Throwback Thursday: The USA's captivating 1994 World Cup group showing

BY ALEXANDER WOLFF

With the World Cup just mere weeks away there's no better time to look back in the annals of U.S. Soccer to recall past teams and their experience on the world stage. Every Thursday from now until the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, we'll dig into the SI Vault for a Throwback Thursday adventure, sifting through the USA's history as the Americans look to create a new chapter this summer.

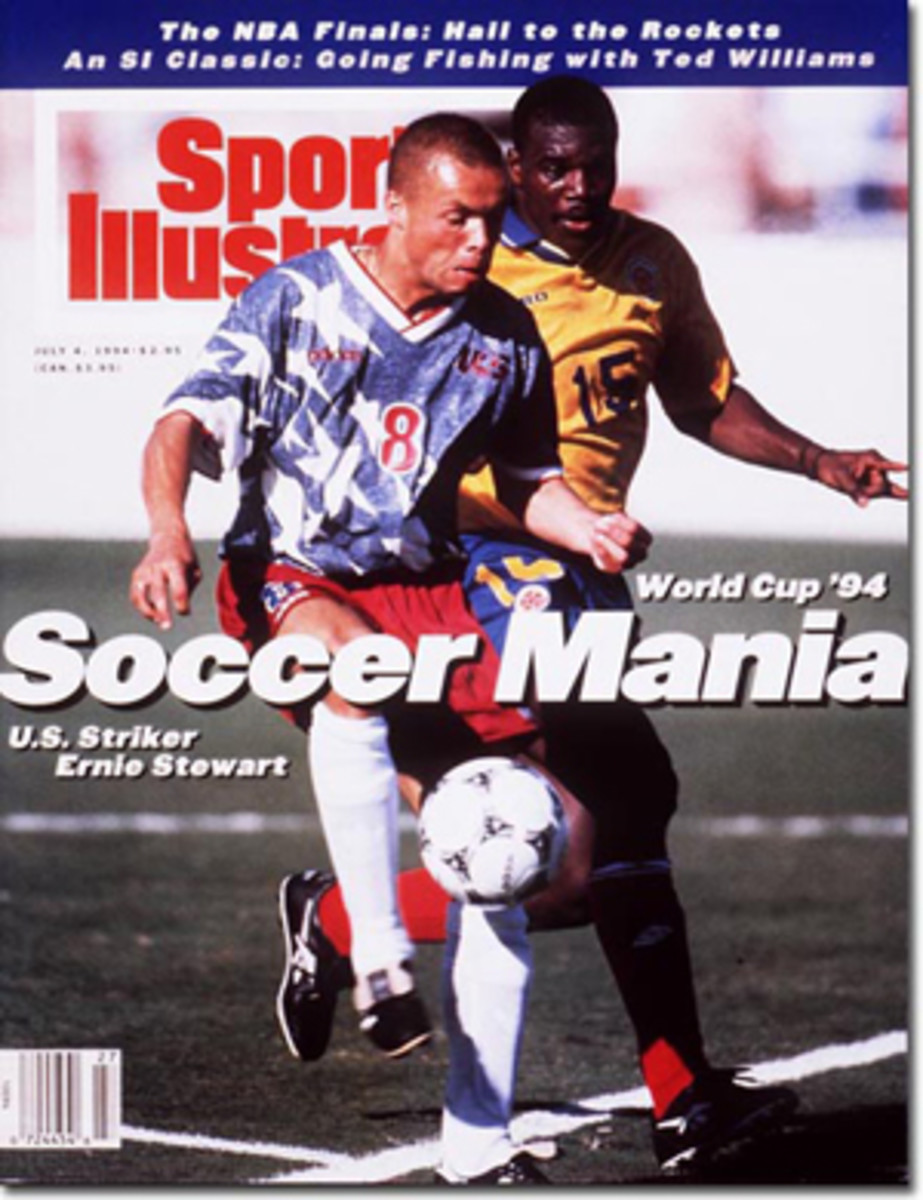

Our first look back: Wolff's SI Magazine cover story from the July 4, 1994, issue, chronicling host USA's 1994 World Cup group-stage experience, including the 2-1 triumph over heavily favored Colombia:

1994 U.S. national team manager Bora Milutinovic salutes the crowd at the Rose Bowl after a landmark win over Colombia. (David Cannon/Getty Images)

Good thing that bicycle kick missed. Had it not—had U.S. defender Marcelo Balboa's blind, backward-somersaulting, ridiculously improbable shot late in America's 2-1 World Cup defeat of Colombia on June 22 actually found the back of the net instead of sailing wide left by inches—the entire country might have died a soccer death, stricken by over-excitement. Every videotape machine might have wheezed its last, replaying for the thousandth time what Pelé called "the most beautiful moment of the World Cup so far."

