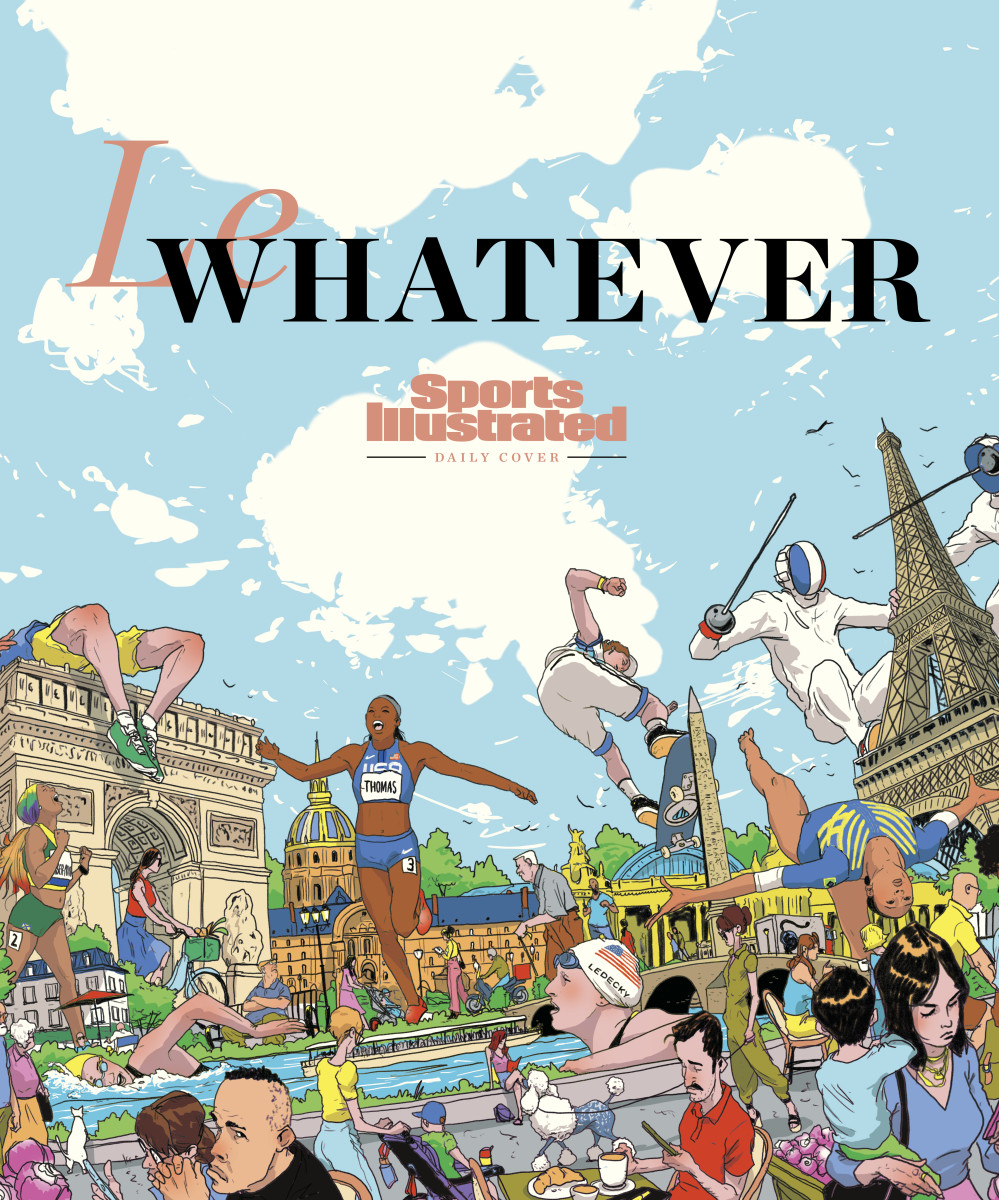

Paris 2024 Is One Year Away. Do the French Care?

For the past few Olympic cycles, some of the most suspenseful races have come before the opening ceremony. The event has no formal designation, but it distills to something like this: Can the host city get its act together and scramble to finish off its ambitious preparations before facing international embarrassment?

On the eve of the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia, local officials were still rounding up stray dogs while doors were being affixed to hotel rooms and plumbers were installing toilet seats in the athletes’ village. In the hours before the Rio Games began in ’16, workers were fixing gas leaks and repairing the recently collapsed main ramp of the sailing venue.

The 2024 Games in Paris, which will commence next July 26, exactly one year from today, are unlikely to feature many of these dramatic madcap dashes against the clock. Overwhelmingly, the venues and facilities that will be used from July 26 through Aug. 11, 2024, are already in existence. There are no subway lines or street lanes or luxury hotels in need of hasty construction. Most of the city’s peerless infrastructure was already intact the last time Paris held the Olympics. Which was in 1924, an even century ago.

If there’s any apprehension in the run-up, it will come from a different source: Will the locals care? Will the folks in the brasseries and boulangeries lose their Gallic, cool remove and infuse the Games with energy and whimsy and passion?

