Soccer-inspired graffiti a mainstay of Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian landscape

RIO DE JANEIRO -- Jorges Leon Brasil is not lost. He started chauffeuring tourists and businessmen and urban adventurers all over Rio 26 years ago, when he was 18. His time-tested version of GPS is to squint his eyes in deep thought and—pop!—Ah yes, I know this place. He’s just not sure where he’s going this morning.

A rest day during the World Cup has turned into a driving tour of Rio’s burgeoning graffiti scene, and I’ve asked Brasil—Junior to his passengers; he was named after his father—to be my guide in finding some soccer-inspired art. He has experience, after all.

As a young boy growing up outside of Rio in the 1980s, in Vista Alegre (“Happyville, you would say, in English”), Junior would join the local children at night during World Cup summers and literally paint the town center yellow and green, with Brazilian flags and soccer imagery celebrating his generation’s stars: Zico, Romario, Bebeto. . . It’s part of a tradition that carries on today.

Every Cup cycle, neighborhoods in Rio (and throughout Brazil) compete to create the most elaborate shrines to that year’s national team—streamers, flags and murals of the players, often painted mercilessly over the last squad, so that Hulk replaces Robinho who replaced Ronaldinho; Marcelo gets painted over Lucio; and so on.

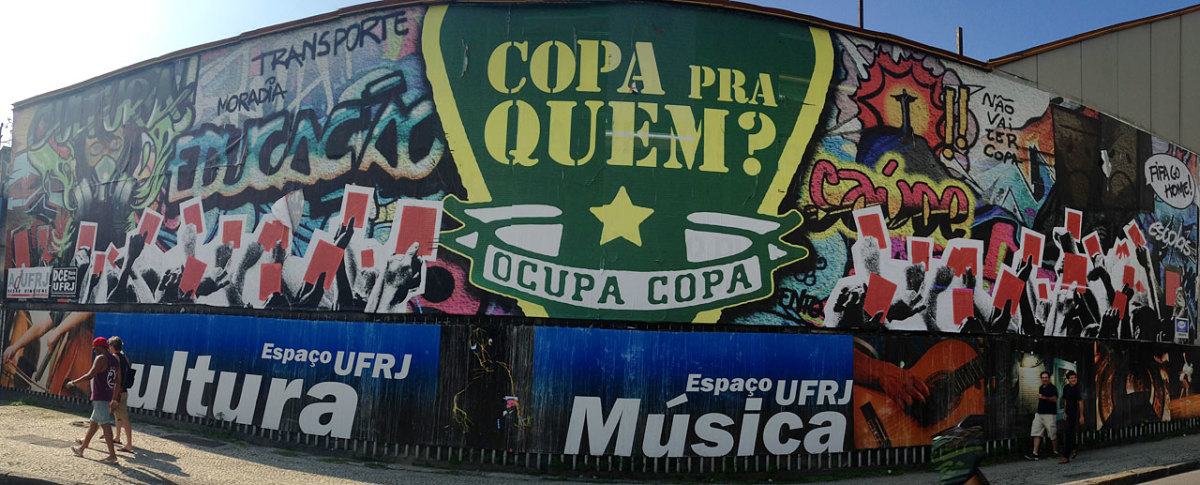

This is all part of the circle of life for an art form that is thriving here in recent years. In 2009, Junior explains, the Brazilian government decriminalized street art, which is to say that graffiti was made a thing of consent. You’re more than welcome to spray paint the stone embankment along the front of my business, as long as you ask my permission. (Tagging—or pichação in Portuguese—is still frowned upon.)

So it is on a drive from the airport to the top of the winding Santa Theresa neighborhood that one might encounter a cartoon depiction of Naranjito, the grinning orange-shaped mascot of World Cup 1982, on one block, and then a caricature of Neymar’s soap opera star girlfriend, Bruna Marquezine, around the corner. As a home or business owner one also has the right to approve the design, so one is less likely to come across, say, a cartoon depicting this year’s Cup mascot, Fuleco, gripping a wad of FIFA cash. But that exists. I just haven’t seen much of it. Maybe I’m looking in the wrong places.

