Three center back alignment a prevailing World Cup tactical trend

The most interesting tactical trend at the 2014 World Cup has been an increase in nations using systems with three center backs. Teams starting matches with these systems have won 11 matches, lost three and drawn four, and all three of the losses were against teams using a similar system.

Formations are relative and just convenient notation for players’ starting positions, so the numerical ways of describing these systems are numerous: 3-5-2, 5-3-2, 3-4-3, 5-4-1. The common denominators are three central defenders good in 1-on-1 situations, usually a ball-winning anchor and two man-markers, and wingbacks that track the distance of the touchline to provide both cover and pressure.

The re-emergence of three-back systems may have been a direct response to the tiki-taka trend sparked in Spain nearly a decade ago. The Spanish system favors central overloads by the midfielders, a false No. 9 and central wingers, leaving fullbacks to provide width in attack. Systems with just two or three central midfielders end up overwhelmed, but playing one less in the back allows for an extra in midfield.

After a certain point, a central overload becomes stifling. A 5-on-2 situation is conducive to keeping the ball in tight spaces, but 5-on-5 means passing lanes disappear. That’s how the Netherlands beat Spain 5-1 in their rematch of the 2010 final to open Group B play.

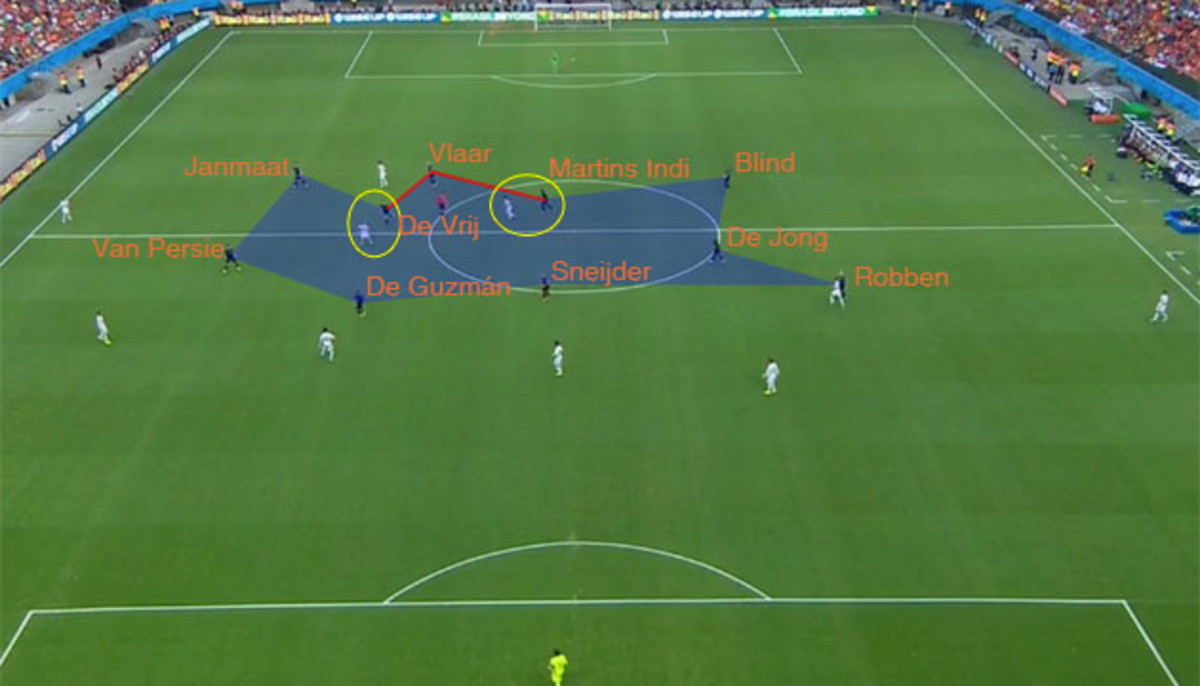

Stefan De Vrij and Bruno Martins Indi played the man-marker roles, tracking runners into midfield, while Jonathan De Guzmán and Nigel De Jong acted as destroyers in holding roles. The wingbacks recovered and pinched in to maintain a solid back line when De Vrij and Martins Indi tracked runners, and Spain couldn’t establish a rhythm in possession.

