After colorful soccer career, Jorge Campos enjoys low-key second act

Midnight on a spring Wednesday at LAX finds Jorge Campos about as motionless as when he roamed the goalie box—and the rest of the campo—for the Mexican national team throughout the 1990s. He is hustling from a long-term parking garage toward one of the dozens of flights he will catch between California and Mexico this year, his nomadic ways having changed far less over the years than his manner of dress. The gray jeans and sweater Campos wears as he enters Terminal 2 represent a complete parching of the palette that once splashed neon in every conceivable color, often all at once, across his custom-made goalie kits.

“I’m flying to Mexico City,” Campos says in Acapulco-accented English when a stranger asks where he’s headed. “I have to work.” And at this he laughs, his hazel eyes still large and expressive, his tanned 49-year-old face still wearing the glow of youth. Work, for Campos, means providing color commentary on international matches broadcast by Mexican TV giant Azteca, and that’s what he finds funny: “I get to talk about soccer,” he says, arms spread in apology. “They seem to think I learned a little bit when I played.”

The diminutive Campos (at 5’ 6”, he’s a full foot shorter than Chelsea goalkeeper Thibaut Courtois) didn’t play futbol as much as he experimented with its boundaries. Over the 130 international matches he played wearing Mexico’s colors—or, rather, wearing his own colors while competing for Mexico—he became known not only for his acrobatic saves and punchaways, executed in leaping rainbow arcs in front of the Mexican goal mouth, but for the threat he posed afterward: that he might rise from the pitch, roll the ball to himself and dribble upfield on the counterattack. Today, with rare exception, that kind of thing is reserved for the fetishist corners of YouTube. Campos showed off that unpredictability in some of the world’s largest stadiums, where he’d just as soon create a shot as pluck one out of the air.

On second thought, maybe playing is exactly what he did.