What I’m looking for is the beautiful game depicted beautifully. This is what brought Junior and I to the brink of being, well, lost.

I learned earlier this week that a stunning new World Cup-themed mural had been spray-painted somewhere inside the Cantagalo favela that overlooks Copacabana Beach, and now we’re at the base of a daunting cobblestone incline, rocking gently back and forth in Junior’s stick-shift station wagon as we weigh our next move. Cantagalo, he tells me, pointing to a UPP sign, was pacified five years ago. The Pacifying Police Unit chased out the bad guys and set up shop. Now they patrol the streets constantly. It’s safe.

Our creeping drive up the hill, to a vantage point at the top of Cantagalo, does little to reassure. The officers Junior speaks of patrol in single file, their drawn pistols tethered to their utility-belted waists by thin retractable leashes like so many ID badges on the hips of cubicle-dwellers back home in New York. But here, every index finger caresses a trigger. This is just how it is in Brazil—at the bank in Ipanema, at the luggage area of the airport in Salvador.

Junior’s mental GPS is failing him at the worst possible moment, and for the first time in three days he asks for directions.

“Grafite da Copa do Mondo na Quadra do Pavao,” he is told by a smiling stranger who, it turns out, is happy to help this journalista.

Gra-fee-chee. Yes. In the Square of the Peacock.

Soccer-Inspired Graffiti and Murals in Rio

We’re pointed back down the hill by one pedestrian. And then back up the hill by another. And then, out of the car, down a narrow alleyway—barely as wide as my wingspan—that evokes M.C. Escher, all twisting brick stairways heading up toward nothing or down toward more nothing.

Only when I really start to squirm—when it hits me that I don’t belong here, that this isn’t a museum for me to explore, that maybe we should get going—do we turn a corner and sunlight spills in from above onto a secret town square that doubles as a soccer pitch, with metal-piped goals and drainage ditches forming one stone sideline.

