Davey Allison's incredible legacy lives on 20 years after his death

One night at a restaurant a few years ago, Liz Allison ran into the ex-boyfriend of a friend of hers, a man she had met before. His name was Dr. Seenu Reddy, and that night, for the first time, he told her an unbelievable story about how their lives had once intersected.

Reddy had been a medical student at the University of Alabama-Birmingham and was at the hospital the day Liz's husband, NASCAR star Davey Allison, died 20 years ago this week. As part of his medical school work, Reddy watched that day as a surgeon cut open a patient's chest and took out his heart. Reddy looked on in amazement as a machine pumped blood through the man's body to keep him alive. The surgeon took another heart off of ice and filled the man's chest with it.

That was Davey Allison's heart. His incredible legacy began when it started to beat again.

*****

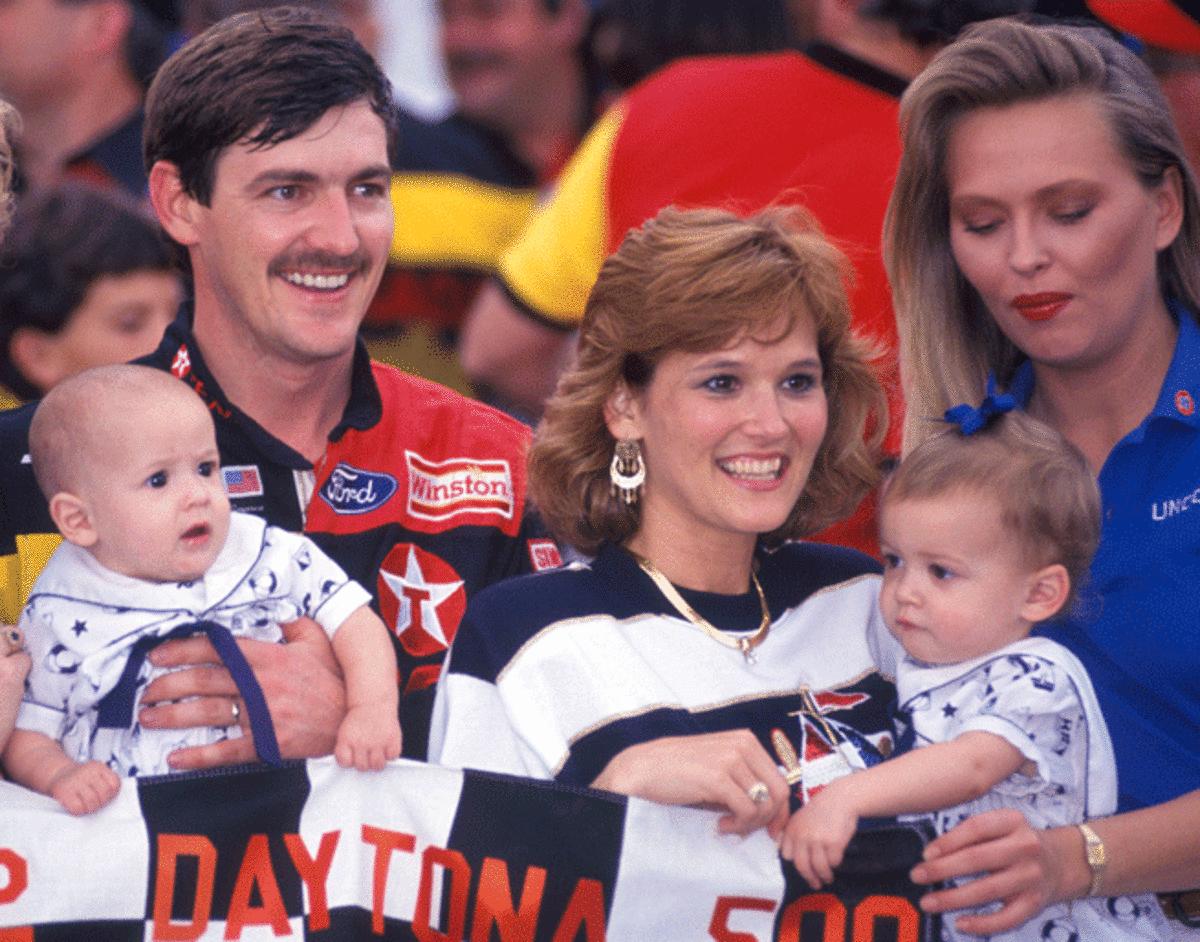

A knock on the door. A rush to the hospital. A long night pacing the halls. Crushing news. Liz Allison, just 28 years old and the mother of two young children, was going to become a widow. Her husband was going to die from the injuries he sustained in a helicopter crash at Talladega Superspeedway.

"They came in, a big group of doctors. They wanted to meet with all the family because there were so many people there," Liz Allison says in the first interview she has ever given about her husband's organ donations. "He basically said, 'Davey is dead, and would you like to donate his organs?' It was truly that cut and dry. I remember, all I could hear was the first thing he said. We all did what most do, which is drop to your knees and fall apart. He said, 'I know this is a very difficult time for you, but we have to know. It has to happen that fast."'