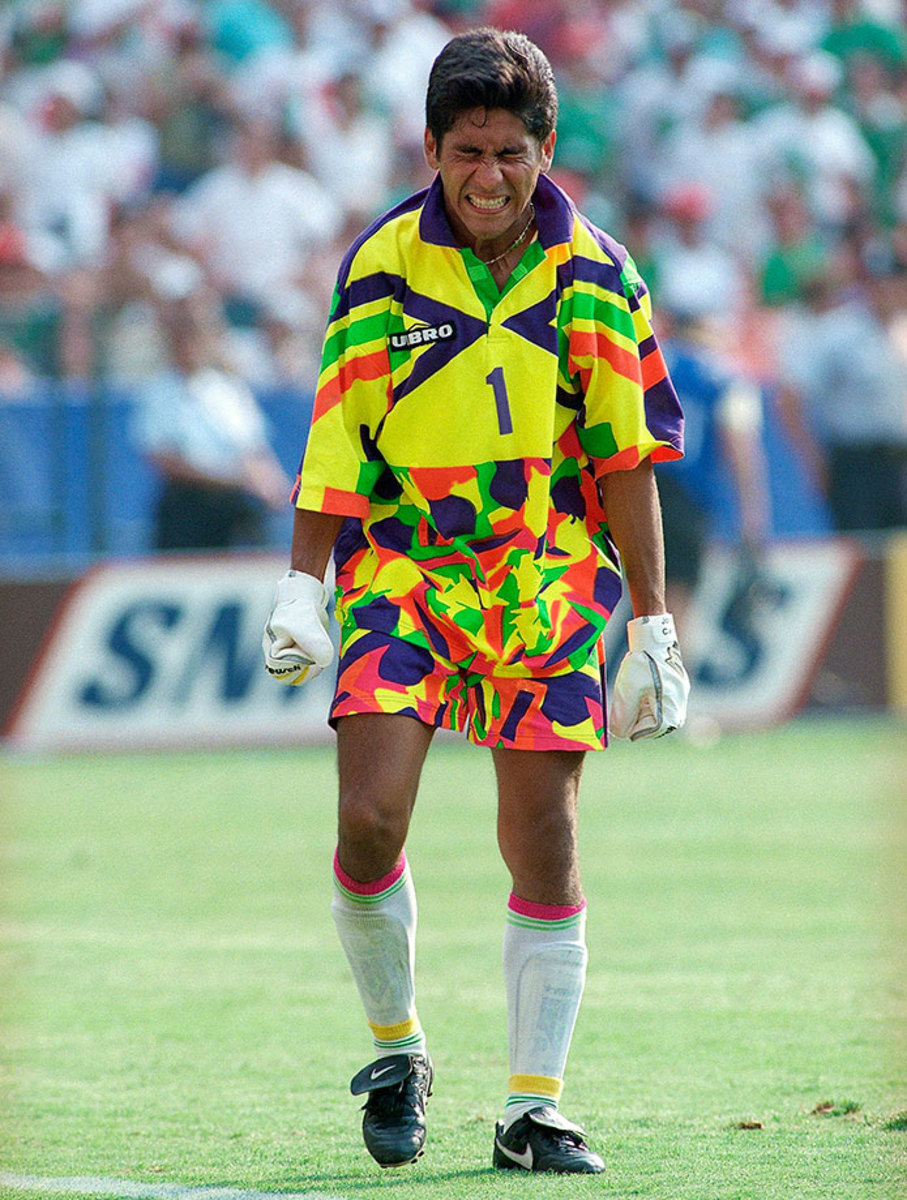

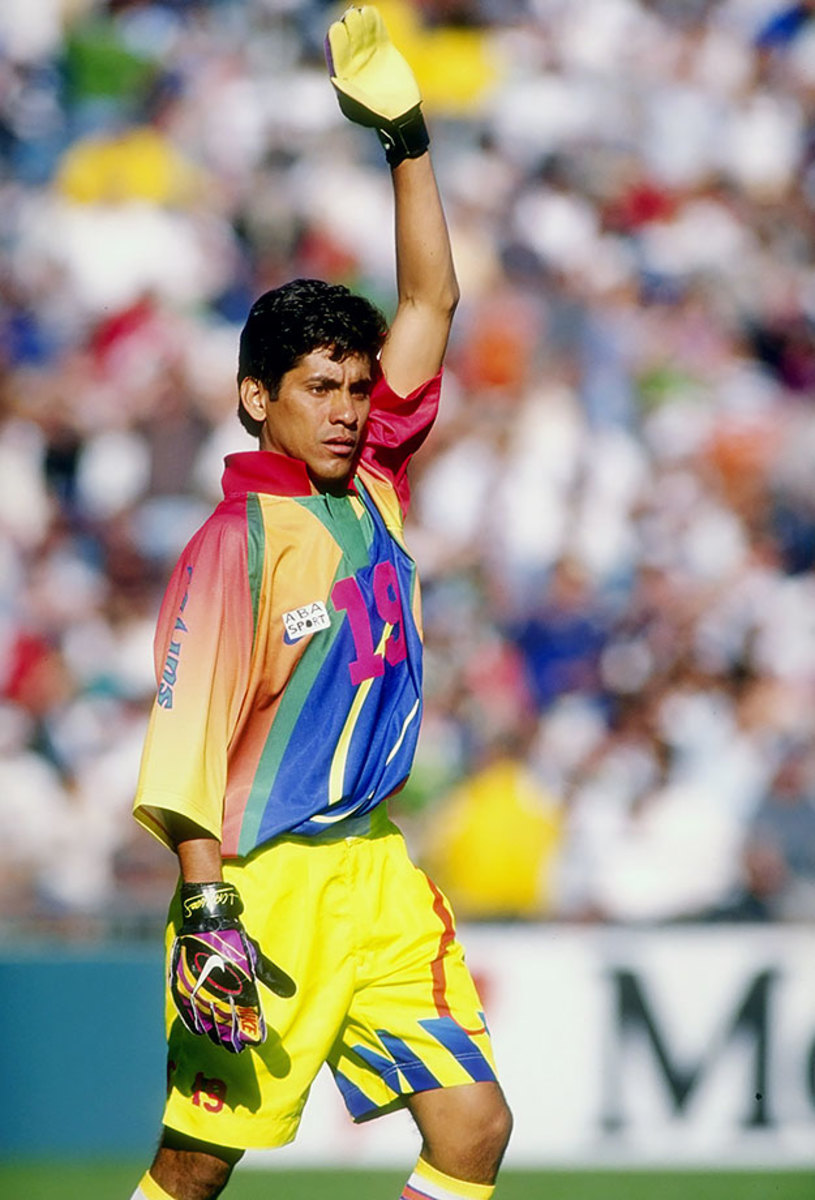

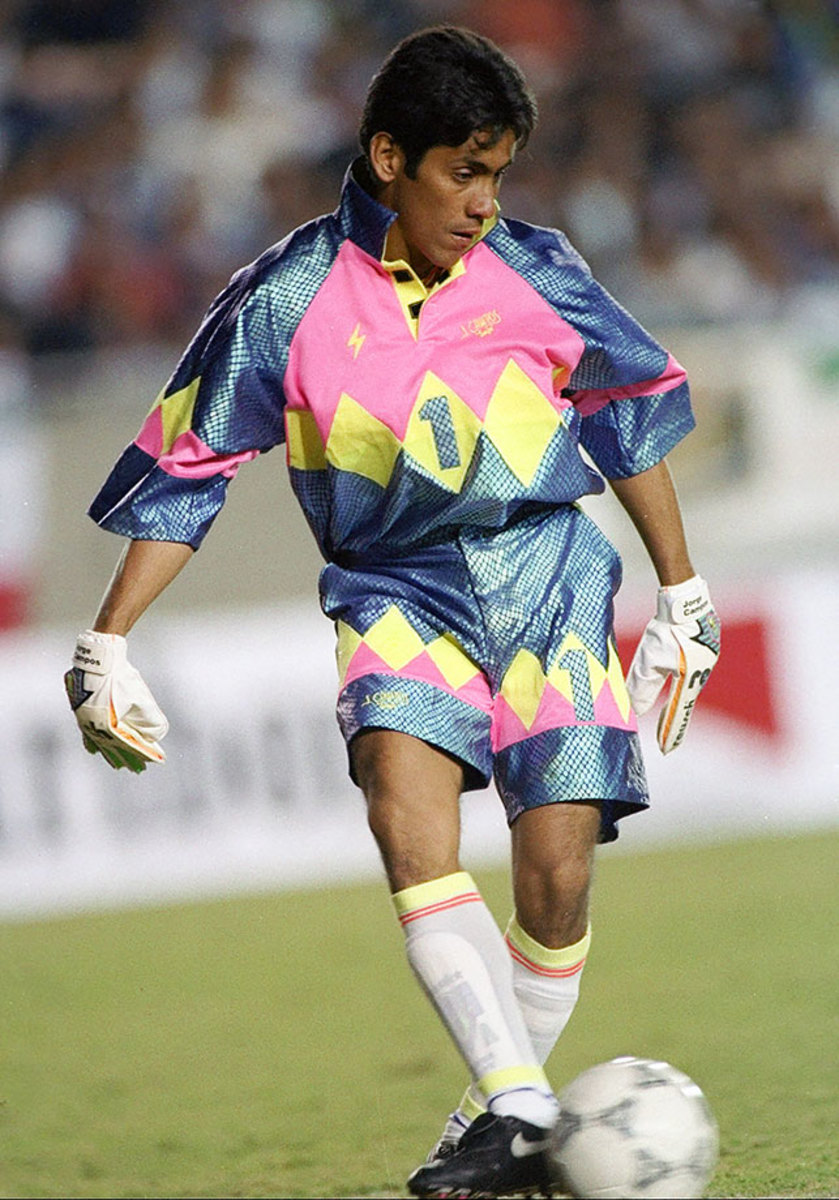

“It was a special position,” he says of the freedom he was given to freestyle. “Now it is more—I don’t know how to say . . . it’s more strict. Midfield, defense, right, left, center.” As if his playing style weren’t revolutionary enough, Campos seized our sartorial imaginations by donning uniforms—baggy surf shorts and oversized polo shirts, collar always turned up—that looked as if Montezuma had eaten radioactive tacos before ejecting his fluorescent revenge into Campos’s locker.

