Lady Leadfoot

This article was published in partnership with Epic Magazine.

March 20, 1961

Sebring, Fla.

Five days before the race, the automobiles began to appear in this small backwater town. They came on trailers, on huge haul-aways, on tow-bars behind passenger cars and some under their own power, all accompanied by crews of eager, purposeful men and a few purposeful women. Their goal: to compete in (or at least witness) the Twelve Hours at Sebring, one the premier sports car events in the world. The race’s formal name was the Sebring 12-Hour Grand Prix of Endurance, and the need to endure affected everyone, not just the drivers. Pity the local resident who had the misfortune of blowing an engine during the run-up to the start, because garage space—even filling station space—was suddenly unavailable. Noisy strangers—weekend hobbyist racers and top-flight factory teams alike, including the finest drivers from both the old and new world—thronged restaurants in the center of town. Tourists passing through on their way north were well advised to take alternate routes, for every available bed, even empty bunks in the local jail, had been booked for months.

That said, no one visited Sebring to sleep. In the run-up to race day, the pungent punch of orange blossoms that normally filled the air was replaced by the sharp smell of burned castor oil and exhaust. Even in the small hours of the morning came the sound of engines revving and growling and howling. Over several days of hard-won practice, it would become clear that this Sebring Grand Prix would be a faster and tougher than ever before. One driver completed a one-lap practice dash of the 5.2-mile, 12-turn course in just three minutes and twelve seconds—a record! And every evening after practice sessions ended, the lights in the garages burned for hours as drivers and their crews sought to identify and switch out their cars’ weakest components, hoping for victory.