With its millennial victory in the Rose Bowl over a Colombian squad that had been the trendy choice to win the Cup, the home team not only brought the phrase "American soccer" out of the realm of oxymoron but also introduced a clutch of apparent contradictions. In spite of Sunday's 1-0 loss to Romania in Pasadena, the defeat of Colombia virtually assured the U.S. a spot in the second round when it gets under way this week, so get used to hearing about the "ponytailed barber's son." And the "37-year-old blur." And the "popular Serb."

Not a week earlier the international consensus was simple: The U.S. wouldn't have been in the World Cup at all if the host country didn't get an automatic berth. Now, suddenly, headline writers were calling the victory a MIRACLE ON GRASS, although no one on the American team wanted any part of that characterization. "A miracle is when a baby survives a plane crash," said Alexi Lalas, the U.S. defender who looks like the love child of Rasputin and Phyllis Oilier. Added Bora Milutinovic, the Yugoslav coach of the American team, in his pidgin Spanglish, "It is nor-mal."

When Alan Rothenberg, the chairman of World Cup USA 1994 and the president of U.S. Soccer, declared a few months ago that the American team was "a lead-pipe cinch" to reach the second round, he wasn't putting any additional pressure on the U.S. players. There was plenty of pressure already, for the players agreed that failure to go through to the round of 16 would make this World Cup a disaster for American soccer. Rather, Rothenberg was declaring his faith in Milutinovic's ability to work quadrennial magic. In 1986 Milutinovic guided Mexico to a surprising spot in the quarterfinals. Four years later he took tiny Costa Rica into the second round. Small wonder the U.S. federation took the advice of former German coach and superstar Franz Beckenbauer and hired Milutinovic in '91.

No one knows quite how Milutinovic does it. One of his favorite words, tranquilo, summarizes well the confidence and calm he tries to impart to his players. His obsession with assembling 22 men who are content in their roles led him to cut the captain of the Costa Rican team, and it figured in his surprising decision to let veteran U.S. sweeper Desmond Armstrong go this spring. Mystical and inscrutable, a man who communicates with indirection and shoulder shrugs, Milutinovic is obsessively secretive about matters of strategy. "You are first-timer!" he cackled last Friday at a green reporter who foolishly asked him how the U.S. would approach its game with Romania. "Nobody can figure him out," says U.S. midfielder Hugo Perez. "I can only tell you he knows what he's doing."

Soccer isn't a literal game but one of hunches and feelings and instinct. So perhaps fluency in English would be a skill wasted on a witch doctor like Milutinovic. Throughout the run-up to the Cup he served as a lightning rod not only for the growing skepticism about his team's chances but also for his players' anxieties. This allowed them to develop a self-confidence out of all proportion to their international reputation and, probably, their ability. "With Bora, everything is possible," says U.S. assistant coach Steve Sampson. Indeed, every lineup is possible, every tactic—and, ultimately, every result.

In World Cup tune-ups barely two months ago, the Americans tied Moldova and lost to Chile and Iceland. The defense was suspect, the offense absent. Still, Milutinovic kept incanting his mantra: So long as you learn from every tie, from every loss, all that matters is the World Cup, the World Cup. As U.S. defender Fernando Clavijo said to reporters after the victory over Colombia, "Do you remember we lost to Iceland now?"

U.S. defender, and current ESPN analyst, Alexi Lalas became a cult hero of sorts following the 1994 World Cup (Patrick Hertzog/AFP/Getty Images)

Still, there was no accounting for how the Americans would respond to the pressure of being hosts of the world's greatest single-sport event. Some of the European veterans on the U.S. squad—John Harkes, who plays in England; Eric Wynalda, who plays in Germany; and Tab Ramos, who plays in Spain—sensed that uncertainty in the silence during the bus ride to the Rose Bowl for the game against Colombia. "Hey, guys, this is what pressure feels like," Wynalda said. "Doesn't it feel good? Enjoy it."

Meanwhile, Milutinovic was doing his part, tossing a pinch of this, a pinch of that into the brew. On apparent whim he benched burly defender Cle Kooiman in favor of the oldest American player, the 37-year-old Clavijo. Though Clavijo hadn't seen game action in months. Milutinovic may have gone to him because Clavijo is one of the team's three fastest players and because Milutinovic trusted Clavijo's feel for the Latin game.

"Another Bora mystery" is how midfielder Mike Sorber described his own inclusion in the U.S. lineup. For a while Sorber had doubted he would even make the final roster. But since Claudio Reyna, the Americans' 20-year-old phenom, tore a hamstring on June 8, Sorber had stepped in and played steadily at midfield with the more adventurous Tom Dooley.

Early in the game against Colombia both Clavijo and Sorber figured in a sequence that augured well for the afternoon. Colombia's Herman Gaviria fired a shot toward the U.S. net that caromed off Sorber's chest, against the left goalpost, then back out to another Colombian player, Antony de Avila, who struck the ball again. This time it ricocheted off Sorber's foot and rolled in front of the goalmouth, where it stayed until Clavijo cleared it.

