Fueled by Star Power, 'Ford v Ferrari' Captures a Bygone Era of Ingenuity

For a movie called Ford v Ferrari, the cast—at least the marquee duo—offers very little in the way of gearhead credibility. "I grew up taking public transportation," says Matt Damon. "I mean, nobody had cars. Ben Affleck got a car, a '73 Toyota Corona. It had holes in the bottom that had rusted out, and you could watch the pavement go by. This car was such a piece of s---. He bought it I think for a couple of hundred bucks. We used it for years, and then it got towed."

When they realized the tow charge was more than the car was worth, they didn't bother to retrieve it. Says Damon, "Ben saw the tow truck driver from Pat's Tow in Cambridge [Mass.] driving his car, because the guy just assumed nobody was ever going to come to get it." Affleck went in and gave Pat an earful, but at the end of the day let him keep the car rather than pay the fee.

As for Damon's co-star in Ford v Ferrari: If you Google "car Christian Bale drives," one of the first hits is a slide show titled "15 Filthy Rich Celebrities Who Drive Garbage Cars," including a photo of Bale in his beloved 1992 Toyota Tacoma. "I take exception to my car being called garbage," Bale said during a late-summer photo shoot. "It is indestructible."

When he's reminded that he was late for said photo shoot because the Tacoma had a dead battery, Bale is quick to point out that it was his fault, not the 27-year-old pickup's: "I was doing something with it, and my son said, 'Look, there's a centipede.' And I ran to see the centipede with him and just totally forgot about my car. And then this morning it was like, Yeah, nothing."

Since waiting for the battery to charge would have made him even later, Bale went to a nearby gas station, picked up a new battery and installed it himself. "Ken would have been proud," he said with a smile.