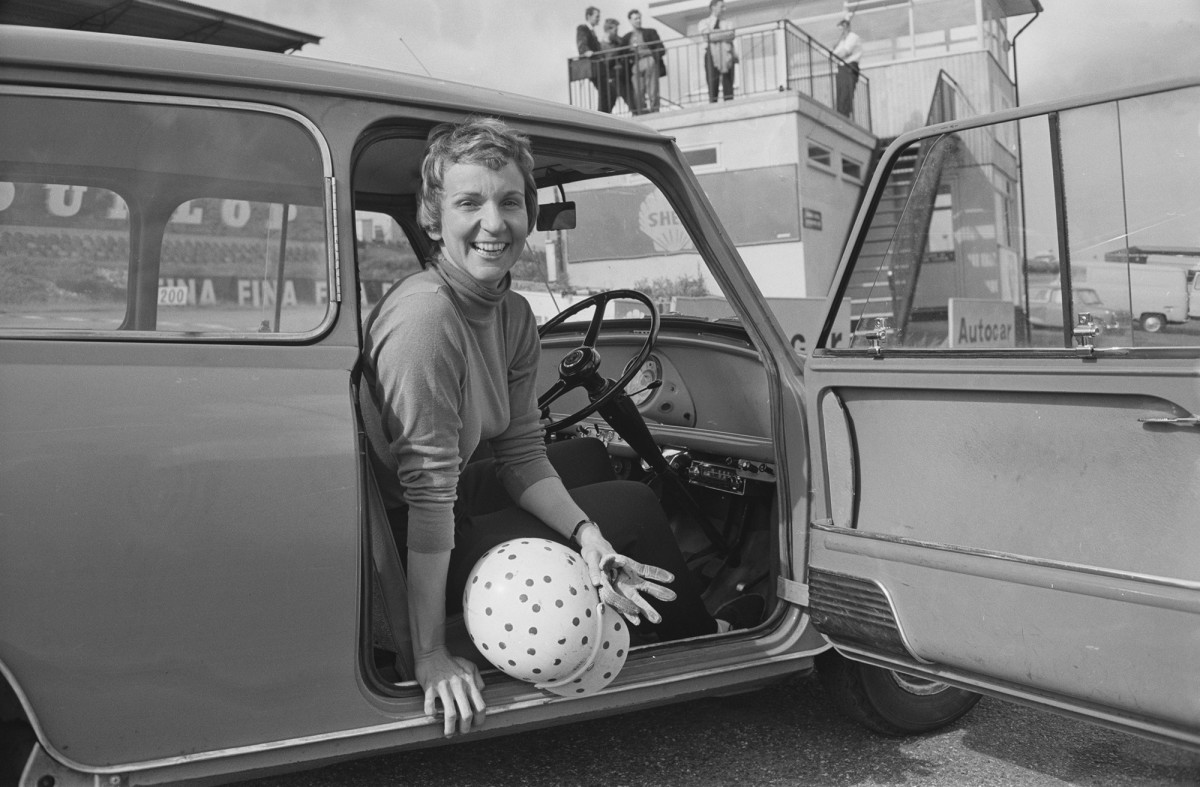

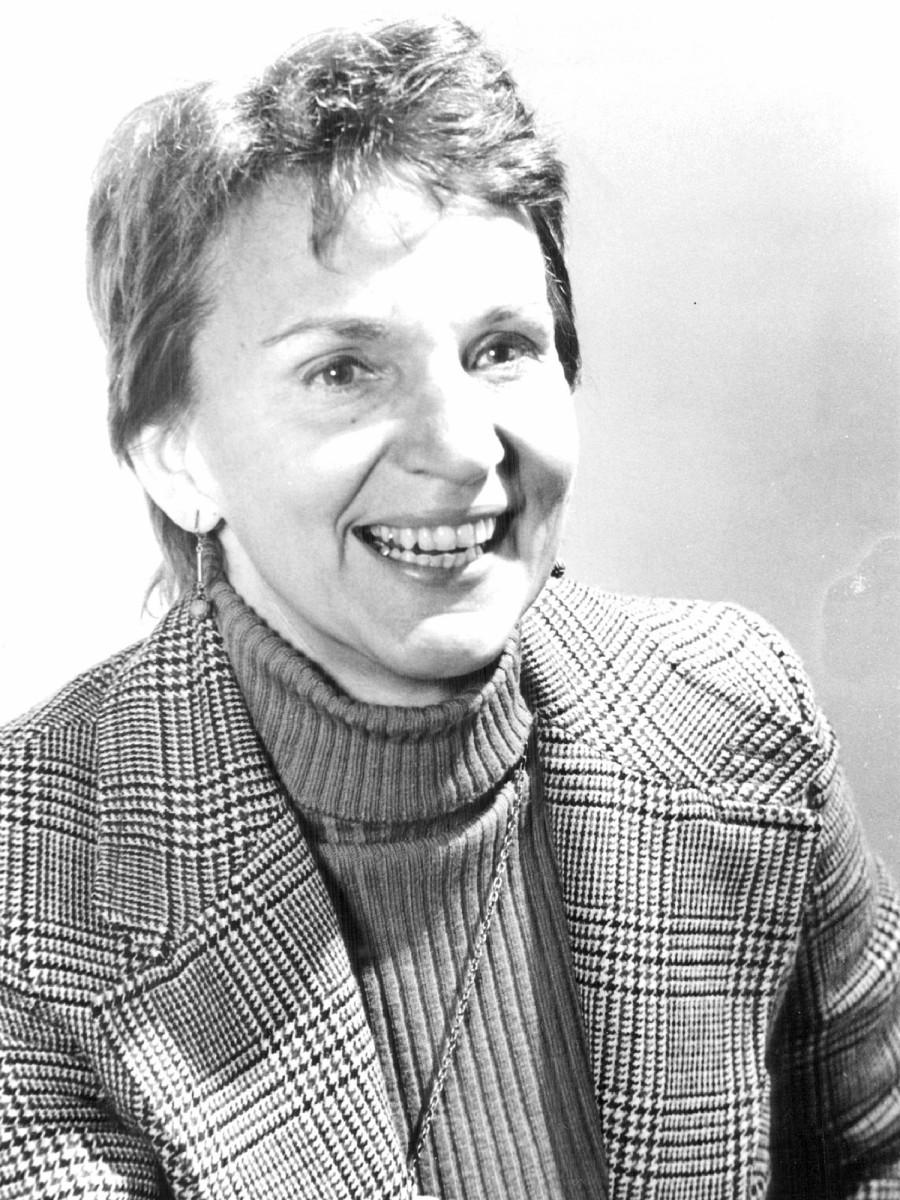

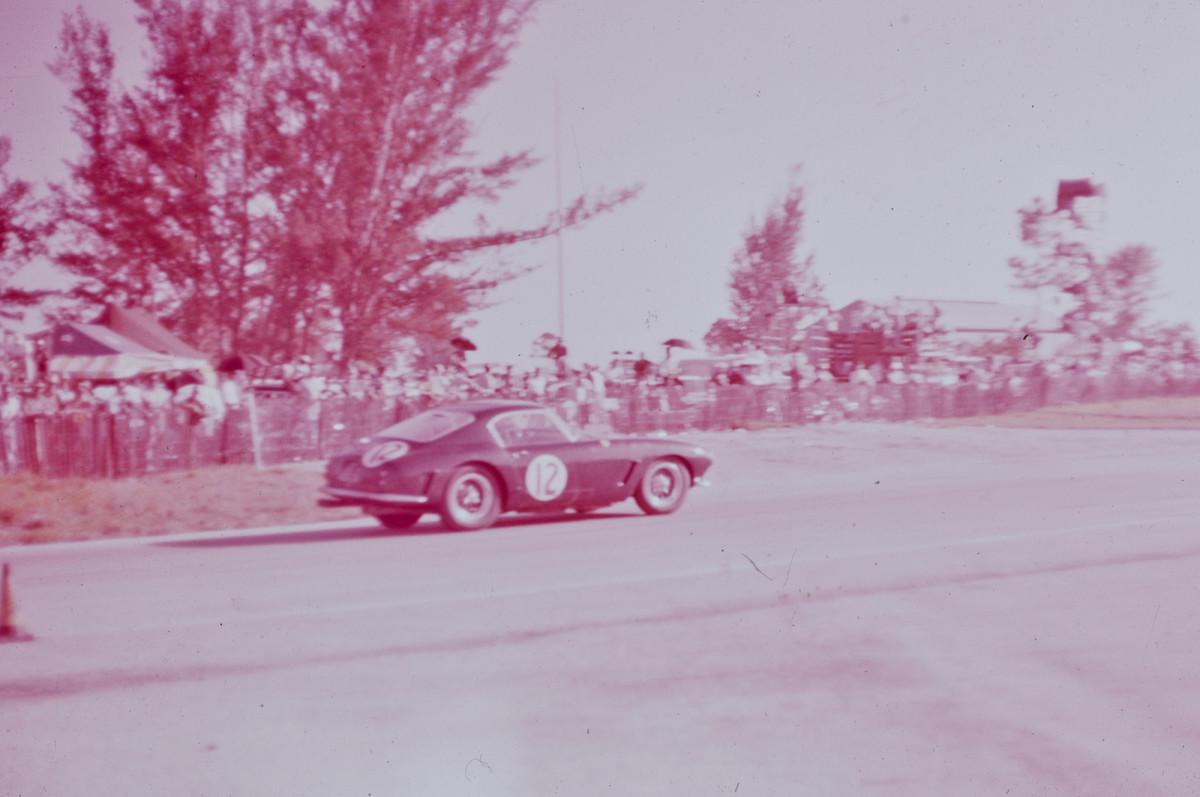

Into this happy chaos drove Denise McCluggage, a 34-year-old amateur racer who had just bought her very first Ferrari—a dark blue “mouthful of a car,” she liked to say, “with superb handling and wonderful manners.” The used 1960 250 short wheel-base Scaglietti-bodied Berlinetta had set her back $9,000 and was the most expensive thing she’d ever owned by a factor of three, but McCluggage had no doubt it was worth it. A lean, 5-foot-6-inch beauty with short-cropped hair and angular features, she’d been a sports car freak since the age of six. Now, as European sports car racing really began to catch on in the United States, she’d earned a nickname: Lady Leadfoot.

McCluggage’s entrée to the sport was unusual: She was a journalist who had a reputation for participating in and excelling at the extreme sports she covered. She had jumped out of airplanes, skied treacherous mountains, become a champion fencer—all in search of what she called “the perfect meditation” that well-honed exertion can bring. No matter the contest, she always played to win. But she’d lost at Sebring before—three times. In 1958, she’d raced in a borrowed Fiat-Abarth 750 Zagato but didn’t finish. In 1959, her team came in 18th in an OSCA. In 1960, she drove in another OSCA, but didn’t complete the race. Now, on her fourth consecutive try, she hoped driving her own Ferrari would give her an advantage. In terms of international prestige, Sebring was second only to the 24 Hours of Le Mans, in France. But the French didn’t let women drive. This, then, was McCluggage’s shot at the big time, her chance to go down in history. Maybe this race would bring her better luck.

The only question was with whom she would share the driving. No one completed Sebring’s dozen hours alone. The course demanded not just concentration, but agility and physical strength. It was utterly exhausting, which is why several cars would be piloted by as many as four people. This year, McCluggage planned to make do with two. If she had her way, she and her boyfriend—a jazz saxophonist named Allen Eager—would take turns in the Berlinetta, spelling each other, switching out when it was time to refuel. McCluggage had been coaching Eager for months; this would be his first race ever. But to qualify, he had to pass the physical. And that was by no means a sure thing.

The first time Denise McCluggage cracked a joke, it was about a car. She was five years old, riding in a Dodge sedan her father was thinking of buying. The salesman was taking her family for a demo ride, and was weaving sharply in and out of traffic. “No wonder they call it a Dodge,” she piped up from the back seat, and everyone laughed.

That Dodge notwithstanding, the McCluggages were an Oldsmobile family. They had a mud-colored sedan, probably a ’36. Each summer, it transported the whole clan—Robert, a lawyer, Velma Faye, a court reporter, Denise and her two younger sisters (a third had died of measles and pneumonia)—from Topeka, Kansas, to Tincup, Colorado, to escape the heat. Every year, upon arrival, they would take up residence in a rented log cabin chosen for its location (next to a creek, famous for good fishing) more than its amenities (no plumbing and no electricity).

One summer, the family went to watch the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb—an annual race run on the narrow dirt roads that ascend the mountain’s face. It was there that she first saw Louis Unser, whose nephews Al and Bobby would later combine to win seven Indy 500s between them, and even filmed him with the family’s eight millimeter camera. Years later, he would pilot a Maserati to victory on that course. For the rest of her life, Denise would call the daring, dark-haired Unser her hero.

Cars always seemed to speak to her. There was the Baby Austin 7 she saw when she was six, parked on the street in Topeka. (She promptly asked Santa to bring her one for Christmas). There were the kiddie-sized racers her family encountered at a carnival in Manitou Springs, Colo. Denise got to drive one for a dime a lap, and put her foot down, hard.

March 25, 1961

Sebring, Fla., 9 a.m.

With one hour to go before the start, there was no avoiding the jitters. After months of preparation, the Sebring four-wheeled endurance marathon was about to begin.

Denise McCluggage was ready; she even had a back-up plan. Worried that Allen Eager wouldn’t be allowed to compete, she’d invited another driver, Fred K. Gamble, a Floridian who’d raced a Corvette the previous year at Sebring, to join her team as an alternate. The reason: Like many jazz musicians, Eager had experimented with drugs. Heroin, specifically. Though he’d been clean for some time, McCluggage worried the mandatory physical might trip him up. Moreover, Gamble recalled: “We didn’t think the race organizers would let him drive, because he’d never driven a race before.” But McCluggage and Gamble hadn’t factored in Eager’s star power. The saxophonist had played with Tommy Dorsey! He knew Miles Davis! The race organizers loved the buzz Eager’s fledgling race would generate, so they cleared him to drive. Gamble, relegated to the sidelines, would shoot home movies of the race.

Now, it seemed as though all the energy in town converged around the track. After just 10 years in existence, the Sebring International Raceway had a well-earned reputation as a treacherous course. Like many early racetracks, on series of a World War II era landing strips—the former Hendricks Army Airfield. The concrete expanse was broken by large seams, its surface so uneven that racers often scraped their cars’ undercarriages as they careened by, sending sparks flying. Even the best drivers had trouble keeping a grip on the wheel. Then there was the track’s irregular shape. Instead of an oval, Sebring was a road course whose dozens turns included one head-spinning hairpin and several high-speed 90-degree corners. There was very little elevation change and little camber—or tilt—at the turns, which made it difficult to maintain speed while turning. As if that weren’t enough, the course was poorly marked with orange cones banded in reflective tape. Since the race began precisely at 10 o’clock in the morning and ended at 10 o’clock at night, drivers would be navigating these obstacles for about four hours in the dark—a confusing task at best and, at worst, a fatal one.

McCluggage knew the risks were real. She’d seen more than one racing phenom lose his life to the sport—Herbert MacKay-Fraser, Jean Behra, and Peter Collins to name a few. This was a time before roll bars and flame retardant suits, an era when race car driving was defined largely by machismo. Few women attempted to compete in such a male-dominated space; those who did were mostly relegated to so-called Ladies Races or “Powder Puff Derbies.” But today would be different. Of the 65 vehicles entered, two would be piloted by teams that included a woman driver.

In endurance sports car racing, the cars are the stars. Most fans root for manufacturers, not drivers. This year, the cars were as varied as they were spectacular. Two Triumphs, three Arnolt Bristols, four Sunbeam Alpines, five Corvettes, six Maseratis, seven Porsches and 13 Ferraris were competing, not to mention a few OSCAs, Alfa Romeos and Elva Couriers, among other models. As always, there were two categories for the entrants—Sports Prototype and Gran Turismo (or GT). As a general rule, GT cars are vehicles you could buy at a dealership that have been prepared for racing, while Prototypes are limited production cars built specifically for racing. At the end of 12 hours, one car would win in each category. All told, the 65 cars would be driven in shifts by 145 drivers.

With its engine running, McCluggage’s Ferrari would be blazing inside—way hotter than Florida’s balmy 75 degrees. But she didn’t care. She strapped on her signature polka-dot crash helmet, determined to win.

Denise McCluggage would never forget the sight of her father sitting in the Olds, his ear to the car radio, the summer the Germans marched into Poland. She was 12. “I didn’t understand what was going on but clearly it had import beyond rainbow trout,” she wrote. “The Olds was parked creekside… Daddy sat sideways in the car with the door open, a solemn look on his face, listening to the news.”

Like most things in her life, Denise’s memories of her parents would be intertwined with automobiles. The way her father hated to stop for gas, for example. (“Daddy was a champion avoider. As a child, I thought everyone routinely ran out of gas, because we did. Daddy strove to wean every car he drove.”) Or the way, in bad weather, he wrestled “to keep tall wheels lightly aimed on a slithering pathway, solemnly seeking higher ground.”

