Memorable Firsts in NASCAR

Memorable Firsts in NASCAR

In just its second year of existence as a sanctioning body, NASCAR introduced its newest division, "Strictly Stock," on June 19, 1949, on a three-quarter mile dirt track in Charlotte. Glenn Dunaway crossed the checkered flag first in his Ford, but was disqualified after officials noticed he had tampered with the front springs. That gave Jim Roper (inset) his one and only NASCAR victory in a Lincoln, collecting $2,000 for his troubles -- about the cost of one set of racing Goodyear tires today. (Send comments to siwriters@simail.com)

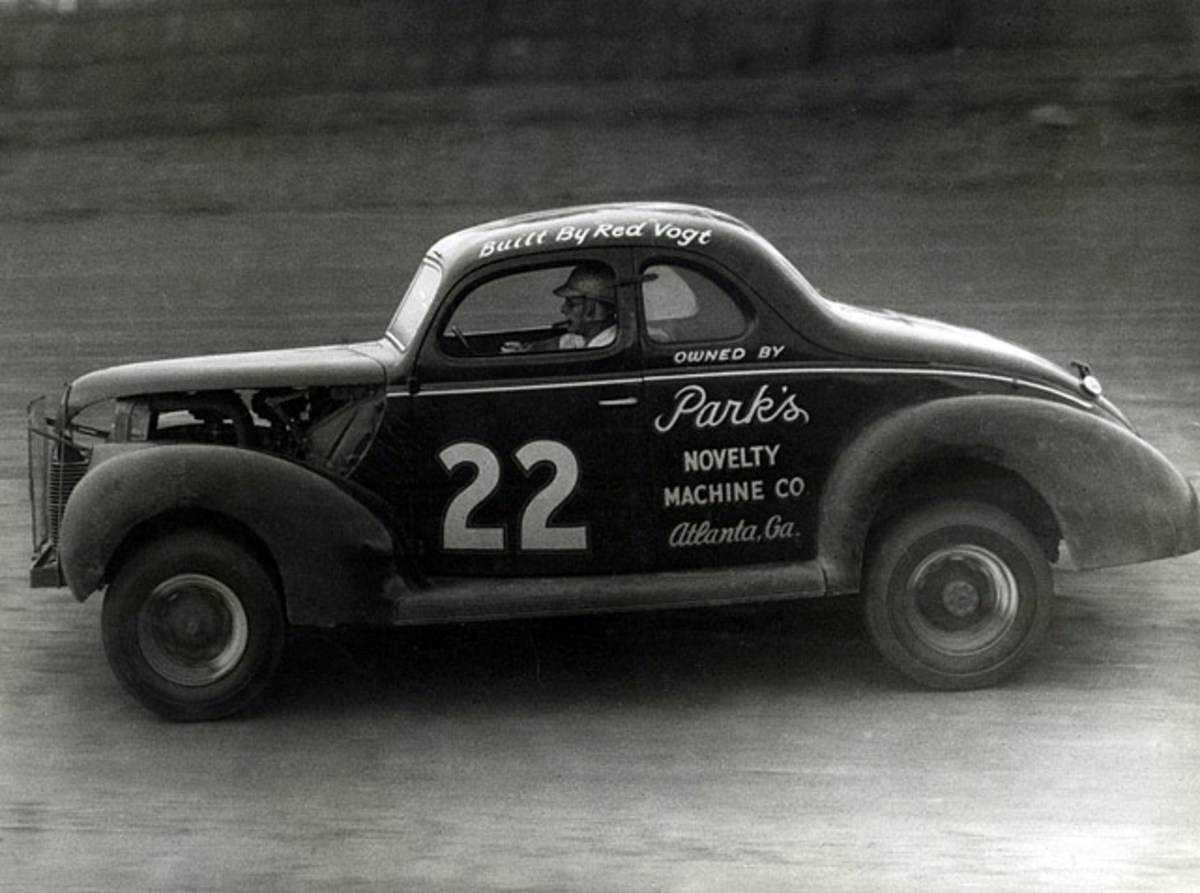

A former tail-gunner during World War II, Red Byron was shot down over the Aleutian Islands and nearly lost his left leg. After two years in military hospitals, he initially needed it bolted to a steel stirrup on the clutch just to press both pedals to race. But by 1949, he'd become the ultimate racing success story, taking home two trophies -- one on the vaunted Daytona Beach road course -- en route to