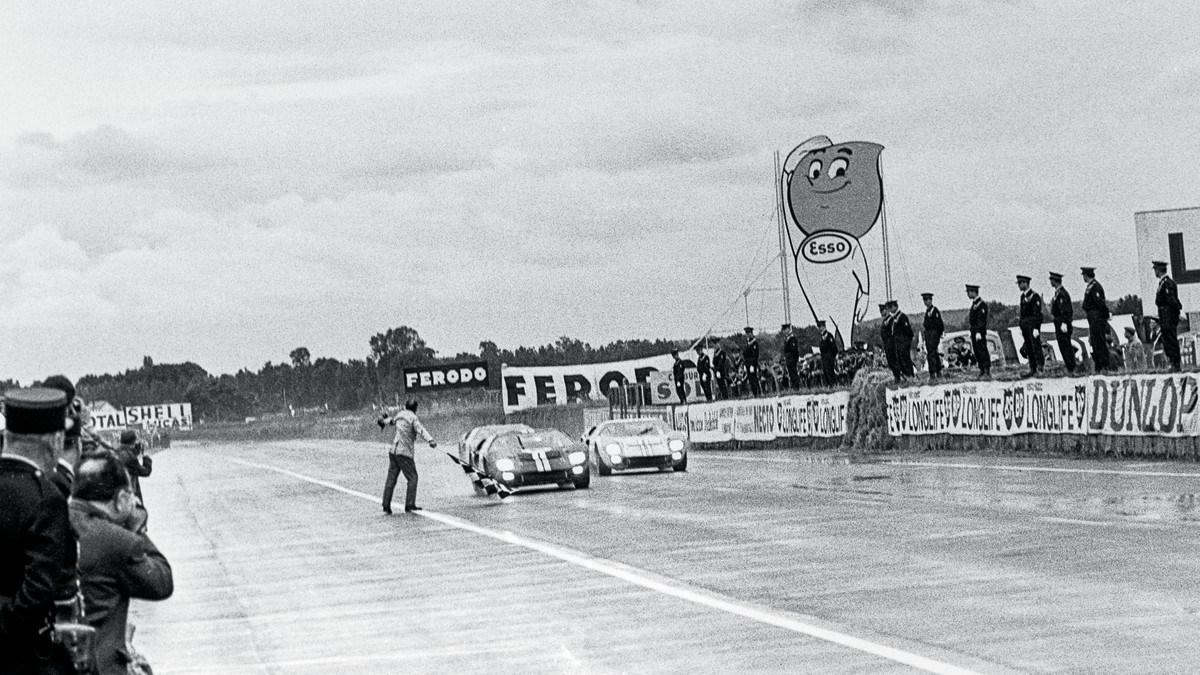

Ken is Ken Miles, the British mechanic and racer handpicked by Damon's Carroll Shelby to drive his Ford GT40 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966. While their quest to end Ferrari's dominance gives the movie its titular battle, what elevates the film beyond compelling underdog fare and into Academy Award conversations are the ancillary battles—not the least of which is the internal struggle to persuade the Ford suits that the headstrong Miles is the right, if not only, man for the job.

In that regard, it's fitting that Bale was the choice to play Miles, whose interest in making a career out of driving didn't extend far beyond the cockpit. "Christian really, really shares a huge amount of personality traits with Ken Miles," says director James Mangold, who first worked with the Welshman 12 years ago on 3:10 to Yuma. "He loves the art of acting, but he doesn't like marketing. He doesn't particularly take interest in how many people are going to see the movie as much as what he gets out of the process of playing a part. It's a very artistic, inward journey for him, about getting something right by his own standards, not for other people's." (To be fair, it bears repeating that Bale bought and replaced a car battery so he could do p.r. for the film.)

As Miles puts it simply, "I'm not a people person," which leaves it to Shelby—an affable Texan equal parts mad scientist and huckster who unloads "Steve McQueen's car" on three different customers—to sell the brass on Miles. "That's one thing people told me [about Shelby]," says Damon. "He could sell absolutely anything. You'd walk away with something that you didn't need, and you'd be really happy having bought it from him."

To inhabit the character of Miles, Bale shed the 70 pounds he had gained for his Oscar-nominated turn as Dick Cheney in Vice. "I've gained weight and lost weight—not to that extent—for roles, and there's always a new theory, a new kind of way to do it," says Damon. "I said [to Bale], 'Well, so what'd you do?' And he looked at me—he's dead serious—and he said, 'I didn't eat.' And I realized, that actually was all he did."

The other significant battle in the film is much larger in scope: man versus his natural limitations. Ford v Ferrari takes place in the late 1950s and early to mid-'60s, when engineers and scientists relied on their ingenuity as much as the evolving technology at hand. Shelby and Miles don't test their cars in a wind tunnel, and when an Igloo cooler--sized computer riding shotgun in the GT40 fails to adequately diagnose an aerodynamic issue, they Scotch-tape balls of wool all over the car to study the airflow. When overheating brakes become a problem, the solution isn't a magical heat-resistant polymer: It's finding a loophole in the rules that allows for changing the rotors and pads during a race, something Ferrari had never considered.

"For me, what's really magical and transporting thinking about that period in time is we're forced to take stock of how the computer has changed our lives, for better and worse," says Mangold. "That voyage of discovery, of engineering, that trial and error in building machines precomputer, was a kind of a science, but also an art in which there was an alchemy and an instinct for these math geniuses—how they could feel and hear and sense this vehicle. There's something deeply romantic to me about a moment where people are making discoveries off their gut instincts as opposed to staring at a monitor."

Not coincidentally, the Ford-Ferrari conflict took place at the same time as another international scientific showdown: the space race. "It felt like a kind of The Right Stuff, with cars," says Mangold. With all of the crew cuts and short-sleeved button-downs, his film looks the 1983 classic, too. (Especially Jon Bernthal, whose young Lee Iacocca could be the missing link between Scott Glenn's Alan Sheppard and Fred Ward's Gus Grissom.)

Indeed, it's not hard to draw a line from the test pilots—Shelby was one near the end of World War II—at Edwards Air Force Base to the Venice Beach hot-rod culture 100 miles to the south. Says Damon, "They were this whole community of young guys who were into just building bigger engines and making s--- go fast."

***

Let's be honest here. As great as character development is—and in Ford v Ferrari, as Bale rightly points out, "the characters are so much bloody fun"—it's not nearly as awesome as s--- going fast. And when it goes fast on screen, it's enthralling (and dizzying).