She had always been drawn to sport. “I like to experience those clear neon-lined moments of being truly tuned in,” she wrote. “And I like to watch the concentration of energy in anything done purely—two good doubles teams ricocheting volleys at the net, the perfect ballooning of a spinnaker, a kid bending a skateboard around a corner—golly, a Frisbee that doesn’t wobble! Beauty is a tremor of the spine.”

Growing up, her first love was football—tackle, not touch. On hard Kansas vacant lots after school and all-day Saturdays, Denise showed up to play, gravitating not to the glory role, but the brutish ones. “I liked to block,” she recalled. “I liked that hard contact. That force hitting force. That unequivocal confrontation that said, ‘This is Me; that is Not Me.’” But she knew her football days were numbered. Girls did not play football. It wasn’t acceptable.

She was never unaware of the complexities of being a strong girl. Her first best friend was a boy named Sammy Barnhill. They rode scooters and bikes together, and signed secrets in blood. But then, he had a birthday, and invited only boys to the party. “I was so convinced there had been a mistake I cried my eyes out,” she recalled. “Well, they let me go along after all. But it wasn’t the same.” Later, she told an interviewer, “There were no boys in the family, and I awfully wanted to be one.”

She was grateful, then, that the state of Kansas let her get her driver’s license at 13. She learned on her mom’s maroon “little” Olds—the first of the so-called Hydra-matics, or automatic transmission vehicles. She adored the physical sensation of driving, which reminded her of skiing. Driving hard into a turn, slashing the steering over, holding it, heading one way but going another? It just felt so right.

“I do like being pinned to the seat with the sudden application of G’s, and hanging there as the trees blur to a wash of peripheral green,” she wrote. “But speed when spooled to a steady three-digit state oddly becomes the hum-drum norm…Change is necessary to revive sensation. Getting up to speed is more involving than being there.”

9:58 a.m., 64 cars

“Two minutes!” The voice of Sebring’s founder, a promoter named Alec Ulmann, could be heard on the public address system. “Two minutes until starting time!” The cars—their numbers emblazoned on their sides, black numerals inside white circles—were parked along the pit side of the track. “45 seconds!” The drivers lined up opposite their cars, behind a painted line. “30 seconds!” Against a backdrop of signage-covered grandstands—banners touted Goodyear and Pirelli tires, Champion spark plugs, Mintex brake and clutch liners, and Gulf Crest gasoline—it was as if everyone took a collective breath, and prepared to sprint. “15 seconds! Thirteen, twelve, eleven…” During these moments, McCluggage would later recall, there was no small amount of “twitching, arms swinging, pivoting, heads twisting, then purposefully crouching.” Then: “Ten! Nine! Eight! Seven! Six! Five! Four! Three! Two! One! Go!”

With that, the drivers dashed to their vehicles. Those with open-topped rides vaulted into their seats, placing a hand just before the windscreen and leaping in. The others flung open doors before slithering under the wheel. Then, they lit up and roared off. To this day, this is known as a classic Le Mans start, a reference to the world’s oldest active endurance sports car race, held annually since 1923. Here’s what the standing start looked like:

[youtube:https://youtu.be/4opngvqiuFk?t=50]

McCluggage was good at standing starts, so she was in the thick of things right away. She put her Ferrari—No. 12—into gear as the whine of 64 engines filled the air. Amid this cacophony, one car sat idle: a Maserati driven by Sir Stirling Moss—one of the great British drivers, in his gleaming white helmet—had a dead battery. As mechanics rushed to make things right, the Corvettes took an immediate lead, passing under a bridge crammed with photographers perched like birds overhead. Then Masten Gregory, an American racecar driver known as “the Kansas City Flash,” surpassed them in another Maserati. Maseratis would lead for the first four laps, but after that, it was all Ferrari. The race was on, and McCluggage was behind the wheel.

Denise McCluggage left Kansas for college in California at the age of 16, and four years later, she graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a philosophy degree from Mills College. It was 1947, and she had decided she wanted to write for the San Francisco Chronicle. As a rule, they didn’t hire women reporters, but she was undaunted, pestering the editor of the Sunday magazine, visiting him almost daily. Finally, he relented. Her first job was in the advertising department, but after she joined the staff softball team and pitched like an ace, she was given a chance to write.

Her first pieces were so called “women’s features”—“Sob-sister stories,” as she put it, “The tearful lost-child things.” But that would change after she fell in with a reporter for the Oakland Tribune who was deeply into Midget car racing, which was all the rage then in California. These races featured very small vehicles with very high power-to-weight ratios, which meant they could really fly. McCluggage was hungry for lap time, so after the last heat, the guys—they were all guys, except for her—would let her drive the cars until they ran out of fuel. When she heard about a Midgets driving school, she thought, “I’ll do a story on it,” and her editor, a car buff, gave her the green light. Years before George Plimpton would be credited with inventing “stunt” journalism, attempting the sports about which he wrote, McCluggage was turning the things she loved to do into riveting prose.

McCluggage and two friends from Mills shared an apartment on 18th Street, in the San Francisco neighborhood that would later be known as The Castro. The place was above a garage, with bay windows and a dining room with two pianos (her roommates had concert aspirations). Sometimes those pianos attracted Dave Brubeck, who lived upstairs with his wife and their new baby. Brubeck had yet to record a record, but he’d invite friends over to jam—Paul Desmond, Cal Tjader, Ron Carter, to name a few. Their concerts kept the apartment’s record player superfluous, McCluggage liked to say.

She frequented the city’s many small clubs, seeing Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, George Shearing, Woody Herman, Nat King Cole, Cab Calloway, and Bobby Short. One night, when she told Billy Eckstine that he made up 75% of her record collection, he kissed her on the forehead. At the Blackhawk, a club in the Fillmore District where she could often be found at the bar, sipping a Coke, she loved to listen to the great bass player Vernon Alley. “I knew he had spotted me,” she recalled, “when he played “Exactly Like You,” a favorite of mine.”

She bought her first car—a ’36 Chevy that often jumped out of gear when she hit the brakes—for $100 from an editor at the Chronicle. Its front passenger seat was missing, the upholstery was stained and ripped and the head cloth was hanging in tatters. But when she was done with it, it was grand. She re-carpeted the floor with oriental remnants, reupholstered the seats in a classy striped fabric, and used a sailmaker’s needle to repair the top by hand. Then she was approached by another editor who had a 1926 Dodge sedan that he had bought for parts. The car, he’d decided, was too good to junk. Did Denise want it? She paid him $15 and was suddenly a two-car family. “The advantage of having two cars,” she would say, “is that you can look for parts for one of them in the other.”

But the car that would forever evoke her best days in San Francisco was a black MG-TC. She first encountered it on a visit to a showroom run by Kjell Qvale, one of the nation’s first importers of what were then called “foreign cars.” She was instantly smitten by what she described as that “loose roller skate of a car. Low. Perky. Absurd. Black. Swoop-doored. Red upholstery. Walnut veneer dash. Bumpers like tiny goalposts.” Tent-topped and tiny, with manual windshield wipers, long running boards, and a steering wheel on the right, the MG-TC—she named it “McGee”—was priced at $1,795. Her folks lent her the money, and the car was hers. She was 22.

10:05 a.m., 65 cars

As the rest of the field pushed towards the one-and-a-half-lap mark, Sir Stirling Moss finally started his Maserati and joined the race. He was dead last and therefore, as one reporter noted, “mad enough to break records.” Maseratis in these days were speedy, but unproven. Ferraris and Porsches were seen as reliably fast and unstoppable.

Behind the wheel of her Ferrari, McCluggage was putting her skills to work. In racing, there is this accepted wisdom: your concentration is safe if your mind stays focused on anything that moves along with you, or is coming up ahead. Accordingly, she’d learned to let drop any interest in anything stationary as soon as she passed it. If you could master this, there was this reward: “Your immediate environment is kept in an even wash of awareness,” she’d say. “Your attention creates a smooth, bland field against which the smallest changes emerge immediately.”

At 10:15 a.m., the leaders of the pack were so tightly bunched together “you could toss a blanket over the first four cars,” the announcer boomed into the microphone. McCluggage wasn’t among them, but she was holding her own.

What motivated her? Prize money? She wouldn’t turn it down, of course, but there was more at stake. Any driver who won at Sebring enjoyed huge bragging rights. But a female winner would enjoy that and something more. Though she preferred to prove herself through action, not argument, McCluggage took pride in showing that women were as capable as men. Would she prove that today? She could only hope. She drove on.

A girl must keep her priorities straight. In 1951, an opportunity in Boston caught McCluggage’s attention: a six-week course on book criticism at Radcliffe. When her bosses in San Francisco balked at giving her the time off she desired, she quit, sold her MG, and headed east. “I needed money more than I needed a car,” she would explain.

Arriving on the East coast at the age of 24, McCluggage knew her ultimate goal was to work for the New York Herald Tribune, a paper known for letting its writers write. The Tribune was the home of Marguerite Higgins, the most famous woman journalist in the country. It took her a while to finagle an opportunity to come aboard. Again, she started out in the women’s feature section, covering fashion shows.