Upon regaining possession, the wingbacks bombed forward, exploiting space created by the opposition’s overlapping fullbacks. Daley Blind turned in a Man of the Match performance with two assists.

The Dutch struggled against Australia for the same reason they succeeded in the first match: their 5-3-2 is set up to counterattack, which provided the perfect antidote to Spain’s system, but it didn’t help the Oranje push the tempo against an inferior Australian side. Louis van Gaal moved to 4-3-3 in the second half to secure the victory after allowing Australia to control the tempo and expend energy in the first.

Louis van Gaal's methods make the Dutch World Cup contenders again

Similarly, van Gaal moved to 4-3-3 after Mexico took a 1-0 lead in their round of 16 match on Sunday. Again, the system switch provided numbers in attack, and, along with the timely introduction of Klaas-Jan Huntelaar for Robin van Persie, was the difference in winning on two late goals. Against Mexico and Australia were the only matches in which the Oranje possessed the ball more than 50 percent of the time, at 55 and 52 percent, respectively.

In the final group match, Chile attacked for most of the game, but van Gaal’s team scored twice in the last 15 minutes to win 2-0 when La Roja tired and dropped off, much as Mexico did as a response to being up 1-0 with just 30 minutes remaining.

Chile was a perfect contrast to the Dutch with its high-pressure system based on collective work rate. In the round of 16 on Saturday, Brazil only completed 69 percent of its passes in the first 90 minutes before Jorge Sampaoli’s side ran out of gas again and played to survive extra time without losing.

In Chile, the three-back system started with Marcelo Bielsa, nicknamed “El Loco” for the radical tactical permutations he implemented with the national team. Bielsa is a theorist akin to a quantum-mechanical physicist, his strategies detailed like NASA launch code.

Sampaoli is one of many managers influenced by Bielsa. The list also includes Pep Guardiola, Gerardo Martino and Diego Simeone, whose Atlético Madrid team best resembles Sampaoli’s Chile in its defensive strategy and lethal counterattack.