U.S. midfielder Roy Wegerle would call that escape "our little slice of luck." But the U.S. was served up another slice a few minutes later when Harkes sent in a cross from the left wing, hoping forward Ernie Stewart could run onto it. Stewart couldn't, largely because Colombian defender Andres Escobar, sticking his leg backward in an instinctive attempt to clear the ball, instead sent it past goalkeeper Oscar Cordoba and into the net. For all the American obsession with the late Colombian cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar, this was an ironic turn of events: Escobar's dead: long live Escobar!

Meanwhile, from watching Colombia struggle through a 3-1 opening-game loss to Romania. Milutinovic had drawn a lesson. The Colombians love to make short, fastidious passes, particularly up the gut of the field. So the U.S. defense conceded the wings. Lalas, Balboa, Clavijo and Paul Caligiuri instead clogged the middle, where they could take advantage of their superior height and strength. This tactic so bamboozled Faustino Asprilla, Colombia's star striker, that coach Francisco Maturana benched him at halftime. "I don't think we could have played so poorly even on purpose," said Maturana, who would resign several days later.

FAR POST: Colombia's indomitable Faustino Asprilla

To be sure, Colombia had its excuses. A fax to the team's hotel in Fullerton, Calif., on the eve of the game, threatening the homes, families and persons of both Maturana and midfielder Gabriel Gomez if Gomez played, certainly left the Colombians out of sorts. "And the football coach at Ohio State talks about "distractions!' " huffed the man from the International Herald Tribune.

But the U.S. could point to plenty that it did right too. Stewart would score the game-winner in the second half, taking a chipped lead pass from Ramos and beating Cordoba. Colombia wouldn't get the better of U.S. goalkeeper Tony Meola, he of the equine tresses and coiffeur dad, until the final minute, but by then nothing could forestall the gathering celebration. When the referee blew his whistle, the U.S. players donned American flags like capes and made the rounds of the Rose Bowl as if they were so many Clark Rents just emerged from years in a phone booth. "Making soccer history—that's what we're here for," said Harkes.

Citing pretournament price-gouging and ticket snafus, some soccer insiders had begun to take the World Cup USA '94's ambitious slogan and throw the accent on the last word—"Making soccer history," as in finished, over, done with. The cynics weren't being heard from now. All signs last week pointed to a Cup runneth over. Through Sunday, attendance in the nine venue cities for the first round averaged 96% of capacity. TV ratings have been astonishing for a spectator sport supposedly less popular than tractor-pulling: ABC's telecast of the Americans' opener against Switzerland whupped U.S. Open golf; the cablecast of the U.S. versus Colombia outdrew every baseball game that ESPN had carried this season: and the U.S.-Romania game won its time period, according to the overnight ratings. Meanwhile, bookies in London shortened the odds against the Americans' winning soccer's greatest prize from 100-to-1 to 33-to-1. All very heady stuff for a nation whose history in the World Cup to this point has been so brief as to be, literally, trivial:

Q. What was the Americans' most memorable moment during their 6-1 semifinal loss to Argentina in the first Cup, in 1930?

A. It came when the U.S. trainer rushed onto the field to protest a referee's call, dropped his first-aid kit, smashed a bottle of chloroform and passed out.

Q. Whatever became of Joe Gaetjens, the forward whose header accounted for the Americans' stunning 1-0 upset of England in 1950?

A. No one knows for sure, though it's believed he went back to his native Haiti and was murdered by the Tontons Macoutes.

Q. What did Bill Jeffrey, coach of the 1950 team, say following that game with England?

A. "This is all that's needed to make the game go in the States."

The 1994 denim jerseys. Oh, the jerseys. (Bob Thomas/Getty Images)

Even the Yanks' cameo in the World Cup in Italy four years ago barely merits an entry in the sport's annals. The Americans played punt-on-third-down soccer, lost three straight games and got dismissed as college boys. Thus it was particularly sweet for Meola to watch the U.S. play keepaway against Colombia as the final seconds ticked down. "For so many years people were doing that to us," he said. "And here we are, playing a team picked to win the final, and we're doing it to them."

Unfortunately for the Americans, Sunday's loss to Romania meant a probable second-round match on July 4 with one of the world's soccer powers, Brazil, in the single-elimination phase of the tournament. One loss ends the party. Even so, the enthusiasm generated by the win over Colombia figures to have a long-lasting effect in the U.S.

Soccer Stateside has been derided in the past as the world's biggest baby-sitting service, but last week this huge youth-participant sport came of age. In the dressing room before the U.S.-Colombia game, the man who had done more than any other to pull American soccer into adulthood, conceding his own linguistic shortcomings, asked Sampson to put some English-language wisdom up on the team's blackboard to stir the troops. Sampson wrote SEIZE THE MOMENT in large letters.

"I don't know what is—but is good," Milutinovic would say of Sampson's choice. Still, the coach was curious. "What is this 'size the moment?' "

Muy grande