Brazil's national team, club woes are rooted in complex, long-term issues

BELO HORIZONTE, Brazil – Now that the dust has settled and the visiting fans and teams have packed up and gone home – their suitcases filled with for the most part happy memories – it is time to look back and reflect. And, most importantly, it's for Brazilian soccer to ask the question with the complex answer: What went wrong?

It is perhaps fitting that in this country blessed with such abundant gifts but cursed with a luckless history – colonization and slavery bleeding into a 21-year military dictatorship and now this modern Brazil, where a stable democracy is tainted by an often grubby and corrupt governing class – that the team left with the most regrets after this kaleidoscopic tournament is the host nation. Like the high school student with no date to the prom, Brazil was left looking sadly on from the porch as Germany and Argentina donned their best tuxes, climbed into the limo, and drove off into the night.

Ever since the devastating 7-1 loss to the Germans in the semifinal just over a week ago, Brazilian soccer has been tearing itself apart. The loss may not have sent shockwaves through the country’s society as much as the notorious Maracanço defeat to Uruguay in the final game of the 1950 World Cup, but it has rocked its most beloved sport – and iconic cultural export – to its foundations.

The Two Brazils Revisited: What does the future hold after World Cup 2014?

Not before time, many believe. “The CBF (Brazilian soccer’s governing body) talked about going to hell if Brazil lost. Let’s hope they go there and never come back, and that those who stay here use this defeat as a well-deserved lesson on which to base a better future, like the Germans did after the 2006 World Cup, by cleaning up the finances of the clubs, getting the fans back into the stadium, and creating a clean, beautiful game by punishing the corrupt,” wrote Juca Kfouri, one of the country’s leading sportswriters, in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper after the match.

Nor is the criticism a simple knee-jerk reaction to a humiliating defeat.

“I’ve been saying the same thing for 15 years,” wrote 1970 World Cup winner Tostão, a fierce critic of the current state of Brazilian soccer. “I feel like I’m repeating myself and that it doesn’t make any difference whether I speak or not. I’m sick of it.”

The problems facing the game in Brazil run deep. The average crowd at a top flight game is just 15,000 – lower than Major League Soccer. Fans are kept away not just by the often uninspiring quality of play on offer, but also by inconvenient kickoff times, governed by the TV broadcasters – 10 p.m. on midweek evenings is a common start time, once the nightly diet of novelas (soap operas) has been consumed.

Violence is another factor in keeping crowds down – there have been 234 (and counting) soccer-related murders in Brazil since 1988, mainly connected to the country’s notorious torcidas organizadas (hooligan gangs, or organized fan clubs, depending on your point of view).

Then there is the fixture calendar. Salvador Dali would have struggled to create anything as surreal. Before the national championship starts in May, Brazil’s top clubs play five-month state championships – the equivalent of, say, the Boston Red Sox spending five months of the year playing competitive games against the New Hampshire Fisher Cats or the Portland Sea Dogs.

Such games are often watched by hundreds, rather than thousands of people, and the ensuing fixture squeeze – a top Brazilian side competing in the continental Copa Libertadores, national championship, the Copa do Brasil and state championship can play well over 80 games a year – results in exhausted players and a bewildered, disinterested fan base.

Brazil falls short, but its World Cup provides unforgettable theater

Acres of empty seats are just one problem facing Brazil’s soccer clubs. All are in massive debt. A report last year by the consultancy firm BDO estimated that the accumulated financial black hole facing 23 of the country’s top teams was around $2.12 billion dollars, and non or late payment of player salaries is an all too frequent occurrence. Teams are controlled by elected presidents, most often political movers and shakers, who, once in power, run the clubs like their own personal fiefdoms, thinking only of how much silverware, and personal glory, can be collected during their short mandates. Long-term planning, financial or otherwise, is rarely a concern.

The short-term outlook extends to the fans. Brazilian supporters are deeply passionate and demanding, obsessed with outdoing their local rivals. This creates an atmosphere of impatience that pervades the game from top to bottom, resulting in managers being fired on a monthly, rather than yearly basis. Brazilian soccer is littered with previously promising young coaches who have had their confidence destroyed after racking up 10 or 15 club jobs in five years.

Terrified of losing more than a couple of games in a row, and subsequently their jobs, a win-at-all-costs mentality is often the only option for such coaches, which in turn leads to a direct, functional way of playing. As an example, the man rumored to be Luiz Felipe Scolari’s replacement as Brazil coach (perhaps the only realistic option, given the paucity of established coaching talent in the country) is former Corinthians boss Tite, a solid organizer and motivator but a man who has almost no experience of coaching outside Brazil, and whose greatest moment came when leading his club to a FIFA World Club Cup win over Chelsea by playing tightly organized, defensive and painfully dull soccer.

“Scolari is responsible for the national team, but he is not the creator of our current mediocre style of play,” wrote Tostão. “He thinks like other Brazilian coaches. They created a monster. I don’t know where this started, whether it was from the inside out, because of the narrow vision of Brazilian coaches, or if it was from the outside in, caused by greed, damaging the quality of our play…it is a national plague.”