That same year, 1953, she married an actor named Michael Conrad. They shared a tiny fifth floor walkup in Greenwich Village, living on her income while he auditioned for roles. They had a broken-down greyish Chrysler convertible, probably a ‘38. One summer day, as they were trying to escape the city heat by fleeing to the beach, the engine died hardly 50 feet from their Cornelia Street apartment. “I bet I know what that is,” McCluggage said, jumping out and lifting the hood. “Don’t you dare touch that. I forbid it,” Conrad barked. He was big, 6’ 5”, and his voice was forceful, with thunder in reserve.

“Get back in here!” he said, as McCluggage froze in place. “But Mike,” she said, “I can fix it.” Whatever was wrong that day had been wrong before, and she’d paid attention to how their mechanic remedied the problem. Still, Conrad’s voice dropped to a bark. “Get back in here!” he repeated. “I’m not going to sit in this car with a woman poking around under the hood!”

The marriage lasted just 11 months. The Chrysler wasn’t the reason for their split, but it was certainly symbolic. “At first I had enjoyed the challenge of playing chameleon and turning myself into whatever color necessary, but soon my energies were depleted beyond rejuvenation,” McCluggage reflected. “And so it ended.” Much later in his career, Conrad became known for his featured role on the TV police procedural Hill Street Blues. He played Sgt. Phil Esterhaus, who ended roll call each morning with the warning: “Let’s be careful out there.”

For her part, McCluggage, too, would be careful. She was 26 years old and she would never marry again.

10:18 a.m., 64 cars

Just 18 minutes into the endurance race, the first car was disqualified. An oil pump went kaput in a Ferrari Testa Rosa driven by the American drivers Pete Lovely and Jack Nethercutt, and the car was pushed off the track and into the pits. McCluggage couldn’t help but see it when she zoomed past. It would be more than an hour before she would pull into the pits herself, to give her co-driver a chance behind the wheel.

As a tenor sax player of note, Eager had been strongly influenced by Lester Young, whose light touch was widely admired. Jack Kerouac would immortalize Eager in his 1958 novella The Subterraneans, using him as inspiration for the bebop tenorman character Roger Beloit. Eager had been on fire in the 40s and 50s, playing with the likes of Charlie Parker and Stan Getz. One critic wrote: “Whatever he played swung with a happy, light-footed quality and pure-toned beauty.”

No wonder Eager and McCluggage connected so strongly: While driving, she sought out that same kind of rhythmic grace. She’d worked hard to prepare Eager for his first road race. She believed he was ready.

Denise McCluggage bought another MG-TC, this one red. It was her only transport, and she used it to travel all over the Northeast, weather be damned. It was 1955, and she’d gotten the break she’s been waiting for. A piece she had written on skiing from a woman’s perspective had caught the eye of the New York Herald Tribune’s sports editor, Bob Cooke. He offered her a full-time job writing about the sport. Cooke didn’t know it yet, but she also planned to write about motor racing, which few dailies covered then. “Racing was something I wanted to do,” she explained later, “so it was something I wanted to cover.”

All winter long, the Tribune paid her to travel the ski country of the Northeast, writing five columns a week. How did she carry her skis? Horizontally, of course. She had someone weld an open-ended metal box just big enough to hold the tails of a pair of Head skis onto the rear flank of the MG-TC. Then, on the front fender, she put a snug U-shaped bracket to grab the skis just shy of their curved tips. Viewed from the side, the skis might have been mistaken for a new-fangled racing stripe. The contraption worked nicely until the tip of the outside ski caught something protruding from a dump truck and snapped right off.

Come snowmelt, she sought out weekend sports car races and started a Sunday racing column. The column was rarely seen because it was often replaced with more pressing news after the early first edition. McCluggage didn’t mind. She was not only writing about the races, she was competing in them—and having a blast. It was, she would reflect later, a friendlier time, with no barriers between fans, journalists and drivers.

The world of sports car racing in these years possessed “a beautiful and paradoxical character,” Todd McCarthy explains in his book, Fast Women: The Legendary Ladies of Racing. “It was an elegant pursuit open to anyone who cared to engage it and on whatever basis you wanted; you could visit on weekends or succumb to it entirely; you could… do it just for the fun and thrills or take it very seriously indeed.” And, for a brief window of time, you could also be female. While the rest of the sporting world then viewed the rare woman athlete as almost freakish, car racing in the 1950s was oddly welcoming. Perhaps because of its rag-tag, upstart nature, the sport was wide open—a near-meritocracy. Sure, not all male racers applauded the few women in their midst. Stirling Moss, who would become one of McCluggage’s closest friends, admitted that when he first met her, before he saw what she could do, he was disturbed by the idea of a female behind the wheel. Other male competitors would reduce her to stereotypes, calling her “honeybuns”—and worse.

But McCluggage could drive. She had a certain economy of motion to the way she handled a car, never sawing the wheel, never pumping the brakes. Some racing aficionados talk about the ballet of driving, and McCluggage was a graceful pilot. And while she wasn’t one to boast, she had the gumption to engage with men on their near-exclusive turf.

Typically, when she could borrow a car, she slapped a number on it that she’d fashioned out of construction paper, as was the custom in weekend tourneys. After racing a few heats, and observing the heats of other racers, she would set up her pink portable Olivetti typewriter on a stack of tires in the pits and write up the day’s events, filing the story by Western Union. Asked how she made her deadlines, she said, “I used the adrenalin from the race to get the story out.”

As the weather turned warmer, McCluggage’s red MG-TC would open another door. She was about to walk into Joe’s luncheonette on West 4th street in Greenwich Village to get a bran muffin when she spotted a ruggedly handsome guy with short-cropped hair leaning against a cream-colored MG-TC, chatting with another man. MG-TCs were comparatively rare in the U.S. in those days, so—having one herself—she stopped to listen. The guy – smartly dressed in chino pants and stark white T-shirt – was explaining that the new leather racing helmet he was holding had been sent to him by some friends in England. She found herself touched, she’d recall, by his almost waif-like quality—his delight and genuine surprise that his friend would send him such a swell gift.

The guy was an actor named Steve McQueen. He wasn’t famous—not yet—but McCluggage was drawn to the incongruity of his vulnerability, his cock-of-the-walk posturing, what she called “his jive talk.” “If there’s anything I’m a sucker for,” she admitted, “it’s incongruity.” They became an item, breakfasting at Joe’s and hanging out at her five-flight walkup around the corner. Sometimes they parked their two MG-TCs nose-to-tail on Cornelia Street. They had other things in common, too: McQueen, like McCluggage, was interested in racing (he’d been making some money competing in motorcycle races at Long Island City Raceway). Denise, like Steve, had studied acting at Sanford Meisner’s Neighborhood Playhouse. (She never got far, she’d say later, because her career was leading into areas she found more interesting than acting. One lesson she’d learned in acting class, however, was something she’d never forget: Don’t make it happen, let it happen.)

Their romance lasted just a few months. In late 1955, McQueen, then 25, headed for L.A. to try to break into Hollywood. McCluggage bought a red Jaguar XK-MC convertible. The Jag was heavy—not an ideal racing machine—but she lightened it before each race by taking the foam-rubber seat cushions out of the back. Within months, she was racing in her first Sports Car Club of America National tournament at a cone-marked airport course in Montgomery, New York. In race eight, a five-lap Women’s Race, she took first place with a 60.5-mile-per-hour time. In the story she filed for the Tribune, she did not describe her own win, but anyone who read her accompanying tally of race finishers could have figured it out. It was August, 1956. She was 29. And suddenly, for the first time, she was a driver to watch.

11:55 a.m., 63 cars

Just before noon, a two-seater called an AC-Bristol flipped over—the second vehicular casualty of the day. Within the next two hours, eight more vehicles were sidelined for problems ranging from a loss of oil to broken steering to a blown engine. Among the drivers of those cars were some of the biggest names in the sport: Masten Gregory, who briefly led the field, was eliminated after his Maserati developed a suspension problem. Sir Stirling Moss, meanwhile, recovered from his late start only to bench his Maserati for good. His co-driver, Graham Hill, swung into the pits with feet frying from a broken exhaust manifold. Moss would nonetheless be credited later with the race’s fastest lap, at 97.4 miles per hour. But being fast wasn’t enough. You had to last.

At 1:53 p.m., an Aston Martin suffered a broken wheel. Where once there were 65 competitors, now there were 55, with eight hours more to go.

When you’re a woman driver, it can feel like you’re invisible. Denise McCluggage understood this better than ever while racing in the Bahamas Speed Week in Nassau in December, 1956. The course was partly old airport, wide open in some turns, and marked off with oil barrels. In the first heat, she drove a borrowed early Porsche 550 and won. But by the time the second heat came around, the Porsche was being used by another driver. A racer named Jim Kimberly kindly lent McCluggage his OSCA, but she promptly spun it. The race was over, for her at least.

Later, she would see a photograph of that spin in a magazine. The caption identified the driver as Jim Kimberly. Spinning was nothing to be proud of, but still, McCluggage was steamed. “I bought a packet of adhesive red polka dots and stuck them all over my white helmet,” she wrote in AutoWeek. “Now the world would know who was driving.” She would never again race wearing anything else.

