How Barcelona's tactics helped it beat Juventus in Champions League final

As long as it played to its capabilities, Barcelona always seemed likely to win the Champions League final against Juventus on Saturday. It did just that, taking its fifth European Cup with a 3-1 victory while controlling most of the match with its flexible possession.

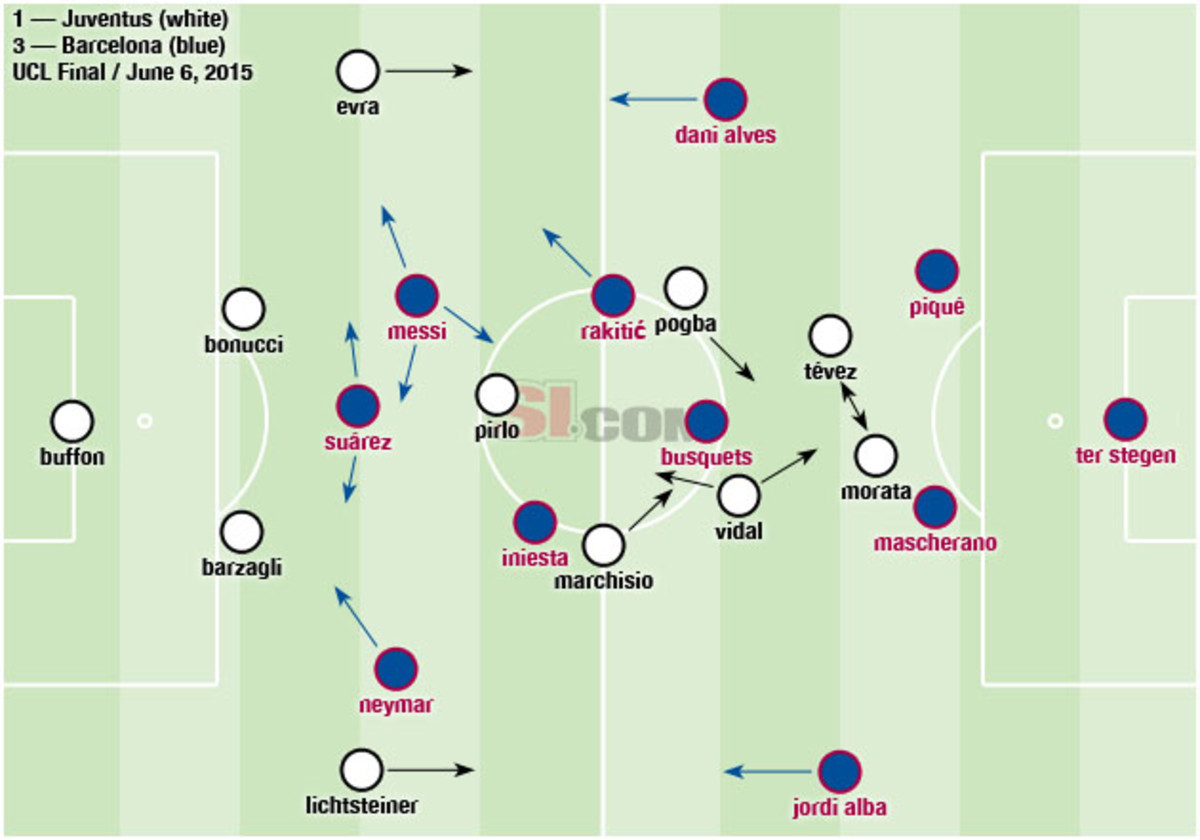

Barcelona’s unchanged lineup set out in its traditional 4-3-3 system. Neymar played wider than Lionel Messi, who cut inside as a situational No. 10. A relatively flat line of three in midfield filled in the front line’s gaps, and the fullbacks also provided width when the forwards tucked in.

Barcelona's Champions League title caps season, adds to dominant era

As usual, Luis Enrique’s team focused on allowing maximum freedom and flow among the top three players. Luis Suárez roamed side to side and checked back into midfield to both find the ball and make space for his teammates’ runs.

Defensively, Barcelona's ability to cover passing lanes and quickly recover the ball stifled Carlos Tévez’s linking play between midfield and attack for Juventus, which lacked the ferocity of the semifinal against Real Madrid. Sergio Busquets possesses a different skillset than a traditional No. 6, but his positioning often entices mistakes before he has to make a tackle.

Juventus also played its usual formation, a 4-1-3-2 with a narrow midfield that shifted between a diamond shape and a flat line. Tévez and Álvaro Morata roamed the highest spaces, with Arturo Vidal shuttling between midfield and attack to provide balance.

