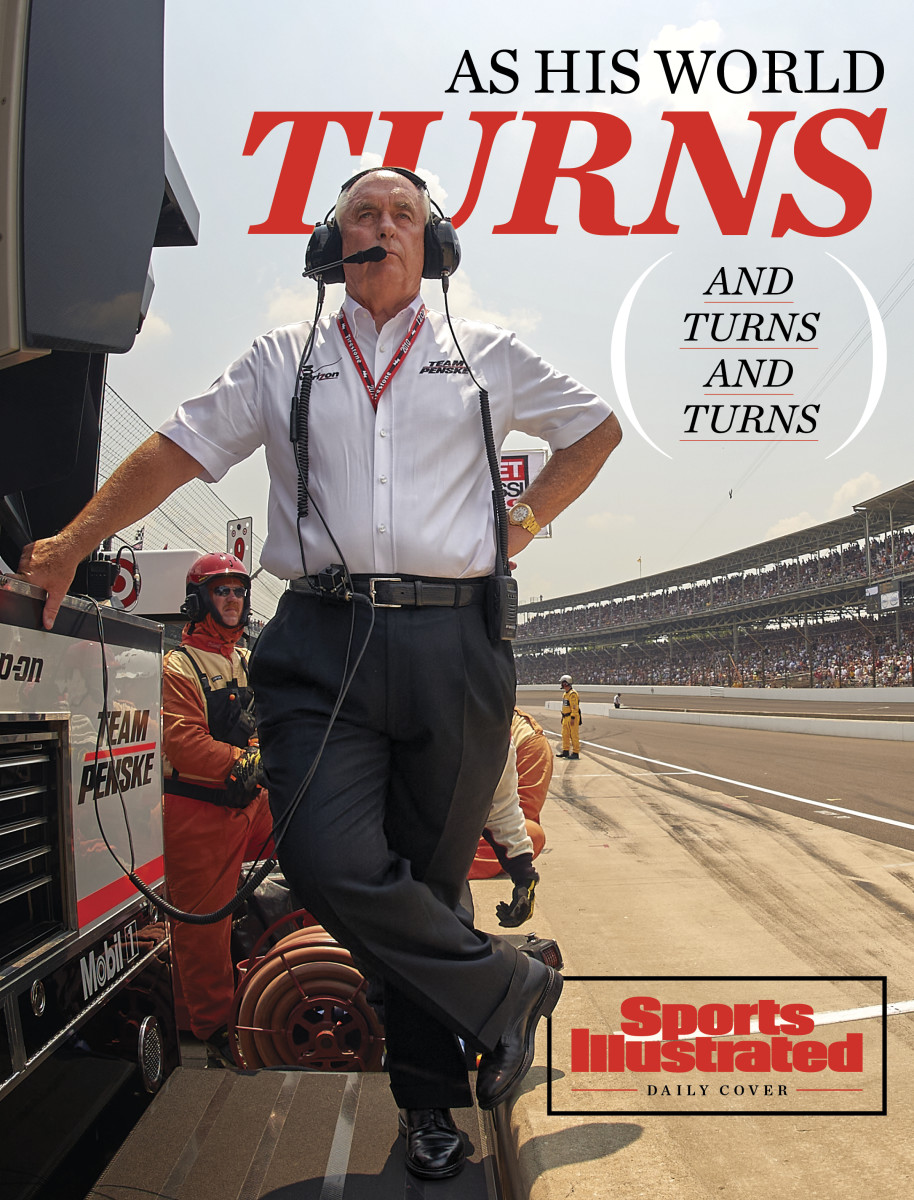

At the Indy 500, Roger Penske Is Still Running Circles Around Everyone

Exactly 70 years ago this Sunday—the day on which the largest U.S. sporting-event crowd since the onset of the pandemic will assemble for the Indianapolis 500—a 14-year-old kid from suburban Cleveland headed west with his father to watch what was then called the 35th International 500-Mile Sweepstakes. Roger Penske and his dad were late arriving at the central Indiana home of the elder Penske’s business associate, for a prerace lunch, and everyone had already left for the track—but before the Penskes headed out they took notice of a show car in the backyard. Roger pulled on a helmet, sat behind the wheel and posed for a photo.

“I’m not so sure that wasn’t the injection of racing at Indianapolis [into my blood], on that afternoon with nobody there,” says the 84-year-old racing legend.