Liz says she and Davey had never discussed organ donation. But she knew her husband liked to give to others, and this was one last chance for him to do so. "I went back to a room with Davey's business manager [who was also his cousin and best friend], and he and I sat down together and talked about it," says Liz Allison. "Within an hour a decision was made."

Liz was given a list of organs that could be taken from Davey's body. She checked yes next to everything except the corneas. She couldn't bring herself to give those away, a decision she now regrets. "This sounds so juvenile, but all I could imagine at that time was Davey's eyes going to someone else," she says. "It freaked me out."

Tommy Allison, Davey's business manager, says he and Davey had discussed organ donation -- not a lot, but he remembers the two of them expressing amazement that it was possible after seeing a story on TV.

*****

Organ donations have come a long way since 1993, but there's still a long way to go. An average of 19 people die every day waiting for a transplant. According to Pam Silvestri, public affairs director at Southwest Transplant Alliance in Dallas, approximately 20,000 people die each year who are eligible to donate their organs. Of that 20,000, roughly 15,000 are deemed healthy enough to donate. On average about 8,000 of them are registered to do so.

Many sports figures have been recipients and donors. Pat Summerall, who died in April at 82, was a liver transplant recipient. When Bengals wide receiver Chris Henry died in 2009 after falling out of a pickup truck, his organs were donated. That same year, boxer Paco Rodriguez died from injuries he suffered in the ring, and his organs were donated. Those stories all entered the public realm because the donor family and recipients revealed their identities to each other. That never happened with Davey Allison. But not for lack of trying, at least at first.

In the immediate aftermath of her husband's death, Liz Allison wanted to meet the recipients. But the donor family's identities and the recipient's identities are kept secret from each other, and the process by which they can meet each other is often complicated and time-consuming.

There are 58 organ procurement organizations in the United States. Each has its own rules for how donor families and recipients contact each other, though those rules have much in common. If more than one organ procurement organization is involved because the donor and recipient live in different areas, it gets even more complicated.

Broadly speaking, the rules for contact in organ donation are similar to the rules for contact in adoption cases. In Alabama, if a donor wants to contact a recipient (or vice versa), he or she must write a letter. One or the other can opt out of receiving a letter, but that's rare. That letter goes first to the Alabama Organ Center to Carrie Ellis, who is the organization's donor family liaison. She strips it of identifying material and forwards it to the recipient family.

If the recipient writes back, that, too, goes through Ellis, and she again strips it of identifying material. Only after both parties sign consent forms with Ellis can they learn each other's identity. After that, the two can forge whatever kind of relationship they want to.

Liz Allison, who remarried in 2000 and is an author and radio and television personality, butted up against these rules, and against a culture within the organ donation community that wasn't as open to donor family-recipient meetings as it is now. In the past, meetings were often discouraged. They are at least treated neutrally now, and in some places they are encouraged.

Initially Liz says she was made to feel like she was doing something wrong by simply wanting to meet the recipients, never mind going through with meeting them. A few letters went back and forth between Allison and recipients. But no identifying information was shared. "I tried early on. It was something I felt passionate about. But I met so many roadblocks," she says.

She eventually gave up trying and never met any of the recipients. Today, 20 years later, she considers that a blessing. "I just don't see, at this point looking back, what good could have come from it. I'm so happy that Davey, at the time his life came to an end, that he was able through the grace of God and medicine to extend the lives of these recipients," she says. "But I know now what I wanted, and I wanted to hold on to Davey, I wanted that connection. That would have been for the wrong reasons."

The fact no meeting between Allison and any of the recipients ever took place is not unusual. Donor families and recipients remain anonymous far more often than they meet. In Alabama, 33 percent of organ donor families meet at least one recipient. In Wisconsin it's 30 percent. In Texas, it's 40 percent, says Silvestri, who is a kidney donor herself.

The relationships that follow meetings are usually good, sometimes difficult and occasionally overwhelming because of the number of people involved. Trey Schwab is a former assistant basketball coach with the Minnesota Timberwolves and Marquette Golden Eagles. He received a double lung transplant nine years ago. His donor's organs and tissue went to 93 different recipients.

Schwab has met his donor's family but understands why others don't, whether the reluctance is on one side or the other or both. "Some families, for them, it's best to just close the door, get that closure, and walk away and never revisit that again," Schwab says.

Schwab feels the burden every day to live up to the gift he was given. He would have been dead within weeks without it. That's why he left coaching and now works as the outreach coordinator for the University of Wisconsin health system's organ procurement organization.

But it's one thing for the recipient to change his life because of his new organ. It's another for the donor family to measure the recipient's life in relation to that gift. "You become the judge. Were they worthy of receiving?" Liz Allison says. "That's not my place. I don't want to be that person."