winning the season championship by 117 points over "King" Richard Petty's father, Lee. Driving for legendary car owner Raymond Parks, Byron never won a race at NASCAR's top level again, but the impressive early accomplishment leaves Byron and Parks as finalists for the sport's second Hall of Fame class in 2011.

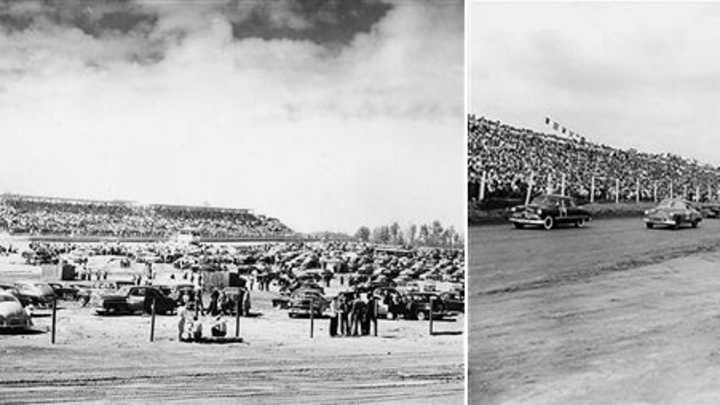

Initially known as "Harold's folly," the Darlington, S.C., project by businessman Harold Brasington was constructed on a 1.33-mile paved, egg-shaped oval in the small town during the Fall of 1949. Hoping to become stock car's home for 500-mile racing, the oval-shaped track -- built that way to maintain a minnow pond next door -- was granted a date from NASCAR a year later. Over 25,000 fans witnessed the first Labor Day Weekend edition of the Southern 500, a 75-car field bested by Johnny Mantz that started a tradition that lasted well over 50 years. Darlington remains part of the NASCAR schedule today, although its main event is contested on Mother's Day Weekend instead of in September.