The photograph has been lost to time, but the memories of that day haven’t. “Indianapolis—the ambience, the cars, the chance to go with your dad—was infectious,” says Penske, who in the years since has missed only six 500s (all because of an open-wheel schism in the 1990s). Penske visited first as a fan, then as an owner. His cars have won the race 18 times, many of those in the event’s ’70s and ’80s heyday, when prime-time TV coverage drew massive audiences and the event dominated discussion in the sports universe.

This year Penske will be at Indy in yet another capacity: track owner. If Yankee Stadium, made possible by the unprecedented exploits of the larger-than-life Bambino, was the House That Ruth Built, then consider the 112-year-old Brickyard, lifted into the spotlight year and year again by Penske’s envelope-pushing hotfoots, the House That Roger Is Rebuilding.

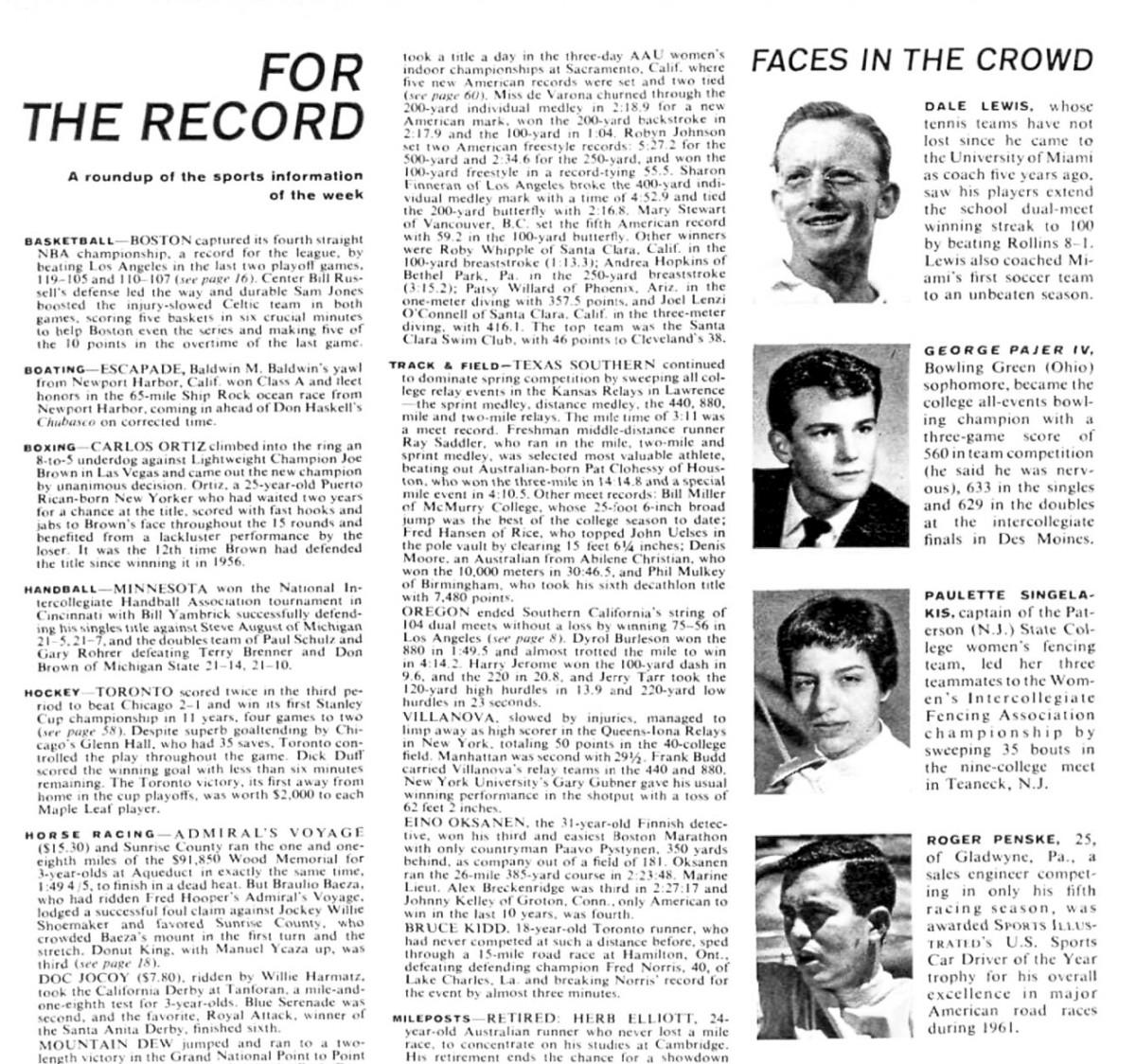

One thing Penske hasn’t done in Indianapolis is drive, but that’s not to say he couldn’t have. He got his start behind the wheel doing hill climbs in the late 1950s, when he was a student at Lehigh, and by the early ’60s he’d become one of the best road racers in the country, if not the world, routinely beating the likes of Dan Gurney and Parnelli Jones. In April 1962 he appeared in Sports Illustrated’s Faces in the Crowd, having been named a year earlier as the magazine’s U.S. Sports Car Driver of the Year. A year later he was the subject of a 6,000-word feature in the magazine.

In the piece, Penske, then 26, spouted a bunch of truisms, like “Nothing is impossible” and “You never get anywhere unless you do something.” But he also demonstrated a pragmatism rarely seen in drivers, then or now. He was no hotshot adrenaline junkie. He was a graduate of Lehigh with a degree in industrial management—though he admitted “I never studied.” Still, he was cerebral, with an eye always on the big picture. “It lurks in my mind: Use your head and not your foot,” he said, pointing out that his objective was to win at the slowest speed possible. (This wisdom was not lost on other drivers. After Penske finished ninth in the 1962 United States Grand Prix, one of two Formula One races he competed in, he received a note from the venerable English driver Stirling Moss: “It’s none of my business, but I wanted to tell you that I thought you drove a damn good race. Intelligence is a rare ability. ... P.S. My first fan letter for years.”)