Neymar's cultural significance to Brazil transcends soccer, World Cup

Such failings have until recently been masked by Brazil’s status as South America’s economic powerhouse, and by a steady flow of talent from a vast, soccer obsessed population. But the cracks are beginning to show, and not just in the national team. Last December Copa Libertadores winner Atletico Mineiro, featuring Ronaldinho and World Cup reserves Jô and Victor, were humiliated at the FIFA Club World Cup in Morocco by unfancied local side Raja Casablanca. This year no Brazilian clubs have made it to the Libertadores semifinals, and only one got as far as the quarterfinals.

The issue of playing style lies at the heart of the debate over what has gone wrong with the Brazilian game. In a country famed for playing the jogo bonito (the beautiful game), there is an expectation not just to win but to win by playing attractive soccer. The same attractive soccer that was perhaps best typified by one of the country’s most cherished World Cup teams – the magical side from the 1982 World Cup in Spain that featured Socrates, Zico, Falcão and other soccer sorcerers.

That team’s stunning elimination at the hands of Italy, coming as it did after two previous World Cup failures in Germany in 1974 and Argentina in 1978, was seen by many Brazilian coaches and administrators as confirmation that the jogo bonito was dead – overpowered by the more forceful, more physical European game.

Brazil began to mimic the same strategies – valuing physicality over finesse, creating generation after generation of uncompromising and uninspiring defensive midfielders such as Dunga, Gilberto Silva or Felipe Melo, while attacking strategies were concentrated around adventurous, flying fullbacks such as Roberto Carlos and Cafu. There were still moments of individual magic from geniuses such as Romario, Ronaldo or Ronaldinho, but the ball no longer flowed hypnotically from Brazilian boot to Brazilian boot as it once had. The fruits – or the nadir – of that policy were seen at this World Cup.

“As well as lacking a playmaker, Luiz Gustavo is too close to the center backs, Neymar is too close to Fred, and Oscar and Hulk are too far wide. Fernandinho (or whoever plays in his role) is as marooned as Robinson Crusoe on his island, watching the ball fly over his head,” wrote Tostão after Brazil’s narrow win over Chile.

Germany turns in signature showing with complete destruction of Brazil

In short – Brazil had no midfield. And while the hosts managed to sneak past Chile and Colombia playing scrappy, bickering soccer (the 31 fouls against Colombia were the most Brazil has committed in a World Cup game since records began in 1966), when they came up against a side with a truly top-class midfield – the Germany grouping of Toni Kroos, Bastian Schweinsteiger, Mesut Ozil and Sami Khedira, among others – Brazil had no answer. The results were harrowing to watch.

Overseeing this turmoil is Brazilian soccer’s governing body, the CBF, an organ emblematic of the institutionalized corruption that dogs the country. When former president Ricardo Teixeira resigned after years of accusations of graft (he now lives a life of gilded exile in Miami), the job went to the then 79-year-old Jose Maria Marin on the basis that he was the oldest of a coven of vice-presidents. The toxic Marin makes a fine pantomime villain. Soon after being confirmed in his new role, video footage emerged of him snaffling a winner’s medal from a youth team awards ceremony, leaving one of the young players empty-handed.

Marin and his soon-to-be replacement Marco Polo Del Nero are symptomatic of the cronyism of the CBF, where each of Brazil’s state federations has the same number of votes (one) as the country’s biggest clubs. One such federation is in the state of Roraima in the north of Brazil, where the local championship boasted only six teams in 2013, and where president Zeca Xaud has been in charge for 39 years.

Marin and Del Nero are seemingly oblivious to the problems facing the Brazilian game. Both were reportedly keen to keep coach Scolari in charge of the national team after the World Cup, despite the devastating defeat against Germany and subsequent spineless loss to the Netherlands in the third place playoff. After the manager’s exit this week, Marin said “Scolari and his coaching staff were responsible for making the Brazilian people love their national team again.” The response of the Brazilian people to this remarkable claim has, perhaps wisely, not been recorded.

On one level, it could be argued that the Brazilian club game matters little, considering that only four on the country’s World Cup squad play here, and of those only one, the hapless Fred, was a starter. But Germany, and before that Spain, has shown that a long-term, joined-up program of development, including academies, national youth teams, and a healthy club game, can transform a nation’s soccer culture by encouraging the growth of young players and coaches and promoting a cohesive, attractive style of play.

“Belo Horizonte witnessed a clash between two eras of soccer. The past and the future on the same pitch. A state of the art smart phone against pigeon mail, old, tired and sick,” wrote Andre Kfouri, Juca’s son, in Lance! Magazine, Brazil’s leading soccer daily. “This epigraph at the Mineirão is made even worse by the fact that it was written by a team who seem to want to pay tribute to the style of soccer that Brazil used to play. A style of play that we decided to leave behind…the only choice now is start again from scratch.”

