Muhammad Ali’s Iconic Olympic Torch Lighting Moment Almost Never Happened

The following is excerpted from From Saturday Night to Sunday Night: My Forty Years of Laughter, Tears, and Touchdowns in TV. Copyright © 2022 by Dick Ebersol. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

In December 1995, I went to Atlanta for another meeting with Billy Payne, the head of the Organizing Committee for the 1996 Summer Games, to go over a variety of topics, chief among them the Opening Ceremony. The talented Don Mischer, who’s directed many Opening Ceremonies and Super Bowl halftime shows, was there, along with Ginger Watkins, who was the executive in charge of the ceremonies under Payne, and a few other people. A little more than halfway through the meeting, I brought up something that had been on my mind.

“One of the things we haven’t really tackled yet,” I said to Billy and the group, “is how you’re going to deal with lighting the Olympic cauldron in the show.”

As an Olympic nut, I knew going back decades that lighting the cauldron was the dramatic climax to the Opening Ceremony. As the last big moment in the show, it would always be its most lasting moment, something for the audience to remember as the competition kicked off. Most typically, the job tended to go to an Olympic star from the host nation. In 1984, Rafer Johnson, the decathlete who’d been the star of my 1972 Ancient Games film, had lit it in Los Angeles. In Seoul in 1988, a South Korean schoolteacher and dancer had joined a young Olympic marathoner. And in Barcelona, organizers had done a great job of amplifying the drama with archer Antonio Rebollo Linan’s role in shooting the arrow. I felt like that had upped the ante in terms of the statement that an organizing committee could make, and now in Atlanta, Payne and his team had to make the most of that opportunity.

“I actually have thought about it,” Billy said. “And I’m thinking it’ll be Evander Holyfield.”

Holyfield made some sense as a choice. He was an Atlanta native, had won a medal at the ’84 Games, and then had become the heavyweight champion of the world for two years.

But to me, there was a far better choice, someone who’d been in my head as the perfect figure for months.

“I really think you should ask Ali,” I said.

My memories of Muhammad Ali went back, like most people of my generation, to when he’d burst onto the scene in the early sixties, after winning a gold medal at the Rome Olympics. As a young sports fan, I’d watched him rise as Cassius Clay, shocking Sonny Liston to win the world title. Then, after he’d refused to enter the army on religious grounds as a Muslim, Ali’s boxing license had been stripped. His title belt and his livelihood were taken away, and he was sent into sports exile for three years. When he came back, after his case had gone all the way to the Supreme Court—even a conservative bench had unanimously ruled 9–0 in his favor—he was almost thirty, his prime taken away from him.

But the second act that followed—his epic victories over Joe Frazier and George Foreman—had transformed him from one of the great boxers and most colorful characters of all time into the most famous athletic figure on earth, beloved by millions. Along the way, I’d met him a few times through his connection with Howard Cosell, and even went down to Miami a couple of times with Howard to cover his training camps at the 5th Street Gym for Wide World of Sports reports. In the decades since, all those years in the ring had taken their brutal toll, and Ali had revealed that he had Parkinson’s disease. It had quieted what often seemed like the loudest voice in the world, but at the same time, that softening had made him a different kind of icon. A legend known throughout every corner of the globe, a man of faith and peace, and, to so many now, a true American hero as well.

But even when I laid all that out to him, Billy Payne wasn’t so sure of the choice.

“I’m going to have a hard time selling a draft dodger here,” he sadly lamented to me.

“A draft dodger? He’s not a draft dodger!” I tried to tell him. He was missing the point—the potential wonder of the moment that Ali could create. But if that was his argument, I was ready to counter.

“Respectfully, let me just make sure that you know the history correctly,” I said. “He was willing to go through the legal process. He was willing to forgo the massive amount of money he could earn in the ring for all this. He was found guilty, and he was on his way to prison, but the federal court of appeals in the state of New York threw it out. And the Supreme Court also agreed fully with that decision three years later, and he was cleared of all charges. He did it all despite sacrificing almost four big-money-earning years. And he didn’t run away from the country. He didn’t go to Canada. He was willing to stand on his principles.”

