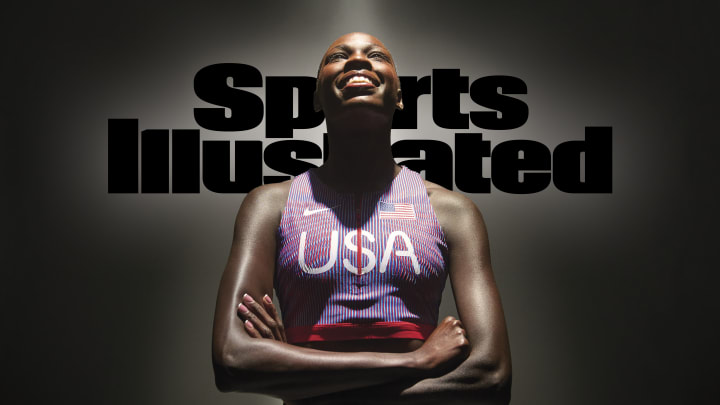

Athing Mu Is Back on Track for the Paris Olympics

Days turned into weeks that stretched for months, and, still, Athing Mu didn’t want to run. She had always wanted to. Run harder, run faster, run past every competitor in sight. Not running equated to not breathing. As she glided around tracks with graceful strides—eyes widened, mouth agape, often smiling while dominating—she presented an ideal, a person born to do exactly what they were doing, better than anyone else in the world.

That she was prodigious, medaling at the biggest, toughest races before she could legally order an alcoholic drink, only made all she accomplished seem easy, predestined. From her hometown of Trenton, N.J., to a worldwide stage in Tokyo, Mu set a slew of NCAA records and, in 2021, snagged a pair of Olympic golds, in the 800 meters and 4x400-meter relay. She followed it up with a world championship medal the next summer. Nike sponsored her. She dabbled in modeling.

Everything seemed perfect. But nothing that perfect lasts.

Weeks before the 2023 world championships in Budapest, Mu prayed she could stay home. She didn’t want to run. Just the idea of running made her anxious. She decided not to enter races or withdrew from them. Her coach, Bobby Kersee, told the Los Angeles Times a few weeks before the worlds in August 2023 that “the next time [Mu] gets on the plane it’ll either be on vacation or to Budapest.” The very thing that once freed her now filled an existential dread.

The joy that defined Mu, in the best and most obvious ways, came from running, until it didn’t. Her agent, Alliance Sports Management CEO Rocky Arceneaux, noticed a change—in mood, temperature, day-to-day bearing—about three months before the worlds. In hindsight, Arceneaux wishes he had addressed concerns earlier and more directly, like he might have, he says, with one of his NFL clients, such as Ja’Marr Chase or Ezekiel Elliott. Instead, he hesitated.

Mu didn’t skip the worlds. She couldn’t, not as the reigning Olympic and world champion in the 800. She won her first heat, then fell 475 meters into her semifinal before rallying to qualify for the final. She even paced that medal race, until the strangest thing happened in the last 300 meters. Kenya’s Mary Moraa passed her en route to first place. So did Great Britain’s Keely Hodgkinson, Mu’s chief rival, to finish second.

The plummet from Olympic gold to world championship bronze was unsettling. It happened in an instant and the result left her greatest love dimmed. “There’s so much pressure overall,” she told reporters in Hungary. “You’re overthinking … you know, the past few years have been a lot.”

Arceneaux and Kersee met with Mu immediately. This wasn’t quite an intervention. But it was necessary, serious. They started with the truth. They knew that she was struggling and that something wasn’t right. “Are you O.K.?” they asked, meaning her, the human.

Mu shook her head. No. “She has always been an elite runner. She did everything with such ease and style. She was glamorous,” Arceneaux says. “I don’t think she realized the world stage she was on.”

Hence the hunt that followed, with Mu searching for what she lost, the same thing that powered her faster and faster: joy. It felt like her career had split in half. The fun part, the dominant, on-the-rise, broken-record-collecting portion seemed over, already, by age 21. The not-fun part, the serious, weighted-down, can’t-lose portion, had taken hold. She needed to merge both halves, find peace and speed simultaneously. But … how?

The Paris Games were only 11 months away.

Mu reached peak joy in Tokyo, at those Olympics, where she sprinted across the widest, grandest stage of her career. On Aug. 3, 2021, she became the first American woman to win 800-meter gold at the Games in more than half a century.

