Original report: Ray Harroun wins first Indianapolis 500 in 1911

Few knew what to expect when they converged on Pressley Farm that May morning, not even the reporters who arrived at the sprawling banked oval for the first International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race.

Now, 105 years later, The Associated Press is making its original Indy 500 report available.

Using antiquated verbiage - words such as ''whirligig'' that have long left the lexicon - the dispatch from the ''the great 500-mile speed battle'' has itself become a part of the race's rich history.

The meandering narrative, written in the linear style of the time, describes fierce battles among drivers and the first death associated with the famous race. It highlights the modern technology of the cars, the fearless drivers who piloted them and effectively lifts the curtain on ''The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.''

(Associated Press Night Report.)

INDIANAPOLIS SPEEDWAY, May 30 - Eighty-five thousand spectators saw forty of the fastest motor cars on earth started at 10 o'clock this morning in the great 500-mile speed battle in which one man lost his life and three others were seriously injured.

Johnny Aitkin, in the National, jumped into the lead at the end of the first mile but withdrew after fighting for 325 miles of the contest.

David Bruce Brown in the Fiat held the lead at the end of 100 miles, but his time was well behind the record of Teddy Tetzlaff, which is 1h. 14m. 29s. Spencer Wishart, in the Mercedes, was pushing Brown hard at the end of 125 miles but the Fiat driver held his place. Tire trouble hindered the Mercedes, and Brown continued to gain, only to lose his place later in the race to Harroun, in the Marmon, and Mulford, in the Lozier.

In the first lap the cars strung out all around the course. Aitken, in the National, held the lead, with De Palma in the Simplex second, and Wishart, in the Mercedes, third.

The leaders, pressing the tail-enders of the preceding lap, made the race right at its beginning an enormous and desperate whirligig. The thousands of spectators leaned forward in their seats and yelled wildly as their favorites passed. The great bowl of the speedway was filled with the deafening roar of the explosions of the forty motors as the hooded drivers, bending low over their steering wheels, pushed their engines to the farthest.

At the end of the first 150 miles of the 500-mile automobile race at (word illegible) today, one mechanician had been killed and a driver perhaps fatally injured. Four of the forty cars that started had been withdrawn because of breakdowns. David Bruce-Brown, driving a Fiat, was leading a long grind that promised to continue until 5:30 o'clock this afternoon.

S.P. Dickson, mechanician for Arthur Greiner of Chicago, driving an Amplex car, lost his life in an upset on the back stretch in the thirteenth mile of the race. Greiner suffered several broken ribs and perhaps concussion of the brain. Surgeons at the field hospital would not make a statement as to the probable outcome of his injuries.

The accident was caused by the throwing of a front tire. The machine skidded to the infield and whirled completely around, tearing off both back wheels. Dickson was thrown against a fence. His body was terribly mangled. Greiner was hurled to the track. An examination at the field hospital, and a report made by the attending physicians, gives Greiner more than a fair chance to recover.

Bruce-Brown's time for the 150 miles was 1h. 59m. 12s., which is a new record, the old mark being 2h 1m. (detail illegible) by Joe Dawson of Atlanta last year. The cars were strung out behind the leaders all around the two and one-half mile course. The scorching pace burned up the tires and most of the cars had stopped one or more times at the pits for changes.

Several of the drivers apparently preferred to keep up a steady grind two or three laps behind the leaders. There were few sensational brushes for leadership.

GALLERY: Looking back at the evolution of the Indy 500

Looking Back at the Evolution of the Indy 500

1911

The lineup for Indy's first 500-mile race was led by a convertible pace car (lower right). The photographer? Yes—it's Mr. Henry Ford.

1913 - Where there's a Will...

Billy Knipper (10) passed Billy Liesaw (17) and Bill Endicott (33) as they pulled over to pit. Liesaw, though, wound up the fastest of the Billys, finishing 14th.