Bale and Damon got their first up-close taste of auto racing in May, when they went to the Indianapolis 500 and served as the ceremonial starters. "I have to confess, I felt like, I'm interested to go, but we're probably gonna feel like prats up there, waving that green flag, you know?" says Bale. "But oh, bloody hell—we got to be above the track. You feel the vibrations as those cars are going through."

Damon rode around the Brickyard at 190 mph in a two-seater with Mario Andretti. Bale—formerly an avid motorcyclist whose daughter has forbidden him to ride after one too many wrecks—demurred. "I've gotta be allowed behind the wheel, or on a motorcycle," he says. "I had a few offers when I was riding from incredible riders who I was lucky enough to find myself on the track with: Hey, jump on the back. No, mate, not doing it. Can't do it. I just can't put my life in someone else's hands, no matter how brilliant they are."

Bale did get to go behind the wheel at driving school in Phoenix and to take a Cobra for a spin around a racetrack in Willow Springs, Calif. "Oh, that's so much fun," he says. "The back end slides right out!" In the movie, though, he and Damon logged little meaningful time behind the wheel. "I drove less than I would have liked, but more than the insurance company would have liked," Bale says. "There's always that fantasy in your head that maybe you can show that you could really do it. And then the reality [sets in]: Say my lines, hit the marks and stop thinking it's actually real."

Most of the driving was done by stuntmen with the second unit, further complicating the inordinate amount of planning required to film those scenes. The climax takes place at Le Mans, where the course is an 8.5-mile loop of roads in the French countryside. However, the track has undergone significant changes in the past 53 years—including the addition of stands, barriers and chicanes—essentially ruling out filming at the venue.

"We didn't want to use CGI except where it was absolutely necessary—putting hundreds of thousands of bodies in the stands, for instance," says production designer François Audouy. "[Mangold] wanted to have a very visceral, immersive experience for the audience." That meant all of the racing was done by real cars on real roads, which required Audouy and Maria Bierniak, the supervising location manager for the second unit, to re-create Le Mans piecemeal. "We learned early on that everyone knows every turn of that track by heart," says Audouy. "And we felt like we really needed to represent those famous sections."

So each lap in the movie involved four locations. The famed Dunlop Bridge was reconstructed at Road Atlanta, a 2.5-mile road course northeast of the city. The Grand Prize raceway in Savannah stood in for the Indianapolis turn and the Esses. The crew constructed the pits and the start/finish line at Agua Dulce Airpark in Southern California.

The trickiest part was finding a site to double as the Mulsanne Straight, a 3.7-mile segment bordered by farms and cow pastures. The filmmakers needed a length of country road that was wide enough for not only the race cars but also for the camera cars and support vehicles. Plus, they had to be able to shut it down for extended periods of time. ("Because, God forbid," says Bierniak, "old Mrs. Johnson decides to back out when you've got a bunch of Ferraris on the road.")

To find their patch of pavement, they relied on good old-fashioned legwork (or pedalwork). Starting in Atlanta, Bierniak and a team of scout drivers went in every direction, hoping to find a little slice of France in Georgia. Even with the help of local departments of transportation and sheriff's offices, they scoured the state for a month before finding their Mulsanne: a stretch of Highway 46 outside Statesboro that they stumbled upon when another recommendation didn't pan out. Says Bierniak, "It was like, Needle? Haystack? Got it. Voilà, it was France!"

Once the locations were locked down, the scenes had to be filmed and stitched together, which was a continuity nightmare. "We have to maintain the dirt level on each car, the light quality," says Mangold. "Is it midday? Is it sunset? Morning? Rain? Is it post-rain with the streets wet? Or raining full on? Are the wipers on?"

The result is a stunning spectacle, fender-banging action that plays out over a gripping third act that, were it not true, would beggar belief.