Right now you could spend a week in Paris and then head home oblivious to the fact that the Olympics are coming to town. You’re more likely to hear chatter about the iron and lead used in the restoration of Notre Dame than about the bronze, silver and gold to be distributed one summer hence.

Take in the bottomless charms of Paris, as this reporter recently did, and you’ll see posters for art exhibits and photo shows and operas and Bruce Springsteen tour dates and notices for Shannen Doherty headlining some kind of manga/sci-fi convention. But nothing pertaining to a quadrennial global sporting event. If locals mention Paris 2024 at all, it’s often in the context of how much their apartments will fetch on Airbnb while they’re in Provence or Mallorca or Greece.

One of the few Paris 2024 earmarks: a modestly sized replica of the Olympic rings adorns the Hôtel de Ville, the city hall. And a few blocks away, the Forum des Halles mall is the site of an “Official Olympic Boutique” pop-up shop. There, one could buy a plush toy in the image of the Games’ mascot, Olympic Phryge, a fiendishly doe-eyed anthropomorphic red hat, for roughly $45. Could. But not many do. The store is run by one worker who spends considerable time on his phone, wearing the national look of boredom, as Whitney Houston plays on the loudspeakers.

Yet for all of this—to pick a few French words, nonchalance? Insouciance? Ennui?—one could argue that there is not only nothing to fear, but also that this is, ultimately, for the best. And it all augurs for Olympic success of a different kind.

It has been a bit of a rough patch for the Olympic movement. China held the most recent Winter Games, an awkward affair and a strikingly regrettable—or strikingly fitting—choice to host a global event in a world already slinking toward authoritarianism. Even Thomas Bach, the International Olympic Committee’s usually cheerleading and generally invertebrate president, conceded as much: “The Olympics cannot solve problems that generations of politicians have not solved.”

Before China’s problematic hosting, the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics were held in ’21, delayed a year by COVID-19. Before that? The ’18 Winter Games in PyeongChang, South Korea, were a buzz-deprived ratings bust, at least in the U.S. and Europe. When Brazil was awarded the ’16 Olympics, the country appeared to be an emerging global superpower. When the Games arrived, the country was mired in a recession. When the Games ended, Brazil began paying off its cost overruns, an exercise that continues to this day. Which brings us back to ’14, in Sochi, where Vladimir Putin spent wildly on his exercise in Russian triumphalism (including the budget for his systematic doping campaign). During the Games, the emboldened Russian president annexed Crimea, foreshadowing the Ukraine invasion he would launch eight winters later, the day after the Beijing Games ended.

And now for the palate cleanse.

With abundant supporting evidence, the IOC stands accused of aiding and abetting acts of sportswashing, the voguish term whereby a country uses competition and gleaming stadiums to launder its image and distract from human rights abuses.

Yet the 2024 Olympics represent a kind of sportswashing in reverse. By bringing its road show to a country without human rights offenses, political repression, stifled dissent, autocratic rule or a closed internet, it is the IOC itself—not the host—that might find some reputational redress by association. This isn’t a sullied country using the Olympics to improve its image. This is a sullied Olympics using a country to decontaminate itself.

Instead of cozying up to strongmen, instead of watching an emerging country mortgage its precarious financial future on wretched sporting excess, the Games head to . . . [cue accordions] Paris, a place that hardly needs a sporting event to shore up its image or goose its tourism.

Sports predictions often come cheap. But bank on this for Paris 2024: There will be no stories of vacant white-elephant stadiums or state-run doping scandals or disastrous cost overruns. The IOC bringing the Olympics to Paris is akin to your cousin investing in T-bills, having learned his lesson after a crypto bender.

On the subject of finance, Paris will spend between $4 billion and $5 billion in the staging of the Games, which sounds like a lot. But it’s about a third of the final bills for Rio 2016 and Tokyo ’20 and is downright stingy stacked up against, say, the $50 billion Russia committed to the Winter Games a decade ago, never mind the $220 billion Qatar invested in infrastructure and construction hosting the men’s World Cup last December. Plus, more than 95% of the Paris ’24 expected costs will be covered by the IOC, sponsorships and games revenue. Premium partnerships have been fetching in the neighborhood of €100 million (roughly $110 million).

Paris 2024 isn’t just doing this on the cheap. Its austerity was part of the pitch, both to the IOC and to the French citizenry. Officials have gone so far as to brag that reducing the number of torches used in the torch relays will be a cost savings (and environmental benefit). Again and again, President Emmanuel Macron has stated flatly, “There will be no Olympic tax.”

Nor should there be. The construction costs for new facilities are minimal. And existing facilities will be used creatively and economically. The only permanent structures being built: the Le Bourget Sport Climbing Venue and the aquatics center, which, after the Games, will benefit Seine-Saint-Denis, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. A number of facilities are temporary and will be disassembled after the Games. In service of efficiency and economy, other venues will hold multiple events. For instance, Roland Garros, home of the annual French Open, will host tennis, yes, but also boxing.