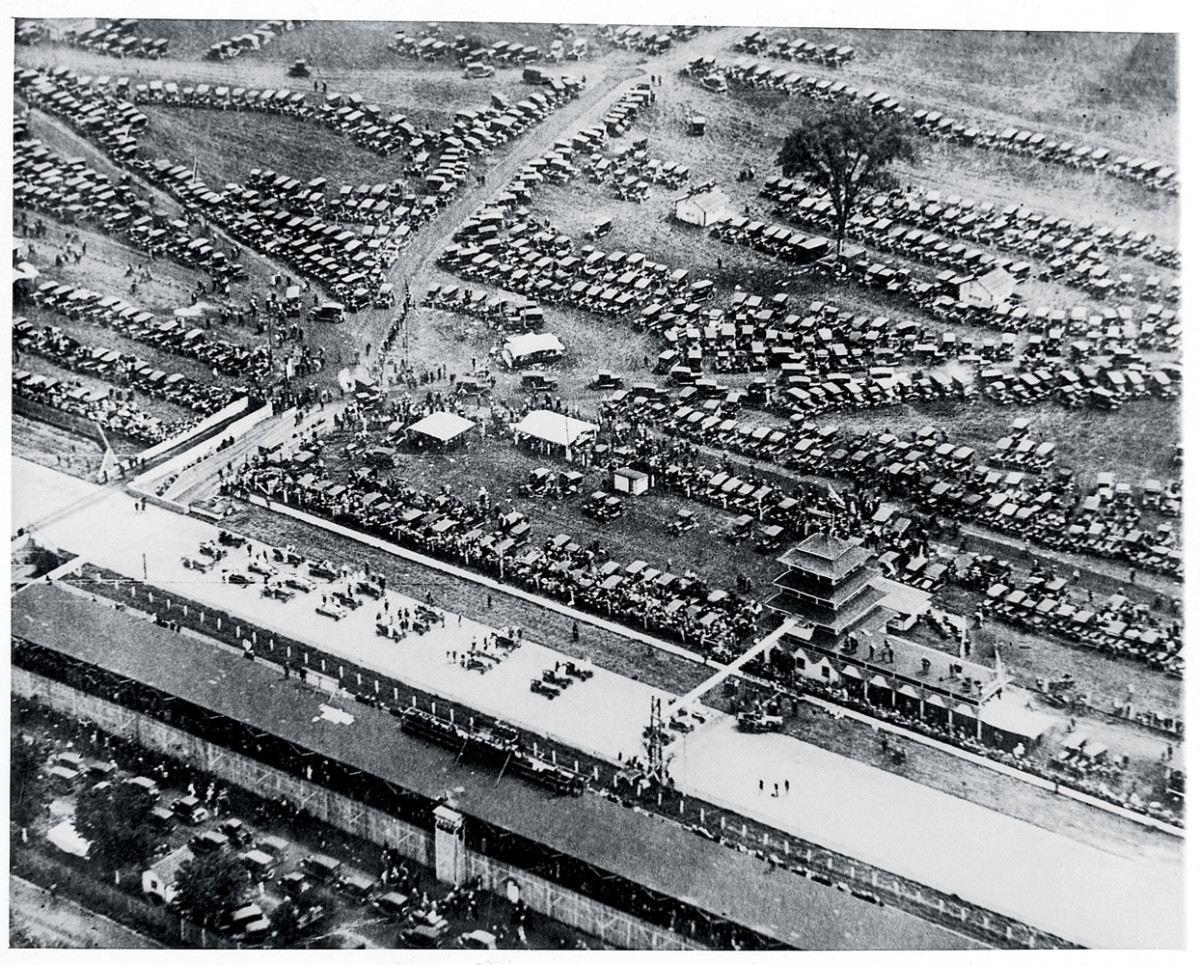

1923 - Calm Before the Vroom

Fans were still milling around their own cars in the infield as pole sitter Tommy Milton led the field past the starting line.

1926 - Circling the Bricks

The track isn't the only place to find cars during a race: In the Roaring '20s fans parked their Model T's in the infield. Back then the racing surface exposed a while lot more than a yard of bricks-repaving in asphalt was still a decade away, as was swigging dairy for champs. Rookie Louis Meyer, who would later start the ritual when he became the 500's first three-time winner, was a milkless victor in '28.