***

Spending $90 million to make a movie about sports-car racing a half-century ago might seem risky, given the lack of familiar characters and its preponderance of engineers. The project had been kicking around Hollywood for years. At one point, it was positioned as an Ocean's 11-type ensemble with George Clooney and Brad Pitt. At another juncture, Tom Cruise was involved. It got the nudge it needed in early 2018, just before Disney bought 21st Century Fox—thanks to, as Bale explains it, "people wanting to go out with a bang, to make a film that generally doesn't get the kind of funding that we managed to get for this. Something that would make us all proud, a dying breed."

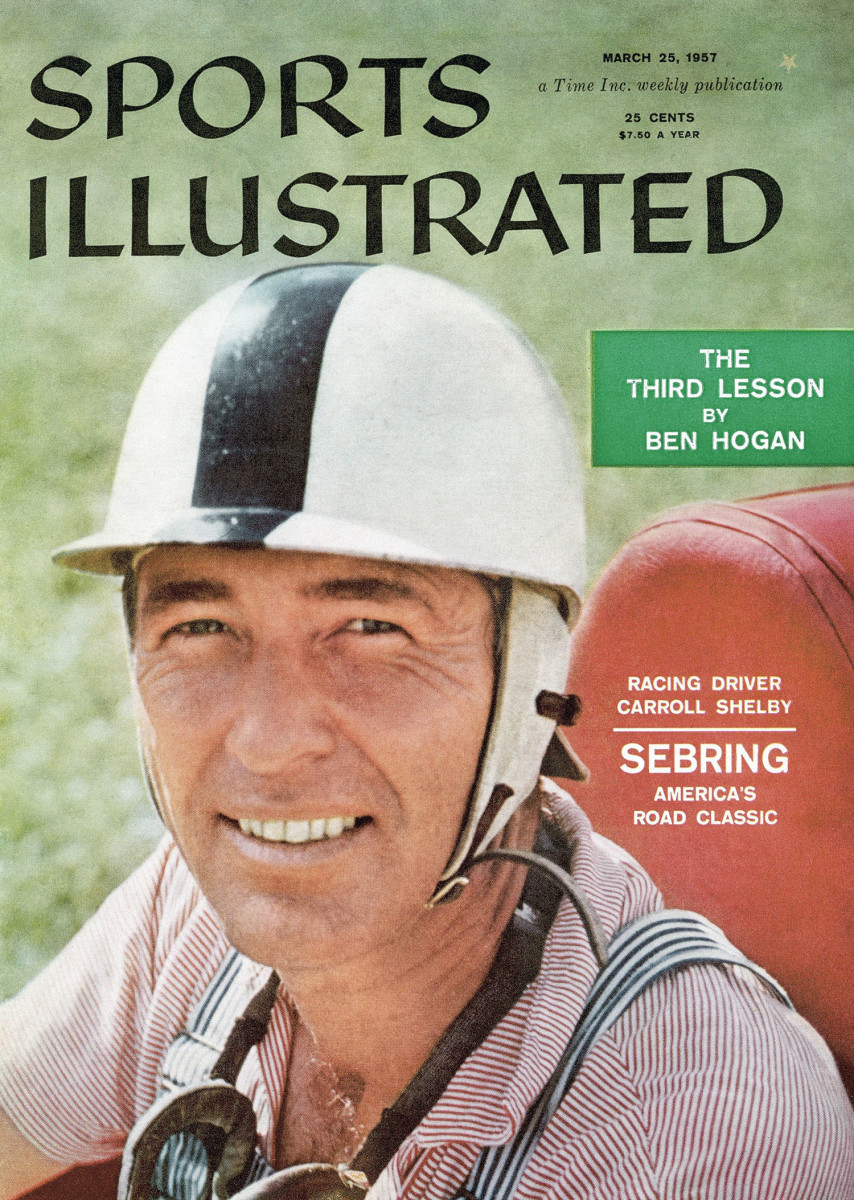

The subject might seem esoteric now, but five or six decades ago, sports-car racing had a mainstream cachet in the U.S. that gave the Ford-Ferrari battle real stakes—credibility, exposure and, by extension, car sales. "The effect of a victory is immediately apparent among our management, our employees, our dealers—and, I'm happy to say, our customers," Henry Ford II told Sports Illustrated in 1966. The Le Mans race that year was broadcast live over two days on ABC, an early hour during the first day and the finish the following morning. Shelby appeared on the cover of this magazine in '57, when he was one of the top drivers in the world, and he was the subject of a 3,500-word SI profile in '65.