At the time, Penske was really just moonlighting as a driver. During the week he sold aluminum for Alcoa, a job he probably could have given up but didn’t want to. “I’m trying to maintain an image as a businessman, a responsible person,” he said back then. “Racing, in this sense, is hurting me. I don’t want to be known as a race driver. I’ll be selling aluminum long after I’m through racing.”

His future, it turned out, didn’t lie in aluminum—but he wasn’t quite off to the races yet, either. He took a job at a car dealership in 1963 and two years later had a chance to take over a Chevrolet dealership in Philadelphia, with the catch that Chevy didn’t want him racing, too. So when Clint Brawner offered him a chance to test a car at Indy in ’65, Penske said no. (Brawner then offered the seat to another up-and-comer, a kid named Mario Andretti, who finished third a few months later in his Brickyard debut and went on to have a decent career.)

It wasn’t the first time Penske turned down a chance to drive at Indy, a track he deemed too dangerous. “There’s so much I want to do,” he said in 1963, “and I want to be around to do it.” Instead, he stopped driving, threw himself into his dealership and before long started a race team. He just needed a driver, and in 1966 he found his man.

If Penske had a kindred spirit in racing it was Mark Donohue, another almost-30-year-old, who held a degree in mechanical engineering from Brown. In a sport where elbow grease and intuition were the most valued tools, they stood out with their spotless equipment and embrace of data. “They used to call us ‘the college boys,’ with our polished wheels and crew haircuts,” says Penske. “Well, now everybody’s got polished wheels and crew cuts. It was just a revolutionary change.”

Their first race together nearly ended in disaster when Donohue’s car collided with another vehicle at full speed and burst into flames, sending him to the hospital with first- and second-degree burns. Donohue recovered, though, and soon he and Penske were dominating the scene. They made their Brickyard debut in 1969, embracing their reputation as—in SI’s words—“the slide rule boys,” with a sign hanging in their garage that read: THOSE OF YOU WHO THINK YOU KNOW IT ALL ARE PARTICULARLY ANNOYING TO THOSE OF US WHO DO.

They debuted at the Indy 500 Winner’s Circle in 1972 after setting a race-record average speed of 162.962 mph that stood for 12 years. “The first one always stands out the most because that’s the toughest one to get,” says Penske—but the victory remains sentimental for another reason, too. Three years later he mourned the loss of his friend when Donohue was killed in practice before the Austrian Grand Prix.