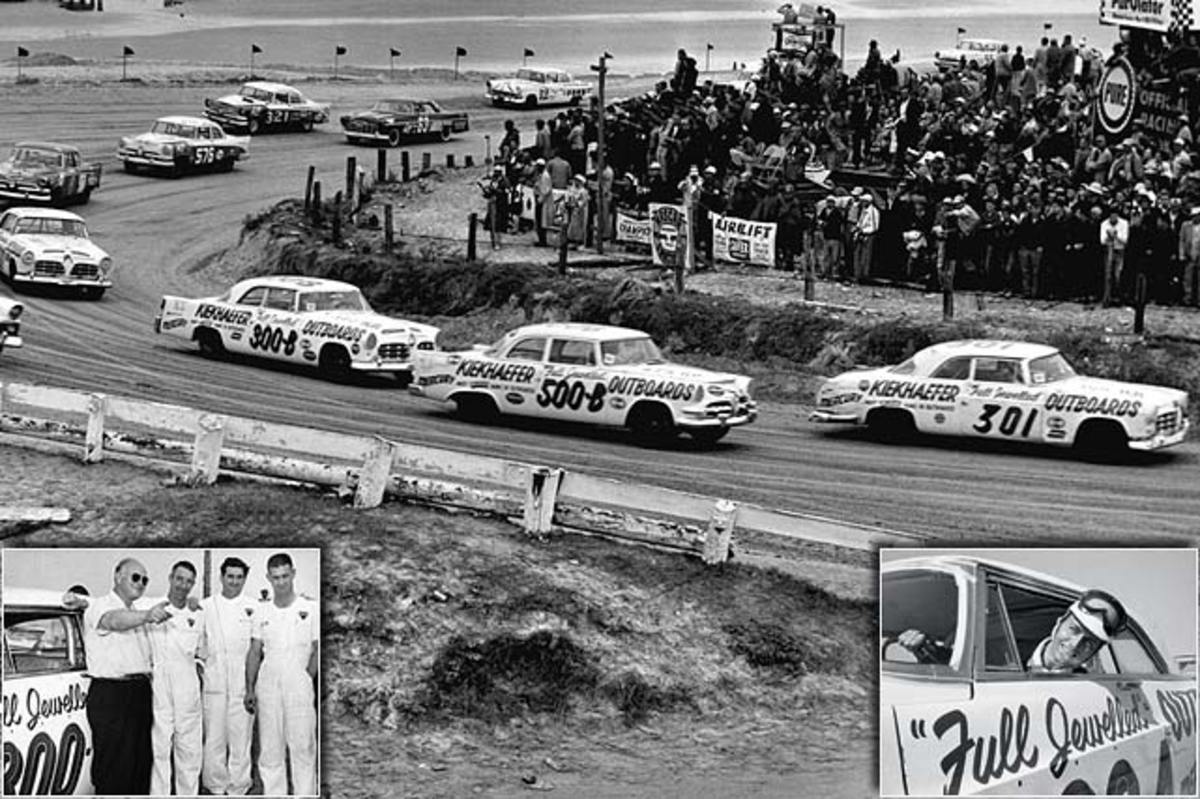

Before there was Rick Hendrick and Jack Roush ... there was Carl Kiekhaefer (left inset). In a two-year period beginning in 1955, he won an astonishing 52 times -- including 16 races in a row -- with his Chryslers and won point championships with Tim Flock (right inset) and Buck Baker, respectively. But his overwhelming dominance turned fans and fellow competitors against him, and by January 1957 he was out of the sport amidst accusations of cheating after a fallout with NASCAR's Bill France -- although no rules violations were ever found.