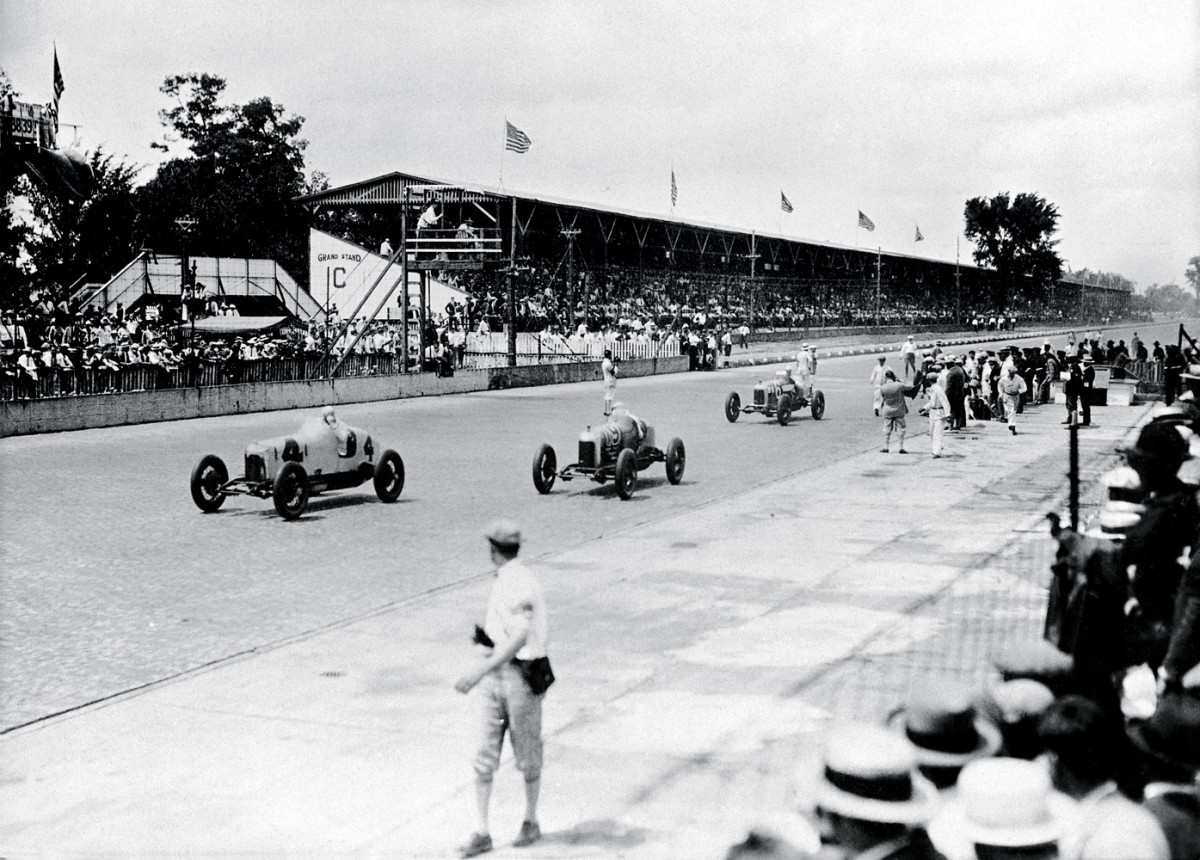

1931

The "paddock" overlooked this straightaway, and in a messy race Billy Arnold broke an axle, Wilbur Shaw went over a wall and Louis Schneider won.

1938 - The Checkers Stand Alone

With no traffic to challenge Floyd Roberts at the finish, the started signaled his victory while moving safely toward the middle of the track.

1948

Crowds came out in full force (as well as in full headgear) and saw Mauri Rose win his third, and last, 500. Rose's car is far left at the starting line.

1949

Norm Houser took an infield detour to dodge the trail of fire left by Duke Nalon's crash into the retaining wall. Nalon's injuries knocked him out of racing for two years.

