Danny Sullivan’s Indy 500 'spin and win' fame unlikely to be equaled

In season 2, episode 16 of Miami Vice, we find Crockett and Tubbs puzzling over the murder of a prostitute. They’d discover her body late at night, while in hot pursuit of a bone white Porsche 906 Carrera. The Porsche didn’t appear suspicious of anything more than having a bit of fun with the detectives—who, naturally, were trailing close behind in Crockett’s Ferrari Daytona Spyder—until the Porsche’s passenger side gullwing door whooshed open, and the girl’s lifeless body spilled out of the car and rolled onto the cold, dark street. Even though the detectives never caught up with the Porsche that night—Crockett spinning out in the throes of a 90-degree turn pretty much ended their race—the Porsche’s uniqueness, at least, gave the cops a better-than-fair shot of running down its mysterious driver.

A few scenes later, they had their chief suspect, the car’s owner, cornered inside an interrogation room back at headquarters. The man, a racing driver he’d call himself, was tall, blue-eyed and sandy haired. An innocent, he claimed in a quavering voice that betrayed a hint of a bluegrass accent. But his oily skin and 5 o’clock shadow suggested otherwise.

Even rougher than the man’s face was his alibi. His wife was two weeks overdue, yet he wasn’t with her in the hospital. He was out late drinking with racing friends ahead of the Miami GP, but those friends say the man parted company with them much earlier as it turns out. All right, all right, he tells the detectives. He wiled away the unaccounted for hours driving around Miami’s desolate streets in his truck, “listening to tapes.”

The higher Crockett and Tubbs turned up the heat, the more the man’s story fell apart. Funnily enough, those excuses weren’t the truly unbelievable part of this scene. It was the fact that the man making them was being played by none other than Danny Sullivan—not just an actual racing driver, but a damned good one. Thirty years ago, while leading Mario Andretti in the Indianapolis 500, he famously spun out and almost crashed, then didn’t, only to recover and pass Andretti again on the way to scoring if not the most dramatic triumph in Brickyard history, then maybe the only one with a clear, concise logline: “Spin and Win.”

The victory, as the 65-year-old Sullivan strains to point out, didn’t “separate me in any way from any of the other great champions” who have conquered the Brickyard. But it did make him, for a time, the glitziest of them all—a bona fide A-lister who, when not on the IndyCar circuit, was likely to be on a Michael Mann set running lines with Don Johnson (aka Crockett) and Philip Michael Thomas (aka Tubbs). “I was nervous as hell,” Sullivan recalls of his cameo and a scene that would go down as his most dialog-intensive. “I took acting lessons. I knew the script so well that I knew Don’s lines! I just wanted to make sure that I didn’t embarrass myself or my sport too much.”

That star turn on “Vice,” in 1986, was just one of many opportunities that Sullivan seized while crossing over from the insular world of racing into the American mainstream. He was a frequent guest on the morning and late-night talk shows. He appeared in a Spaghetti western with Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson, called “Outlaw Justice.” He emerged as one of the country’s most ubiquitous pitchmen, hawking everything from Ray-Bans to video games. He became an inspiration to a generation of racing drivers—not least, Jeff Gordon, who’d model his entire off-track career after the ’85 500 winner. Sullivan’s was a level of mega-celebrity that the Indy 500 still seems to promise. Yet no winner since has gone over as big. Why?

It was quite a big stage, and no star really filled it until Sullivan burst onto the scene in the early-80s with a story that was made-for-TV: He had grown up in Louisville, Ky., had worked a string of odd jobs (including one famous gig as a New York City cab driver), had cut his teeth in Europe while climbing the Formula 1 ladder, had addresses in Aspen and SoCal and counted the local glitterati among his neighbors and friends. Many of them turned up to watch him race—like Jill St. John, a Bond girl whom Sullivan dated for a time. And who could argue that their pairing didn’t, well, track? Slip a tux onto his trim 5' 11" frame and a martini glass into his hand, and Sullivan is a dead ringer for Roger Moore’s 007.