In both the worlds of journalism and car racing, McCluggage tried to ignore the limits her gender placed upon her. She rarely complained, preferring instead to fight sexism with relentless persistence. It didn’t hurt that she still played football. She loved to tell the story of an impromptu game that drivers put together one year at Nassau. In the huddle, she was assigned to take out the great Texas racer Carroll Shelby. When the ball was snapped, she tucked and went at him. Whether his shoulder got broken or merely dislocated, she couldn’t ever remember, but she’d always recall something Moss told her at the pre-race party later that night: “I’ve got a list of other chaps I’d like you to play football with before the race."

“Look,” she wrote, “let’s assume—because it’s true—that some men race to prove that they are men. (I’m talking about weekend amateurs.) Then here comes a woman to debase that ego currency. I mean just how good are the macho points in racing if a female can do it as well or better? I was always maternally sensitive to the tender egos of the MRRDC (that’s how I referred to it—the Men’s Road Racing Driver’s Club.) After beating one of the members I’d pointedly say something to the effect: ‘Wow, your car was handling weird—it was understeering like crazy on that downhill right.’ How grateful were the smiles. Mind you, there was always a germ of truth in my words. I never patronize men. I beat them sometimes, but I never patronize them.”

In 1956, she went to cover the Indianapolis 500 for the New York Herald Tribune, but she was refused access to the garage area. It was obvious her gender was the problem. She protested and had a ludicrous back-and-forth with the officials that blocked her way. In her telling, it went like this:

Her: “See that fat bald guy going in? Do you let all fat bald guys in?”

Them: “Of course not. He has credentials.”

Her: “I have credentials!”

Them: “If we let you in we’ll have to let everybody in.”

She was getting nowhere when Frank Blunk, the motorsports writer for the New York Times, came to her aid. “If you don’t need the Herald-Tribune,” he told the Indy officials, “then you don’t need the New York Times either.” She got in, and thus became the first woman journalist to cover the Indy 500.

3:15 p.m., 52 cars

Here’s a truth about car racing that most of us don’t understand: Going as fast as possible isn’t the goal. It sounds counterintuitive, but the best drivers know that to win, you want to drive only as fast as victory requires. A racer’s ability to decide, even as his or her adrenalin surges, when to floor it and when to ease up determines victory or defeat, life or death. “Racing is something that must be done or not done,” she wrote in her regular racing column. “Every spin is a potential flip, every flip is a potential death. If you are going to race, race often. Keep the reflexes honed. Keep the hand in.” McCluggage knew this innately. But did her co-driver, Eager?

No records exist of precisely when McCluggage pulled into the pits and gave Eager his first turn behind the wheel of the Ferrari. Usually, such changes occurred when it was time to refuel, about two hours in. By that clock, he would have driven from noon to 2 p.m., then again from about 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. This much is known: once he got into the driver’s seat, he did just fine—at least in the beginning.

At 3:15 p.m., the race’s only Begra—a tiny American-made prototype that weighed just 630 pounds soaking wet—hit the skids. Its Florida-based inventors, Gene Beach (the “Be” in Begra) and Henry Grady (the “gra”), had recruited an eight-time Sebring competitor, John Bentley, to drive their 16-month-old upstart. But now engine failure sent Bentley permanently to the pits. Thirteen cars were out of the running. Less than seven hours to go.

Among women race car drivers in those days, Denise McCluggage was the best on the East Coast. The West Coast was dominated by Ruth Levy, a driver who’d gotten her start ice racing on the frozen lakes of Minnesota before moving to California. Denise kept hearing Ruth’s name and couldn’t help but wonder: could she beat her? The two women had never met when McCluggage called Levy with a proposition: How would she like to co-pilot a Porsche RS in the Venezuelan Grand Prix? It was November, 1957, and the duo would be the first all-female American team to be entered in an international championship race.

With Caracas as a frightening backdrop (the city was wracked by political unrest and was under virtual martial law), the race proved tumultuous. Every Maserati on the road wrecked, and American driver Harry Schell barely survived an explosion after his vehicle was hit by another racer’s wheel. But McCluggage and Levy’s all-female team was the toast of the town. Venezuelan fans threw flowers into their car every time they rounded a slow corner. And they finished strong, with a fourth in class.

In Caracas, McCluggage decided she was a better driver than Levy, but she kept it to herself. She knew the question of who was faster would be decided when, as she put it, they went “mano a mano.” It did a month later, when McCluggage again extended an invitation to Levy, this time for Bahamas Speed Weeks. They would race against one another in the Ladies’ Race.

McCluggage had never been wild about women’s-only races. They made her uncomfortable, she said, because they seemed to her “rather like mud wrestling, staged as a spectacle for men to chuckle over rather than serious competition.” But every race was a chance to drive, and for her, that outweighed what she called “the hair-pull aspects” of the tradition. She couldn’t pass it up.

Ruth was not only Denise’s chief adversary in the Bahamas, she was also her roommate. Such were the close quarters racers often kept. They knew what were driving: McCluggage would pilot a Porsche RS, while Levy had borrowed a 3.0 liter factory Aston Martin from Stirling Moss. The Aston Martin was more powerful, but McCluggage was happy to be the underdog.

Later, McCluggage wouldn’t recall the other four or five drivers in the race. She would only remember Levy, who blasted away at the start and went too wide in the first swooping turn. Driving behind Levy, McCluggage found herself “skittering along in the marbles”—small stones and tiny chunks of asphalt—and initially lost control, her car spinning. But she was lucky: after completing a full 360, she managed to resume the chase.

“Before the first lap was out I was back in the midst of it,” she wrote. “I knew then I could win—it was just a matter of picking the right place to pass so Ruth couldn’t get me back with the Aston’s superior acceleration.” Her plan worked. “I zipped past just where I had planned… We crossed the line with the Porsche’s nose no more than two feet ahead of the Aston’s.” That was just the first heat. In the second heat, Levy fared even worse, losing control and totaling Moss’ Aston Martin in the underbrush beside the track. She wasn’t seriously hurt, so when someone in the hospital asked her if she ran out of brakes, she was able to joke, “No. Brains.”

Later, Levy would say that of the 1950s-era women race car drivers, “Denise could have been the only one to go all the way.” Todd McCarthy, the author of Fast Women, concurred: “From the point of view of talent, intelligence, and guts, this rings true; if any American woman of that time could have cut it as an international race car driver of the first rank, it was Denise McCluggage.” No less than Stirling Moss agreed. “She was truly a pioneer,” he wrote in the foreword to one of her books. “Denise was important in elevating woman race car drivers from mere novelty and onto the grid of the Indy 500 and other important races.”

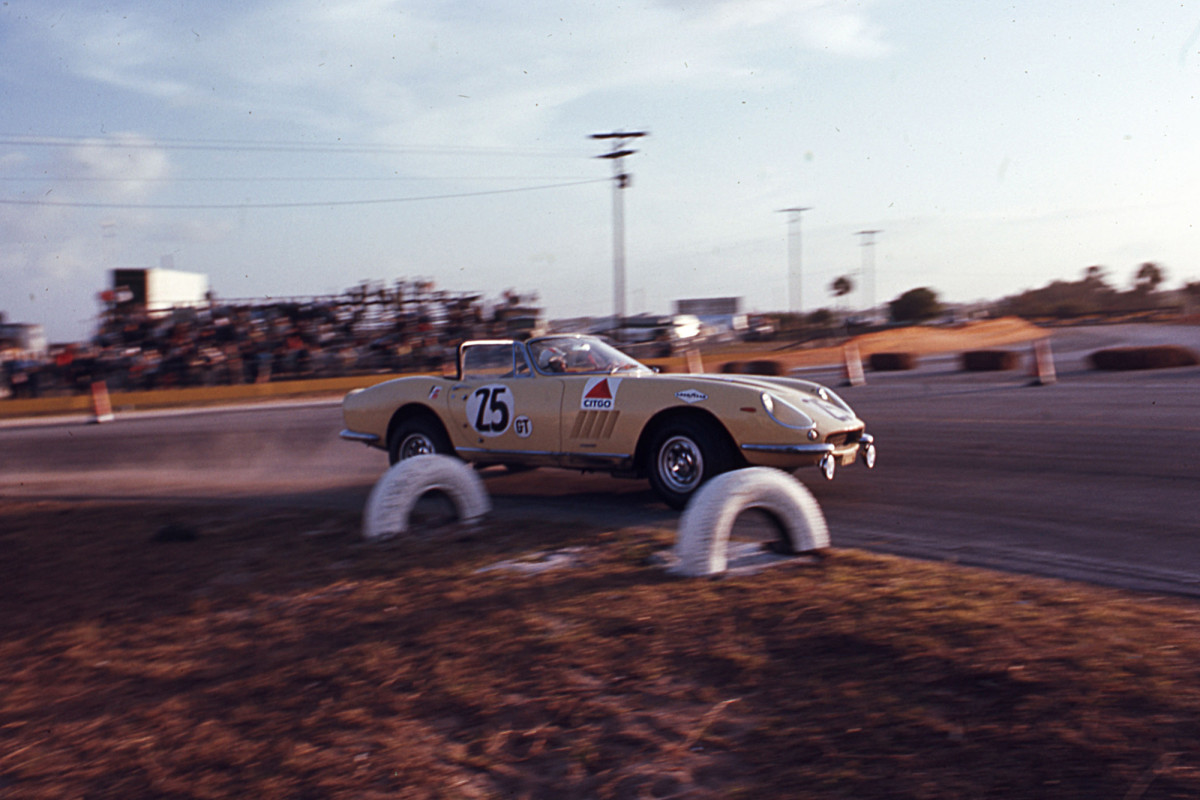

4:50 p.m., 47 cars

Does auto racing qualify as a real sport? McCluggage always believed passionately that it did. Race car drivers were no different than jockeys, she’d say. They were skilled pilots; you couldn’t win without them. When she made this argument, she often bolstered it with words she swore were uttered by Ernest Hemingway: “There are only three real sports—boxing, bullfighting and automobile racing. The rest are merely games.” She said a friend once confirmed this quote with Papa himself.