The details of his life in those two stories could have provided the grist for a Shelby biopic. The headline of the latter—"Snakes, Butter Beans and Mister Cobra"—only hints at his Texas-sized personality. The son of a rural postman who made his rounds in a 1928 Whippet as Carroll urged him to go faster from the passenger seat, Shelby spent much of his childhood bedridden with what he called "heart leakage." When he returned from Army duty—he had to eat bananas to gain enough weight to serve—he worked as a chicken farmer and an oil roughneck before turning to racing; afterward, he was an African-safari operator and purveyor of his own chili kits.

But that's all squeezed out of the movie. "You really have to pick a focus and stick with it or else you're never going to be able to tell the story in the allotted amount of time," says Damon. So while Miles—a former tank sergeant in the British Army who won 24 Hours of Daytona and 12 Hours of Sebring in '66 before taking on Le Mans—has a wife and son to serve as sounding boards for his hopes and fears, Shelby's off-track life is never explicitly explored. But Mangold and Damon sprinkle in enough well-placed hints to paint enough of a portrait: a mostly-empty whiskey bottle near the bed of his RV, the comfortable way he interacts with the aloof Miles, the unspoken need for his friendship even as they halfheartedly brawl in the street.

Forced to retire because of heart problems shortly after winning Le Mans in 1959 in an Aston Martin (he raced with nitroglycerine pills under his tongue), Shelby began building cars, ultimately teaming with Miles in the early '60s. At that time, the feud between Ford and Ferrari was just beginning. In an era-appropriate moment, Iacocca makes an impassioned case for Ford getting into the sports-car business with a presentation on a Kodak carousel projector, à la Don Draper. "James Bond does not drive a Ford," Iacocca notes.

To which Henry Ford II, played by the excellent Tracy Letts, replies, "That's because James Bond is a degenerate."

Eventually Ford decides to get into racing and pursues a partnership with Enzo Ferrari. A visit to Italy takes a turn when the two sides disagree over how the team would be managed, leading Ferrari to call Ford's cars "ugly" and his physique "fat." Ford responds with a mild ethnic slur, and the race is on, with Shelby recruited and given 90 days to build a car fast enough to win Le Mans. Of course he wants Miles to drive, and of course the buttoned-up execs are having none of it.

There's a familiar trope in auto racing movies of the lead foot who doesn't just go fast—he goes too fast, and if he doesn't watch out his recklessness is going to come back to get him. It surfaces here, as Miles's single-mindedness threatens to undo him in his battles with both Ferrari and Ford. Things come to a head in Le Mans in a way that, had it been dreamed up by a screenwriter, would likely have resulted in calls for a rewrite. But it's true, and it sets up a resolution that's both shocking and completely in line with what the audience has learned about the characters.

There's a scene in the movie that brings to mind the memorable opening of The Right Stuff: "There was a demon that lived in the air," a drawling Levon Helm says in a voice-over. "They said whoever challenged him would die. . . ."

In Ford v Ferrari, another potentially lethal challenge lurks in the ether. It's introduced when Miles takes his son to Shelby's test track near LAX one night. "Out there is the perfect lap. You see it?" he asks in his Brummie accent, jets taking off and coming in overhead.

"I think so," his son replies.

"Most people can't."

It's a simple sentiment, one that reflects the era of the movie and ultimately, to its director, serves as one of the film's enduring messages. "The idea of the perfect lap is a bar he's setting for himself that has nothing to do with winning or losing, but has to do with the quality of his own execution," says Mangold. "And there's something deeply inspiring to me about that way of looking at life, looking at your work. And whatever we do—as a mechanic, as a bus driver—this tremendous pride in the craft of the simplest part of your job, and trying to do it the very best your body and your mind will allow, I think it's something we're missing. I don't want to call it nostalgic, because I hope we can find it again."