More to the point, Sullivan understood the important role that casting played in racing. To help promote that character, the jet setting racing driver, Sullivan enlisted the help of Alan Nierob, Hollywood publicist to the stars. Unlike the pairing with St. John, this association was a bit tougher for paddock insiders to process. “I took a lot of heat,” recalls Sullivan. “But I wasn't trying to see if I could get my name in the lights. Here’s what I learned in my fifth race ever: If I'm an equal driver to you name it—Bobby Rahal, Rick Mears, Michael Andretti, Emerson Fittipaldi, whoever—what’s going to set me apart that the sponsors are going to want to back me more than the other guys? That I’m more marketable than the next guy. That was the whole goal.”

This was essentially how Sullivan pitched himself to Nierob, who wasn’t exactly looking to add a racing driver to his client roster when the then-Benetton Tyrrell pilot strode into his office in 1983. “Somebody had talked to me about him,” recalls Nierob, “and I was like, ‘Eh. I’m not really sure. I remember they were racing in the Long Beach Grand Prix, at that time a Formula 1 race before it moved over to IndyCars. I just remember looking at the paper on Monday morning for his name to see where he finished. Eighth. Well .... that’s O.K. I guess I'll take the meeting. Literally, it was that matter of fact.

“I asked him, Why do you want to get business? Why do you want representation? I really had to understand if it was, I want to be an actor or something else in Hollywood. If that was it, I would’ve sent him packing—essentially, thanks but no thanks. But he said it in a way that he got it. And I’m like, Oh. O.K. That, I can do. I can make a brand more favorable or more positive or increase brand exposure to increase awareness and, hopefully, attract sponsors. I actually know how to do that really well. So I said, you got it. Let’s do this.”

[pagebreak]

Sullivan’s PR machine operated on three simple gears. First, they had to make him matter to the folks back in Kentucky. (“You start with the cover of Louisville Magazine,” Nierob says.) Second, they had to make him compelling to sports writers. (This 1984 profile by SI’s Bob Ottum shows just how great and abundant a provider of material Sullivan could be.)

Third, and perhaps most importantly, they had to make Sullivan intriguing to non-racing fans. Landing real estate in general interest publications became a priority. “So he does the fashion layouts in Vogue Hommes, in Italian Vogue,” Nierob says. “He does a GQ thing. Most of his peers didn’t see the value in that. But we knew we wanted to build a portfolio so when it came time and he delivered the goods, he was positioned properly.”

That day finally came at Indianapolis Motor Speedway on May 26, 1985. Sullivan was running his second ever race for team owner Roger Penske—who, back then, could only call himself a three-time 500 winner (albeit thanks to the heroics of Mark Donahue in 1972, Rick Mears in ’79 and Al Unser in ’81). Moreover, Sullivan’s first two cracks at the Brickyard’s 2-1/2 miler had ended with a pair of accidents.

Sullivan qualified eighth—better than his last two qualifying runs (13th and 28th), but not as good as the last 10 Indy 500 winners, who had started no lower than the fifth position. At green flag, he set off with a car that was strong but slightly out of balance. To correct the issue, his chief strategist, Penske team manager Derrick Walker, brought Sullivan into the pits during the third quarter of the race, out of sequence with his competitors.

The logic was that an outright faster car (or one that would be once properly balanced) could beat another with fresher tires and more fuel. Sure enough, upon exiting the pits, Sullivan ran down race leader Mario Andretti. Rather than ride in Andretti’s slipstream and conserve fuel, an excited Sullivan, unable to hear radio orders to hang back, attempted an inside pass on Andretti going into Turn 1. Sullivan got by, but not before Andretti squeezed him down to the apron.

What happened next is the stuff of racing lore: Sullivan’s inside rear wheel slips on the boundary between the apron and the track, sending him spiraling counterclockwise toward the wall in a plume of smoke. “I was like, Dammit… I had just gotten in the lead of the Indy 500. Now I’m gonna hit the wall. I was so frustrated.”