I made my case a bit longer, and got Billy to promise to at least consider it. Then, after the holidays, I went to work further on it, on two fronts. First, I had our top feature producer, Lisa Lax, start working on a long film on Ali to present to Payne. The film would tell the whole story—from his days as an Olympian to the stand he took on Vietnam to his ascendance to legend. I also called a wonderful man named Howard Bingham, a friend and photographer who had been one of Ali’s closest friends for years. I needed to find out if Ali could even physically do what I’d dreamed up, and if he could do it, would he do it?

As Lisa got to work, Howard got back to me quickly with a message from Lonnie Ali, Muhammad’s wife. If we came up with the right way to do it, Ali was in.

The second week of May, I knew that Billy was having surgery, and would be recuperating at his lake house north of Atlanta. I called him and told him I was going to send him Lisa’s film to watch while he was resting. A few days later he called.

“Okay, I see what you’re saying. That was a fantastic film. I’m seeing what you’re seeing. He’d be a popular choice.”

Chalk another one up for storytelling.

“But I still have my misgivings, Dick. Do you even know if Ali would be willing to do it?”

“Do you really think,” I said with a smile, “that I would have gone through all of this if I didn’t know the answer to that question?”

I arrived in Atlanta on the last day of June, almost three weeks before the Opening Ceremony. While we had plenty of other sports business going on in the States and overseas—Wimbledon, and the upcoming baseball All-Star Game among them—the Olympics were by far the biggest few weeks of the year, and with our commitment to the IOC solidified for the next twelve years, we were all going to do everything we could to make sure everything went as perfectly as possible.

It was like the beginning of summer camp, as members of our staff and favorite freelancers trickled into Atlanta, checked into their hotels, and got to work at the International Broadcast Center and the venues. There were a lot of hugs, and a real sense of excitement with the start of the Games just days away. And, of course, the biggest thing on my mind was the Opening Ceremony.

I’d had to call Andrew Young, the former mayor of Atlanta and the only African American member of the executive committee of the Games, to convince some holdouts in the group even after Payne had agreed, but Ali was all set to light the cauldron, and we just needed the secret to stay that way. As for logistics, Don Mischer had ingeniously designed the staging for the climactic moment, with a five-story ramp connecting to the track in the brand-new Olympic Stadium (the future Turner Field; construction had just been finished days earlier) for the athletes to walk up and down leading to the Parade of Nations. Initially, the placement of the cauldron—high atop a tower beyond the ramp—seemed like it would be a problem for Ali if he was going to light it. But then someone on Mischer’s team had brainstormed a solution: he could light a fuse on a rocket, and the lit fuse would travel up on a wire to the cauldron.

Still, there was a lot of uncertainty as Friday night, July 19, approached. There’d only been one rehearsal with Ali a few evenings earlier, and it had been completed in darkness, after midnight, with only a few people on Mischer’s team present, and without the lighting fuel—because the stadium was immediately adjacent to a national interstate highway, nobody wanted to take any risk that people would see a flame being lit and start wondering what was going on as they drove by. The magic of the moment was dependent on the element of total surprise. No one could be expecting to see Ali at the end of the ceremony.