Europe's best, Barcelona finishes treble run with 3-1 win over Juventus

To begin both halves, Juve pressured high with its forwards and at least two midfielders, making it difficult for Barcelona to play out of the back. Barça defenders made some simple errors attempting passes, although Juventus couldn’t capitalize.

After a shaky period at the beginning and after the break, Barcelona again worked the ball out of defense effectively.

The Italians’ narrow midfield typically clogs central spaces for opponents to play through, but Barcelona’s ability to both circulate possession through the middle and utilize wide spaces proved key in overcoming it once the ball advanced out of the defensive third.

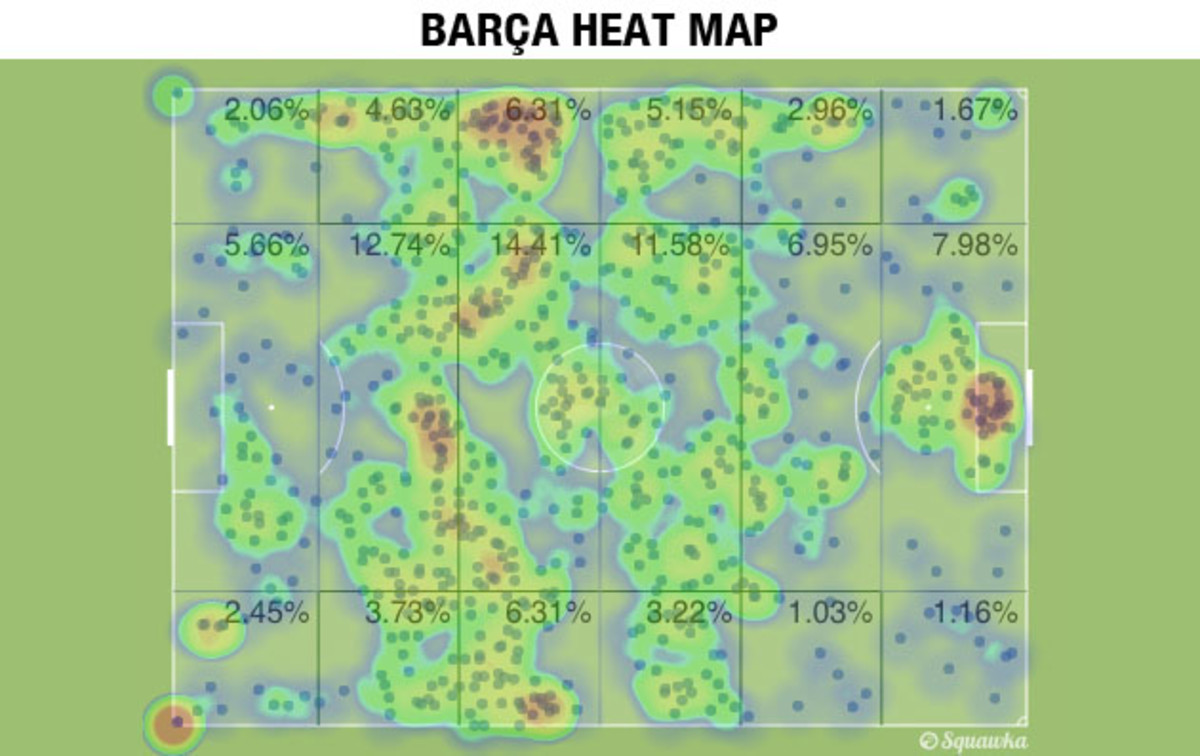

Rather than being dissuaded from passing in the central channel, Barça moved the ball around until it could use the middle area to create chances. The team’s attacking flexibility and situational awareness in the middle third ensured its dominance, keeping 61 percent possession throughout the match.