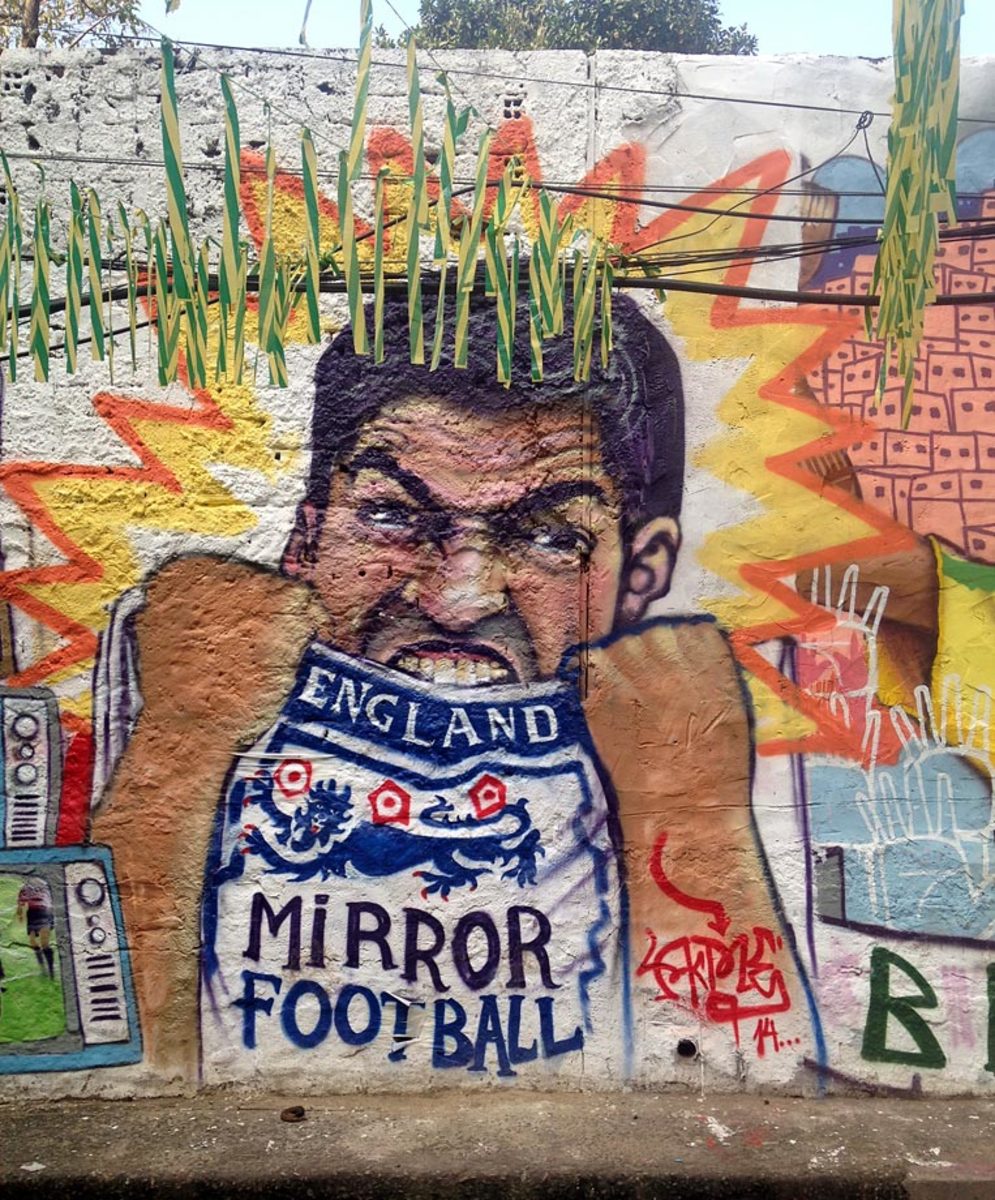

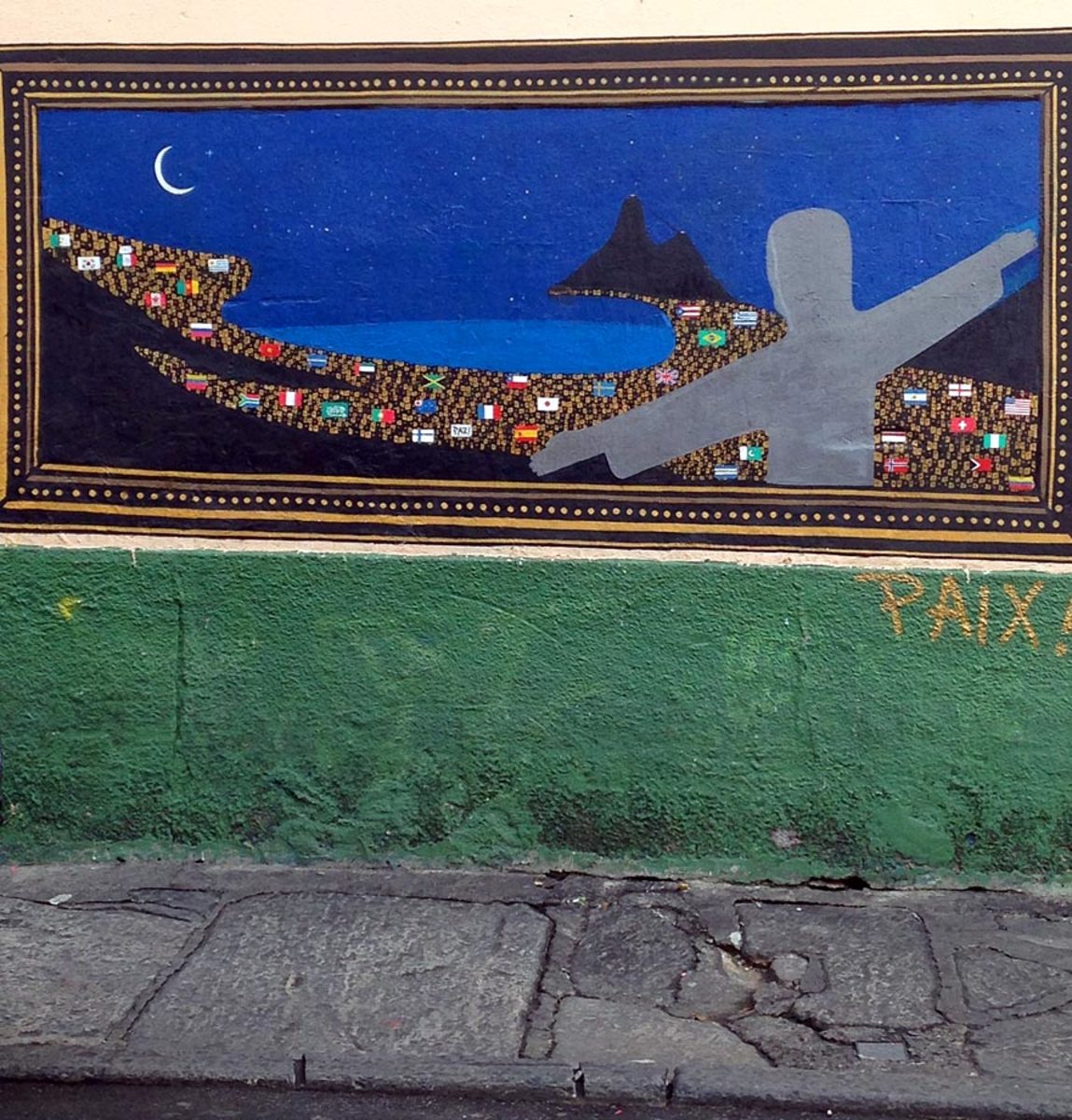

Along one wall, high above the beachgoers and beneath the traditional overhung yellow-and-green streamers, I find a depiction of (I’m later told) the artist wearing a Brazil soccer jersey and a type of bird headdress that is common at Carnival. And next to that, a tribute to the English team that recently departed this World Cup, with references to the Three Lions of years past: Winners in 1966; Paul Gascoigne’s sending-off in ’90; the WAGs of 2006; and, prominently, a biting loss to Luis Suarez’s Uruguay just one week ago.

There’s a hesitation to whip out a camera or an iPhone that comes with having spent two weeks in Brazil. This World Cup has been the tournament of goals, but also of things gone missing, at airports and on streets and in hotel lobbies. But this discovery calls for pictures. Not just pictures but wide shots and panoramas and video—and now out come the locals, not just kids but a few young men who could take out Junior and I in a heartbeat. My guide’s words from minutes earlier echo in my head: “Your dream! You are in a favela! A real favela!”

All they want is to share. Shame on me.

One of the locals explains: The artist is a 32-year-old favela-dweller who goes by the working name of ACME. I gawk and take pictures and drop my guard, and the tension eases. More sharing from the locals—two young laborers and some passersby—and I’m told that ACME drops his son off at school every day just around the corner; that after England’s embarrassing exit he had the idea to paint the Cup artwork alongside the paved pitch where his son plays, spending an entire day on the mural. It’s a thing of beauty, his painting—touches of humor and respect, with a nod to the square’s peacock namesake.

Wrapping up, saying goodbyes, Junior and I wind our way back through the impossibly stacked Duplo-block homes. We discover another mural on the way out, somehow left over and untouched from a Cup gone by: caricatures of Ronaldinho and Kaka, in the style of a boardwalk souvenir T-shirt. I snap away and then defer to my guide. Where to next?

Junior squints his eyes.