Jorge Campos’s most eclectic uniforms

Jorge Campos' Most Eclectic Uniforms

“I’m from Acapulco,” Campos explains, resting for a minute in an airport coffee shop. “The beach, surfing—I didn’t get to the ocean every day [growing up] . . . But every weekend? Definitely. So I was thinking: If I can’t surf anymore, I’ll bring the style, the shore, the coloring, to soccer.

“Kids loved it. They didn’t [care] if I played well or not.” Another laugh, leaning back in his chair. “I never thought it was going to be as big or marketable [as it became]. It was a big business for someone other than me. There was a lot of”—grinning, seeking the right word—“imitación.”

A lesser man might be bitter about the lack of remuneration he received for revolutionizing goalie apparel worldwide, but Campos genuinely doesn’t seem to understand the adjective “bitter”. He just unfurls another childlike laugh—eyes closing, crow’s feet deepening—warming his corner of the deserted terminal.

Technically, Campos’s residence is in L.A., but he concedes that “home is everywhere. With my job I have to fly a lot to Mexico. When I retired I decided to move to L.A. because I played for Galaxy—did you know that?” Yes, I knew that.Just like every other sports fan above 25 in this city of 13 million. “After Galaxy, I was an assistant coach with the [Mexican] national team. I thought: O.K., maybe in the future—eight years, 10 years—I can be head coach for the national team.” But when coach Ricardo La Volpe was fired, Campos learned that “in Mexico, when they change the coach they change everything.” A big laugh. “So somebody invited me to work at Azteca.”

• The Birth of a League: An oral history of MLS’s inaugural 1996 season

Campos’s style on the air is as lively and unpredictable as his netminding once was. His soccer insights are sharp but his chemistry with hosts Luis García Postigo and Christian Martinoli (who jokingly calls him George Fields) is what makes the broadcasts work. “We have fun when we do games,” Campos says. “I like that. I need it to be that way.”

Sportortas, the Mexican fast-food chain he started with his brother, Miguel, closed its American locations a few years back, so it’s not as if Campos’s schedule is packed. So what does he do now when he isn’t broadcasting or flying to work? “You see my bag, right?” he says, nodding toward a quiver of high-end golf clubs, laughing his biggest laugh yet, because who would have predicted it? “I play a lot. I practice every day. When I retired, a friend said, ‘You have to do something different. You retired young.’ [He played his last game at 37.] I realized: I can do anything. I can play golf anywhere I travel. So I enjoy it. I have fun.”

Campos says he promised himself as a young man that he would only play soccer for as long as he was willing to work at it. “If you want to do something you have to do it with passion. Soccer for me was a passion. Every day. Every year. All the time. Then one day I started to practice golf . . . Then I started to practice like a professional.” Campos, who admits that testing his five handicap on the pro tour in Mexico has crossed his mind, shows the stranger his phone with its screensaver picturing Tiger Woods crushing a drive in his red-and-black Sunday best. For all of Woods’s personal shortcomings, Campos says, “you must remember that this man practiced every day.”

Campos relaxes beneath the terminal’s harsh lights and starts talking about the game that shaped him. He starts with flopping. “People say we have to have a camera [at the goal] so we can see if it’s a goal or not. I say: No, we have to have a camera for players faking fouls so we can say, ‘See that guy? Two games—out.’ The next game he won’t try anything. We need to teach the players respect for this game.”