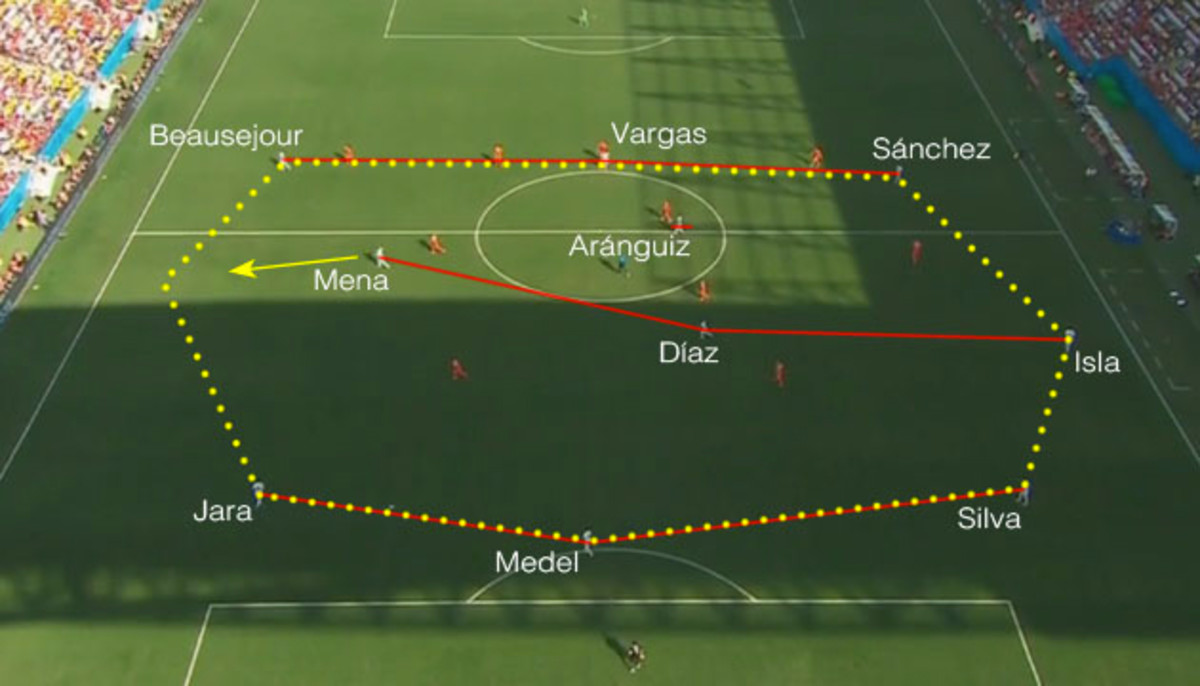

Sampaoli built on Bielsa’s system, but the chief feature remains: high defensive pressure that leads to immediate vertical play upon regaining the ball. Chile doesn’t play much in the central channel in possession. Instead, the wingbacks and attackers pull wide to find space created by the Chilean defensive swarm in the middle.

The players’ work rate allows the team shape to shrink and expand rhythmically depending on the location of the ball and the match situation. The center backs pull wide when building out of the back, and all three are comfortable with the ball at their feet, also advancing into midfield. Out of possession, the entire team squeezes centrally and applies pressure.