There would be more Indy wins to come, but not for seven years, when a different kind of driver made his mark on the Brickyard. Rick Mears wasn’t the crewcut type. He was a Californian through and through, one of the best off-road racers around. “He had long hair, he had a leather hat, and I saw him pushing this pink Eagle [car] up and down the pit lane,” recalls Penske, who gave Mears a seat in 1978. The following year they won their first of four 500s.

“In ’91 [in Indy] we had a wheel come off on Friday afternoon—I didn’t have it on tight,” says Penske. “He hit, he rolled over down between [turns] one and two, and they took him to the hospital. He came back; he could hardly walk. He said, ‘I want to get the backup car.’ Got in the backup car, turned the fastest lap of the month. The next day, he sat on the pole. And a week later he won the race. That’s Rick Mears.”

Penske’s winning cars have ranged from a year-old vehicle that was literally pulled out of a hotel lobby to a car featuring an engine so cutting-edge that it was immediately outlawed. In 1987, driver Danny Ongais crashed one of Penske’s new cars in practice. The wreck raised two problems: 1) Ongais was concussed and couldn’t race. 2) The new car clearly wasn’t up to snuff. To address the former, Penske hired Al Unser, a three-time winner who didn’t have a seat. To address the latter, he decided to use an ’86 chassis. A search was undertaken and one was tracked down on a show car in the lobby of a Sheraton Inn in Reading, Pa. His team got the car to Indy, where Unser qualified 20th and went on to win the race.

At the other end of the spectrum was the car that Unser’s son, Al Jr., took to victory lane seven years later. At the time, the rule book contained a gaping loophole. For years, the Indianapolis 500 was sanctioned by the United States Auto Club, which ran a full-season open-wheel schedule. The race itself was operated by the Hulman family, whose patriarch, Tony, bought the track in 1945 after it had sat dormant for four years during World War II. Then, in 1979, Penske and several other team owners started Championship Auto Racing Teams, which put on its own open-wheel slate but still competed at Indy. That set up an awkward situation in which teams used CART regulations everywhere except Indy, where USAC’s guidelines ruled.

This was considered by most to be a moot point; no one expected a team to shell out the money to build an entirely different machine for this one race. But Penske did just that. He teamed with Ilmor, a British engineering company, to build a more powerful (one-time-use) engine than CART’s rules would allow, but that was within USAC’s limits. The top-secret work was done in England, with engineers shuttling parts across the ocean on the Concorde. The results were astounding: Penske’s cars had an advantage of about 150 horsepower—roughly 5 mph on the straightaways—over the field. “We sat on the pole and led every lap,” Penske says. “It took them about two weeks to change the rules.”

The controversy underscored a question of growing importance in open-wheel racing at the time: Who’s wielding the power? Tony George, Tony Hulman’s grandson, was the chairman of the speedway and wanted more of a say in the direction of the sport. He favored racing only on ovals (eliminating road courses and temporary street circuits), which he thought would increase interest by drawing more U.S. drivers and decrease costs that he believed were spiraling out of control. CART gave him a seat on the board, but only a nonvoting one, which in 1994 led him, fed up, to announce that he was starting his own league—and that 25 of Indy’s 33 spots would be allocated to it.

CART refused to buckle, so on Memorial Day weekend of 1996, Penske found himself not in Indianapolis but at Michigan International Speedway, where the “jewel” in CART’s schedule was held on the same afternoon as the Indy 500 in front of a wildly indifferent audience, much of which had been lured to the track by free tickets. “Looking back, it was probably one of the dumber decisions I made in racing,” says Penske. “We didn’t realize the history and the prestige of racing at Indianapolis, that there was nothing we could do that would ever equal it. So in 2001 we decided we were coming back. … We looked at it and said, ‘We’re not going anywhere without Indianapolis.’ ”

Upon his return, Penske won with Helio Castroneves, declaring at the time: “It’s the best day of my life, redeeming myself like this.” The pair won again in 2002, and Penske teammate Gil de Ferran made it a three-peat in ’03.

The damage, though, had been done. Like most sports outside of football, open-wheel racing has struggled to maintain its audience in the 21st century. By the fall of 2019, George and his family decided it was time to cash out. That September, four months after Simon Pagenaud gave Penske his 18th Indy win, George and his CEO, Mark Miles, approached Penske at Laguna Seca Raceway to see if he had any interest in buying not just the track but the entire IndyCar series. It was all very hush-hush, but they let Penske know they had other irons in the fire and would need to know soon whether he was interested. Within a week they had a verbal agreement.

