science and engineering, then picked up an associate’s degree in computer science and is earning another associate’s in kinesiology. She took a year off from classes to prepare for the Olympics with Shimabukuro in Salt Lake City, because when she’s in school, coursework is her top priority.

“She went to the University of Florida, and she never went to a football game. Like, what?” says Antoine Jackson, Erin’s cousin, laughing. “I would say she’s a pretty big nerd.”

Someday when she’s “done skating in circles,” Erin says with a chuckle, she hopes to combine her passions by developing new sports equipment or prosthetics. In the meantime, she wants her next Olympics to be very different from her first. Four years ago, Jackson caught the flu and missed the opening ceremony before her underwhelming finish. This year NBC will showcase her, and the media crush will be overwhelming. There will surely be talk of her following the U.S.’s Shani Davis, a two-time Olympic medalist, as a Black star in an almost entirely white sport. “It would be cool to see, this time next year, the makeup of [speedskating] look a little different,” Antoine says.

The bright lights might be distracting to some, but Erin believes they will energize her. She used to drive her inline teammates wild, she says, because she would falter during practice, then crush them in a race.

“I do better under pressure,” Jackson says. “I feel like the more pressure that people put on me, the more I’m going to be in the zone and ready to deliver. My issue is sometimes, if I don’t feel that pressure, I can get a little bit too relaxed. So yeah, I think the pressure is really important for making sure that I’m in the right mindset.”

Shimabukuro says, “She’s a game-day racer. The moment the competition starts, a switch flips.”

Still, he says he reminds Jackson that five years in, she is still “in her infancy in the sport.” She loves how much she has left to learn. But she sometimes feels impatient. She laments that her starts are inconsistent—they can range by as much as half a second, which, over 500 meters, is the difference between winning gold and missing the podium entirely—and she barely has time to practice them.

“To me it sounds irresponsible to not practice my starts outside of the race setting,” Jackson says. “But when you think about how many other things I’ve been trying to fix over the past four years, it’s like, We’ll get to the starts. We’ll get to those.”

Maybe in the next quadrennial. First, Erin Jackson is headed to Beijing, where she plans to win gold. Then she plans to get off the ice all by herself.

More Daily Covers

• Jessie Diggins Is on a Quest For More Than Medals

• Mikaela Shiffrin Is Focused on the Process

• Abby Roque Is Poised to Make History in Beijing, In More Ways Than One