Bayern Munich's Mr. Cool: Xabi Alonso on being a midfield metronome

This is the fourth in a series called Total Fútbol, a soccer take on George Will's Men at Work, which analyzed an expert at different positions in baseball. To translate it to soccer, SI has interviewed, in great detail, a goalkeeper (Manuel Neuer), defender (Vincent Kompany), midfielder (Xabi Alonso) and forward (Javier "Chicharito" Hernandez) in regards to how they go about their craft. This the game through Alonso's eyes.

This story first appeared in the June 22, 2016, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

He is soccer’sanswer to George Clooney, a midfielder so cool and self-assured that you can imagine him playing the game in a tuxedo, perhaps while carrying a gin and tonic. "Desperation" is not a word in Xabi Alonso’s vocabulary, which is why he thinks the elaborate midfield slide tackle—that bastion of English-style bustling commitment—is overrated. For what is a slide tackle, Alonso reasons, if not an admission that your positioning could have been better?

“Especially in the U.K., some people understand—and some people don’t,” says the World Cup–winning Basque Spaniard who has played for such storied clubs as Liverpool, Real Madrid and now Bayern Munich. “If you are too much on the ground, then something is not right. I love good tackling, but I prefer the player who does not need to do that.”

The methods behind Manuel Neuer's sweeper-keeper madness

At 34, with an almost unmatched understanding of the game, Alonso is one of the defining two-way midfielders of his generation. He has worked under some of the sport’s premier managers—Carlo Ancelotti, Vicente del Bosque, José Mourinho, Rafa Benítez—but in 2014 he joined Bayern Munich with the intention of preparing for his own coaching career by immersing himself in the methods of Pep Guardiola.

“I learned a lot these two years,” says Alonso, who’ll stay in Munich next season under Ancelotti as Guardiola moves to Manchester City. “[It was] very useful for me to understand more about football and how I want to do things.”

Wearing a black Mr. Rogers–style cardigan over a plain gray T-shirt, Alonso settles into a meeting room at Bayern’s training ground and spends nearly an hour unpacking the duties of a central midfielder in 2016.

“You cannot relax; you have to be always on your toes,” Alonso says. “It’s not like a striker; they can afford 30 seconds [of rest] when they aren’t involved. Midfielders have to be fully concentrated during the 90 minutes to be in the right place.”

Alonso is obsessed with positioning, movement and space. Surprisingly, he says he has learned almost nothing new about how to pass the ball since he was an 18-year-old at Real Sociedad, in La Liga. A natural distributor, he has always been able to hit any type of pass, from short tiki-taka touches to piercing through-balls on the counterattack to 40-yard diagonal Hollywood passes.

“That’s never been the hard part for me,” Alonso says. “But maybe I couldn’t position myself as well as I do now.” That location education continues even today, accelerated by two years of studying Guardiola’s constantly shape-shifting tactical approaches.

What's Belgium missing at Euro 2016? In Kompany, a center back rock

Does Alonso touch the ball a lot? You’d better believe it. During the 2015–16 Bundesliga season he averaged 108.4 completed passes per 90 minutes for a remarkable 91% success rate, according to Opta. But his gigantic influence on a match is less about making killer passes than about controlling the play with a critical mass of small choices—thousands of them, 90 minutes at a time. They are the essence of a two-way midfielder.

“It’s all about balance, about making a lot of right decisions,” Alonso says. “Maybe they look unmeaningful [individually], but putting all of them together, they make sense. My job is not to make spectacular actions. Maybe that happens once in awhile, but that’s not my job.”

What is Alonso’s job? Well, that depends on whether or not his team has the ball.

**********

The variety ofattacking methods on Alonso’s teams over the years has been remarkable. His Liverpool team won the 2005 Champions League crown with a dynamic quick-strike capability that employed Steven Gerrard at the height of his powers. When Spain won World Cup ’10, it suffocated opponents like a python with short passes and maximum possession.

Alonso’s Real Madrid raised the ’14 Champions League trophy largely by funneling the ball to the ultimate avatar of whooshing athleticism, Cristiano Ronaldo. And if Alonso were to win his third Champions League title with yet another team—matching the record set by Clarence Seedorf—it would be on a Bayern Munich outfit that combines ball control with the ability to pounce on the break.

Each approach has been different, yet Alonso’s basic role when his team owns possession has stayed the same.

“When we win the ball, my job is to get it from the defense to the attackers in the best possible way,” he says, “[so they can] go one-on-one or have a good position to make the last pass. You won’t see me like [Real Madrid midfielder] Luka Modric, dribbling through guys. That’s hard for me. The pass—that is more natural for me.”