2014 World Cup: Looking back at the best and worst from a month in Brazil

Help may be on the way in the form of Common Sense FC, a player protest group. Emerging soon after the mass anti-corruption (and in part, anti-World Cup) street demonstrations of last year, the hundreds of players involved in the union are demanding a reformed calendar, and that clubs pay player salaries on time. But there is also the sense that the group’s real target is the sloth and sleaziness of the CBF leadership in general. Questioning the democratic structure of the organization, Common Sense FC published a document on Monday titled “Why the World Cup tragedy will not affect the CBF,” before revealing the mechanisms used by Marin and friends to ensure that power does not slip from their hands.

Last year the group staged a number of high-profile protests at league games, where players stood motionless with their arms crossed after kickoff, or most memorably, during the São Paulo vs. Flamengo match, passed the ball gently back and forth between the teams for a few minutes. “This has a much greater significance than they will ever imagine,” said veteran São Paulo goalkeeper Rogerio Ceni afterwards.

Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff is a supporter of Common Sense FC, and has also called for a major overhaul of the country’s domestic game.

“Our players shouldn’t be exported abroad. If we’re the sixth or seven biggest economy in the world, we should be able to keep them here,” she declared.

New legislation – the law of Fiscal Responsibility in Soccer – is being proposed to force clubs to honor their financial obligations, in return for a restructuring of their debts with the state.

“After the hour of sporting glory comes the hour of suffering…losing touches something deeper than victory, losing is to find the place where everything slowly starts to begin again from defeat,” wrote the great Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade.

It is clear that Brazilian soccer desperately needs to begin again. If the defeat against Germany is the spark for such change, then that humiliating afternoon in Belo Horizonte will have been a small price to pay.

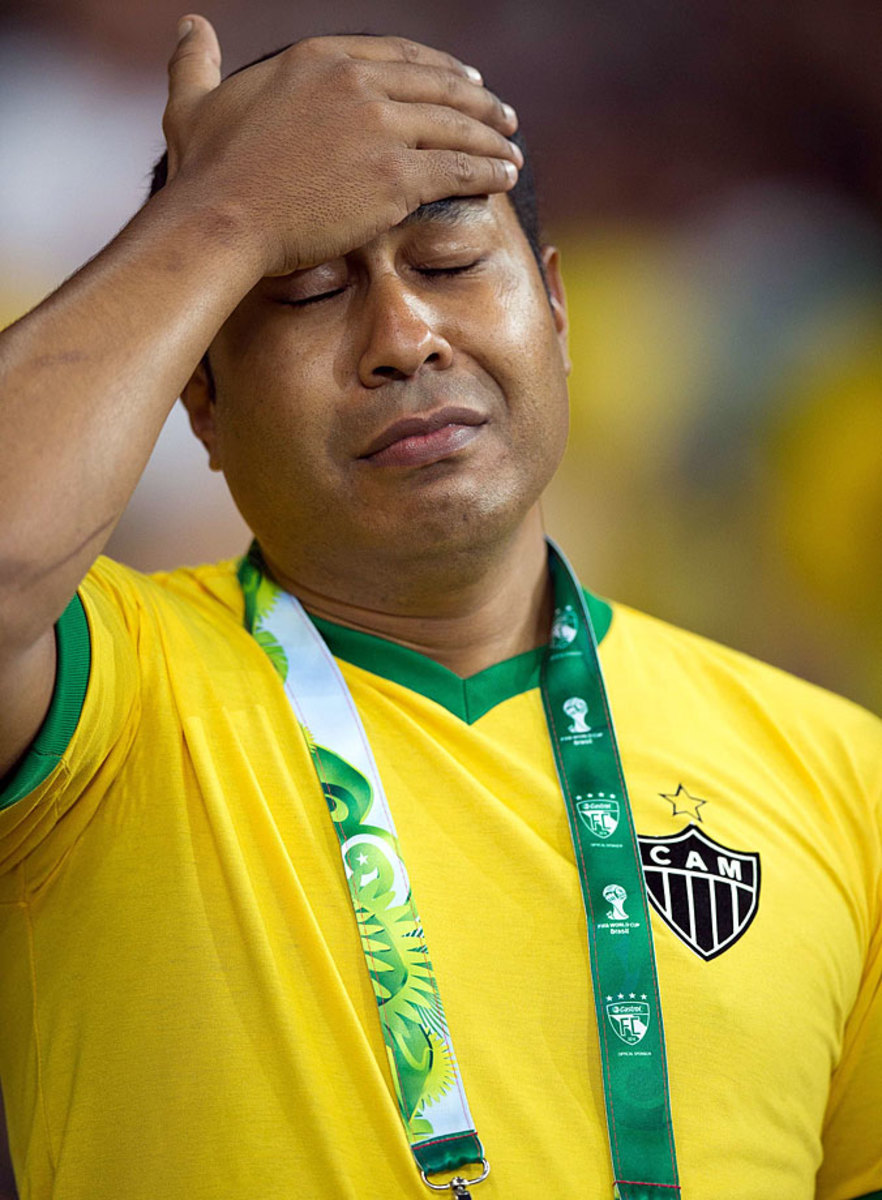

GALLERY: Distraught Brazil fans

Distraught Brazil Fans