Before the deal even closed, Penske started taking long walks around the Indianapolis property, looking for ways to improve it. “We knew the track itself, the road course, the garage area—we lived in that for years,” he says. “Nothing there was going to blindside us.”

The rest of it, though, was eye-opening.

At this point, it becomes necessary to talk about urinal troughs. For years, visiting the lavatory at Indy was like going to the loo in an especially Dickensian 19th-century pub. The cinder block rooms were cramped and largely unpainted; in the men’s versions, the defining features were the long, decrepit, wall-mounted troughs that looked like they predated young Roger’s first visit, in 1951. The less said about the smell, the better.

For some reason, though, the troughs had a certain cachet. Visiting the facilities was something of a rite of passage for young Hoosier lads. The Speedway even sells urinal trough T-shirts on its website.

“There are stories that are now legend about how much time he and I spent in restrooms,” says Miles, who remained in his position after Penske took over. “Thinking: How do you paint these cinder block buildings that have never been painted? Where would the LED lights go? Would we change from paper towels to air hand dryers? I’m sure I’ve been in the same restroom with him 25 times.”

In a way, the bathrooms summarized what Penske was—and is still—up against: trying to attract new fans without alienating the existing, trough-loving base. (Penske’s toilet solution: lots of paint, and shiny new troughs.)

Ultimately, he went over every inch of the property, and he hasn’t been afraid to try anything. Miles remembers walking through the stands with Penske two winters ago when someone suggested replacing infield grandstands with ground-level suites. Penske replied: “Let’s do it. Let’s go ahead and build one; knock out those seats and see if we like it.” (“His general counsel was in the group with us,” Miles recalls. “He tugs me on the elbow and says, ‘He forgot he doesn’t own it yet.’ ”)

Penske’s attention to detail is notable, not just because those grounds he walked countless times are huge and he is in his 80s. The Speedway, as near and dear as it is to heart, makes up but a tiny piece of his business empire, which includes race teams, car dealerships and a truck rental company. He employs more than 55,000 people worldwide and Forbes estimates his worth at $2.4 billion. “We are a small part of his business,” says Miles. “But I get a lot more mindshare of Roger than we represent economically.”

Which should give you some idea of how much Penske was looking forward to last year’s Indy 500, the first chance to show off his crown jewel. The deal closed in January 2020 … and then two months later everything was turned upside down. The 500 was postponed and ultimately held in August, to a largely empty track.

Penske remained stoic and, as always, pragmatic. “Quite honestly,” he says, “we haven’t spent much time feeling sorry for ourselves. There’s an opportunity in everything. We’ve been able to do more [work on improvements] with the downtime. And—I think more important—during that time we really tried to get connected with the community.”

The Brickyard hosted the high school graduation ceremony for the town of Speedway (the Indianapolis enclave that is home to the track), plus a funeral service for a police officer killed in the line of duty, as well as COVID-19 testing and vaccinations. “Those things were more important than having the race,” says Penske. “We’re the anchor for the community. And during COVID, they needed us more than ever. It was well worth it, and it wasn’t a challenge—it was a duty, one that someone told me that I needed to do. And I guess that might’ve been my mom and dad saying to me, Give something back.”

And so now, a year later, he’ll finally get to welcome a crowd: 135,000 are expected for the race on Sunday. (Miles says that 90% of the paddock has been vaccinated, and based on demographic data of ticket buyers he believes that about half of the people in the stands will have received vaccinations.) Penske has four cars in the field, and he’ll also be keeping an eye on the Paretta Autosport team, an almost all-women outfit, including driver Simona De Silvestro, that is supported by a technical partnership with Penske. However, now that he’s running the league he’s scaled back his race day duties; he’s no longer on the pit box. “That’s the worst part of the deal,” he says. “I used to be carrying the golf bag, now I’ve got to stand outside the ropes.”

But he doesn’t sound like a man who’s not at peace with the situation. Reflecting on qualifying and practice sessions at the track last week, he marveled at the crowd noise, at the parents who’d taken their kids to the Brickyard as his own dad did seven decades ago.

“We’ve waited for it,” he says. “It was worth every day. And more.”

• The First U.S. Car Race Was Won 125 Years Ago ... At 7 mph

• The Mental Peril of This NBA Season

• Police Killed George Floyd. An MMA Fighter Punched Back