But a funny thing happened on the way to that wall, Sullivan never hit it. Nor did he collide with Andretti, who was trailing close behind. “I was lucky as hell to miss him,” Andretti says. “I could’ve just dinged him just a little bit. Or he could’ve just nudged the wall with the wing.”

When the smoke cleared, Sullivan was pointed “toward the Turn 2 suites,” he says, in the right gear (after taking a beat to choose carefully) and rolling ahead of onrushing traffic. What’s more, Sullivan’s near miss brought out the yellow flag, putting him back into a pit sequence with the rest of the field—Andretti, most important of all.

From there, Walker’s strategy won out. “Danny had a faster car,” Andretti says. “That was everything.”

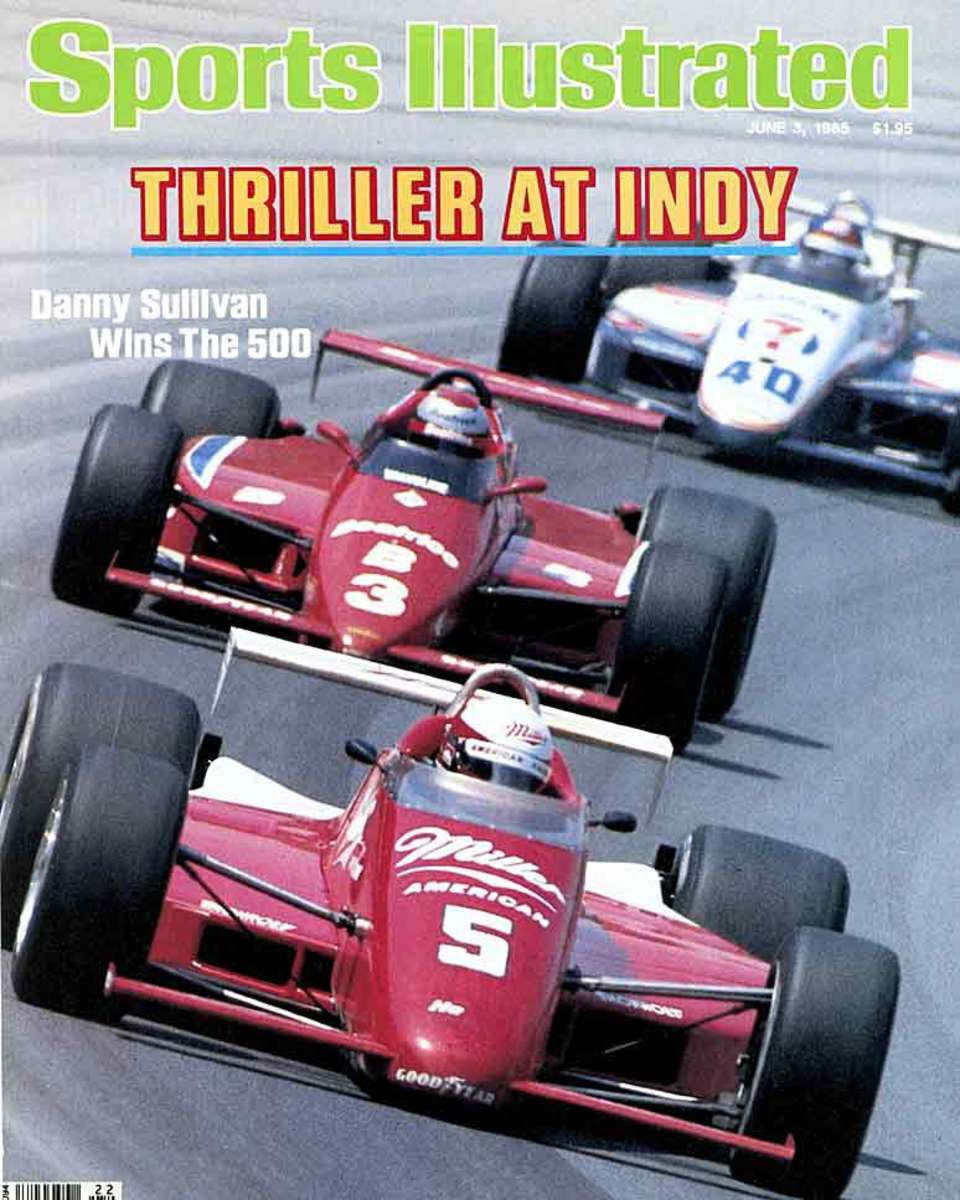

Once Sullivan ran down Andretti again and passed him—“in the same spot,” Sullivan notes—and skirted another seemingly certain disaster, a collision between Howdy Holmes and Tom Sneva, Sullivan brought the No. 3 Penske car home in first place. Then he hopped out of that machine and into the hype machine.

“You know,” says Nierob, “there was a great piece in that race that we had ABC Sports produce on Danny, and it was really about [the jet setting racer character]. But when he won the race, that really became who he was. A lot of people [tuning into the race] didn’t know him. But when they saw that piece before he won the race, they went, ‘Oh, this guy is interesting…’

“But then he wins? Former New York cabbie? Former New York cabbie was the key. Hollywood, Middle America, Madison Avenue—they all owned him. They all thought, He’s ours. He's one of us. Our guy won the race. Now you do that and you’re everywhere else and in New York? Come on. That's easy. That’s even fun.”

The following week Sullivan’s media blitz was in full swing, starting with appearances on all three network morning shows and SI’s cover.

After the Spin and Win, Sullivan was confident that hype around the 500 winner would only get bigger. But that hasn’t happened for a variety of reasons. The sports marketplace has never been more crowded. The networks are tougher to get on. In fact, this weekend’s IndyCar doubleheader at Belle Isle raceway will mark the series’ final appearance this season on ABC.