GALLERY: Bayern Munich takes on Oktoberfest

Bayern Munich at Oktoberfest

Bayern Munich

Pep Guardiola and wife Cristina

Pep Guardiola and wife Cristina

Robert Lewandowski and wife Anna

Robert Lewandowski and wife Anna

Robert Lewandowski and wife Anna

Robert Lewandowski and wife Anna

Thomas Müller and wife Lisa

Thomas Müller and wife Lisa

Thomas Müller

Thomas Müller and wife Lisa

Xabi Alonso and wife Nagore

Xabi Alonso and wife Nagore

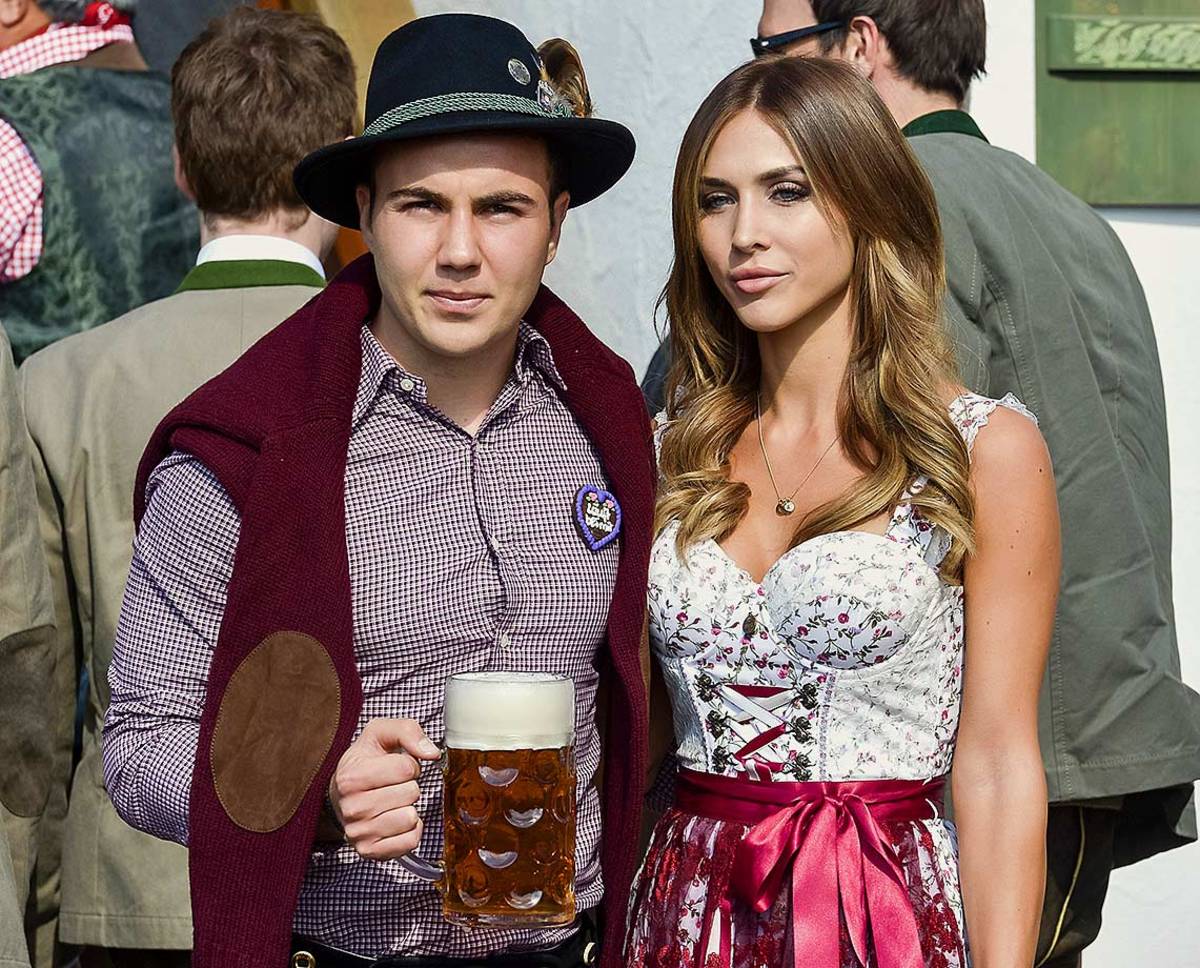

Mario Götze and Ann Kathrin Broemmel

Mario Götze and Ann Kathrin Broemmel

Thiago and Julia Vigas

Thiago and Julia Vigas

Rafinha and wife Carolina

Arjen Robben, Arturo Vidal and Rafinha

Medhi Benatia, Franck Ribery, Jerome Boateng, Kingsley Coman and David Alaba

Thomas Müller

Douglas Costa

Douglas Costa

Juan Bernart and Javier Martinez

Juan Bernart

David Alaba and Katja Butylina

Arturo Vidal

Arturo Vidal

Arturo Vidal

Douglas Costa

Douglas Costa

Philipp Lahm, wife Claudia and son Julian

Philipp Lahm, wife Claudia and son Julian

Kingsley Coman, Douglas Costa, Medhi Benatia and Franck Ribery

Team President Karl Hopfner and wife Anne

CEO Karl-Heinz Rummenigge

Before Alonso can deliver a pass, though, he has to receive the ball. And before he can receive the ball, he has to be aware of what’s surrounding him from a 360-degree perspective. The only way to do that is by constantly swiveling his head and employing his peripheral vision to register players (teammates and opponents) and open space. “I have never seen a [video], for the full 90 minutes, just on me,” he says, “but I would be curious to see if I am always”—here he pantomimes darting his gaze in different directions, like a quarterback scanning the defensive secondary.