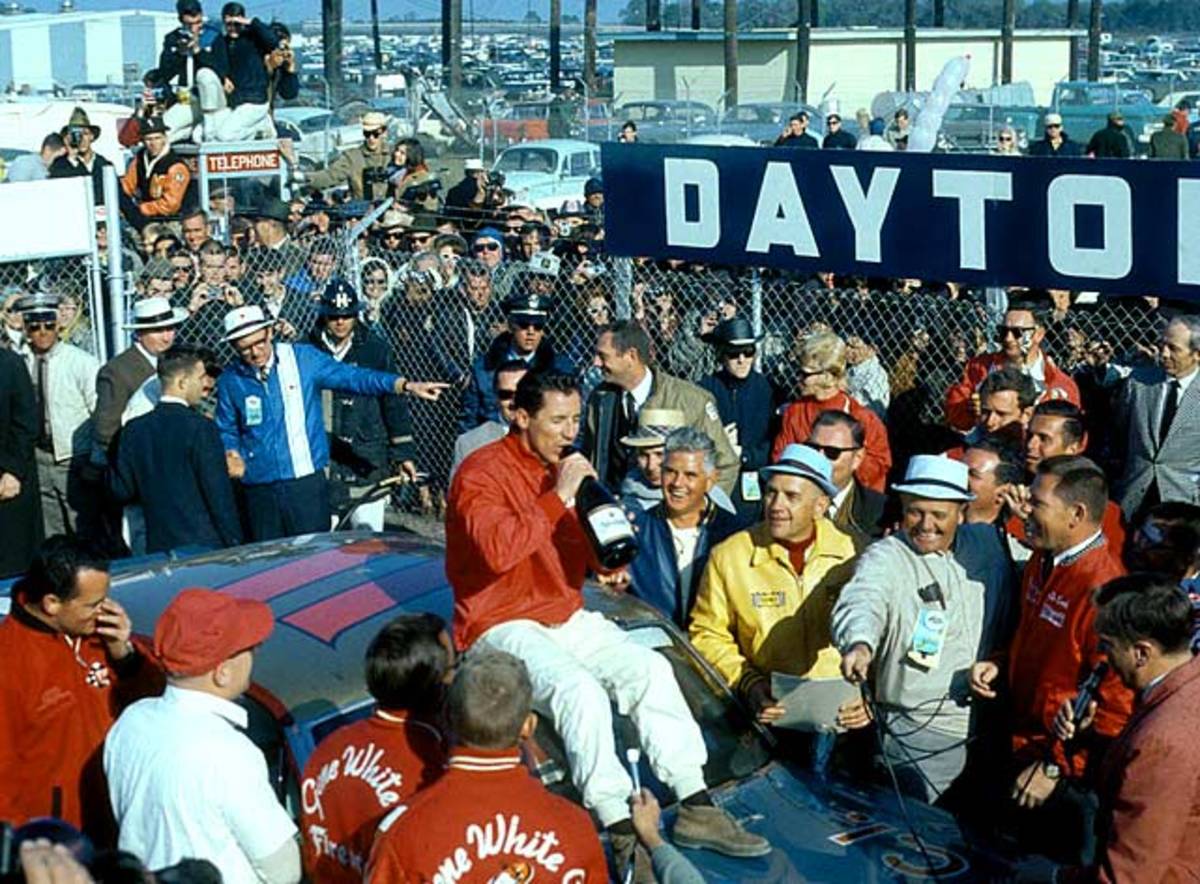

The Great American Race was started under Bill France, Sr.'s watch, a $3 million investment in a 2.5-mile oval to rival Indianapolis. The first version lived up to expectations, Lee Petty besting Johnny Beauchamp in a photo finish on Feb. 22, 1959. The race was so close, Beauchamp was initially declared the winner before France reversed the ruling three days later, using newsreel and photographic evidence to prove Petty was out in front.

NASCAR's early tangles with racism -- the Frances were once avid supporters of segregationist Presidential candidate George Wallace -- came to an ugly head on Dec. 1, 1963. In a 100-mile race on a half-mile dirt track in Jacksonville, Wendell Scott (pictured) bested Buck Baker to the line by two laps. But Baker was initially flagged the winner, a "scoring error" NASCAR reversed days later in a move some said was to keep a possibly rowdy Southern crowd from attacking the rightful victor. To this day, Scott's win remains the only one by an African-American in any of NASCAR's top three divisions.

As stock car racing began to grow in the 1960s, it attracted the interest of famous open-wheelers looking to dip their feet in some of the sport's biggest races. Each one met with varying degrees of success, but Mario Andretti was the first to score big. Driving for the legendary Holman-Moody team, Andretti led 112 of 200 laps in his Ford while coasting to victory in 1967's Daytona 500. Winning Indy two years later, he became the first man to capture American motorsports' two biggest prizes (A.J. Foyt would follow suit with a Daytona victory in 1972.)