She came to understand where that started, with her mindset, the absence of unnecessary internal expectations. In Japan, Mu never considered any race beyond her next one. After qualifying for the final, she told herself, Well, may as well win.

This approach—low expectations yielding staggering dominance—made for an ideal bubble. Mu ran as if immune to pressure, ran because of how it made her feel, giving her purpose and forming her identity. She didn’t start out running for money or fame. She ran to win. Because it felt good. Because she could.

Mu loved existing inside that bubble, happy and fast, each attribute powering the other. After her individual triumph in Tokyo, she was asked to join the 4x400 relay team, a powerhouse of elite athletes including Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone and Dalilah Muhammad, formed to bolster the unprecedented medal tally of soon-to-retire Allyson Felix, long the face of U.S. track and field.

Tasked with anchoring the final, Mu grabbed the baton with a sizable advantage, then took off as if shot from a cannon. Broadcasters pronounced the race “all but over” before she sped through the first turn. Her advantage grew, widening until Mu seemed to be sprinting all by herself. “This is when she’s most beautiful and most dangerous,” the commentator said.

“That was like an All-Star team,” she says. “We’ll never have that again. I mean, we’ll have that again. But it won’t be in the same realm as what it was.” She pauses. “The fact that I anchored was just, like … man, I was running for my life.”

She finished that race roughly 50 meters ahead of anyone else.

She was 19—on top of her sport, on top of the world. But majestic success created new problems she never anticipated. It changed her paradigm, this remarkable Olympic performance; the best moment of her career more like a steak knife pointed toward that ideal bubble and … pop.

Mu grew up in New Jersey’s capital city, the second youngest of seven children and the first born in the U.S. Her parents and her five older siblings had fled their war-torn homeland in what is now South Sudan and settled in the Garden State near relatives. The Mu (pronounced moe) kids traveled as a group, whether to school or church on Sundays. But only two runners separated from the familial pack.

Athing (pronounced uh-THING) joined the Trenton Track Club at age 6, following her brother Malual, who is two years older and ran at Penn State. The Mus sometimes struggled financially. While family was her foundation, running faster and faster became her escape.

At 16, Mu broke the U.S. record for an indoor 600-meter race. In 2021, she set the U-20 world indoor record in the 800 meters. Offers to turn pro started to flood in. Mu wasn’t ready, not yet.

No matter how fast she ran, Mu always managed to find more speed. At Trenton Central High, where she played tenor sax, made the honor roll and won a seat on the student council, she tried to have half of a normal existence: She devoured Grey’s Anatomy, dabbled in photography and interior design, joined the volunteer club. But she wasn’t normal on the track; she competed for a club team rather than her high school. She needed the competition. She enrolled at Texas A&M on scholarship, set the NCAA outdoor 800 mark and ran the second-fastest 800 ever as a freshman. “I was at peace with myself,” she says. “I’m blessed with this gift. I can’t take it for granted. I’m here for a reason.”

Sure, she had watched the Rio Games as a 14-year-old and thought, I want to be an Olympic champion. But that quickly? At 19? Mu didn’t think like that. “We were just normal,” she says. “Normal, ordinary youth club.”

Normal meant joy. And joy meant speed.

Winning had never been Mu’s problem. Winning too often would be.

When Mu qualified for the Tokyo Games, local officials hung a banner outside city hall in Trenton. Many prepped for Olympic viewing parties and celebrated her as theirs, as them. Mu delivered, but in delivering, she paid a higher-than-expected toll.

Two years after the Olympics she let slip in one interview what she had known, inside, ever since those magical Games concluded. This pressure was different. She had always embraced the gravity of competition but needed time to adjust to the unfathomable stress often baked into greatness, all the eyeballs and attention, flashing lights and clicking cameras, not to mention the negativity swamps known as social media. Skeptics—there weren’t many, but enough to catch her attention—began circling, especially after her performance at the worlds.

Overwhelmed, she focused on the negative aspects of excellence, standards now so high they seemed impossible to meet. She wasn’t some top-five NFL draft pick. She was a track star, a big deal in a niche space, largely ignored by mainstream sports fans outside of Olympic years. But breaking through the track bubble, sprinting so fast as to attract year-round attention, didn’t make things better. It made things worse. “It goes beyond just being a great athlete,” Mu says. “Because, again, there’s expectations, there’s pressure; just eyes being put on you.”