“Everything is on budget,” says Etienne Thobois, CEO of the Paris Organising Committee and a French badminton player at the 1996 Atlanta Games. “The resources on the revenue front is going well. The ticketing program is so far a great success. The sponsorship, on its way; almost 90% of our revenue target is already achieved. So all in all, we are pretty in a good place, right where we want to be coming into the home stretch.”

As host, Paris will, inevitably, be analogized to London, home to the 2012 Summer Games, which were, incontrovertibly, an overall success. Two cities, bracketed together in the best of times. Barely two hours apart by train. Both having hosted the Games twice before.

But the comparisons between 2012 and ’24 go only so far. In the case of London, organizers took an entire part of town, the docklands known as Canary Wharf, and turned it into an Olympic Village, studding it with new venues and housing for thousands of athletes, helping load up the Games’ tab to a dramatically over-budget $15 billion. Not so Paris. Inasmuch as there will be a vital center, it will be in Saint-Denis, a suburb nine miles north of the Eiffel Tower, where the Olympic Village will be within walking distance of the Stade de France, the venue for track and field events as well as rugby.

But the pulsing heartbeat for Paris 2024 will not be confined to a village, but rather (and quite intentionally) diffused throughout the city, if not throughout the erstwhile French empire as a whole. (Sailing will be held on the Mediterranean in Marseille; surfing in Tahiti, French Polynesia.)

The 2024 Games will make clever use of Paris’s public spaces and landmarks. Jerry-built behind the Eiffel Tower, a temporary stadium will host beach volleyball. A few hundred yards behind that, a temporary Grand Palais will host judo. A short walk away, archery will be held in front of the Hôtel des Invalides, home to French military museums and the tomb of Napoleon. A brisk mile walk from there, La Concorde, the square in the heart of the city, will host “urban sports” like BMX freestyle, breaking, skateboarding and 3x3 basketball events.

From hotels and apartments in the center of Paris, fans and spectators will be able to walk (or bike) to most of the venues. Paris’s subway and mass transit system, the Metro, is as good as any in the world. Cars will be largely obsolete. Local organizers already brag that these Games will enlist 40% fewer vehicles than London’s. The organizing committee scarcely issues a press release without using the word sustainability.

The real star attraction of the Games, however, will be the great Parisian secret hidden in plain sight. The Seine wends its way through town, cleaving Paris before heading northwest and eventually emptying into the English Channel. From a distance, the river is greatly romantic. Up close, not so much: a repository for discarded wine bottles, Orangina cans, bicycles, sewage and so many pollutants it is unfit for most fish, let alone humans.

Beyond sustainability, organizers are promising improvement: As part of their bid to the IOC, the Paris Olympic Committee and Paris’s long-serving mayor, Anne Hidalgo, vowed that the Seine would be decontaminated to the point it would be fit to host events. And as part of the effort to gin up local support for the bid, organizers promised that the Seine would stay sufficiently clean that Parisians could swim in the river (legally) for the first time in a century.

When France hosted the 1900 Olympics, seven swimming events were held in the Seine. But by the 1924 Games, the river had already been deemed too polluted for human use. A swimmable Seine has long been a promise unfulfilled by too many political candidates to list. But soon after the IOC picked Paris, the city sunk more than $1 billion into a complex project to clean up the river. (The city may even be trendsetting. Time reported recently that Los Angeles, host of the 2028 Games, has sent water and sanitation officials to Paris to see what lessons can be learned for the L.A. River.)

The plan is less about purifying the river than treating waste and creating elaborate pipes, pumps, tanks and channels to reroute discharge and bacteria. Locals are skeptical that “the swimming plan” will come to fruition and that, by 2025, there will be public pools implanted in the river. But as promised, the Seine will figure prominently in the Games. Instead of holding the opening ceremony in a stadium, Paris ’24 will commence with a pageant on the river, with more than 100 barges and boats filled with athletes, drifting for six kilometers past an anticipated 600,000 onlookers assembled on the banks and on bridges.

Then, open-water swimming and the triathlon will not only be held on the Seine, but also will be open to the public.

“One thing we’re quite proud of is that we were able to maintain a complete support with the Games at every kind of level. The general public has been consistent from the start, which was not always the case in prior Games,” says Thobois. “Maybe the biggest surprise is that we [haven’t yet had] such a big surprise.”

Next summer there will be snags. There always are. Organizers have already increased the budget by €400 million, half of which has been attributed to energy price spikes caused by the war in Ukraine. Top committee leadership has churned, as officials sniped at each other. And a June police raid on the Paris 2024 headquarters as part of an investigation into corruption in the awarding of public contracts raised deep concerns. But largely, the Games are on track. Organizers tout that more than 6.8 million tickets have already been sold, roughly two-thirds of the overall inventory, even if a healthy chunk of the buyers have been British and American.

There is an inescapable sense that, after years of turmoil and scandal, the Games are in mature, steady, responsible hands. And that local excitement for these artisanal Olympics will arrive eventually. In keeping with the national character, it will just show up fashionably late.