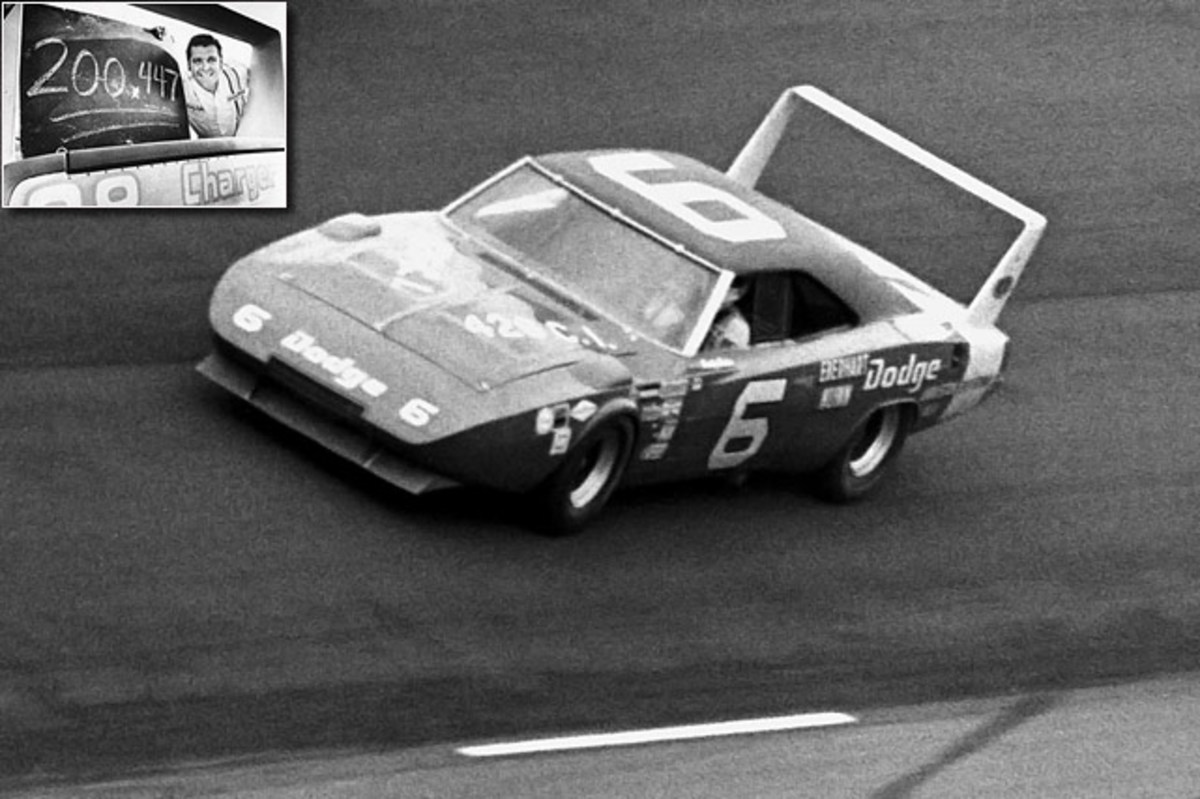

With the opening of Talladega Superspeedway in 1969, whether stock cars could break the vaunted 200 mile an hour barrier suddenly became a matter of if and not when. Buddy Baker finally accomplished the feat through the help of Chrysler Engineering, his No. 88 car posting an average of 200.447 miles an hour in a closed-course testing lap on March 24, 1970. Known as the King of Superspeedways, he'd go on to score four of his 19 career wins at Talladega while concerns over speed gradually increased through the years -- today, restrictor plates make achieving that 200 mile average a virtual impossibility.

Corporate sponsorship in NASCAR was once a bunch of small, one-time deals combined with manufacturer support to simply keep a team going from race to race. Most of the crew and even the drivers had part-time jobs outside of the sport. But with the unveiling of Bobby Allison's major sponsorship with Coca-Cola in 1970, the light bulb went off about how corporations could use these cars as rolling billboards. By 1972, Richard Petty had a full-season deal with STP and the seeds of the primary sponsorship model we see today had been fully planted.

R.J. Reynolds tobacco company was initially approached not by NASCAR but Junior Johnson, looking for someone to sponsor his race team in the late 1960s. But with a ban on cigarette advertising on TV, the company had bigger and better ideas, looking for a sport to consistently advertise its products on a national scale. By January 1972, what became a 31-year partnership with NASCAR was completed, ushering in a shorter schedule, an infusion of cash and the biggest period of growth in the sport's history.