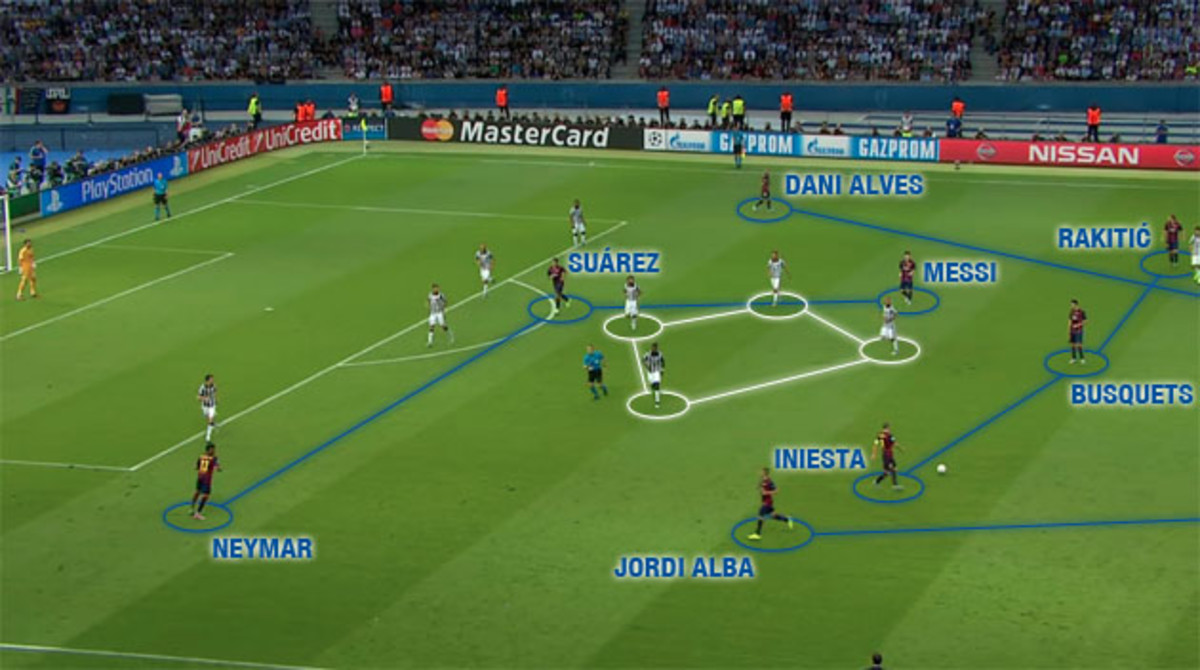

Juventus had to decide whether to sacrifice the compactness of its midfield shape by pressuring in wide areas or to pull a fullback out of position to deal with players on the flank. Barça waited and reacted; if the Juve midfield stayed compact, it would circulate the ball around the middle block.

If the midfield flattened out, the attacking players tucked in and allowed the fullbacks to provide width. Whether the central midfielders probed centrally or wide, Barcelona was ensured an overload because of the numbers it threw into attack.

Barça mixed its midfield and forward lines with Juventus’ middle block, forwards dropping between lines and midfielders probing any spaces they could find. As usual, the Catalans out-passed their opponents all over the field but especially in the highest portion of the middle third.

Overloading the central space provided an additional attacking area that Barcelona exploited on its first and second goals: the weak side via a quick switch. Messi cut in as he typically does, but his most dangerous moments came when he stayed within the right-side half-space and drew defenders toward him.

(In tactical theory, the half-spaces run the length of the pitch and sit on each edge of the penalty area. Their existence allows the central channel to be broken into three strips and analytical distinctions to be drawn between attacking from dead center and from just off-center.)

A team only needs to utilize enough of the field to stretch the opponent’s defense, so depending on its compactness, it might not take much width to accomplish. Because of Juventus’ shape, Messi could switch the ball just from one half-space to the other, rather than a more difficult ball to play and control to wider areas, and the defense instantly became stretched.

On the first goal, he pinged a ball to Jordi Alba on the opposite border of the penalty area, and Juve couldn’t scramble back before a quick combination ended with Ivan Rakitić’s finishing touch. A few times throughout the game, Messi changed the point of attack similarly, always diagonally so the pass broke both horizontal and vertical planes in Juve’s defense.

He’ll sometimes do this on the dribble as well, picking the ball up on the right flank and cutting across toward the opposite corner flag. That will eventually open space for him to shoot—as on the second goal on Saturday—or slip a ball through the opposing back line to a supporting teammate, of which Barça doesn’t ever seem to lack.