On U.S. Soccer: “The [men’s] team—I have to say it’s better than Mexico’s. Mexico is good, but [the U.S.] do more than us in the World Cup. They’ve gone to the quarterfinals. We have never done that. I think they have a chance to go to the semifinal or final [in 2018].” This enthusiasm he attributes to the sport’s ever-growing popularity in the States, where he sees it being played every time he drives through L.A. “Instead of [American] football, they play soccer. On a baseball field—everybody’s playing soccer! Everywhere. When I came here in 1996, to MLS, there were 10 teams. Every three months we’d play the same team two times. Now it’s a real league. They grew up fast.” He remembers a young MLS official named Sunil Gulati assuring him, against all precedent, that soccer in America was a fast-ripening fruit. Today, one of the first foreign players to sign with MLS accepts no credit for inspiring legions of young American goalkeepers to don their neon and take up the game. “No, no,” Campos says. “Sunil and all the guys who worked with him, they’re responsible.”

Campos politely declines to talk about his family, most likely because his father—his boyhood coach and best friend—was kidnapped in 1999 from an Acapulco park named after Jorge. (Alvaro Campos was held for ransom for six days before being freed; he died in 2013.) This brush with darkness would help explain why the younger Campos craves both anonymity and fellowship these days, why he wants to love the people more than they love him. Campos can walk around unnoticed in the States far easier than in his home country. Ever playful, he delights in messing with those who spot him, wherever they are. “They go, ‘Are you Jorge?’ ‘What?’ ‘You look like Jorge.’ ‘Nah, I hear that a lot.’ ” More laughter rockets off of LAX’s stone walls.

“I play golf with guys and they ask, ‘What do you do for work?’ I say, ‘I work in soccer.’ They say, ‘Did you play?’ ‘Eh, a long time ago.’ ” Not so long ago, though, that he couldn’t place a diving header in the back of the opposing net in a Mexican legends game in May.

When someone is certain they have recognized his smirk or his espresso-colored eyes, “that’s when I say, ‘Me? You think I play goalie? But goalies are’ ”—he raises one hand here, indicating tallness. “They give up and say, ‘Yeah, you’re too short. Too skinny.’ ”

Kids today don’t recognize him at all, which means that Campos often finds himself standing and waiting while parents cue up grainy videos on their phones—and here Campos admits he has seen small eyes light with glee. “This makes me feel wonderful,” he says. “It’s nice when kids see the fun you can have in this game.”

• From the Vault (1994): Jorge Campos, Mexico’s unique ‘Goaltender/Forward’

The legend remains a fan himself. “I like to watch [Manuel] Neuer, from Bayern. I think he’s the best goalie in the world. He’s amazing.” Yet only a keeper with Campos’s on-field wanderlust could admit that Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, Neymar and Iniesta are his favorite players.

On the subject of his own legacy, Campos is more reticent. He doesn’t want to be remembered for his Day-glo jerseys or his shocking forays to the other side. “I’d like people to remember me for playing for the national team—defending the colors, the Mexican jersey. This for me was the most important moment.” Chin on his chest now, traveling back in time as the announcement comes that his flight is about to board, he says, “I remember Estadio Azteca, the screaming: ‘Mexico! Mexico!’ That moment is . . . incredible.”

With that, the Acapulcan sprite who took the game of soccer into his goalie-gloved hands and squeezed it until it oozed between his fingers—into arcs the shape of his goal-thwarting leaps, the shape of his sidewinding journeys down the pitch—rises, shakes the stranger’s hand, offers the tiniest bow and makes a gentleman’s exit.

Who knows, Campos may yet monetize the goalkeeping fashion craze he started 25 years ago. He has trademarked his name, he says, “and I may to try to do something in the future, maybe clothes for everyday—or for golf. Maybe I can design something for a team or for a goalie that’s different. But it’s hard. Today’s goalies have to use the same brand their teams wear. It’s not like in my time. I did whatever I wanted.”