Antonio Conte makes immediate mark in turning Chelsea back into a champion

First Leicester came from a 14th-place finish the season before to win the Premier League title; now Chelsea has come from 10th to do so. It would be lovely to hail this as a new age of egalitarianism, when everybody in the Premier League has a chance of lifting the trophy, but with Chelsea, this season represents what an outlier last season truly was. The question is not how on earth did Chelsea become so good, but how on earth did it get that bad in its 2014-15 title defense? Antonio Conte’s achievement in picking up a side that had lost its way, in his first season in English football, is remarkable.

The decisive moment came at the Emirates in late September. Conte, who had a clear preference for a high-pressing game and who had tended to use a back three both with Juventus and the Italy national team, had started the season trying to accommodate himself to a squad that had seemingly been put together with 4-2-3-1 in mind.

Watch: Chelsea wins Premier League title on Batshuayi's late goal at West Brom

He had begun with three fairly routine wins, but Chelsea had then been unfortunate to draw at Swansea. That seemed to provoke a crisis on confidence. It was overwhelmed in midfield by Liverpool at home and lost 2-1. Then it went to Arsenal.

Arsene Wenger finally achieved a decisive victory over rivals that have tormented him for so long, but it turned out he won not widely but too well. Arsenal’s superiority stung Conte into radical action. By halftime, Arsenal led 3-0 and was in total control. To stop the bleeding as much as anything else, Conte switched to a back three. That change effectively won the league.

Soccer Managers: When they were players

Antonio Conte, Chelsea

Antonio Conte celebrates a goal for Juventus against Rangers in the Champions League in 1995.

Carlo Ancelotti, Bayern Munich

AC Milan's Carlo Ancelotti, right, goes head-to-head with Napoli's Diego Maradona when both played in Italy in October 1990.

Diego Simeone, Atletico Madrid

Argentina's Diego Simeone shakes hands with England's David Beckham after their match at the 2002 World Cup, four years after Beckham was sent off for kicking out at Simeone.

Diego Simeone, Atletico Madrid

Diego Simeone celebrates scoring a goal for Lazio against Vicenza in a Serie A match in April 2001.

Jurgen Klinsmann, U.S. men's national team

Jurgen Klinsmann celebrates after scoring Germany's lone goal in a 1-0 win over Bolivia in a 1994 World Cup match in Chicago.

Jurgen Klinsmann, U.S. men's national team

Jurgen Klinsmann celebrates after scoring the first Stuttgart goal in the 1989 UEFA Cup final second leg against Napoli in May 1989.

Jurgen Klopp, Liverpool

Jurgen Klopp, right, makes a play on the ball while playing for Mainz against St. Pauli in 1999.

Luis Enrique, Barcelona

Luis Enrique scores for Barcelona against Arsenal in the group stage of the Champions League in October 1999 at Wembley Stadium.

Mauricio Pochettino, Tottenham

Argentina's Mauricio Pochettino takes down Engand's Ashley Cole in the group stage of the 2002 World Cup in Japan.

Joachim Low, Germany

Joachim Low, playing for Karlsruher against Werder Bremen in a November 1984 Bundesliga match.

Patrick Vieira, New York City FC

While starring at Arsenal, Patrick Vieira goes head-to-head with a young Cristiano Ronaldo in the Gunners' win over Manchester United in the 2005 FA Cup final.

Pep Guardiola, Manchester City

Pep Guardiola mans the midfield for Barcelona in a February 2001 match against Athletic Bilbao.

Pep Guardiola, Manchester City; Zinedine Zidane, Real Madrid

Pep Guardiola stands side-by-side with Zinedine Zidane in a Euro 2000 quarterfinal between Spain and France.

Zinedine Zidane, Real Madrid

Zinedine Zidane escapes away from Michael Ballack in Real Madrid's 2002 Champions League final triumph over Bayer Leverkusen, in which Zidane scored the winning goal.

Zinedine Zidane, Real Madrid

Zinedine Zidane led the European All-Stars, while Brazil's Ronaldo led the World All-Stars in a star-studded match in France prior to the 1998 World Cup draw.

Didier Deschamps, France

Didier Deschamps lifts the Champions League trophy with Marseille after captaining the squad to a triumph over AC Milan in 1993.

Ronald Koeman, Everton

Ronald Koeman, front, celebrates after scoring the winning goal in the 1992 European Cup final for Barcelona against Sampdoria at Wembley Stadium.

Andriy Shevchenko, Ukraine

AC Milan's Andriy Shevchenko, right, is mobbed by Clarence Seedorf and Kaka after a goal against city rival Inter Milan at the San Siro in 2004.