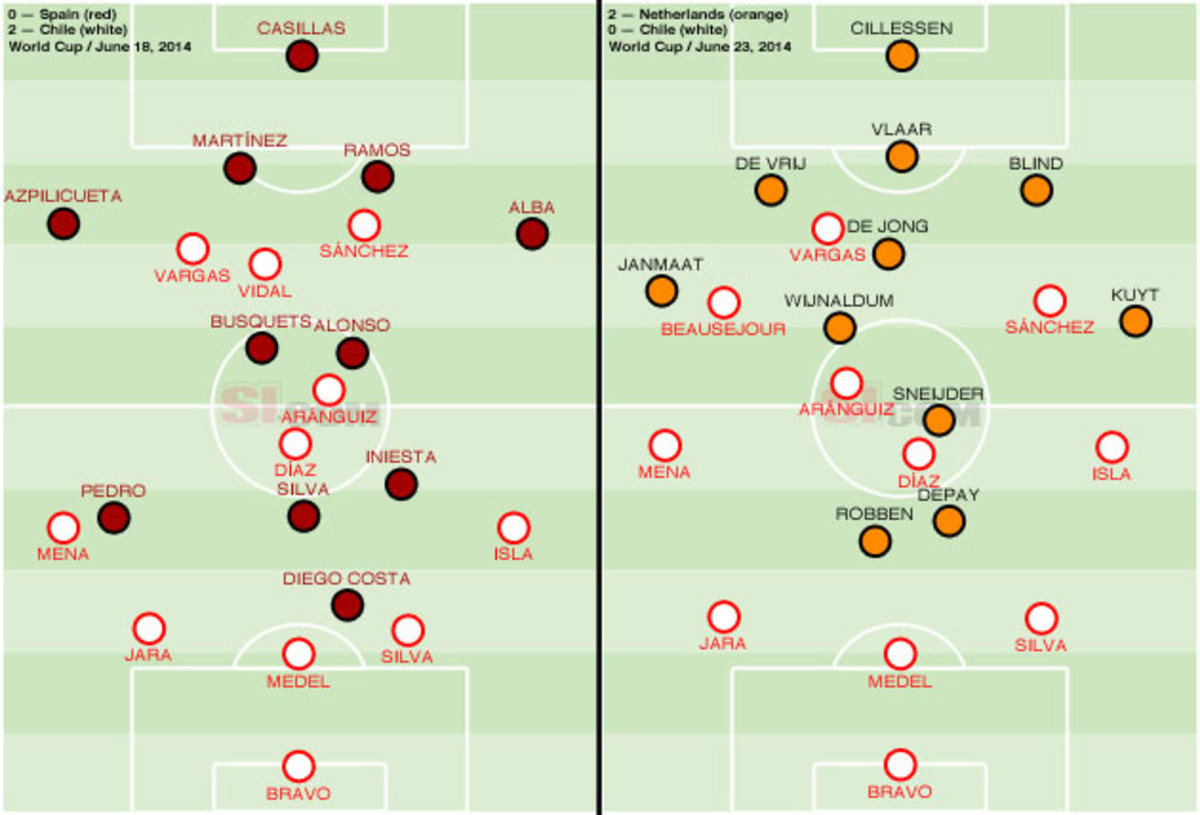

The difference in Chilean players’ average positions against Spain and the Netherlands shows the team’s dichotomy. Against Spain, the forward line stayed central to prevent easy play out of the back, with the wingbacks pressuring the Spanish fullbacks. Against the Dutch, Chile controlled most of the possession, necessitating a wider starting position from each player.

Against Spain, the shape could be best described as 3-4-1-2, with two holding midfielders screening the center backs and Arturo Vidal running the central channel to connect midfield and attack on both sides of the ball.

Against the Netherlands, it was closer to 3-3-1-3, the fringe players forming a circle around the field with Charles Aránguiz and Marcelo Díaz running the middle. (Coaches with possession philosophies will immediately recognize the shape as a field-encompassing rondo.)

Chile’s downfall was the same as Simeone’s Atlético in the Champions League final. It’s extremely difficult to play at the intensity necessary for a high-pressure system for 90 minutes, let alone 120. Simeone’s team gave up a back-breaking goal in extra time and ended up losing in a landslide, and while Sampaoli’s troops never conceded that goal to Brazil, they were physically spent and had to cling to the possibility of winning in penalties, spending most of the final half-hour inside their own defensive third.

Costa Rica’s three-back system also suffocates the middle defensively, playing a box-shaped central midfield. The Ticos’ shape becomes a flat 5-4-1 when the opponent gains obvious control in its own defensive third, using visual cues to pressure in midfield.

In attack, right-sided center back Óscar Duarte pushes higher than the left side, allowing wingback Cristian Gamboa to push higher and Bryan Ruíz to tuck in from the right wing alongside Joel Campbell on the front line.

Against Italy, Andrea Pirlo was pressured immediately any time he received the ball. With two Ticos as holding midfielders, one could always step to the ball, the indented winger on each side working to support his partner.

The three-back system is engrained in Italian culture, with catenaccio taking hold in the 1980s. The diamond midfield and 4-1-4-1 formations Cesare Prandelli used in recent times also packed the middle of the field, but he played 5-4-1 in the final group match against Uruguay, intensifying the effect.

Italy started with a triangle midfield and two strikers, moving to a diamond and a lone forward after halftime. Uruguay countered with its own three-back system, but instead of adding numbers in the middle, it played with a flat line of three midfielders who limited forward ball circulation and limited service to Pirlo.

Cutting off Italy’s ability to go through the middle meant the Azzurri resorted to long, diagonal balls and crosses into the penalty area. Uruguay kept numbers back, winning every aerial duel in its own 18-yard box and limiting Italy to two successful crosses on 18 attempts.

