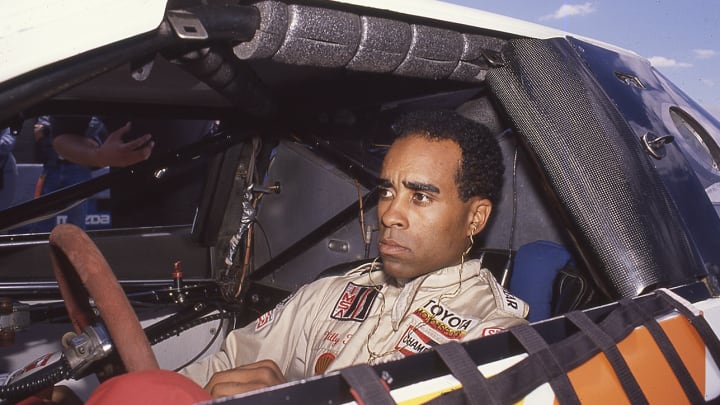

Willy T. Ribbs Is Racing’s Original Barrier-Breaker

213.189 mph: That’s the mark Willy T. Ribbs needed to beat to become the first Black man to qualify for the Indianapolis 500.

It was 1991 and Ribbs’s last attempt after several trying weeks on a tight $350,000 budget. He ended up blowing three engines, leaving the crew without a motor as they came down to the wire. Another team also had a Buick engine, and while many pleaded with the car manufacturer to step in, a representative, at first, said it wouldn’t intervene. But by “bump day,” the last chance to qualify for the Indy 500, Ribbs and Walker Racing had an engine.

Only 33 cars could qualify for one of motor sports’ biggest races, and that morning, smoke billowed from Ribbs’s car, threatening his chances. Up until that afternoon, speed had evaded him, and he hadn’t cracked 210 mph on the track.

For Ribbs, it was not a matter of whether he would succeed in motorsports. It was a must. His grandfather used to tell him and his cousin as they worked on their grandfather’s ranch, “You boys got one strike right now against you,” Ribbs recalls, adding that he never looked at them when he said this. His grandfather went on to ask, “You know what that strike is?”

“You were born Black. That’s one strike.”

That conversation with his grandfather shaped how Ribbs approached life and motor sports. Born in 1955, the California native was raised in the latter part of the Jim Crow era, during which the remaining laws from that time were not overturned until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. His grandfather built a successful plumbing business from the ground up, so successful that Ribbs’s father could pursue racing as a hobby. Ribbs knew as early as 9 years old that he didn’t want to manage the family business, setting his eyes on the track despite the obstacles ahead.

He spent his teenage years on his grandfather’s 300-acre ranch, and at as young as 13 years old, Ribbs drove cars along the mountain roads on the property, learning car control, among other skills. By 21, he entered racing school, and following his high school graduation, Ribbs skipped over to Europe. Early in his career, he dominated in Formula Ford with Mike Eastick’s Scorpion Racing School and competed against eventual Formula One legend Nigel Mansell. Though Ribbs was successful, he ran out of money and had to move back to the U.S., eventually competing in Formula Atlantic before Charlotte Motor Speedway president and race promoter Humpy Wheeler tapped him to drive a car in NASCAR’s Winston Cup at the World 600 in 1978. But as Ribbs described in his documentary, Uppity, there was animosity when he came back Stateside.

No drivers spoke to him during the drivers’ meeting at Long Beach in Formula Atlantic, and come time for NASCAR, the death threats got so significant that they pulled the plug on him competing.

“NASCAR knew that it would have been pushing the envelope for me to be there,” Ribbs says. “The other drivers—Lewis [Hamilton] is a very nice guy. He's a gentleman. He’s a very nice person, and he has taken a lot of abuse. Willy T. Ribbs is just not wired that way. My grandpa would have kicked my ass for taking the abuse.

“I think it was clear that there was going to be … some controversy because I wasn’t going to take any crap from any of them. And they knew it. NASCAR could have controlled that negative side if they wanted to, but they didn’t.”

Ribbs kept his eyes on the Indy 500 and F1, his ultimate goals in his motor sport career. His first shot at Indianapolis came in 1985; however, he was forced to withdraw. Ribbs felt there was someone on the team who didn’t want him there: Paul Leffler, his head mechanic. He said in Uppity, “It felt eerie dealing with the guy, like he was an executioner.”

The dangers are higher at Indy with drivers dying from wrecks at high speeds. One small mistake can send someone into the wall. Ribbs recounted how when he was fitted in the car, he was sitting too high, which would’ve forced his head to move around almost like a bobblehead. Feeling “helpless,” Ribbs withdrew.

But he never gave up on his dreams. Growing up, Ribbs’s driver heroes were the likes of Jim Clark, Dan Gurney, Graham Hill and Juan Manuel Fangio and the reasons “why I wanted to be a Formula One driver.” Bernie Ecclestone, the now former Formula One CEO, gave Ribbs his first chance—a test drive with the Brabham team, making him the first Black driver to test an F1 car.

Driving a car like that “was like going on another planet,” Ribbs says. He adds, “When cars are that sophisticated, they’re going to be very fast. But they’re so sophisticated that that speed is not overwhelming. … My biggest adjustment to drive in something like that was to be able to trust and being able to trust that the car will do what the numbers say it will do.” While you may hit the brakes before a turn a football-field length away, Ribbs says, in an F1 car, you’re pressing the brakes at the 20-yard line.

”It’s mind boggling how the car will go from 200 miles per hour down to 50. And you have to convince yourself you know how to do it,” he says.

However, the opportunity did not amount to a seat on the grid or as a reserve role. Rather, he later returned to the sport as an ambassador. Ribbs may have been viewed as jumping from series to series, but he eventually found backing in Bill Cosby, the controversial comedian widely known as “America’s Dad” who’s been accused by at least 60 women of sexual misconduct dating back to the 1960s.

Ribbs says while Cosby “was not interested in racing,” he did see what Ribbs faced, eventually calling the driver to offer his help and asking where Ribbs wanted to race. He set his sights on IndyCar because F1 had a “military budget.”

“The hostility in IndyCar was nothing like NASCAR. … They weren’t hostile like NASCAR was hostile,” Ribbs says. “But they were silent, and silence is complicity.”

With Cosby’s backing, Ribbs set out in his final attempt to qualify for the 1991 Indy 500. He nailed that first corner, finding speed that eluded him in previous runs. The first lap was just over 217 mph. Ribbs placed his left foot on top of his right and floored it.

And it worked.

Arms were flying; cheers echoed as Ribbs crossed the finish line. Teams flooded the pit road to congratulate him on making history. Come race day, his car lasted only five laps before the engine gave out, but Ribbs returned again in 1993 with a sponsor in Service Merchandise, thanks to Cosby and the William Morris Agency of Beverly Hills.

“It shouldn’t have been any tougher for me than anyone else,” Ribbs says, reflecting on his career. “It should be a level playing field. And it wasn’t, and it was designed not to be level.”

Fast forward to 2023; some progress has been made—to an extent. There’s only one Black driver racing in Formula One (Lewis Hamilton), one full-time driver in the NASCAR Cup Series (Bubba Wallace) and none in IndyCar.

“The biggest disappointment is that IndyCar racing and the Indy 500 only had two Black drivers in history—two,” Ribbs says. “What is the message? Formula One, their message is you can be like Lewis, right? This is the greatest Formula One driver ever. He’s a Black driver. He’s the winningest when it comes to all the numbers. No one has done more than Lewis Hamilton, and Formula One loves it.”