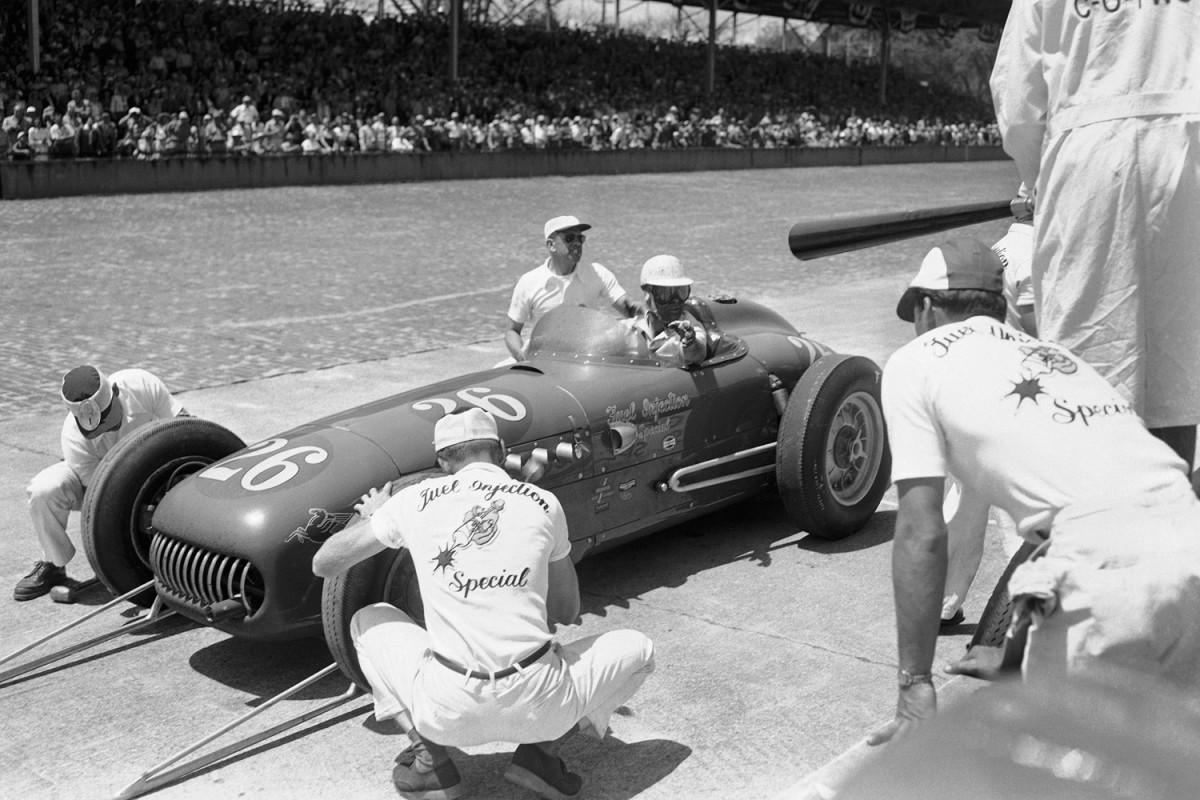

1952-59 - It's What's Inside That Counts

The chassis were different, but the engines remained the same. Troy Ruttman and Rodger Ward pitted a 1952 Kuzma and a '59 Watson, respectively, to tune up their Offys, while Sam Hanks, behind the wheel of a Salih in '57, safely revved his around a retaining all. Another thing they all had in common: They won their races.

1957

Despite the high casualty rate on the track crowds continued to turn out, enthralled by the ever-increasing speeds of roadsters roaring round the bend.

1964 - Times Are A-Changin'

Black clouds of gloom hung over the Speedway after the deadly '64 crash, the first time the Indy 500 was halted for an accident. The second was two years later, when no one died, but rookie Jackie Stewart endured heartbreak; he led 40 laps before late mechanical failure ended his title hopes.

1969

Although he was flanked by past winners Bobby Unser and A.J. Foyt (6) at the start of the race, Mario Andretti prevailed to take his first and only checkered flag.

1973 - A Career Cut Short

Swede Savage was already a darling at Indy, a sunny 26-year-old out of California with loads of speed. He had driven his Eagle-Offenhauser to a qualifying record of 196.580 mph when these photographers descended. Two weeks later, in the 500, Savage was battling for the lead and carry a full tank of gas when he crashed into the inside wall and was thrown, engulfed in flame, across the track. He died 33 days later.

1975

Not to be outdone by Al's two titles, Bobby nabbed his splashy second victory after he was leading on the 174th lap and the race was declared over on account of rain.

1984

Starting from the third position, Mears (6) led the field fro 119 of the 200 laps, his only Indy victory that did not start from the pole. He won a record six poles at Indy.