Still, like a jockey, a race car driver is nothing without his ride. Just ask Jo Bonnier and Dan Gurney. About seven hours into the 12 Hours at Sebring race, their mount—a Porsche RS-61—was sidelined for clutch failure. It was the 18th vehicle to leave the race. Bonnier, a Swede, had been racing competitively for 14 years. Gurney was one of the great American drivers. In years to come, he would become one of only three men in history to have won races in Sports Cars, Formula One, NASCAR, and Indy Car. In 1967, after winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans with A.J. Foyt, Gurney would spray champagne while celebrating on the podium. But on this day, he was out of luck.

So was McCluggage’s co-driver. Eager had fallen ill. Pulling into the pits, he surrendered the wheel for good. What exactly happened—Was he nauseous? Exhausted?—has been lost to history. But the consequences of his malaise were stark. From then on, McCluggage would drive without the possibility of a break, without back-up. There would be no rest. She was heading into the most dangerous hours of the race, the ones driven in darkness. Victory was now entirely up to her.

Officials at the 24 Hours of Le Mans generally frowned upon female competitors, but from 1930 to 1954, they’d allowed the occasional woman to enter. Then in 1955, a spectacular crash sent huge fragments of debris flying into the stands, killing more than 80 people and injuring 180. The crash was the most catastrophic in motorsport history, and in its wake, race organizers relegated women to the sidelines for their own safety.

Luigi Chinetti wanted to change that. Chinetti—who ran Ferrari’s North American Racing Team—had one rule he lived by: Any time a Ferrari won, it was good publicity. He didn’t care who you were or what you looked like—if you could drive, he wanted you on his team. In 1958, he asked McCluggage to drive for him at Le Mans. Since Chinetti had won the race himself three times himself, he hoped he could influence race officials to relent. The French had other ideas.

McCluggage was with Chinetti when he made a strong case on her behalf to the man in charge at Le Mans, one Monsieur Accat. Her French wasn’t great, but she needed no translation to interpret Accat’s stiff little head shake and his tight, narrow lips. “This is an invitational race,” the official decreed, “and we do not choose to invite women.”

She was not the only driver to be excluded. Chinetti had hoped to pair two Mexican brothers, Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez, in an OSCA in the same race. But Ricardo was only 15, so the organizers also said “Non!” to that. Denise encountered the brothers in the pits before practice at Le Mans. When Pedro told her why Ricardo wasn’t driving—“Too young,” she quipped. “No women or children allowed.” Pedro translated that into Spanish for Ricardo, who got a kick out of it. After that, every time she saw Ricardo he’d flash his wide smile and pipe up, in English: “No ladies or babies!”

McCluggage later observed that Pedro took his banishment in better spirits than she did hers. But there was an easy explanation for that, she said: “He knew that a year would change it all for him. And I knew nothing would change it for me.” It is striking that in all McCluggage’s writings, that pointed reference to the seeming intractability of sexism – “nothing would change it” – is unique. In her columns, while she often noted the pushback she got from some male overseers or rivals, she usually did so cheerfully, as if to say: “No worries, silly boys! I can take it.” But make no mistake: for McCluggage, as for every woman, taking it required a near-constant tamping down of disappointment.

She would try more than once to get permission to drive at Le Mans. She would never succeed. Not until 1971 would another woman drive at Le Mans.

Dusk, 43 cars

Just after 6 p.m., all racers were alerted to the coming darkness by a “Lights On” sign posted at the gate. Minutes later, Phil Hill made his move. For hours now, Hill and his Belgian co-driver Olivier Gendebien had been in second place, running behind the Rodriguez brothers’ vehicle. Both cars—No. 14 and No. 17, respectively—were Ferrari Testa Rosas. When the Rodriguezes’ vehicle made an 18 minute pit stop to fix a failed generator, however, Hill got the chance he needed. The soft-spoken Floridian, who would later become the only American-born driver to win the Formula 1 championship, moved into first place.

If McCluggage was aware of this, it no doubt made her happy. She and Hill were dear friends. They’d traveled together to Modena, Italy, where the Ferrari factory is, and she credited him with teaching her a little about the mental discipline upon which the best racers rely. “I mailed that letter,” Hill would often say, referring to how his mind worked behind the wheel. McCluggage thought she knew what he meant: “Any error was forgotten, its power to interfere with his concentration now ended. It’s a good image. Drop a letter in a corner slot and it is out of mind.”

She needed such wisdom now, as she sped around the course. Four more vehicles were out—an OSCA, a Ferrari, a Porsche and a Maserati—felled by transmission trouble, a broken camshaft, and gear failure. There were nearly four long hours to go.

On a spring weekend in 1958, Denise McCluggage was in the pits at Cumberland, Maryland, to race in an SCCA National event (and to cover it for the New York Herald Tribune) when she was approached by two men from Detroit. They said they were starting a new publication for motor racing enthusiasts—one that would have timely race reports so readers wouldn’t have to wait weeks to find out who won a Grand Prix. Would she be interested, they asked, in writing for it?

Her first article in Competition Press appeared in its first issue, July 16, 1958.

At first she only moonlighted for Competition Press while continuing on staff at the Tribune. But then, it was announced that a notorious former Tribune sports editor named Stanley Woodward was returning. Before starting the job, Woodward, who was known as The Coach, was interviewed by Life magazine about his plans. “The first thing I’m going to do is fire that broad,” he was quoted as saying.

McCluggage was called back from the ski slopes to meet Woodard in his office. “I felt an immediate pity for this supposedly powerful man,” she recalled later. “He looked at his desk top, at his shoes, at the light fixture—never for more than an embarrassed second at me. He stammered. He didn’t know whether to call me ‘Denise’ or ‘Miss McCluggage.’…It wasn’t, he assured me, that he didn’t like my work or my writing, it was just that women did not belong on the sports page. He wanted me to move back to the women’s page from whence I sprang.”

Thanks, she told Woodward, but if it’s all the same to you, please, I’d rather take my severance pay and split. She knew exactly how she’d spend the money. “You see, I had been trying to figure out how I could wangle six weeks’ leave of absence to go to Europe and follow the Grand Prix circuit that summer,” she recalled. “Now here was the prospect of not only a leave of absence, but the wherewithal to finance the trip!”

7 p.m., 40 cars

At this hour, the leader board showed three Ferrari Testa Rosas on top: Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien still in first, Richie Ginther and Wolfgang von Trips (No. 15) in second, and the Rodriguez brothers in third. But McCluggage, who was competing in a different category, still had her eyes on victory. Her Ferrari Berlinetta was in the Gran Turismo class, not the Sports Cars. And now, she was leading the GT pack. For the first time all day, her car was in the top 10.

McCluggage’s main GT rivals now were the Corvettes—especially No. 18, driven by a Texan named Delmo Johnson and his co-driver Dave Morgan. Meanwhile, yet another three cars—a Lola, an Abarth 1000-GT, and an Alfa Romeo SS—had been disqualified. Twenty-five of the starting 65 cars were now out of the race.

After quitting the New York Herald Tribune in 1958, McCluggage covered races for Competition Press all over Europe. Then, she came home and stumbled upon a sure-fire way to get over on sexist bosses: owning the means of production. For a brief time, she became the proprietor of Competition Press—selling an Alfa she’d acquired along the way to buy out the founders for a price that equaled the printer’s bill they’d run up. When she returned from her travels, she put out the twice monthly journal in a storefront office across the street from her Greenwich Village apartment, keeping the paper alive for a year before offering John and Elaine Bond of Road & Track the same deal she’d made. They could take ownership if they got her out from under printer debt. Six years later, the title changed its name to AutoWeek, and McCluggage’s byline would appear in its pages for decades to come.

Later, she acknowledged, “Men who write about and talk about sports… have little notion how to work with, deal with, talk with women. Women—toe-to-toe, skill-to-skill women—baffle and befuddle nearly every man in the sports department.”

It wouldn’t help those men, surely, that she was becoming famous. In 1959, she was asked to appear on the relatively new TV game show To Tell the Truth. She and two other women introduced themselves to a panel, all claiming to be Denise McCluggage. The judges, who’d been told that McCluggage covered skiing and sports car racing and is “proficient in both,” interviewed the contestants about what cars they liked to drive, what ski jumps were the highest, and what editors they’d worked with. McCluggage was convincing; three of the four judges (one of whom was a young Betty White) guessed correctly. When the narrator asked, “Will the real Denise McCluggage please stand up?” few in the audience were surprised.

8 p.m., 40 cars

It was pitch black now, and that made for some unexpected beauty. In the darkness, disc brakes were visible through wire wheels as drivers slowed their vehicles down. Especially at the hairpin turn, friction made them glow red, then yellow, then bright white. Round and round everyone went, past the helicopters and prop planes parked on the shadowy tarmac, under the pedestrian bridge that straddled the track near the pits, past the endless palm trees and the huge “Martini & Rossi” banner near the finish line.