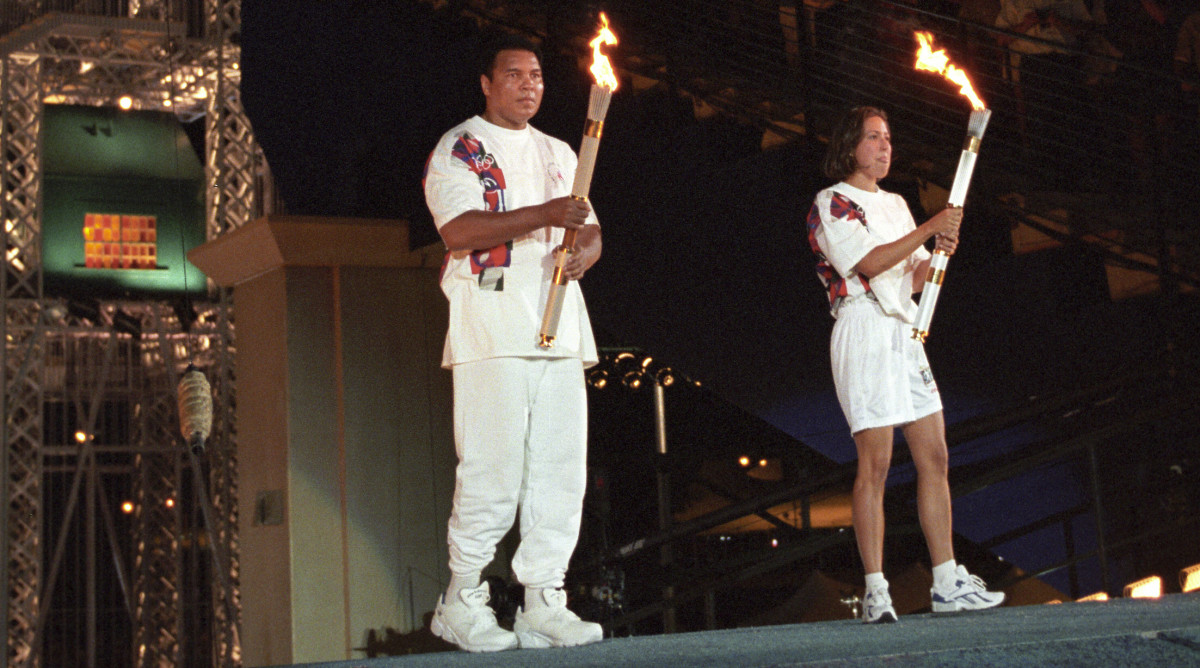

It was a hot, clear night, and the show, as always, was a few hours long, with an artistic component followed by nearly two hundred delegations of athletes marching into the stadium up and down the ramp in the Parade of Nations. Then the moment built from there. Evander Holyfield did end up getting a big part—he jogged the Olympic Torch into the stadium, and then handed it off to Janet Evans, the Olympic swimmer. Janet took half a lap around the track, and then headed up the ramp, where a figure emerged out of the shadows. The Greatest.

