No Russia, No Problem

If you needed a reminder that, for centuries, Europe has been riven by conflict and territory grabs and shifting alliances, you could do worse than spending time in Montpellier, France. Sitting pretty on the Mediterranean, halfway between Barcelona and Nice, this city of beach breezes and olive trees was ravaged by pirates in the Middle Ages, became a stronghold of the Crown of Aragon and was sold off to France, where it stood as a tactical 17th-century fortress under Louis XIII.

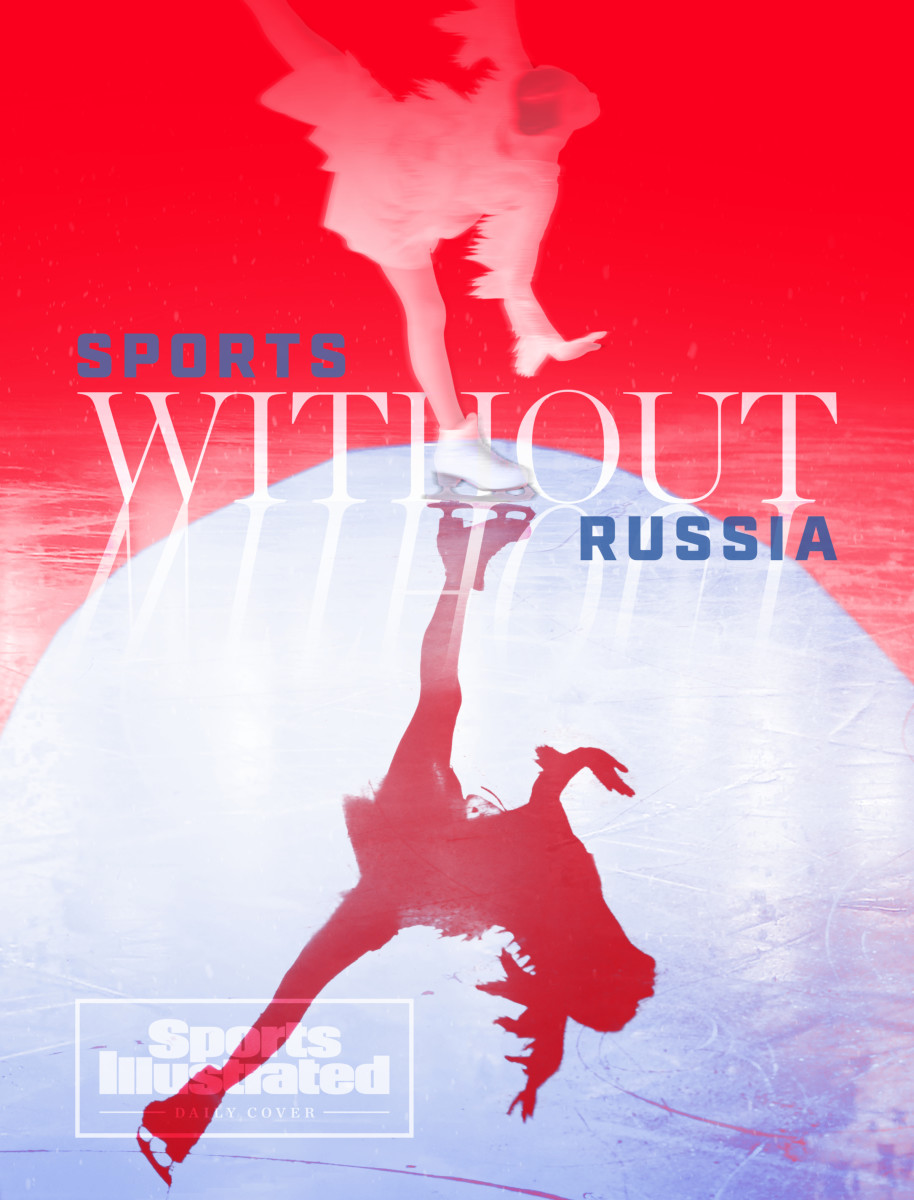

This week Montpellier, France’s seventh-largest city, again felt the reverberations of a divided continent. Only this time, it has been as host city of the World Figure Skating Championships. Quite apart from featuring the sport’s finest athletes, the event offered a glimpse of the sportscape with Russia lopped off. As the pre-printed promotional material made clear, Russians were expected to dominate the championships. Instead, they were frozen out.

