Beijing’s Opening Ceremony Overlooked a Major Threat to Future Olympics

BEIJING — Martin Müller is a professor of geography at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, a centuries-old institution whose main campus is nestled along the northern shoreline of Lake Geneva. There he enjoys taking breaks from work to go for picturesque strolls, even if it means sometimes bumping into employees of the area's most famous resident, the International Olympic Committee.

“Interesting neighbor,” Müller says. “We know each other. We respect each other. Of course, we have quite some differences about the research that I’m doing on the impact of the Olympics.”

Last April, a few months before the pandemic-postponed Tokyo Games and less than a year before Beijing 2022, Müller and five fellow academics published a study that reached a sobering conclusion: Despite the IOC’s biannual bluster about the positive environmental impact of its signature events, the overall sustainability of the Summer and Winter Olympics have in fact declined over time. “The power of the Olympic spectacle is not currently harnessed to transform unsustainable modes of global economic production, but to entrench them,” Müller and his co-authors wrote. “This falls short of the humanist ideals of the Olympics to be a force for progress and improvement—for humanity and the planet.”

The 2022 Olympics, which officially began with Friday night’s politically charged snoozefest of an opening ceremony, is no exception. Overexploitation of groundwater has led to a severe shortage in greater Beijing, yet more than 1.2 million tons have been diverted for the first Games fully reliant on man-made snow. Organizers have lauded the National Alpine Ski Center in mountainous Yanqing for its reliance on wind and solar power, but its construction required the partial destruction of a nature reserve famous for its diverse flora and fauna. Chinese officials are also leaning heavily on carbon offsets in characterizing these Games as “one of the greenest” ever, even though by definition every new planted tree must be nullified by another negative environmental effect to make the math square.

“It’s not so much a China problem; we’re talking about an Olympic problem here,” says Jules Boykoff, a politics and government professor at Pacific (Ore.) University who has written four books about the Olympics. “Greenwashing is one of the richest traditions. That’s one of the Achilles’ heels of the Olympics: They talk a big green game, but in reality, the follow-through is limited at best.”

