Positioning, possession, pressure define Barcelona's famous philosophy

Few teams are spoken about and imitated as much as FC Barcelona, with its famously fluid style of play and ideas of footballing evolution. The "Barcelona Way" requires high technical quality and a particular interpretation and comprehension of the game.

Not many players can say they fit into the culture and wore the blaugrana shirt at Camp Nou. The philosophy that drives Barça’s selection and working methodology breaks down into three “Ps”: positioning, possession and pressure.

Positioning provides the framework for Barça’s famous individual and collective creativity, the freedom that only becomes possible from understanding the structure and its requirements.

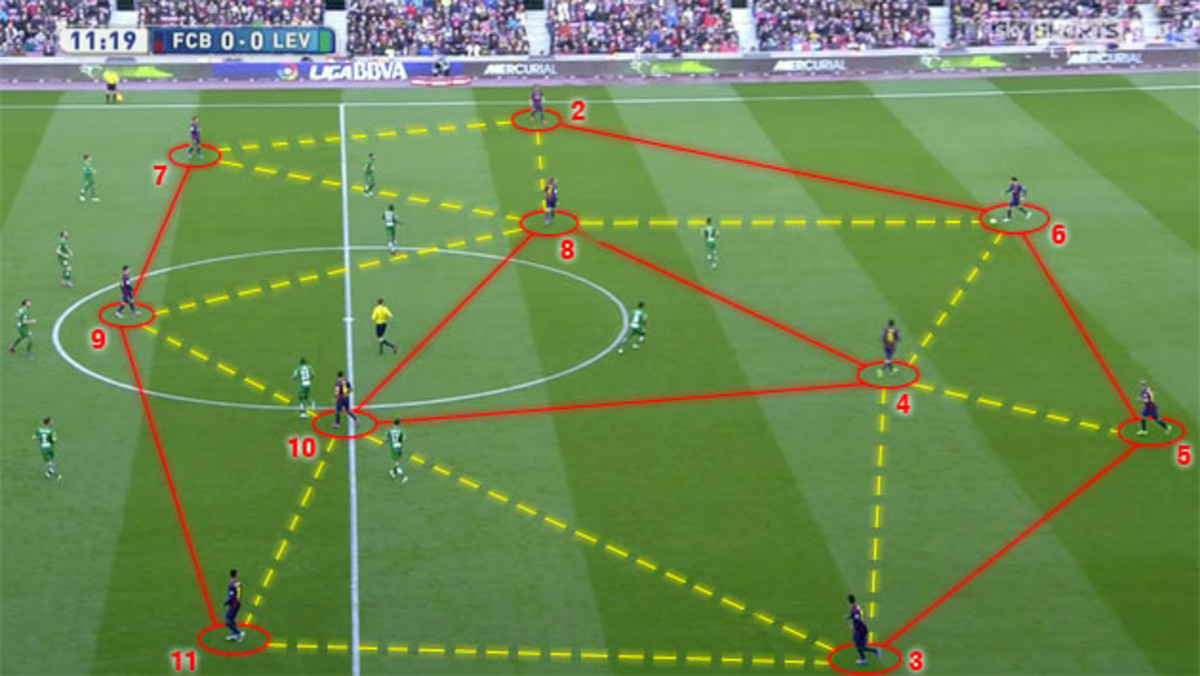

In basic nomenclature, Barcelona plays 4-3-3 with a single pivot. This shape gives the team easy ability to create triangles of support with short distances between players. Players can overload any area of the field, particularly the middle, with simple off-ball movement.

The starting shape provides support in width and depth for the player in possession, and players 1 through 11 all must be comfortable with the ball at their feet.

This overloading style translates directly from the rondo (5-v-2 keep-away-style) exercises that form the basis of Barça’s training methodology.

Sergio Busquets has been synonymous with the No. 4 pivote position since Pep Guardiola’s managerial days, becoming a world-class holding midfielder under the man who played the position himself at Barcelona.

He plays underneath two creative midfielders, usually Ivan Rakitić and one of either Xavi or Andrés Iniesta. The latter two have seen their playing time reduced under Luis Enrique, who has favored Rakitić and Rafinha to Spain’s aging superstars.