“My vision, early on, used to

be so small,” says Mu. “Now I see

the bigger picture. I’m going to

appreciate this more.”

Whether she could take the figurative baton from Felix, becoming not just a face of the U.S. team but the primary one, no longer seemed like a fair question. Felix’s legacy was defined by longevity, consistency over not years but decades. And there was Mu, fracturing, cracking, fed up—after a single, exceptional Olympics.

“She was,” Arceneaux says, “in a space where it weighed on her.”

Instead of running with joy, like she once did, Mu grew more and more serious, then more and more dark, the sentiment never clearer than in Budapest.

It was time for a break.

She started off with a real vacation—no running, no tracks. After the 2023 worlds she went back to Trenton, back to family and a simpler life, her commitments slimmed way down. She visited a sibling in North Dakota. She felt safe in both places, found comfort there. Mu got off social media, replacing online trolling with supportive, familiar voices. She read the Bible and prayed daily. She took walks, slowing down. She’d never done that before.

The break, she says, formed one long, deep breath.

Twice, while shopping in Santa Monica, strangers stopped her. One congratulated Mu on her performance in Budapest. The other asked if he could hug her, and … of course he could! “We don’t care how you do; we just love you,” he said, with no idea how much she needed his support. Those positive interactions underscored her ratio of supporters to skeptics. Mu had been focused on the wrong people, the infinitely smaller segment.

Every day, she felt a pinch more centered, more grounded. She started to see that stretch for what it was—a time of transition, rather than a referendum on her track soul.

She still wanted to win, break records and run faster than ever before. She still wanted to define her career by all she could accomplish. But Mu realized she ran fastest and won most when she ran happy. Worrying about all the ancillary nonsense only made winning harder, less jubilant. She shaped her new training schedule with intention: She would train year-round, but also build in regular breaks.

Soon, Mu sensed the return of “my true self.” In the months and weeks that followed, the sadness infiltrating her joyful existence dripped away. Hope returned. Nerves dissipated. She came to view what she overcame as central to her growth. She returned to a more pragmatic approach, running like that 6-year-old in Trenton ran. When she did that, dominance no longer powered her search for purpose and fulfillment.

After the 2023 worlds, Arceneaux arranged a call with a track legend, one who happens to be married to Mu’s coach. Jackie Joyner-Kersee competed at four Olympics and won a combined six medals, half of them gold, in the heptathlon and long jump. Joyner-Kersee reminded Mu that all the greats lost, slumped or, in the absence of either, faced increasing public pressure borne from lasting success. The youngest among them, like Mu, were more likely to suffer from that. But fearing that experience wouldn’t do Mu any good.

Mu would finish last season, Joyner-Kersee told her, showing their world “exactly who you are.”

Once she was back on track, Mu had to get back on the track. Her coach suggested she run in a meet she hadn’t even thought about entering. She sent one teammate a text message, asking that they pray. She entered the Prefontaine Classic last September, a surprise to nearly everyone in her sport given how sparingly she had run in 2023. She then set a blistering pace, jockeying with Hodgkinson for positioning and then passing her rival on the final straightaway. She won, holding onto first in a race where the top three women each broke their national record, including Mu, who finished in 1:54.97.

In December, on a Zoom call, with the Olympics only seven months away, Mu sounded transformed. “I can see everything that’s happening around me,” she said. “My vision, early on, used to be so small. Now I see the bigger picture. I’m going to appreciate this more. Oh, my God, I have so much gratitude. I’m just so happy—for, like, everything that’s getting ready to come, what’s right at my feet. I’m just happy to be able to run again.”

Mu knows who she’s running for and who she’s not. She trusts her coach and their training. She has never been more consistent, more level, more balanced. Her relationship to track has never been stronger or healthier. Arceneaux noticed Mu was running with joy again, that style of competing, he says, “that makes her adorable and why fans will fall in love with her” this summer, when the Games unfold.

“The best part is,” Mu says, “I’m enjoying it in a different way, not on a bad roll but genuinely, like, happy.”

Every day since Budapest has pointed Mu toward Paris. She rested for the Olympics, trained for the Olympics and dreamt of the Olympics. But throughout, she also lowered her expectations. She continued to stay off social media. Continued to break when necessary. Sure, the nerves and anxiety still occasionally bubbled to the surface. And when they did, Mu told herself, “Who cares? I’m ready again.”

Ready to compete. Ready to win. Ready to fall. Doesn’t matter. Never did.