Chelsea won its next 13 games–a Premier League record for consecutive victories within a single season. It was top of the table by early November, and, despite a couple of wobbles recently, it has never really looked like surrendering that position, becoming the first side since Everton in 1962-63 to win the championship using a back three in most games. If it beats relegated Sunderland at home next weekend, it will be only the sixth side in history to reach 90 points for a 38-game season.

The back three, usually protected by N’Golo Kante and Nemanja Matic–although Cesc Fabregas has played there in games Chelsea has expected to dominate–has been decisive. Many mocked the return of David Luiz to the club–and Conte himself seemed skeptical–but protected by two other defenders, the Brazilian has excelled. With the double cover of Cesar Azpilicueta and Gary Cahill, the fact his positional sense sometimes deserts him becomes less relevant, and his natural physical assets and ability on the ball have flourished. Victor Moses, pressed into service in an unfamiliar position at right wingback, and Marcos Alonso have been tireless, offering attacking width as well as defensive cover.

The greatest impact of the 3-4-2-1, though, has come at the other end of the pitch. With a solid platform in the center and players overlapping in wide areas, the two players in the three-quarter line occupy awkward pockets, outside the opposing defensive midfielders, inside the opposing fullbacks, and in front of the opposing central defenders. Pedro and, particularly, Eden Hazard have thrived there: Hazard has scored 15 goals and set up five, while Pedro has scored eight and set up eight. The Belgian, such a disaffected presence last season, is perhaps the most obvious example of the impact of Conte on morale.

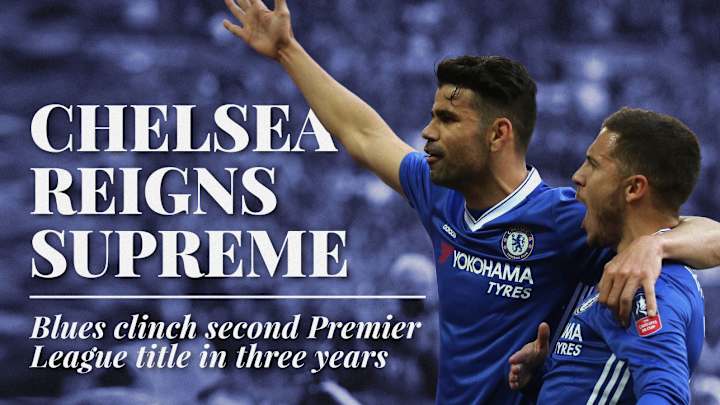

Diego Costa, meanwhile, has been his usual awkward, cussed self, leading the line, riling defenders and occasionally conjuring goals from nowhere, although his level has dipped since January. For all the elegance of its team play, one huge advantage Chelsea has had this season has been its capacity to score goals out of, well, the blue. When games seemed to be drifting–at home to West Brom, away to Middlesbrough, away to Crystal Palace–he had a habit of generating goals largely by dint of being Diego Costa in the right areas, forcing mistakes, quickly coming up with half-chances.

It’s Kante, though, who has been Chelsea’s outstanding player, a deserved recipient of both the players and football writers’ Player of the Season awards. Such is his work rate and position that Hazard commented that playing like him is like playing with twins. Leaving aside the strange netherworld of the reserve goalkeeper, he is the first player to win the league with different clubs in successive seasons since Eric Cantona (Mark Schwarzer "accomplished" the feat with Chelsea and Leicester in the last two seasons, though he didn't play a single minute of Premier League football in either campaign).

N'Golo Kante: The Premier League's silver bullet

The change of shape, though is not the only reason to praise Conte. Hazard spoke of the increased “automization” of Chelsea’s play since Conte, via the Guus Hiddink interregnum, replaced Jose Mourinho. The Manchester United manager is a master at organizing a defense but imposes nothing like the same level of systematization in attack.

Conte, though, is a devotee of shadow-play–that is, playing without an opponent to get the shape right–of practicing set moves to adapt and apply in practice. Without the distraction of European football, he has been able to spend hours on the training pitch, taking his players through positional drills. The effects have been obvious, particularly in those lightning counters in the games away at Manchester City and West Ham.

Kante, Hazard and Diego Costa have all been outstanding, but more than most this is a success born of the manager. Conte’s positivity and purposefulness soon cleared away any lingering toxicity from the final days of Mourinho’s reign, and he has come up with a tactical plan that the rest of the league has struggled to counter.

This is Conte’s triumph.

An accomplished author of multiple books, Jonathan Wilson is one of the world’s preeminent minds on soccer tactics and history.