These two midfielders fill in central gaps between the three forwards. Building play from the back, the pivote stays withdrawn centrally, and the creative players generally occupy the half-spaces, the dangerous areas at the width of the penalty area.

The wingers tuck inside in the attacking third, again to overload the middle. On the left, Neymar generally stays wider and looks for opportunities to run at defenders one-on-one. Lionel Messi moved back to right wing recently, where he started under Guardiola before playing the center-forward position, now occupied by Luis Suárez.

Messi remains the most active frontrunner, cutting inside and changing spots with Suárez. Against certain opposition, Enrique will still play Messi in the No. 9 role, where he drops into midfield and creates a diamond with the three central players.

However, high overloads are easier for Messi to create from wide areas. Playing him on the wing also allows Suárez to make intelligent runs wide or inside as required; he has good understanding of when to surge forward and when to pull back, holding the ball up for teammates.

Barcelona’s possession protects the ball, not only moving closer to goal and creating opportunities, but also keeping opponents away from their own penalty area. In Barça’s philosophy, the team that owns the ball, owns the game.

Players learn to cherish the ball from the earliest ages at Barcelona’s famous La Masia academy. The idea is that every footballer wants to have the ball—nobody wants to defend—so it has to become an extension of every youngster’s foot. Only with the ball can players truly enjoy the game.

Mobility without the ball, receiving with the correct body position (hips square to the field) and setting teammates up for success are core principles of attack, as is being able to process images of the game efficiently.

In one experiment, the club followed Xavi for an entire match with cameras and found that he looked away from the ball at other areas of the field 804 times in 90 minutes. “Checking their shoulders” allows players to maintain a current picture of the entire field at all times.

Ball movement isn’t just about completing one pass successfully; it’s about putting teammates in position to complete the subsequent pass successfully as well.

Barcelona frequently changes the point of attack by circulating possession through its single pivot. Busquets frequently receives across his body, another technique taught at La Masia from age 8, allowing him to either play the opposite side of the field or pull it back the same direction.

Changing the point of attack unsettles opponents’ defensive shape, creating gaps in defensive and midfield blocks as players shift. Long passes can accomplish this, such as diagonal balls over the top to weak-side wingers, but Barça prefers to keep the ball on the ground and play more precise, shorter passes from one side to the other.