McCluggage was still tenth on the leader board, first in the GT class, with five Corvettes in hot pursuit. She knew she must remain in control. Driving fast over a rough course takes a physical toll. Sometimes, after a race, she was so beat up she’d have to carry herself gingerly, “like a stack of dishes.” The vibrations tired your hands and your arms. The heat strained your lungs. But she was a student of her breath—she sometimes prepared for races by doing yoga and standing on her head—and that would always serve her. Inside herself, she knew she could find a calmness.

At 9 p.m., with an hour to go until the finish, McCluggage’s car was ninth in the lineup, and things were getting more than a little surreal. “A woman is hard on the throttle at Sebring, moving into the night, out of the pits,” she wrote in a column recollecting the race. “The velvet night pushes against my headlights. In the passing dazzle I pick out a recognizable pit board to read my chalked lap time”—scrawled numerals she registered as “a primitive affirmation” of her existence. After so many hours, “my Sebring tapering to a close is like being alone in an old house during a storm; noises never heard before mock me. They disappear, leaving me listening intently to their absence.”

She was no stranger to this feeling. It was as if the very act of piloting a vehicle at top speeds for hours on end could bend time, morphing the surrounding landscape into a series of distinct images.

“Driving is what you are doing,” she once wrote of this sensation, which she’d experienced during her travels around Europe. “And the single-ness of attention to that makes even more intense the edge-of-the-eye glimpses of moments of life, on-going but frozen by your swift passing. A small boy in his grey school smock runs across old cobblestones on pipe-stem legs, a long baton of bread tucked under his arm. A centuries-old woman with a centuries-old round broom peers from under her shawl as the sounds of your singing engine sweep through her barnyard. A small village makes a brief canyon of your road. A man in an undershirt leans out of his second story window over a cafe to pull shut old wooden shutters. Behind him a fluted glass lily of a light fixture hangs from a high ceiling. Such a fleeting glimpse, yet in the moment that I pass I live in that room. I know its dim light and dark wood. It is a nano-second home to me.”

Now, she was engulfed in darkness. Her brakes were shot, she knew, and she was flying past the pit board again with just minutes left to go. Don’t make it happen, let it happen. Her world shrank to encompass only the gleaming pathway ahead. “In the darkness… I am somehow faster than I was in the first hour.”

How many times must she tell you that things were easier then? “You could meet a guy skiing at Hunter Mountain, discover he’d long fantasized about racing cars, ask, ‘Wanna drive with me at Sebring?’ and by race day, there it is,” she wrote. “So he was a jazz musician who had never raced. So you had no race car. But you knew where money and Ferraris came from, and you were into fulfilling men’s fantasies as far as you were able. You waved the wands.”

It was early 1961, and the guy Denise McCluggage met was Allen Eager. Square-chinned and handsome, he told her he was “cursed with flair” and that it had always been so. At three, he learned to read. At nine, he learned to drive after his mother caught him “borrowing” the local garbage truck for jerky midnight tours around the grounds of the small hotels she and her husband ran. At 15, he took his tenor sax on the road; he'd later play with Tommy Dorsey. But he’d had his struggles, and he told her about that, too. “On the curse side of precocity,” McCluggage later wrote of her new beau, “also at 15 he was introduced to heroin in the back seat of a Lincoln Continental by a girl singer. That tenacious woe was with him off and on for the decades to come.”

When McCluggage bumped into him, Eager had essentially retired from jazz. After living in Paris for a bit, in 1957 he’d recorded what would be his final album for 25 years. His reasons for quitting were related, he explained, to the death of Charlie Parker and his own problems with drug addiction. Thinking that if he could stay away from music he would also stay away from dope, he’d adopted the outdoor life, working as a member of the ski patrol at Hunter Mountain. It didn’t take many shared runs to spark their romance. He loved cars. She raced them. They both loved jazz. It was on.

What is it about jazz artists and fast cars? McCluggage would never forget the time in San Francisco when she was assigned to write about Mel Torme. When he saw her MG, he insisted on driving it. Eager was the same. So was his friend Miles Davis, who McCluggage would also get to know. Eager liked to boast that he once talked Davis out of buying a Mercedes by taking him to Luigi Chinetti’s Ferrari showroom on 11th Avenue and 56th Street in New York City. Just as they walked in, a Ferrari horn honked in the concrete garage, and the sound ranged from wall to wall. Davis stopped in his tracks, listening. “Man,” he exclaimed. “G and E!” A moment later, someone started the engine of a Formula One car, and that did it: Davis bought his first Ferrari.

For years, McCluggage, too, had been hanging around Chinetti’s showroom, communing with the cars, listening to the echo of their horns and hoping someone will fire up a racing V-12 and vibrate her brain pan. It seemed to her that there was something about the rhythm of shifting gears that drew jazz men near; they heard a certain music in an engine’s whine.

In 1960, Eager had emerged briefly from retirement to play alto sax with Charles Mingus at the Newport Jazz Festival. One critic pronounced him “rusty… [T]he old fire and fine timing were heard only in fleeting moments.” Apparently, it was time for a new challenge. Eager told McCluggage he had two wishes: one, to star in a Western; two, to drive a race car in competition. She was determined to make the second dream come true, but first she needed to convert him from a smooth, aware road driver into a bonafide racer. To do that, they needed a great car. “Maybe we should get you into a Ferrari,” Chinetti had told McCluggage more than once. Now, he helped her make it happen. To raise the necessary funds, she sold a Porsche 356 that she’d paid $3,500 for in Stuttgart. Then she headed straight to Chinetti’s showroom, where he gave her a terrific deal on that well-mannered Berlinetta. Sure, McCluggage said, she still lived in a tiny five-flight walk up. Sure, her furniture was Late Salvation Army and Early Unpainted. But this beaut of an automobile had won fifth at Le Mans in 1960, the year it was built. “I had my priorities straight,” she wrote. “The rent was controlled, pasta was cheap and I owned a Ferrari.”

She continued Eager’s education, taking him to Lime Rock Park, a 1.53-mile road track in Lakeville, Connecticut. Early on he balked—“You’re trying to kill me!” he said—but he soon was getting the hang of it, seasoning his smoothness with what McCluggage called “apt aggression.” So what did they do next? Something crazy: they signed up for Sebring, the world’s greatest 12-hour sports car endurance race.

10 p.m., 37 cars

“It’s just 10 o’clock now,” the announcer said. A few minutes later, the checkered flag fell for the first time as the Ferrari TR driven by Hill completed 208 laps, or 1081.6 miles, with an average speed of 90.133 miles per hour. The crowd applauded loudly. It was Hill’s third time winning the Sports Car class at Sebring. Soon, eight more sport cars— five Ferraris and three Porsches—came roaring past the post. Only then came McCluggage, bearing down fast. As she hurtled toward the finish line, she didn’t dare to breathe—not until she got the checker. “Downshifts and rapid pumps [got] me stopped,” she’d recall later. Her Ferrari had completed 182 laps and came in 10th overall and 1st in the GT class. Against all odds, with an ailing co-pilot and worn out brakes, she’d finally won. And it was fair to give her the lion’s share of the credit. Of the race’s dozen hours, McCluggage had driven seven and a half.

She could exhale now, but all was not well. McCluggage’s Ferrari had beaten a Corvette by two laps, but the factory-supported owner of the Corvette team was one poor loser, particularly to what he called “a damn woman.” So he filed a formal objection. One of the Corvette team members, a good guy, admitted later that they knew the Ferrari was the victor. “It was just cussedness that prompted the protest,” McCluggage wrote. For his part, Eager used his musician’s ears to size up the ‘vettes: “God, they have such a brown sound!”

McCluggage and Eager’s win came with a trophy and $2,000 prize money, and it was not long before they decide how to spend it. They paid $600 to ship the Ferrari to Europe, then flew to meet it, skiing awhile in Cervinia while they waited for the vehicle to arrive. Then they headed to Nurburg, Germany, to take part in the 1000 km Nurburgring race, in May 1961. McCluggage had raced the ‘Ring, as it’s called, once before, in an Alfa. So they arrived a week early to introduce Eager to all 187 turns, plus or minus, of the storied course. They stayed in the Sporthotel, right under the stands, eating like royalty. There were endless tortes, and the occasional Portuguese oyster drenched in lemon. “One bite,” McCluggage would remember Eager telling her of the delicacy, “and you’re 20 fathoms down.”

Eager was a quick study, but he had trouble with the course until McCluggage broke it up for him into musical movements. Then he got it down cold. Or so he thought until race day, when he popped out of the Karussell and hung the car on a fence. For them, the contest was over. McCluggage made the best of the wreck. “There’s nothing more hip than driving across Europe, back to Modena, in a Ferrari with bodywork pried away from the wheels and the shadow of a number on the side,” she wrote. Together, she and Eager took the wounded Ferrari straight to Scaglietti’s for an electric blue paint job with a white racing stripe. “That car was so blue,” she recalled, “it was red!”

For his part, Eager would never stop bragging about his racing prowess. “Oh, yes, I’ve raced the ‘rings,” he would say. “Seb and Nurb.”

March 24, 1962

Sebring, Fla.