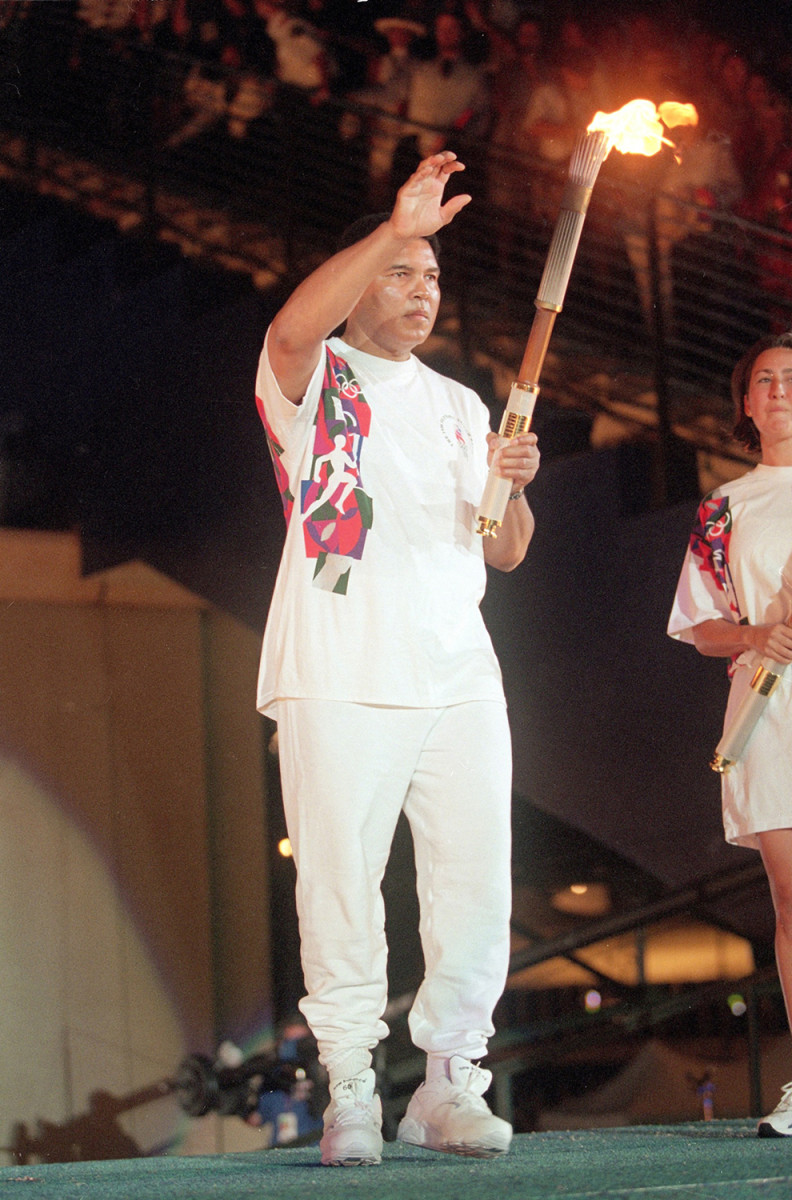

Eighty-five thousand people gasped at once. President Clinton, who was in the stadium that night, told me a few days later on a visit to the IBC that the reaction to the sight of Ali—and the recognition—resulted in “the loudest hush” he’d ever heard in his life. Ali, dressed in all white, holding the torch with his right hand, his left hand shaking wildly from his Parkinson’s. Once the most gifted fighter in the world, still, despite everything else, exuding a remarkable presence. There was a stunning dignity to it that made it all the more poignant, more striking than any of us could have imagined.

On our broadcast, I’d made sure for weeks that Bob Costas and Dick Enberg hadn’t had a clue about what was coming—I wanted their reactions of shock and surprise to be pure and genuine, completely in the moment.

Bob, as ever, immediately sensed the significance of what was happening.

“Look who gets it next!” he exclaimed as Janet passed the torch to Ali.

“The Greatest!” Enberg added. “Oh my!”