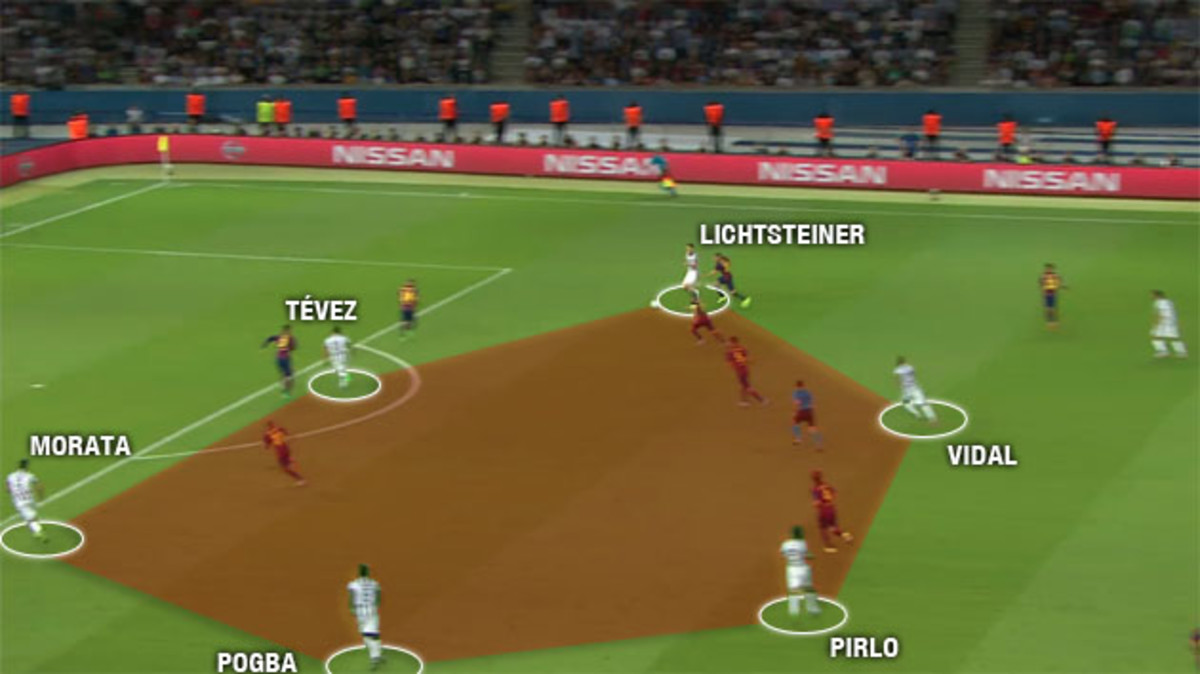

Its willingness to throw numbers forward only became dangerous in transition moments from attack to defense when it couldn’t win the ball back fast enough on Saturday. Juventus showed high acumen on the counterattack all season and again got its best chances of the match on the break against Barcelona.

Most of those opportunities, including the goal it scored, didn’t come in numbers-up situations. Instead, Juve focused more on getting the ball forward quickly and running at the defense, attempting to cause poor decisions from opponents. That style of counterattacking only requires equal numbers to be effective.

Stephan Lichtsteiner did just that with his run on the right flank in the build-up, helped by Claudio Marchisio’s intelligent backheel that sprung him. From there, it became a series of one-on-one duels, which Tévez and Morata both won against their markers.

Barcelona 2009, 2015 represent spirit of coaches Guardiola, Luis Enrique

Juventus could only get one such chance to fall kindly, as players missed opportunities in front of goal the rest of the time. Of course, Barcelona has also shown a renewed appreciation for the counterattack this season, and it wasted a few chances of its own on the break before Neymar’s goal late in stoppage time finally sealed the result.

Enrique instilled this new type of directness because of his attacking trident of Neymar, Suárez and Messi. Getting the ball forward—and thus at their feet—as quickly as possible has become Barcelona’s new style, rather than the hypnotic passing moves in the middle block it played under Pep Guardiola.

Unlike Juve’s counters, in which players run purposefully at the nearest defender and commit them to making a decision, Barça relied on its fast passing when it ran forward on the break. The two styles made for an interesting contrast, but were it not for Juve goalkeeper Gianluigi Buffon’s heroics in those situations, the match wouldn’t have been as close.

Ex-teammate, La Masia coach recall Lionel Messi's early days, persona

Barcelona deserved its victory, and it was the best team in Europe throughout the season. The Enrique revolution, wildly unpopular at first, really worked once everybody at the club seemed to buy in. His style clashes with Guardiola’s at Barça, but it was a necessary change that reflected the tactical evolution taking hold in the general game, largely in response to the passing machine of Guardiola’s era.

Ever the forward-thinking club, Barça prides itself on being at the forefront of football’s transformations. Rinus Michels, Johan Cruyff and Guardiola all took the club and the sport forward in that respect in their time at Camp Nou, and Enrique made his shift for the same reason: tweaking the underlying Barcelona philosophy just enough to maintain its identity but keep up with the modern game.

Despite the resistance he faced, Enrique dragged the club forward through another one of those evolutions in the greater sport. His reward this season was three trophies with his name on them.