It was barely a month ago at the Beijing Winter Olympics that Russia played an outsized role in the skating events. Competing, technically, as “neutrals,” and not for their country—a legacy of the doping sanctions against Russia that run through 2022—the “ROC” (Russian Olympic Committee) skaters confected scandal while minting melodrama and medals in equal measure.

In Beijing, Anna Shcherbakova won gold in women’s singles and then, memorably, celebrated alone, looking disconsolate. Alexandra Trusova, the silver medalist, was tearfully irate that she did not win, in spite of attempting five quadruple jumps. Kamila Valieva, the 15-year-old, the precocious pre-Games favorite, wilted under the pressure of both the moment and a positive doping sample to finish fourth. Valieva was integral to Russia’s winning the team competition, but did not receive a medal pending the resolution of her doping case.

Within days of the Beijing Games’ closing ceremony—and the thinking goes: the timing was no coincidence—Russia launched its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. Though President Vladimir Putin was a warmly received guest in Beijing, the IOC acted with uncharacteristic swiftness and moral conviction and encouraged all governing bodies to prohibit Russian athletes from competing.

The International Skating Union was quick to heed this request. Citing “solidarity with all those affected by the conflict in Ukraine” and “in order to protect the integrity of ice skating competitions” it banned skaters from Russia, as well as from Belarus, which supports the war, from participating in international ice skating events.

That same week, FIFA announced a ban on all Russian soccer teams, which will undo the men’s national team’s bid to qualify for the World Cup. UEFA moved May’s Champions League final out of St. Petersburg to Paris. Track and field and rowing are among dozens of other federations that followed suit. (An appeal lodged by Russia with the Court of Arbitration for Sport was denied.) Sebastien Coe, president of World Athletics, the governing body for track and field, asserted that Russia’s act of war was a “game changer.”

The speed and unanimity with which all of these sports bodies acted was remarkable. At last, here was a clear moral stand on behalf of the athletic universe. But zoom out, and the picture grows fuzzy. The IOC took its stand just after hosting the Olympic Games in Beijing—where the ruling authoritarian government stands accused of assorted crimes against humanity, most critically ongoing genocide—and while the Paralympic Games there were still being played (now without Russian athletes). FIFA is scheduled to host its next World Cup in Qatar, speeding ahead through a flurry of human rights abuses associated with the event.

The circumstances around the Russian invasion of Ukraine are, of course, unique and extraordinary. But there is also the cold calculation that’s almost certainly been made in recent weeks in every office of every international sports body: The sports world can get along just fine without Russia.

In Montpellier, Russia’s absence was not of the glaring variety. If the roster of skaters was altogether different from the slate in Beijing—often the case for this event in the years with Olympics; fresh of his singles gold, American Nathan Chen, for instance, begged off citing a “nagging injury”—the crowds filing into Sud de France Arena did not much seem to mind. Notwithstanding a clot of fans brandishing blue-and-gold nail polish and temporary tattoos, there was little indication that a war was raging 2,800 miles to the northeast.

The skaters took pains to stress not only that the event bore no asterisk, but that they devoted little time or bandwidth to the Russians. “I think more about the Ukrainian skaters who cannot train [than about the Russians],” France’s Guillaume Cizeron, who won the ice dance gold in Beijing with partner Gabriella Papadakis, said in a press conference. “It is around them that the discussion should take place … but they have other priorities than training.”

One official, who preferred to remain anonymous, remarked that, if anything, the event would be more legitimate, not less, since without Russians competing, there would be considerably less skepticism and speculation “over who was and was not doping.” Another insider noted that if Russia’s absence will be felt anywhere, it’s off the ice, including conference rooms where decisions about eligibility and minimum ages will now be made without Russia at the table.