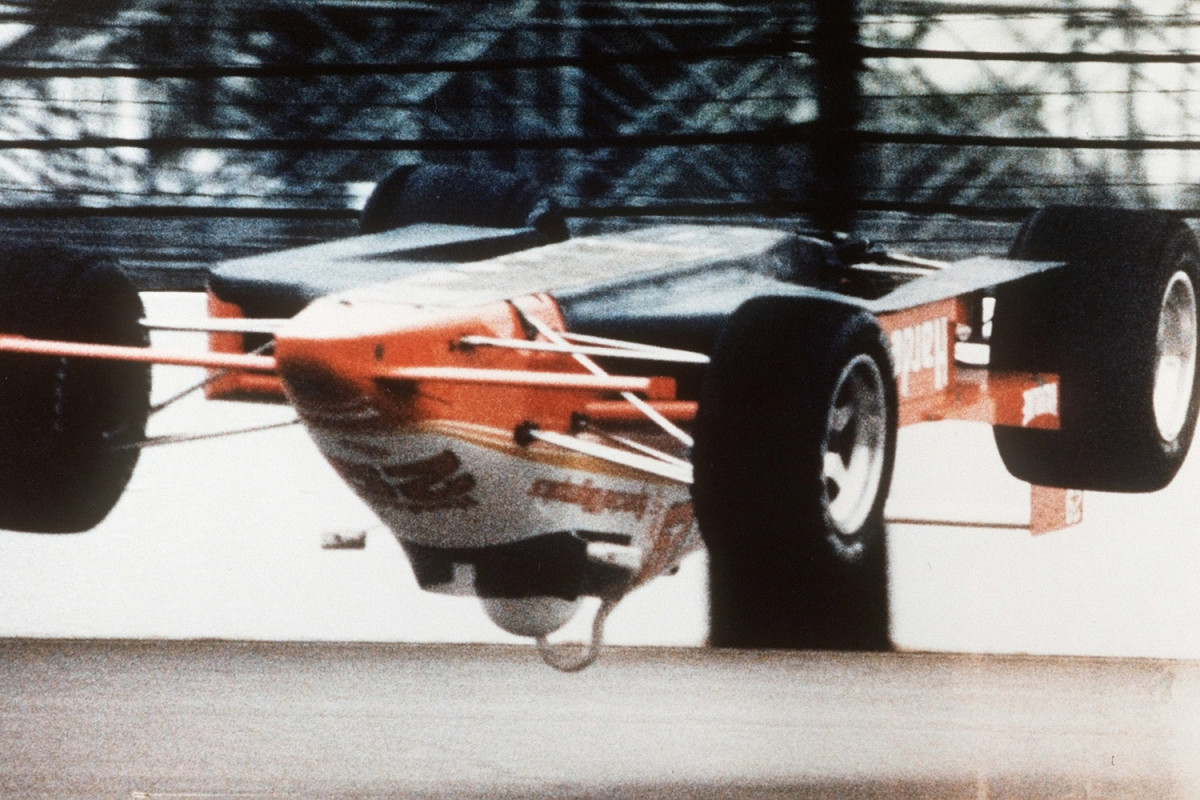

1987

Pancho Carter flipped head over tailpipe in practice, sliding on his head for more than 800 feet. Uninjured, he raced (with a new helmet) three weeks later, finishing 27th.

1996 - A Time of Turbulence

Boycotted by many drivers, the first postsplit 500 retained some golden rules-slow down to avoid debris and don't follow the rubber to the wall.

1998 - A Feeling in the Air

The annual tradition of getting the 500 underway by releasing some 30,000 helium-filled balloons (just as the last note of Back Home Again in Indiana is sung) presaged a paradoxical race. It was once full of no-names (many top drivers were in CART) and incomparably rich. The biggest chunk of the record $8.7 million purse went to winner Eddie Cheever Jr., who came from the 17th position for his only 500 victory.

2001 - What a (Bas-) Relief

When Helio Castroneves became the eighth rookie to win the 500, his smiling mug was immortalized in sterling silver alongside every winner since 1936. The 75-year-old Borg-Warner Trophy weighs around 110 pounds and stands about 5' 5", so it's no small thing to hoist. It's also valued at $1.5 million, a nice sum but not as valuable as winning the Indy 500: That, as any driver would say, is priceless.

2005

Dan Wheldon, shown here, won the Indy 500 in 2005, marking the first time an Englishman won the storied race since Graham Hill's victory in 1966. In 2011, Wheldon tragically lost his life in a 15-car accident at the IZOD IndyCar World Championship at Las Vegas Motor Speedway.

After the two hundredth mile several of the pilots dropped out to rest a few minutes and relief drivers took their places in the cars. Patsche drove the Marmon ''Wasp'' for Harroun for several laps, and Lindenstruth substituted for Hearne in a Benz.

In a mix-up of Lyttle Apperson, Knight's, Westcott and Jagersburger's Case, directly in front of the grand stand, John Glover, Knight's mechanician, suffered an injury to the spine. The others escaped anything more than bruises by a wonderfully fortunate set of circumstances.