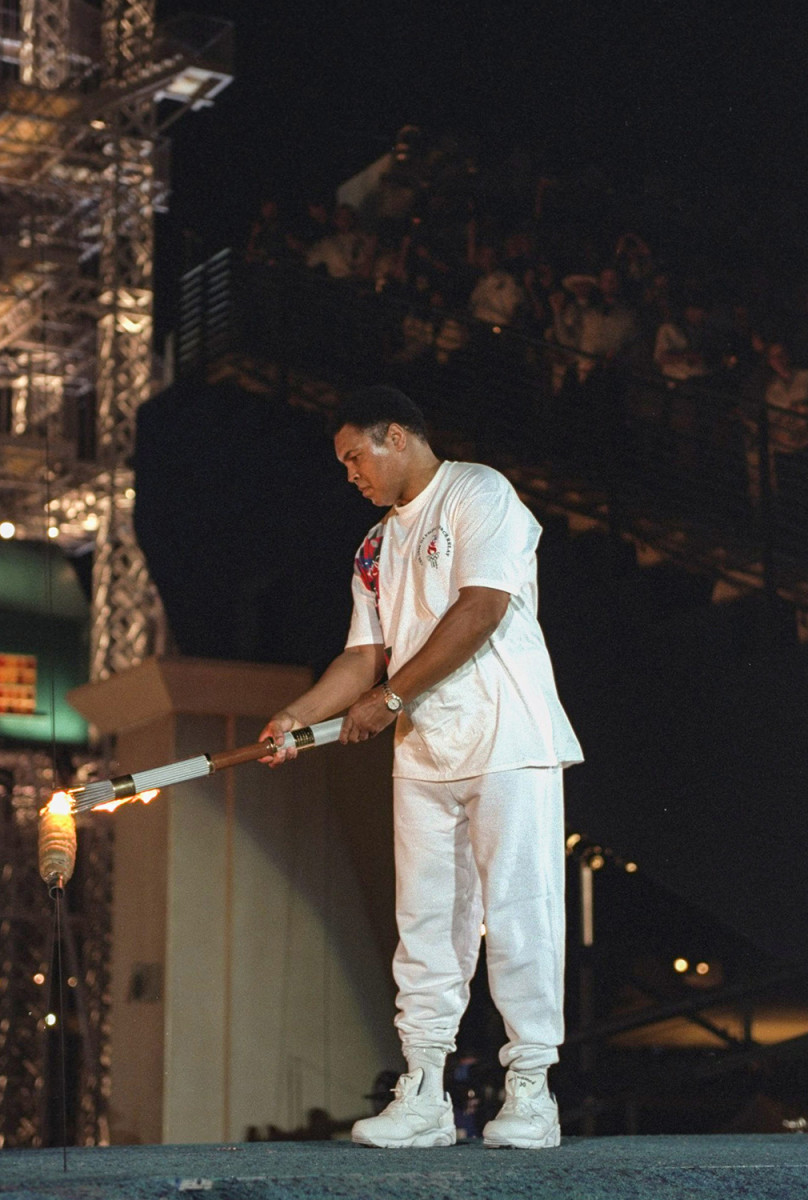

With hundreds of millions watching around the world, Ali took the flame from Evans, held the torch aloft for a moment, and then turned and held it downward to light the rocket.

And it wouldn’t light.

In our production truck, it felt like the perfect moment was breaking apart. Without a true rehearsal, no one knew how hard the fuel would be to light. There was an ample amount of fuel to be lit, but the mechanism to get the cauldron to light moved slower than anyone expected. And so Muhammad stood there holding the torch, with the flames flaring back at him, seeming like they were about to burn his arms, for what felt like an eternity. But he stood there patiently, even bravely, and waited those few extra beats—which felt like hours to the rest of us—until it finally lit.

The hush turned to a roar, with parts of the crowd breaking out in a chant of “Ali, Ali, Ali.” It was nothing short of glorious, simply a magnificent way to start the Centennial Olympic Games.

Ali would stay in Atlanta for the Olympics and attend a whole series of events throughout the Games. The day after the ceremony, I called the International Olympic Committee’s leader, Juan Antonio Samaranch, in his room in Atlanta; he was also thrilled with how it had gone. But I had another idea to talk to him about. The story that had long been told was that Muhammad had thrown his gold medal in the Ohio River when he’d gotten home from Rome, after getting turned away at a Louisville restaurant because he was Black. The truth, however, as Muhammad had told me himself in a conversation before the Games, was that he’d simply lost the medal. Now, talking to Samaranch, I asked him what he thought of giving Ali a recast medal (the IOC keeps all the castings of medals from every Games). Sure enough, at halftime of the gold medal game in men’s basketball between Team USA and Yugoslavia, the IOC presented Ali with a new medal. It was another moment to savor.

Maybe the best part, though, came a couple weeks after the Olympics, when I got a call from Lonnie, Muhammad’s wife. They’d just gotten back to their home in Louisville from a day at the PGA Championship at nearby Valhalla Golf Club.

“For so long,” she told me, “Muhammad hasn’t wanted to go out in public anymore. He’s just so embarrassed by his condition. But after Atlanta, he agreed to go to this tournament.

“And when all these admirers surrounded him”—I almost felt her beaming over the phone—“it was like he was himself again!”

And with that, Muhammad Ali returned to public life, and began again to thrill people all over the world by simply showing up places. He didn’t speak much, but somehow, even in silence, he emitted an otherworldly presence wherever he went. And it all began in Atlanta.