Sports is not, of course, the only sector exercising its soft power. Down the coast from Montpellier, the Cannes Film Festival announced that it will not welcome “Russian delegations” this year. Eurovision, the annual continent-wide song contest, has also banned Russia this year. (The Ukrainian entry, meanwhile, has already emerged as a sentimental favorite for May’s final.) “Shocked and horrified,” the International Cat Foundation announced it was banning Russian-bred felines. Throughout Europe, venues have canceled dates by Russian ballet troupes, just as the Metropolitan Opera in New York cut ties with a Putin-extolling soprano.

Still, in this case, isolation (and cancellation) through sports is thought to have a special level of valence. As Putin has amassed and consolidated power, sports have been a cornerstone of his mythology. Among world leaders, he takes first place in using strength and power and victory of his country’s athletes as a broader representation of national supremacy. Putin sits cageside at MMA fights and gladhands in suites at soccer matches. He stages photo ops swimming the butterfly stroke. He laces them up and scores bushels of goals against former NHL players, all surely trying their best. His secret palace was recently revealed to include a full-sized ice-hockey rink—along with an “aquadisco,” full casino and strip club. Like a look-at-me teenager on Instagram, Putin has a vast library of selfies posed alongside Russian athletes.

One of the undeniably high points of Putin’s 18 years in power came when Russia spent $50 billion to stage the 2014 Sochi Games—more than four times the price tag for the ’20 Tokyo Summer Games. Overlooking a systematic doping scandal, Russia won more medals than any other country. And, again, overlooking a systematic doping scandal, the Games brought a great infusion of national pride. Precisely four days after the closing ceremony, Putin annexed the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine.

Four years later, Russia hosted the 2018 World Cup. Again, Putin used sports as pretext. “People have seen that Russia is a hospitable country,” Putin said at the time, “a friendly one for those who come here.” (To which FIFA president Gianni Infantino responded, regrettably: “The world has created bonds of friendship with Russia that will last forever.”)

Banning—and, in effect, humiliating—Russia as a sports power is a direct shot at Putin. Old advertising slogan: “Hit ’em where it hurts. Right in the image.”

Then again, is sports overstating its importance? Does any of this really matter? “It’s too late,” says Morgan Menahem, a top French sports agent. “We’re talking about a country—a person, really—who is invading another country, who wants to be a superpower. We think they’re going to reconsider because their ice skaters can’t be in a championship?”

The sports ban might be rooted in moral conviction. Countries that expect to be included in the international community cannot invade sovereign countries. On the threshold of a third world war, you depress every possible lever to stop the offender.

But more cynically, sports can afford to isolate Russia, a bit player in the global sports economy. With its Olympics and World Cup hosting duties in the rearview mirror, Russia is not scheduled to stage any events that cannot be relocated. A country with a GNP roughly that of Ohio—and that was before the ruble was reduced to rubble, devalued to historic lows—Russia does not significantly move the sponsorship and television needles.

Asked about the impact of the Russian invasion on the global sports economy, Scott Rosner, academic director of the master of science in sports management program at Columbia University, focused on the indirect impacts. He notes “changes in fan behavior that could flow from an increase in gas prices. NASCAR would be one sport that could face some attendance issues.”

Says Menahem, the French agent, “Russia is a big country. Russia is a country that is often a convenient sports rival. But drill down and what’s there? You can say Gazprom sponsorship, but that’s mostly within Russia. The real contribution [to global sports]? It’s two main things. Oligarchs who buy teams and a sports system that develops athletes who usually leave the country, first chance they get.”

Their assets frozen, those Russian oligarchs are, in some cases, being forced to sell their sports holdings. While fire sales might impact franchise valuations in the short term, there will always be eager buyers. Will Roman Abramovich’s forced sale of Chelsea, ultimately, be any more or less convulsive than, say, Mikhail Prokhorov’s sale of the Brooklyn Nets in 2019?