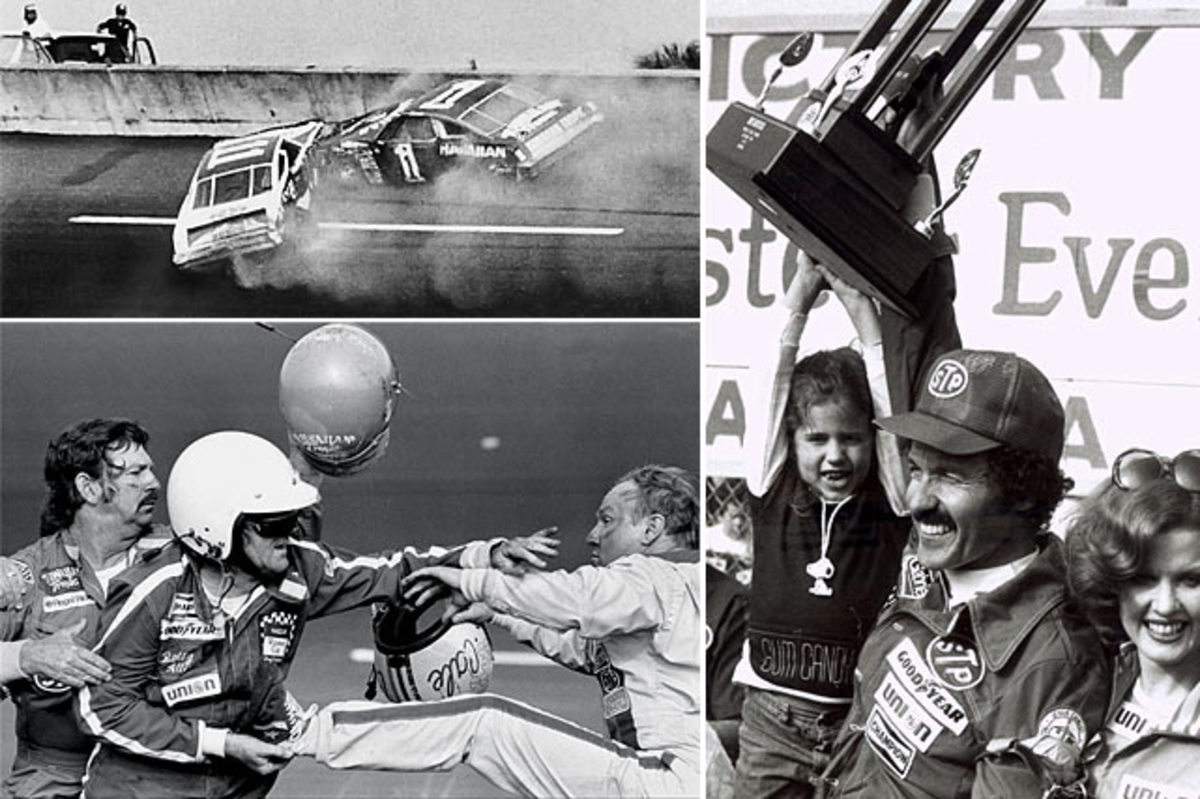

It was the snowstorm that changed the course of history. With most Americans trapped at home, a blizzard enveloping the Eastern Seaboard on Feb. 18, 1979, left many sitting by their televisions, tuning in to stock car racing for the first time ever. What they saw left them drooling for more: CBS' thrilling flag-to-flag coverage ended with the infamous "fight" between Cale Yarborough and Donnie Allison, crashing their cars on the last lap in a wreck that handed Richard Petty his sixth Daytona 500 victory. Scoring a 10.5 rating, the telecast exposed 15.1 million people to a sport many have followed ever since.

It was a Hollywood script no one could have imagined. With Ronald Reagan becoming the first sitting U.S. President to visit a NASCAR race, July 4, 1984, was already a special day for the sport. But Richard Petty winning his 200th and final NASCAR race in a thrilling side-by-side battle with Cale Yarborough to the checkers was icing on the cake. The fellow Republicans celebrated side-by-side in Victory Lane, a national image that reinforced the growing popularity of this once-Southern only sport.