Furthermore, open-wheel racing’s mid-90s spit up—into IRL and CART—created an opening in the marketplace, and NASCAR quickly pounced. “IndyCar was enjoying the best moments in the ’90s before [Indianapolis Motor Speedway president] Tony George decided to go his own way and create this confusion that the fans just rebelled against,” says Andretti. “And NASCAR just picked it up and immediately went mainstream. They should thank him. I hope they have him on their Christmas card list because he gave them Indianapolis.

“By Tony George giving NASCAR Indianapolis [for the last decade, the track has hosted Sprint Cup’s Brickyard 400], he gave NASCAR the biggest stronghold to mainstream. And Tony never knew the damage that he did to his own side of it. The damage that he did—and I’ll say it; I’m sorry, Tony—but it’s incalculable.

“IndyCar today is strong in a way of talents. The racing is as good as ever. Better than ever. But somehow not enough people or the press pay enough attention. The great drivers that don’t get their due.”

Still, that’s not to say they don’t go through some of the motions. After his thrilling victory at the Brickyard last Sunday, Juan Pablo Montoya has shuffled from one publicity stop to the next—but mostly at places like Fox Sports Business and CNBC. His Tuesday appearance on Good Morning Americaelapsed a mere 90 seconds, or less than a minute longer than it takes him to lap the speedway at some 226 miles per hour. Overall, Montoya’s victory lap barely lasted two days. There doesn’t figure to be a cameo on Modern Family in Montoya’s future, even with the ABC tie-in and a self-crafted character sketch (on social media, as a goofy father of three) that would make him easy to cast opposite Sofia Vergara as, say, a long lost cousin of Gloria Pritchett’s.

By comparison, Sullivan, now happily married for almost two decades and operating his own business in the aviation sector, was such a frequent presence on GMA that host Joan Lunden considered him as part of the cast. He remains such an enduring figure in the Zeitgeist that autograph seekers still approach him. Some know him from his epic save. Some know him from … from … from somewhere—at which point he gently tells them to “Google spin and win.” The rest?

“They’re like, ‘We saw you on Miami Vice,’” he says.

Clearly, that autograph is definitely worth something. Danny Sullivan was an American open-wheel racing superstar. We may never see the likes of him—off the track, at least—ever again.

Does Indy 500 winner Juan Pablo Montoya see himself as the villain?