The Case car broke its steering gear and skidded to one side of the track. Larroneur, the mechanician, fell out and the car passed over his leg. The cars behind made desperate efforts to escape a collision and all of them swerved by safely except the Westcott and the Apperson, which turned over.

Eleven cars had withdrawn because of accidents and breakdowns within the two hundred and fiftieth mile was reached. Thus left a field of twenty-nine cars to finish the last half of the races. The entries withdrawn up to this point were: Louis Disbrow, Pope-Hartford; Harry Knight, Westcott; Joe Jagersburger, Case; Arthur Chevrolet, Buick; Charles Basle, Buick; Harry Grant, Alco, Ellis, Jackson; Teddy Tetzlaff, Lozier; Herb Lyttle, Apperson; Caleb Bragg, Fiat; Arthur Greiner, Amplex.

Ray Harroun (Marmon) had taken the lead from David Bruce-Brown at the 200-mile mark. Harroun's time for that distance was 3hrs, 43m., 21s. Brown was second and Ralph Mulford (Lozier) was third.

At 300 miles Ray Harroun continued to lead. His time was 4hrs, 3m, 24s. Ralph Mulford, in the Lozier, was second, and Bruce-Brown, in the Fiat, third.

Ray Harroun, in his Marmon, had a lead of about three laps at 350 miles. His time was 4 hrs, 44m. 14s. Ralph Mulford, Lozier, second; Joe Dawson, Marmon, third. Twenty-eight of the original starters continued in the race at this time.

At 400 miles Harroun, in the Marmon, was well in the lead. His time for that distance was 5hrs. 22m. 15s. Ralph Mulford, in the Lozier, was second, and Bruce-Brown, with the Fiat, third. Twenty-seven cars remained to drive the last 100 miles of the race.

The average time made by Harroun in his Marmon for the first 400 miles was seventy-seven miles an hour.

As the cars dashed into the last 100 miles of the race it appeared that the drivers, instead of weakening from fatigue, and the nervous strain, gained assurance. They took more chances in attempting to lead each other at the turns and the crowd, excited by the mishaps and the hairbreadth escapes of the day, watched the cars eagerly as they turned in and out of the home stretch and the back stretch.

At 470 miles, Harroun, Marmon, led, Bruce-Brown, Fiat, second, Mulford, Lozier, third, Dawson, Marmon, fourth, and De Palma, Simplex, fifth.

At 480 miles the three leading cars were less than thirty seconds apart.

Mulford, in the Lozier, raced ahead of Bruce-Bowen, in the Fiat, for second, at 480 miles. Harroun, Marmon, in the lead, was being crowded by Mulford; time, 6hrs. 25m.

The thousands of spectators in the stands rose to their feet as the three leaders in the race entered the final 20 miles. Harroun (Marmon) was leading with Bruce-Brown only half a mile behind, and Mulford (Lozier) trailing Bruce-Brown about the same distance. Bruce-Brown gained on Harroun and it was apparent that the finish would be very close.

The Marmon ''Wasp'' made only four stops during the entire run, each time to change tires on a rear wheel. Each time oil and gasoline tanks were filled to prevent stopping for fuel.

After one of the early stops Patsche relieved Harroun at the wheel for a short time.

Harroun was born at Spartansburg, Wis., and is 29 years old. He holds a long list of records and has won many trophies. Harroun won more firsts than any other driver during 1910. He retired from the racing game at the close of the season but was induced to compete in this 500-mile event.

He has won among other trophies the 200-mile trophy, the Atlanta speedway trophy, Atlanta Automobile Association trophy, and the two hour's race for all trophies of the Los Angeles Motodrome.

As Harroun drove up to the Marmon pit he was surrounded by a wildly enthusiastic crowd. He ran his car into the infield and stopped.

''Gee, I'm hungry,'' he said, as he crawled out from under the steering wheel.

Asked to make a formal statement the victor in the first 500-mile event ever run on a speedway said: ''All credit is due my car for the victory. At no time was the throttle wide open and I relied wholly on consistent high speed to win for me over occasional bursts in the back stretch. The weather was noticeably warm, although I did not suffer in any way from the heat.

''The last hundred miles was by far the easiest of the entire run and the car was less difficult to handle on the turns. At first there was a tendency to slip, which increased toward the 200-mile mark but from that time I had little trouble in holding the car to its course.

''In my estimation the limit is reached at 500 miles and is entirely too long for the endurance of the driver.''