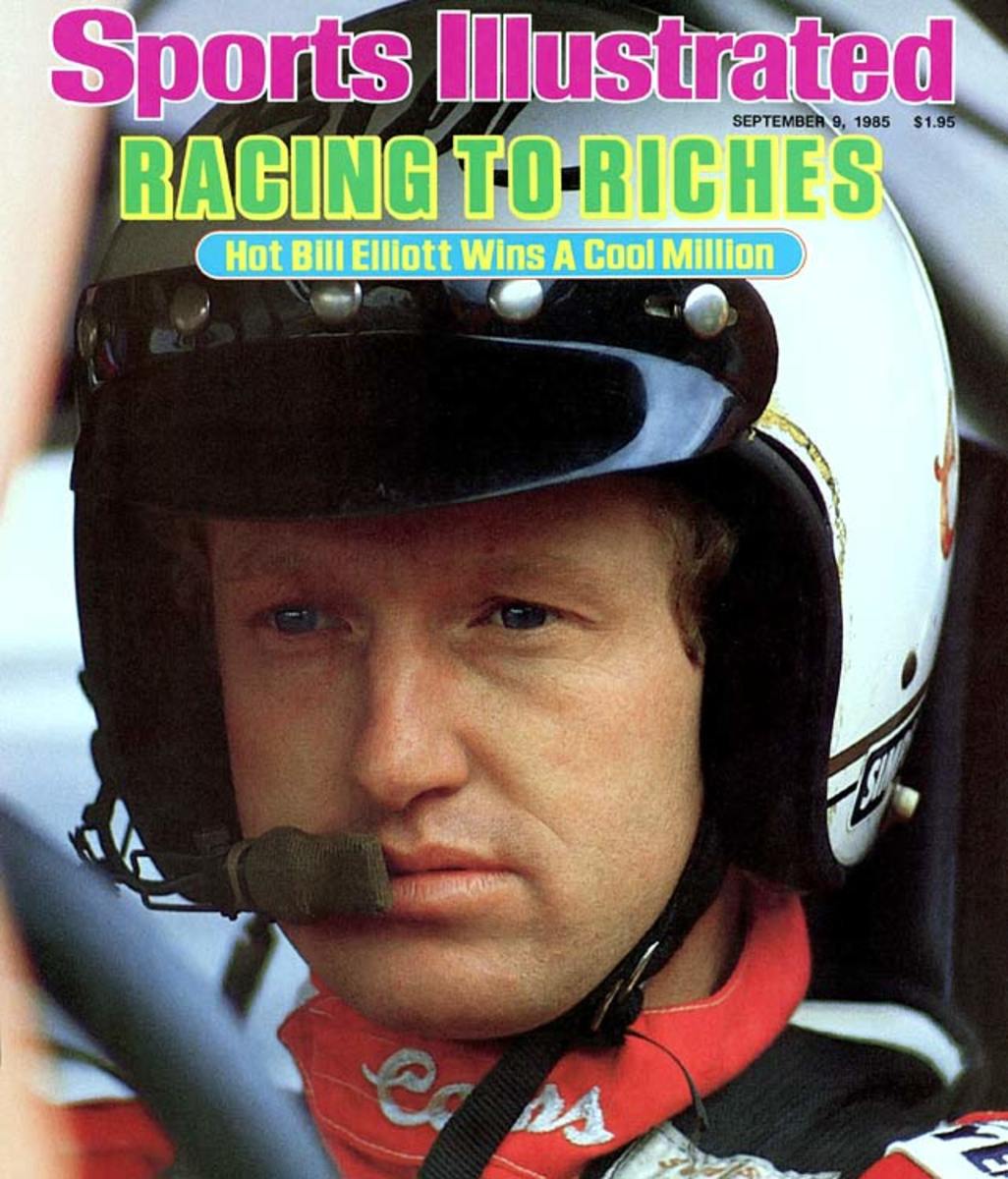

Soft-spoken Georgian Bill Elliott became the focal point of national attention during the first year of the sport's Winston Million program in 1985. Offering the million-dollar bonus to anyone who could win three of the sport's "crown jewel" races, Winston officials watched Elliott put himself in position with victories at Daytona and Talladega. After a Charlotte bid went up in smoke, hundreds of media descended on the Southern 500 at Darlington Labor Day Weekend to see if the 29-year-old could pull it off. Fighting off Cale Yarborough to the line, Elliott achieved the landmark accomplishment and landed on the cover of Sports Illustrated. The win, however, didn't give him the season championship: he lost to Darrell Waltrip despite winning a career-high 11 races.

