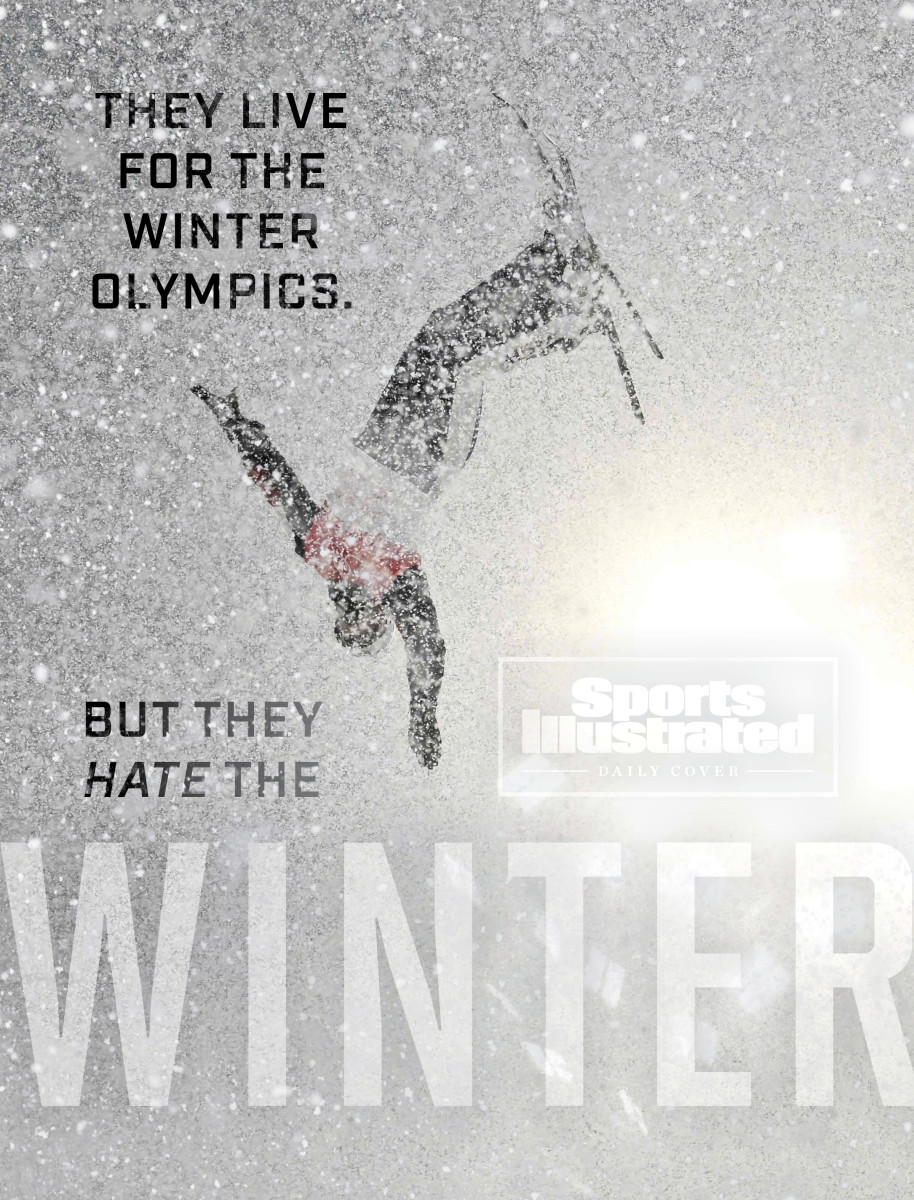

‘It’s a Necessary Evil of Doing a Snow Sport’

BEIJING — Sometimes, when Summer Britcher is waiting at the top of the luge track, hands ready to grip the handles and explode at speeds north of 70 miles per hour, body tensed, mind focused on steering the ideal course, she pauses and allows herself to feel excited—and not just about the race.

“I’m like, man, in 45 more seconds I’m gonna be warm,” she says. “As soon as I pull off, I can’t feel the cold, right? When you’re going, you don’t feel the cold. … You’re so in the zone and in the moment, on this super-hard ice—which is my favorite condition to slide on—and then the run ends, and I’m yelling cuss words about how cold it is and running to get my jacket.”

As temperatures here dip below zero degrees Fahrenheit, snow flurries erase visibility and blustery winds postpone events, some winter Olympians have a confession to make: They hate the winter.