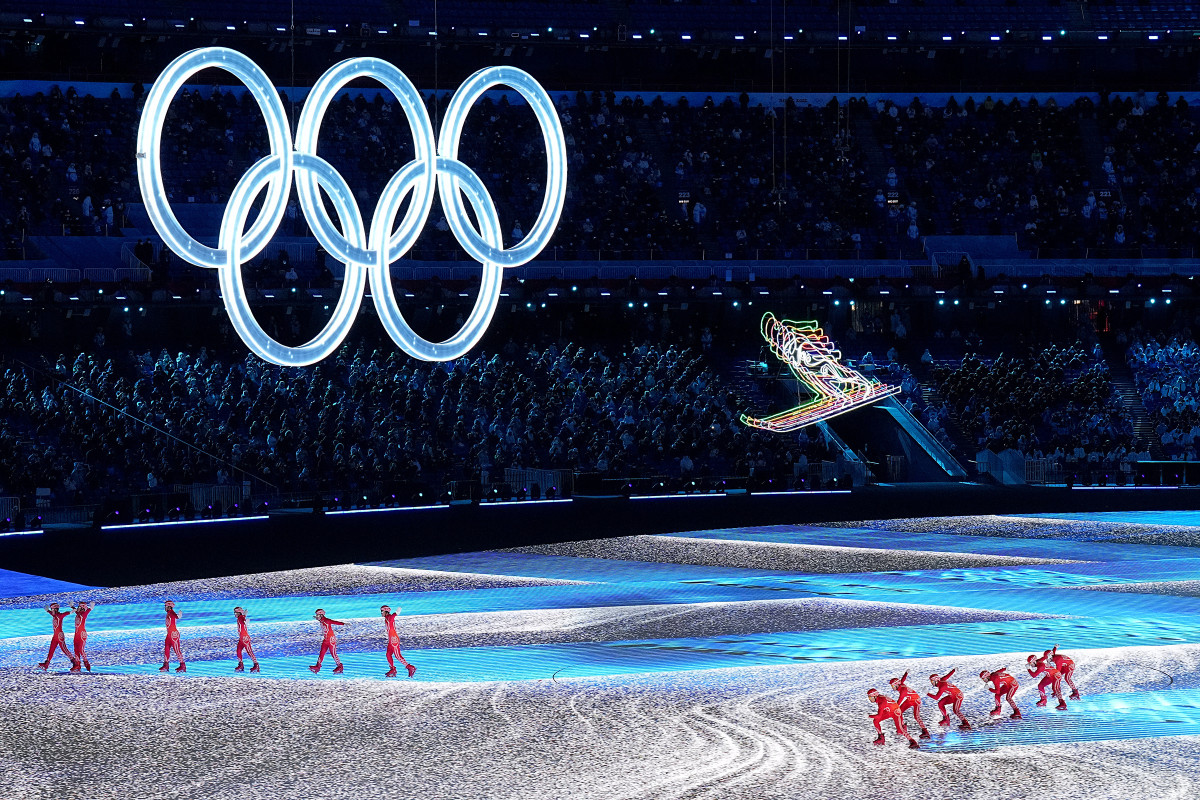

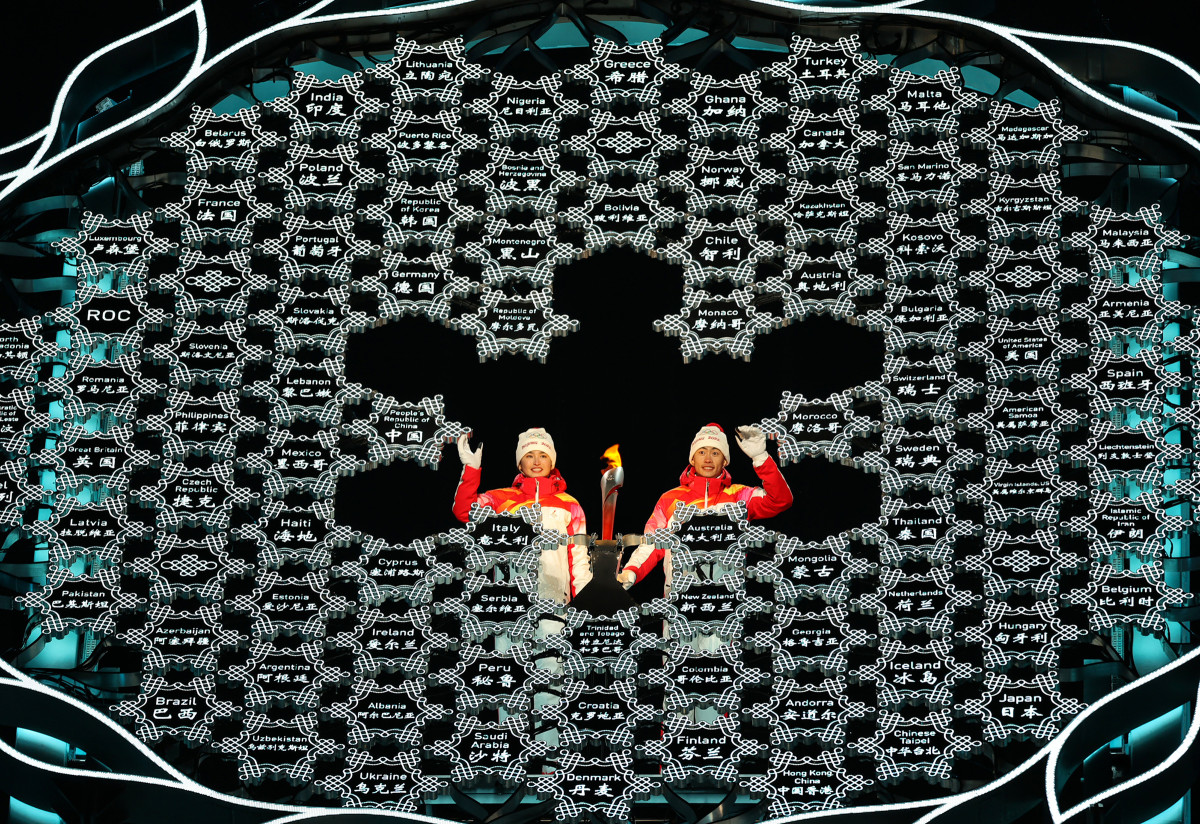

Predictably, the opening ceremony ignored these problems. Our planet still played a starring role, with imagery of snowflakes, ice cubes and blades of grass served up to distract viewers from the host’s rampant human rights crimes; at one point a giant image of Earth was projected onto an LED sheet that spanned the width of the Bird's Nest, Beijing’s National Stadium. But there wasn't so much as a nod to the grave implications of climate change that promise to threaten the future of the Games: According to a December 2021 study led by Daniel Scott, a professor and climate expert at the University of Waterloo, out of the 21 cities that have welcomed the Winter Olympics over the past century, less than half (10) are projected to have sufficient “climate sustainability” and natural snowfall to do so again in 2050.

“It's certainly on our minds as skiers, seeing less and less of real winter and more of manufactured winter,” U.S. cross-country skier Caitlin Peterson says. “We definitely need to act as a world.”

What motivated Müller to check the IOC’s sustainability claims wasn’t just concern about the future, though, but also “frustration with a lack of transparency” and accountability. “There’s no independently monitored and agreed-upon standard,” he says. “The Olympics are among the largest projects on Earth, but they poorly document it. Even getting information on costs is difficult.” Nonetheless he and his team forged ahead, digging through IOC reports, academic literature, official audits and other publicly available data from the previous 16 Olympics and applying them to nine indicators of sustainability, a daunting task that took four years and required translation from multiple languages.

Several key factors are driving the Olympics’ steady decline in sustainability, Müller says. “A big one” is their swelling size, less in the number of athletes than in the support staff, media, security personnel and so forth, many of whom must take fuel-guzzling planes to get there and stay in power-gobbling hotels for the next three weeks. Another is the demand for high-quality sporting venues, the construction process for which “rated negatively on the ecological impact” on Müller’s scale.