After 83 years of hosting just one race a year, the Indy 500, the open-wheel mecca of Indianapolis opened its doors to NASCAR with a 400-mile race. A modern-day NASCAR record 86 cars attempted to make the 43-car field, the start to a two-week drama that included brothers Brett and Geoff Bodine spinning each other out during the race. When the smoke cleared, the checkers fell to hometown Indiana boy Jeff Gordon, scoring his second career Cup victory once Ernie Irvan blew a tire with fewer than five laps remaining. Within two years, open-wheel racing split in two and, just like that, NASCAR was suddenly the biggest game in town.

After 50 years of NASCAR being exclusively run by the France family, an aging Bill France, Jr. tapped Vice President of Competition Mike Helton as Chief Operating Officer in February 1999. A year later, Helton was named president and remains the top non-France family member involved in the sport, although he currently reports to Bill's son Brian, who replaced his dad as CEO in September 2003.

It all started innocently enough; after the death of legend Dale Earnhardt, car owner Richard Childress wanted to get replacement Kevin Harvick as much experience as possible. That meant while Harvick manned Earnhardt's renumbered No. 29 over in the Cup Series, Childress would keep running the rookie in a full-time schedule in the Busch Series, NASCAR's equivalent to "AAA" baseball. The experiment worked, Harvick pulling off a shocking ninth-place finish in the Cup standings (despite missing a race) while winning the Busch Series championship in a landslide. Full-time Cup drivers have found themselves "double-dipping" full-time ever since, as no Busch (now Nationwide) Series-only driver has taken home the season-ending trophy since 2005.

The sport's popularity peaked about the time four-time champ Jeff Gordon launched himself into pop culture history, becoming the first stock car driver to appear on NBC's legendary late-night show. The self-deprecating skits made Gordon and NASCAR seem like a bunch of rednecks -- but having its biggest driver on comedy's grandest stage rubber-stamped the sport as an accepted national phenomenon.

NASCAR's Chase system was met with skepticism when Brian France introduced it in December 2003, but it's hard to argue with the sport's first-ever playoff finale. Five drivers entered the final race with realistic title chances, points leader Kurt Busch leaving it a wide-open battle after losing a wheel early during Homestead's 400-miler. But the 26-year-old fought back from the brink of disaster, driving his way back to fifth to earn his first and only title by just eight points over Jimmie Johnson.

The first foreign automaker in decades to compete in NASCAR, Toyota struggled through an ugly first season with more DNQs than Laps Led. But after Toyota wooed powerhouse Joe Gibbs Racing during the 2007 offseason, everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the Camry experienced breakthrough success. Kyle Busch's Atlanta victory was the first of 10 in 36 races for both JGR and the manufacturer.

For the first four years of Jimmie Johnson's NASCAR career, he developed a knack for finding every which way to lose a championship. Now? The No. 48 team simply can't lose, locking up its fourth straight trophy last November while racking up a series-high 29 victories over that span. While Johnson has struggled through an inconsistent 2010, many oddsmakers still leave him the favorite to capture the Cup an unprecedented fifth straight time.

When Kyle Busch pulled into Victory Lane on Aug. 21, he made history as the first man to sweep three races at one track in NASCAR's top three divisions. Going 2-for-2 in Trucks and Nationwide, respectively, Busch survived a thrilling 500-lapper in Cup despite the disgust of rival Brad Keselowski, who called him "an ass" in driver intros hours after being wrecked at the hands of Busch's back bumper for the lead in the Nationwide race. The Cup victory was Busch's 78th in NASCAR's top three series as he looks to nail another first: beating Richard Petty's total of 200 Cup victories. (Send comments to siwriters@simail.com)