Inside the churning mind of Mexico's Javier ‘Chicharito’ Hernandez

In modern soccer, defenders close down space in an instant, all over the field, which is why you have to map out the surrounding terrain in your mind’s eye before they bear down on you.

“Before receiving the pass, I try to have an idea of what’s going to be the next decision,” Alonso says. “When you get the ball, it’s probably too late, because you will have the opponent on top of you.”

But completing a pass isn’t just about picking a target and sending the ball to your teammate. Alonso says he takes into account the weight and distance of the pass, the location of defenders, the preferences of the player receiving the ball and whether Alonso is passing to feet or to space, on the ground or in the air.

“When I make a pass, my goal is for [my teammate] to have the best possible way, on the right foot or left foot, to have an advantage,” he says. “Of course, [my teammate] has to be in the right position. That’s his job. But, for example, if I pass to the left, he may have more problems to turn, so I pass to his right foot. That’s my idea: to create a pass with an advantage, not to create a problem.”

Italy dominant, special in ousting reigning Euro champion Spain

Because Alonso touches the ball so often in any given possession, he can influence the tempo of his team’s passes, adjusting the metronome to a higher frequency to put pressure on the opposition, or to a lower frequency to settle the game down. Throughout, risk management is always on his mind. When you’re closer to the goal in the attacking end, he says, you should take passing risks, because one good pass can turn into a goal.

But in your own end a risk would be foolish and could result in the ball finding your own net.

Even when Alonso’s side has possession, he’s thinking about his teammates’ collective shape should a turnover occur.

“When the strikers are attacking,” he says, “I have to think: If they lose the ball, where should I be positioned to regain it as quickly as possible? Sometimes, depending on your position, you need to press high. But if you’re more exposed, you need to take a step back and try to defend the space rather than the man. You need to distinguish those moments.”

That discerning power is part of what Alonso has studied so closely under Guardiola. During the game, however, it can’t come from a coach. It has to be internal.

**********

Alonso pressesplay on a laptop. On the screen: a Champions League group-stage match, Bayern Munich hosting Arsenal, from last November. Bayern had lost 2–0 to Arsenal two weeks earlier, and Alonso says preparations for this game—mostly through video study—were as intense as ever under Guardiola.

Prepping for Pep: Who stays, goes at Manchester City?

The clips the coach showed were focused on Arsenal as a team, Alonso explains, but “you can ask for video of the players around your position. For example, I know [Gunners midfielder] Mesut Özil pretty well [from their time together at Real Madrid], but I didn’t know as well how he was playing with his Arsenal teammates. When he was playing to Theo Walcott, he would play more to the space [in front of Walcott].”

Similarly, Alonso studied Arsenal’s Alexis Sánchez. “Some wingers, they close in to the middle,” he says, “and if they close in, there will be space outside. We know that Alexis has more of a striker’s mentality, so he will leave open the space between the central midfield and the winger. That’s the position we wanted to exploit.”

Sure enough, Bayern’s first two goals come from crosses in which Arsenal—not just Sánchez—fails to put pressure on a passer positioned out wide. By halftime it’s a 3–0 blowout, and Bayern is dominating possession. Alonso’s distribution is impeccable, a kind of Chinese water torture: mostly short passes with the occasional long-distance arrow.

Germany's Low pushing right buttons with Gomez, Draxler, Kimmich

Why short passes? So much of the modern game is about transitions, the decisive moments in which possession is lost and the team that has won the ball can advance on a foe that’s slightly unbalanced or disorganized. In most cases, Alonso says, he’d prefer that his team make two or three short passes rather than one long pass, the better to keep his teammates in a compact shape, ready to defend as a unit should they lose the ball.

“When you’re playing long passes, your players have much more distance between each other,” Alonso explains, “and when they lose the ball, it’s harder to get the ball back because they can’t pressure as well together.”

How you attack and how you defend—those are inextricably linked, and no player is more responsible for a team’s combined approach than a two-way midfielder such as Alonso. Against Arsenal he is in complete control, at the center of everything, like a conductor whose symphony surrounds him on all sides. When Bayern finishes off its 5–1 victory, it’s hard to remember a single play that Alonso made. Yet in his own way he was the most dominant player of the game.