There is no precedent for such a relationship. Would it ever get past its foundation? You're alive because my husband is dead. Your joy is made possible by my grief. "This crossed my mind many times: If I had met the recipients of Davey's organs, and maybe it wasn't a successful transplant," Liz says. "Or maybe they lived for a handful of years and then passed away. That's just another layer of grief and pain that perhaps one just doesn't need to lay on oneself."

*****

That's where this story would have ended as recently as late March. But then a few interesting things happened.

First, Liz Allison agreed to let Ellis of the Alabama Organ Center reveal to SI.com the ages and genders of the organ recipients -- none of which had ever been reported, details even Allison didn't know. Ellis pulled out Allison's file to find the information. It showed Davey Allison's heart went to a 54-year-old man, his liver to a 48-year-old woman, his left kidney to a 51-year-old man and his right kidney into a 46-year-old man. One of the kidneys went to California. The rest of the organs were transplanted in Alabama.

It's part of Ellis' normal duties to occasionally call recipients, and the pulling of the file prompted her to call the woman who received Davey Allison's liver.

She told Ellis she was interested in meeting the donor family. Ellis called Liz Allison and left her a message repeating the liver recipient's desire.

In the meantime, Liz Allison talked about the issue with the two children she and Davey had together. Her son, Robert, who was a two weeks short of his second birthday when Davey died, doesn't want to meet the recipients. Her daughter, Krista, is curious, albeit tentatively. After talking with Krista, Liz "warmed to the idea" of meeting the recipient, not because she changed her mind but because she was willing to do it to support her daughter.

Krista, 23, has some memories of her father -- she was 3 when he died. For years, she had dreams about that horrible day at the hospital, but they ended when she was 15. She says she always knew her dad's organs had been donated, but she had never thought much about it, until she and her mom started discussing it after they gave interviews to SI.com.

The idea of meeting someone who for 20 years has carried part of her father inside of her intrigues Krista Allison. But it worries her, too. "I just don't know exactly what they would want to talk about," she says. "I would love to meet them because the idea that's part of my dad is still living, I really like that idea. I just am a little cautious, I guess."

For now, that caution means no meeting is imminent. But Krista and Liz haven't ruled it out, either.

*****

While the liver recipient is still alive, the men who received Allison's heart and kidneys have died. Collectively, they lived 24 more years after their transplants. Shortly after Allison died, a newspaper published the name of a heart transplant recipient who received his new heart in UAB hospital on the same day Allison died there. The newspaper did not definitively tie the two together, and experts in organ donation caution against doing so.

The man's age appears to line up with the information released by the Alabama Organ Center, and members of the Allison family and the man's family believe he got Davey's heart. But none of them knows that for a fact. The only one who knows for a fact is Ellis, and privacy laws forbid her from saying without a consent from Allison and the man's wife.

Whoever's heart beat in his chest, the man had nearly five more years with his wife, three sons, two sisters, brother and grandchildren before he died while waiting for another heart transplant.

Saturday is the 20th anniversary of Davey Allison's death. He died in his home state of Alabama at Talladega Superspeedway. Allison's death shook a sport that was already reeling from other Allison tragedies. His brother, Clifford, had died 11 months earlier in a crash during practice at Michigan International Speedway. His father, Hall of Famer Bobby Allison, had been forced to retire in 1988 after suffering massive injuries in a crash.

Davey died in his prime. He won 19 races at the Sprint Cup level, including at least two in each of the six full seasons before he died. In NASCAR history, only 18 other drivers have won at least two races for six straight seasons, including Davey's father. Among current Sprint Cup drivers, only Jeff Gordon, Tony Stewart and Jimmie Johnson have done so, and only Johnson's streak is active. NASCAR analysts often say that if Davey Allison had not died, Dale Earnhardt would not have won seven championships and Gordon would not have won four.

Davey's death shattered many people -- Liz, Krista, Robert, Tommy, his sisters Bonnie and Carrie, his mom, Judy, and his father, Bobby. Because of the decision Liz and Tommy made together in that room in the hospital on that horrible day, Davey's death also saved four lives and enriched many others, including the recipients' family and friends and all the lives all of those people touched.

The impact of his donations goes even deeper than that, as Liz learned when she encountered Dr. Reddy. The coincidence of meeting a man who had seen her husband's heart get transplanted left her amazed. What he told her about the effect on his life took her breath away. Retelling it gives her chills.

Reddy told Liz that her husband's donation was a key point in his career. He entered medical school knowing he wanted to work on the heart but unsure in what capacity. Experiences like the one he had watching Davey Allison's heart transplant -- "you never forget your first," he says -- pushed him to become a transplant surgeon.

No matter how many heart transplants Reddy does, he still feels a sense of awe at that in-between moment, when he looks down at the chest in front of him, and there is a hole, where the old heart used to be, where the new one soon will be. He first saw that from afar with Allison's transplant. He has since seen it up close with dozens of patients. Allison touched all of those lives, too.