1961 would not be McCluggage and Eager’s only Sebring as teammates. In 1962, they returned to the course to defend their title, driving one of the open-topped OSCAs that Luigi Chinetti kept in the back room of his Ferrari store in Manhattan. The race didn’t go well for them. McCluggage had a very slow start. Then, Eager spun the car, lost control and collided with another car. They were out.

But Sebring ’62 did give McCluggage another glimpse of McQueen—then a well-known TV actor on his way to becoming a movie icon. McQueen was driving an MGA for what was then called the British Motor Corp. in the race, and he greeted Eager, who he knew from his days in Greenwich Village, warmly. “Hey, man,” the actor said, leaning in conspiratorially, “I bet we’re the only two guys in this race who ever…” and he mimed taking a puff of marijuana. Happy to oblige, Eager reached into his pocket for a joint, saying, “It just so happens…”

It was a friendly gesture, but McQueen was aghast. “Hey, man, what are you doing?” he asked, glancing around nervously. McCluggage later said she understood McQueen’s reluctance to light up in public. While Eager thought it proved McQueen had morphed into a “Hollywood hypocrite,” McCluggage felt that wasn’t fair. “To me it meant Steve had Made It and wanted to Keep It,” she wrote.

Undoubtedly, there was more than a little macho rivalry at work in the exchange. After all, shortly after McQueen arrived at the race track, he’d sidled up to McCluggage, flashed a smile, and whispered in her ear: “I’m falling in love all over again.” Her response: a hoot of laughter. McQueen looked a little hurt at first, but then he laughed too. McCluggage would recall: “It was a damn good line, and he had delivered it well, and I had loved it. But we both knew it was a stranger to any truth—either at the moment or long before.”

Later, McCluggage would recall the precise moment when she realized that her cherished upstart of a sport was growing up. It was at Meadowdale Raceway, in Illinois. “I knew things were changing when I drove my Ferrari from New York City to Chicago, all alone, no mechanic… and I saw that my competition, two Corvettes, had arrived on a double-decked trailer. I said, ‘Oh, no, this is different.’ I knew I’d never be able to compete with that.”

In 1962, during a preliminary 10-lap race a Thompson Speedway, a demanding two-mile asphalt course through hilly terrain, she abruptly decided to sell the Ferrari. “I was wheel to wheel with Dick Thompson driving a Corvette,” she recalled. “We were headed into the first turn, and I knew he’d chop me off if he could. I thought, I can’t bend this thing. I braked hard, but Dickie still hit [my] left front headlight rim and sent it spinning. Clearly, I could not race my apartment, my winter coat, my all… You see, it was not only my only car, it was my only thing. Crashing it would have wiped me out.” After the race, she walked over to a driver named Bob Grossman who she knew. “You’ve been coveting my car,” she told him. “Well, it’s yours.” And she went home. She didn’t even race in the finals.

March 26, 1966

Sebring, Fla., 2:40 p.m.

Five years after McCluggage and Eager’s GT win, some of the same drivers they competed against in 1961 would again enter the 12 Hours at Sebring. Dan Gurney. Graham Hill. Jo Bonnier. Denise would not be among them.

The 1966 race would be a showdown battle between Ford and Ferrari. But at 2:40 p.m., tragedy struck. A 32-year-old Canadian driver named Bob McLean, on approach to the course’s hairpin turn, had the gearbox on his Ford GT40 seize up, locking the rear brakes. The car crashed into a ditch and barrel rolled into a telephone pole. McLean died in the fiery explosion.

The race went on, but a few hours later, there was another disaster: Mario Andretti’s Ferrari 365 P2 tangled with Don Wester’s Porsche 906 on what was called the Warehouse Straight, sending the Porsche plowing into a group of spectators. Four fans were killed.

The five deaths prompted big changes to the circuit’s layout that would make the course much safer. The hairpin turn, for example, was removed. No one would ever again race the course where McCluggage and Eager prevailed.

McCluggage sold her beloved dark blue “mouthful of a car” to Grossman for $6,000 and a used, pale-colored Mini of what she called “uncertain history.” It seemed like a fair deal at the time. But for the rest of her life, she would miss that car. In 1970, she would admit to an interviewer that sometimes, late at night, she could still hear the thrumming sound it made during the first fast bend at Sebring. In 1975, she would see it for sale—with a new red paint job—and wish she could afford its $185,000 price tag. Wouldn’t it be nice, she often thought, to drive something again that blurred the trees?

Even after she and Eager took what she liked to call “separate roads,” McCluggage competed in many other races. In 1962, she would speed across Canada in a Corvair. In 1964, she would drive a Mini to Moscow from London, via the Scandinavian countries, and escape a threatened mugging by handing out jazz records she kept in her trunk. While living in England, during much of 1963 and into 1964, she drove for BMC, Rover, and Ford, doing such rallies as the RAC, the Tulip, the Acropolis, the Alpine, the Liege-Sofia-Liege, and the Monte Carlo (in that one, she and the legendary British driver Anne Hall, aka “The Flying Yorkshirewoman,” won their class in a factory Ford Falcon).

And then, in 1967, after competing in one last 12 Hours at Sebring (she and co-driver Marianne “Pinkie” Windridge came in 17th), McCluggage quit racing. She would never stop writing about cars, and about driving, and skiing, and how the mind and the body must work together to achieve the beauty of perfect movement. But when asked to explain the end of her career as a driver, she said that racing had always been, for her, a means to something else. “For me, it was a path,” McCluggage told one interviewer, “rather than a destination.”

McCluggage chronicled the evolution of auto racing from an oddity “as obscure to the general public as championship tiddlywinks,” to a high-stakes, big-money sport. Over 60 years, no one would document the sport more diligently. No one would capture more poetically what it felt like to drive at high speed.

And yet, for all she did to make sports car racing a household name, when she was 79, she described the way she approached her racing days as freelance, but “more ‘free’ than ‘lance.’” That, she knew, was not how the best drivers did it. As she’d told her readers so many years before, racing is something that must be done or not done. Devote yourself wholly, or pull into the pits.

When she was 84, she nudged at the same idea—her unwillingness to forsake all other interests for racing—in her monthly column in AutoWeek. “My own racing—dare I admit it here—was sort of a tai chi with cars that found me spending many weeks at Esalen,” she wrote, referring to the famed retreat center in California’s Big Sur where she would study Chinese traditions of movement and meditation. Later, she’d master an approach to psychotherapy and wellness called neural linguistic programming. She wrote a book on skiing and mindfulness, The Centered Skiier. She learned to pilot airplanes and to jump out of them with a blank-gore chute. At some point, she’d had cards printed that read, “Consultant: Any Subject.” Her curiosity wasn’t singular. And she loved racing too much to do it halfway.

It’s a funny thing about racing memories. Even into her eighties, Denise McCluggage could recall with startling precision just how the asphalt changed color at a cut-off point on Germany’s Nurburgring Track or how many revs there were between second and third gear on a particular car. But at times she couldn’t remember whether certain events happened in one year or another. Her advancing age was not to blame: her mind was sharp. It was the round-and-round repetitive nature of racing itself that forged unique pathways in her head.

As the years passed, she would admit that chronology had a lesser hold on her remembering. More and more, she wrote, “I can’t remember whether a certain thing happened one year or another, or whether that was before Mac died. Or Behra. Or Peter. I tend to bring order to memory based on what I was driving at the time.” She had owned, in no particular order, a double-bubble Fiat-Abarth, a Jaguar, an Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint Veloce, a Porsche, a string of Mini-Coopers, and a Lancia (not to mention a Land Rover, a Subaru, a Mitsubishi, and countless other cars). She wrote in AutoWeek that people kept telling her,“If you woulda kept all the cars you’ve owned, you’d be a millionaire.” But “they have it bass ackwards,” she said. “If I’d been a millionaire, I would’ve kept all the cars I’ve owned. OK, some of them anyway. Some didn’t deserve it.” She always said the Ferrari that carried her to victory in 1961 deserved it most of all.

In 2011, half a century after her win at Sebring, she asserted that “March 25 was my 50th anniversary.” She was not talking about a wedding. She had long been single, and happily so. Her achievement was different, she wrote: “Fifty years ago, I won a race.”

Four years later, she filed a column that would be her last for AutoWeek. She wrote about dirt roads in bad weather—“torrents pouring from bruise-black skies.” She remembered “distant Kansas farm roads and my daddy wrestling to keep tall wheels lightly aimed on a slithering pathway, solemnly seeking firmer ground.” Then on May 6, 2015, five days before the publication of that final column, Denise McCluggage died at the age of 88.

The racing world mourned. “No one else brought the perspective Denise offered,” wrote her colleague Mark Vaughn. “She was there when Phil Hill won Le Mans, driving around the track with him the night before… She was there when [Argentina’s Juan Manuel] Fangio and Moss were winning Grands Prix across Europe.” Another colleague, long fascinated by her near-mystical ability to cure headaches or eliminate AutoWeek staffers’ addiction to cigarettes, remembered her as nothing less than a shaman. To be sure, she’d accumulated her share of wisdom. As she’d told her readers: once, on a “dark, late, lonely backstretch at Sebring,” she’d had what she called “my own petite epiphany.” It went like this: “The slower your breath, the faster you go.”

Denise McCluggage was the author of several books about driving and skiing. She is the only journalist to have been inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame (2001). The recipient of many automotive journalism awards, she was added to the Sebring Hall of Fame in 2012.