“And the third is the IOC is increasingly demanding more legal exceptions from the hosts to guarantee its commercial interests,” Müller says. “In our model, there’s ecological and economic and social dimensions. On the social dimension, this is a negative impact on the rule of law. It creates legal uncertainty, and many people suffer for that.”

Since publishing last year, Müller has twice been invited to make the brief walk to IOC headquarters and present his findings. “They recognized we had a valid model, and that they have to work on some issues,” Müller says. But officials also pushed back, notably in claiming that the Olympics were trending toward full carbon neutrality. “Vancouver 2010 reported 120,000 metric tons of direct carbon emissions; Beijing is anticipating 1 million metric tons,” he says. “For me, that undermines the claim.”

The IOC also tried to push Müller to “use more indicators in studies they’d conducted internally,” to which he noted the obvious conflict of interest and declined. And while he recognizes certain best practices at the 2022 Olympics—such as its use of renewable energies powering a large set of venues—even those are best viewed through a cynical lens.

“For me, this nevertheless is window dressing in view of ramping up coal in energy production in China,” Müller says. “It’s presenting a nice image, as the camera turns on Beijing.” Then there is the lack of accountability for both the IOC and the host.

“Typically you have the organizers and the government’s claims, who want you to believe that they're the model of sustainability,” Müller says. “And typically there is independent media, NGOs, academics who dig into those claims and challenge them. That second side is missing in China, because there is no independent media, academics are scared to publish anything on this, so the only information available is from the organizers. It’s a little like if I allowed my students to mark their own exams.”

Müller hasn't heard back from the IOC after his second meeting, last fall, but he hasn’t given up hope. “They’re moving,” he says. "I’m not saying nothing is changing. Concretely they’re saying they want to spread more events geographically to make use of existing facilities.” In the meantime, as a former alpine and downhill skier who picked up cross-country skiing during the pandemic, he is certain that he will tune in when the action gets underway—before it's too late.

More Olympics Coverage:

• Inside Beijing's Closed Loop at the Winter Olympics

• The Mysterious Case of the Missing Luge Equipment

• SI Picks Every Medal at the 2022 Olympics