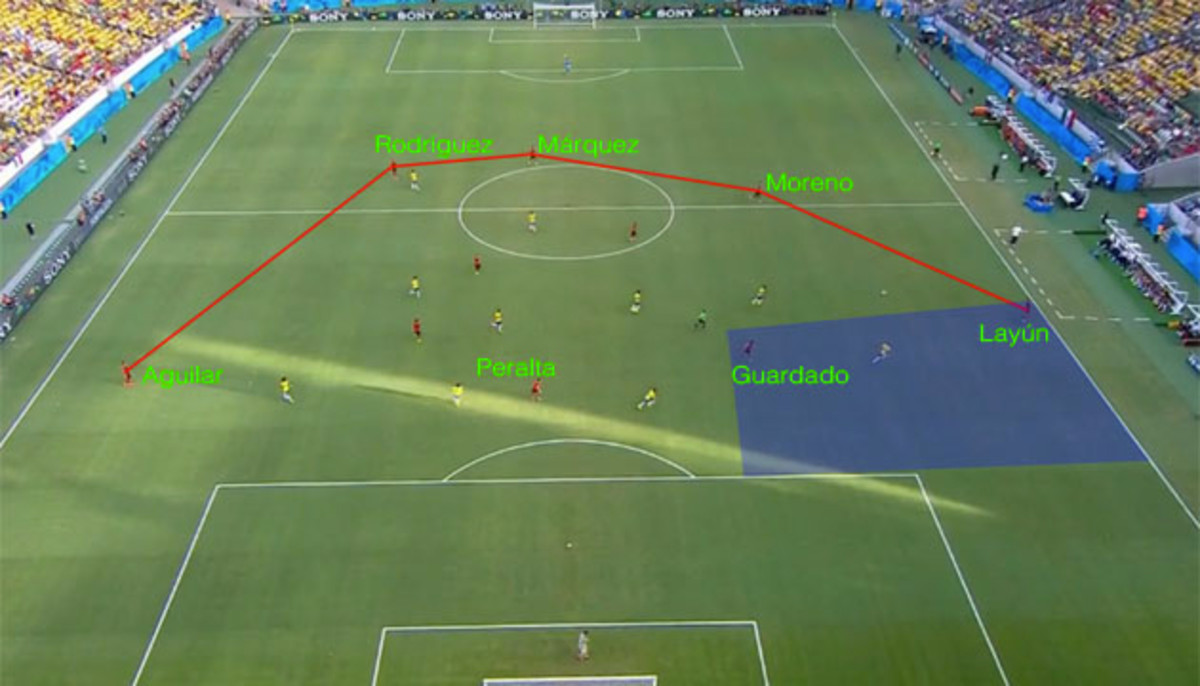

Uniquely, Mexico’s three-back system is not about central overloads but wide isolation. Wingbacks Paul Aguilar and Miguel Layún have freedom to get forward faster, and the top points of the midfield triangle, Héctor Herrera and Andrés Guardado, pull wide to create two-on-one situations.

The trend mostly applies on the left side, through Layún and Guardado. As the ball moves from the middle to the flank, Guardado runs wide to create the isolation. In the middle, forwards make third-man runs to exploit gaps in the opposition back line as defenders adjust.

Layún also cuts inside to combine or take long shots. At the same time, he rarely leaves the team exposed defensively. He was one of Mexico’s hardest workers this World Cup, recording the largest number of sprints in all four matches.

Heartbreak for El Tri: Three Thoughts on the Netherlands' win over Mexico

El Tri’s system presents a double-jeopardy situation to opponents: either defend the 2-on-1 and leave the middle open for the central midfielders and forwards to receive service, or leave the wide spaces open and allow easy combinations and crosses.

Defending and defensive-oriented tactics are alive and well among successful teams, even in a tournament of high-scoring matches and an era that has seen more goals than any before it.

The Netherlands — favored to make at least the semifinals — and Costa Rica won their groups with defense-heavy schemes, and Chile’s prowess without the ball was a perfect example of using an opponent’s possession to the defensive team’s advantage. At the same time, every team with a three-back system has provided moments of explosive offense on par with those fully engrained in the tiki-taka philosophy.

With the widespread knowledge of tactics in an age of technology and reflection, football may not see new advancements in that area. Instead, old ideas are likely to resurface and evolve to modernity through slight tweaks — man-marking center backs who can also build out of the back or teams that high pressure not just for 45 or 90 minutes at a time, but for tournaments and seasons in their entirety thanks to modern fitness training.

In a World Cup where new technologies are all the rage, whether it’s in the Brazuca, training regimens or player tracking that provides seemingly endless analytics, it’s the decades-old idea of playing three center backs that has been the most intriguing development.