“This is the story I’ve been waiting for,” says Britcher.

Indeed, aerial skier Ashley Caldwell thinks there are more of them than will admit it. “Nobody likes being cold,” she says. “They like being warm in the cold.”

She is not among them, though. She likes being warm in the warmth. So how did she end up flipping and twisting through 10-degree air for a living?

“Well, see, they tricked me,” she says. “We learn all of our tricks in the summertime! We jump into a pool! Summertime is warm and you jump into a pool—it’s not so scary. My first couple of jumps on snow I was like, I don't know if I can do this. You get snow up your back and it's so cold.” But by then, it was too late. “I love the sport so much that you kind of just deal with the cold,” she says. “It’s a necessary evil of doing a snow sport.”

Indoor winter athletes have it easier, although they can’t exactly work from home when the weather is terrible. And the commute can be brutal. Mexican figure skater Donovan Carrillo brought his biggest coat to Beijing but was still taken aback by the temperature. Australian figure skater Brendan Kerry moved full time in 2019 from subtropical Sydney to Moscow to work with elite coaching. The rink is the same temperature it was in Australia. As for the rest … well, he is still adapting.

“The cold is manageable,” he says. “I hate that there’s no sun, or the sun’s only out for a little bit. That’s what’s really upsetting, ’cause you wake up and you’re like, ‘Why is it so dark? This is unacceptable.’ Back home, my family’s like, ‘Oh, it’s 40 [degrees Celsius, or 104 Fahrenheit]; we’re boiling.’ I’m like”—he gives a thumbs-up, then adds, “But it’s not this finger I’m holding up.”

To combat the melancholy, Kerry goes tanning whenever he gets a chance. “I don’t care about my complexion,” he says. “I just want that eight minutes of sunlight.”

Mental health is key. So is physical health, and on that front, most important is dressing properly. For the Opening Ceremony—which was cold enough that at least one person there developed a mild case of frostbite—Britcher stuffed two pairs of toe warmers in each boot, one above her foot and one below, and a pair of hand warmers into her hat. Caldwell and her boyfriend, fellow aerialist Justin Schoenfeld, often wear heated insoles. Caldwell also tries to nail the timing. The key, she says, is “making sure you don’t get sweaty before you get outside. I don’t put on my layers until I’m right about to go outside or else you get sweaty and wet, and then you definitely freeze.”

But eventually they have to shed all those layers, and they agree those are the worst moments: waiting for their heart rate to climb, looking longingly at the jacket they have just discarded. Most of them flail their limbs wildly and hope the cameras are looking elsewhere. They would cry, but their eyelashes would freeze.

“We always make that joke: We chose the wrong sport,” says U.S. aerial skier Eric Loughran. “We’ve gone to some really cold places in the past, where it's been minus-20, minus-30 Fahrenheit, and we're just like, ‘This is brutal,’ especially in the suits we wear sometimes.” Normally, when he enters the gate atop the course, adrenaline warms him up. But last January, in Yaroslavl, Russia, temperatures dipped into that range as he weathered a 10-minute course hold. Finally he yelled down to a coach, who threw him a coat. He grimaces remembering the moment.

“That was the coldest event I’ve ever jumped in,” he says. “I was in the team event with Ashley and Justin, and I remember us up top trying to get our toes warm. We were like, ‘This is miserable, man.’ But we knew the only way we're gonna get [inside] is if we hit the jump one more time.”

And even that is made harder by bitter, biting cold. As anyone who has waited for a dog to pee in the middle of February knows, the temperature quickly becomes the only thing on your mind.

“You’re trying to be high-performance and you can’t,” says Caldwell. “That’s also frustrating. You’re like, oh my gosh, I have to do this really difficult task and I’m freezing. That’s annoying. It also makes it scarier. Because if you’re cold, you just want to bundle up and go inside and go into a hole. And that’s not a good mental space to do a hard trick.”

For lugers, though, the worse the weather, the better. Sleet and ice make the track fast. So Britcher was thrilled to be miserable last week. She survived the cold in Beijing, finishing 23rd after colliding with a wall in her first run. She called the experience “joyous.” And she knew exactly how she would celebrate: with a trip to Miami.

More Olympics Daily Covers

• Inside the Power Dynamic—and Secret Code!—That Makes the U.S. a Curling Threat

• SI Picks Every Medal at the 2022 Olympics

• Mikaela Shiffrin Is Focused on the Process