The more interesting issue: Barring an unexpectedly abrupt end to the war, are leagues and tours prepared to drive sports sanctions further and to freeze out individual Russian athletes? Will the NHL, for instance, suspend Alex Ovechkin—whose Instagram avatar still features him posed giddily alongside Putin—and the 40 other Russian players in the league? (One of whom, the Rangers’ Artemi Panarin, has repeatedly and at great risk spoken out against Putin.) Will soccer leagues throughout Europe send home the Russians playing abroad?

The argument in favor: The attempt to eliminate a sovereign nation calls for a strong response. The international community needs to use all the levers it can. Sanctions, almost by definition, bring collateral damage. Sorry, if fairness is the guiding principle, why don’t we start with the Ukrainians, whose country is being destroyed? The argument against: The sins of an autocratic leader, no matter how egregious, should not be visited upon individual athletes.

University of Pennsylvania Law School professor Mitchell Berman, who often works at the intersection of sports law and moral philosophy, goes so far as to suggest that not only should no individual athletes bear the consequences of state action, but participating in sports may be a human right. Steve Simon, CEO of the WTA Tour—which has a strong record lately on geopolitical moral stands—put it similarly in an email to Sports Illustrated: “The WTA feels strongly that individual athletes should not be penalized due to the decisions made by the leadership of their country.”

Still, in Simon’s sport, tennis, where both Russians and Ukrainians figure prominently, this debate rages. The sport followed FIFA and the Skating Federation and banned the Russian team from the Davis Cup and the women’s equivalent, the Billie Jean Cup. But individual Russian players have not faced a ban. So it was that when Russia’s Daniil Medvedev became the world’s No.1 player the week of the invasion, he faced more questions about his country’s incursion than his triumph. While he answered mostly in platitude—“Ask 10 people their opinion, you get 10 answers”—his wife Daria, pointedly, wore colors of Ukraine’s flag as she watched his matches.

Marta Kostyuk, an ascending Ukrainian player, talked about the awkwardness of running into Russian counterparts in locker rooms and lounges: “Nobody has told me that they regret what their country is doing to mine. Nor have they apologized to me or other Ukrainian players. To me, that’s shocking. I have no explanation for why the Russians behave like this. It disgusts me to go on the court and see that their only problem is about making money.”

She added that the Russian athletes’ fallback response that they “want peace” rang vague and hollow, pointing out that “peace” could be interpreted as requesting Ukraine surrender. “You don't need to be involved in politics to know what's going on, who’s invaded who, who’s bombing who. It’s very simple. You can’t be neutral in this situation.”

At Wimbledon, which begins in June, organizers have spoken about banning Russian players until and unless they “get some assurances” that the players do not support Putin.

Again, this stance may be principled. But there’s little economic risk. For as many Russian players that fill the Wimbledon draws, there are no Russian sponsors and negligible Russian television rights revenue. If the London-based oligarch who came to watch is now persona non grata, well, rest assured someone else will happily pay to fill that seat.

In the vocabulary of the day, it’s an asymmetrical war, Russia versus the global sports community. Russia needs sports (desperately) more than sports need Russia.

One country over from Russia, of course, China’s authoritarian government stifles democracy, smothers a free press, carries out innumerable human rights abuses and conducts a genocide of the Muslim Uighur minority. But this bad actor has real market power. The IOC, so vocal in condemning Russia, has bent over backwards to explain away China’s behavior. The NBA, which has cut off all business and broadcasts in Russia, has famously contorted itself to keep its games streaming into China. Just as Apple and Starbucks and McDonalds and Coca-Cola—so quick to close up shop in Russia—continue on, business as usual, in this far more critical market.

If and when China invades Taiwan, we’ll see whether the global sports community continues its deployment of soft power. That’s where and when the polyurethane really meets the road.

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Their Countries Are on Opposite Sides of a War, but They Stand United

• Inside Tito Ortiz’s Tumultuous Term Governing His Hometown

• ‘I Am Lia’: The Trans Swimmer Dividing America Tells Her Story