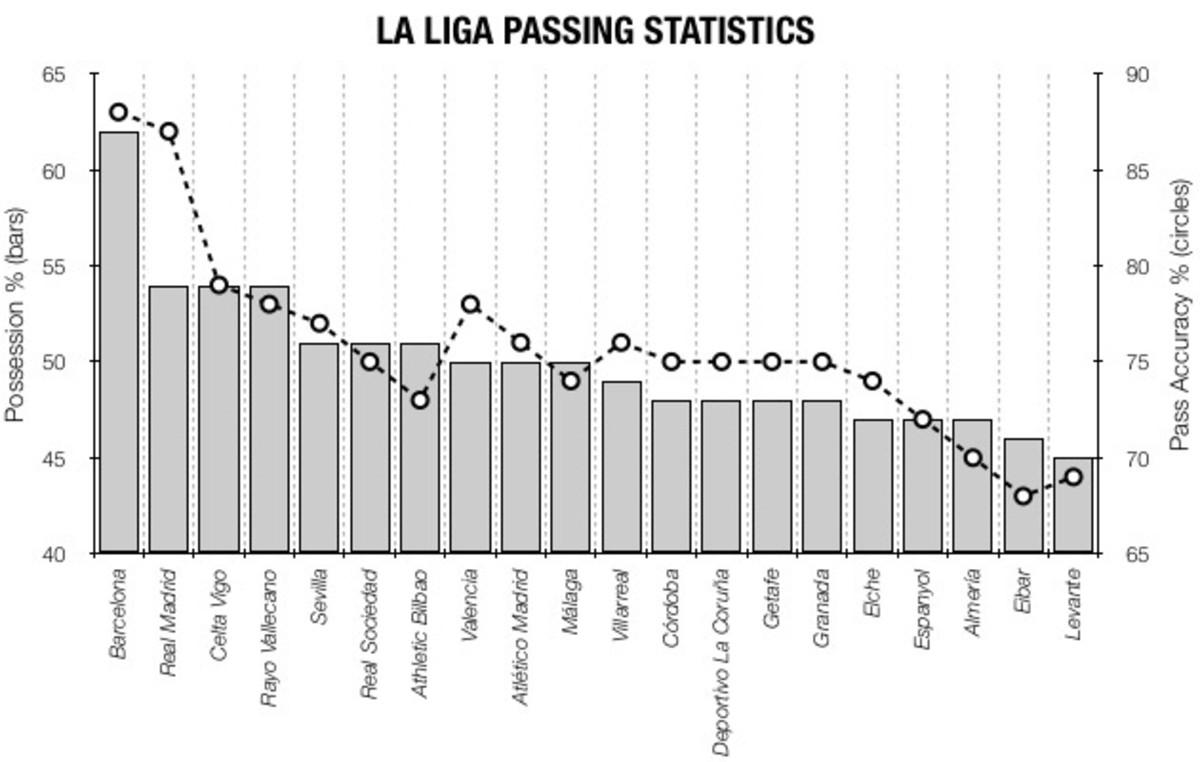

Across La Liga, Barcelona is the only team that averages greater than 55 percent possession, also completing 88 percent of its passes. Real Madrid completes 87 percent, but its average possession sits at 54 percent. Barça also has the shortest average pass length in the league at 16 meters.

Barcelona’s use of half-spaces has become a crucial element in possession. Having a wider angle of possible options for the next ball in an area less crowded than dead center of the field creates unpredictability for the defense.

This emphasis allows players to receive in spaces between defensive lines vertically and horizontally. Barça focuses on building through half-spaces until the final third, when efforts shift to combining through the central area on top of the penalty area or finding wide isolation.

When wingers have the ball at their feet below the penalty area, they dribble into the half-spaces.

Within the length of the area, they have a green light to take players on or find overlapping runners to penetrate to the endline.

Its combinations — instinctual one-touch play in crowded spaces — is what fans have come to associate with Barça. Creative midfielders slot into the gaps between the forward three, the wingers tuck in to create an overload and the fullbacks time their runs forward at critical moments.

An opponent’s best hope is often to play with an extremely low block defensively, concede the majority of possession and play on the counterattack. Málaga did it well in its 1-0 win over Barça on Saturday, all 11 players in a 4-4-2 within 35 yards of goal, leaving no gaps to penetrate.

In the Barcelona philosophy, the best defense is not losing the ball. The ball runs more than any player on the team, and players are also less tired when they don’t have to chase the game.

It doesn’t always result in a win, as Saturday showed, but it usually gives the team with more possession a higher probability of winning because it’s more likely to create scoring opportunities.

When Barça does lose the ball, its immediate pressure aims to recover it as high up the field as possible. Most teams have a tendency to step backward and regain defensive shape after losing possession, but the Barcelona philosophy asks players to step forward and chase right away.

It’s a far less comfortable system, but it can pay off in the form of goalscoring chances.

No individuals are spared the responsibility of working smartly to get the ball back, utilizing a high work rate and focus. The forwards initiate relentless pressure in the moment Barça loses the ball as the first line of defense.

Barcelona strives for continuity of its identity, the latest evolution in which came during Guardiola’s tenure. Subsequent teams are highly unlikely to match the six trophies Guardiola won in 2009, but the underlying philosophy remains.

Barcelona head of methodology Joan Vilà presented on the club’s style of play at the 2015 National Soccer Coaches Association of America Convention in Philadelphia last month, saying, “Our game is an idea—our idea,” and it persists because “the history of Barcelona asks it of us.”

Everything at the club happens according to the model that has been in place for decades. Still, despite the recent resurgence under Enrique that saw him match Guardiola’s record of 11 consecutive wins in all competitions, the current team has fallen behind.

Since Guardiola left, Tata Martino lasted only one season. The club will hold early elections for the board after the current season, and rumors of discontent with Enrique and club president Josep Maria Bartomeu’s leadership persist, not helped by the transfer ban that lasts through 2015 for breaching signing rules regarding young internationals.

Just as a return to Barça’s roots has been key for Enrique to regain some control and put together a strong run that ended against Málaga, members will be looking for an embodiment of the club’s strong tradition moving forward.

To evolve again, Barcelona needs leadership willing to return to the culture of innovation that drove the club during the days of Rinus Michels, Johan Cruyff and Guardiola.