The best World Cup format–that FIFA would never consider

The World Cup might grow to 40 teams, or it might wind up with 48. It might be eight groups of five or four groups of 10, or there might be 16 seeds and a straight 32-team knockout round to get to join them in the format we have now. Or it might be 16 groups of three.

Either way, the endless gigantism stimulated by FIFA presidential elections, as candidates promise more and more nations that they, too, can play in a World Cup, means that the competition will be even more bloated, even more unwieldy by then. Of course, this is 2026 we’re talking about, so there’s a significant chance global political elections by then will mean that by then, as George Orwell foresaw, it’s just three teams: Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia.

The format Gianni Infantino let it be known that he prefers is 16 groups of three, with the top two going through into a round of 32. From there, it would be a straight knockout competition. It would mean an increase to just 80 games from the present 64, so it could still be completed in around five weeks, while the winners would still, as of now, have to play seven games–something that’s important in not antagonizing the clubs who actually pay the players.

Roundtable: What's the best format for an expanded World Cup?

But there are significant problems with the proposal. For one thing, each team would be guaranteed just two games rather than the three they are now. But then–and this tends to be the last issue considered–there’s a question of sporting integrity. The fixtures would run A vs. B, A vs. C, B vs. C. B has a clear advantage, because it would have a longer rest between matches–not a day or two as sometimes happens now, and is all but unavoidable, but three or four days.

Or what if A loses the first two games? Then the third game would be a dead rubber (although that could be avoided by having A vs. B followed by C vs. the winner of the first game, followed by C vs. the loser of the first game. This complication to the scheduling is just about manageable so long as a group is, unlike now, played in a single venue rather than spread around to make sure as many cities as possible in the host nation get to host the "glamorous" countries).

It’s true there may be an advantage in topping the group and playing a second-placed team in the next round, but this wouldn’t be a free draw like, say, the Champions League, in which probabilities rule and, even if a giant finishes second in its group, you’re still more likely to get a straightforward game by coming out on top. If it were anything like the present format, the team topping Group F, for example, would know it faces the runner-up in Group E. And it’s easy to imagine a situation, if Group E finished first, in which coming second was preferable for teams in Group F, making that third group game worse than a dead rubber–it would be one that both sides want to lose.

Or imagine the first two games in the group finish 0-0. A 1-1 draw in the third game then takes both teams through. Even if there were not direct collusion, is any side going to rock the boat if they find themselves at 1-1 with half an hour to go? And what if all three games finished 1-1–or any of the various other highly possible combinations of scorelines that would leave all three sides equal? What, then, is the tiebreaker?

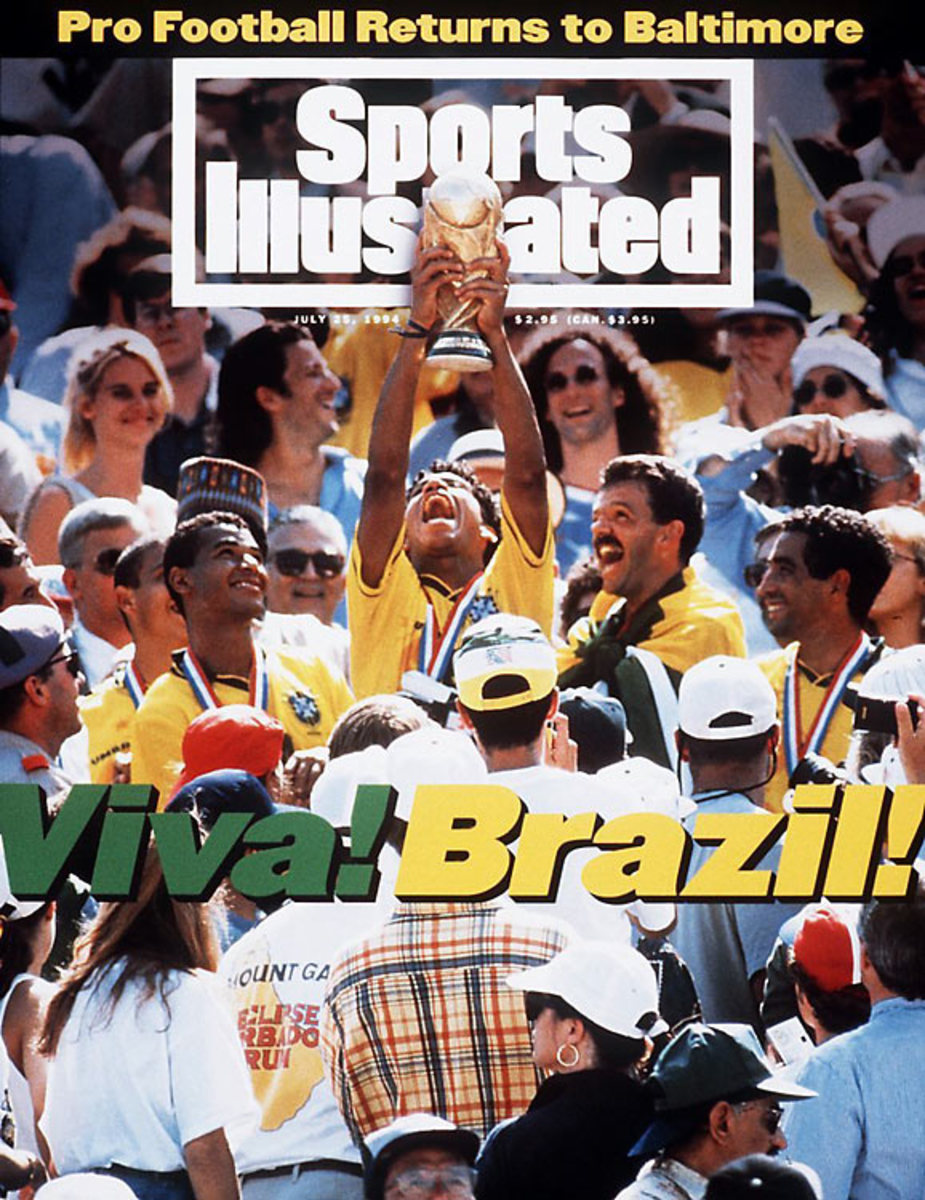

GALLERY: A history of World Cup winners

World Cup Winners

1930: Uruguay

The hosts won the first World Cup, beating Argentina 4-2 in the final. Uruguay's victory in the 13-team tournament was the start of a trend: The host nation has won six of 18 World Cups, and even lesser sides that have hosted usually have exceeded expectations.

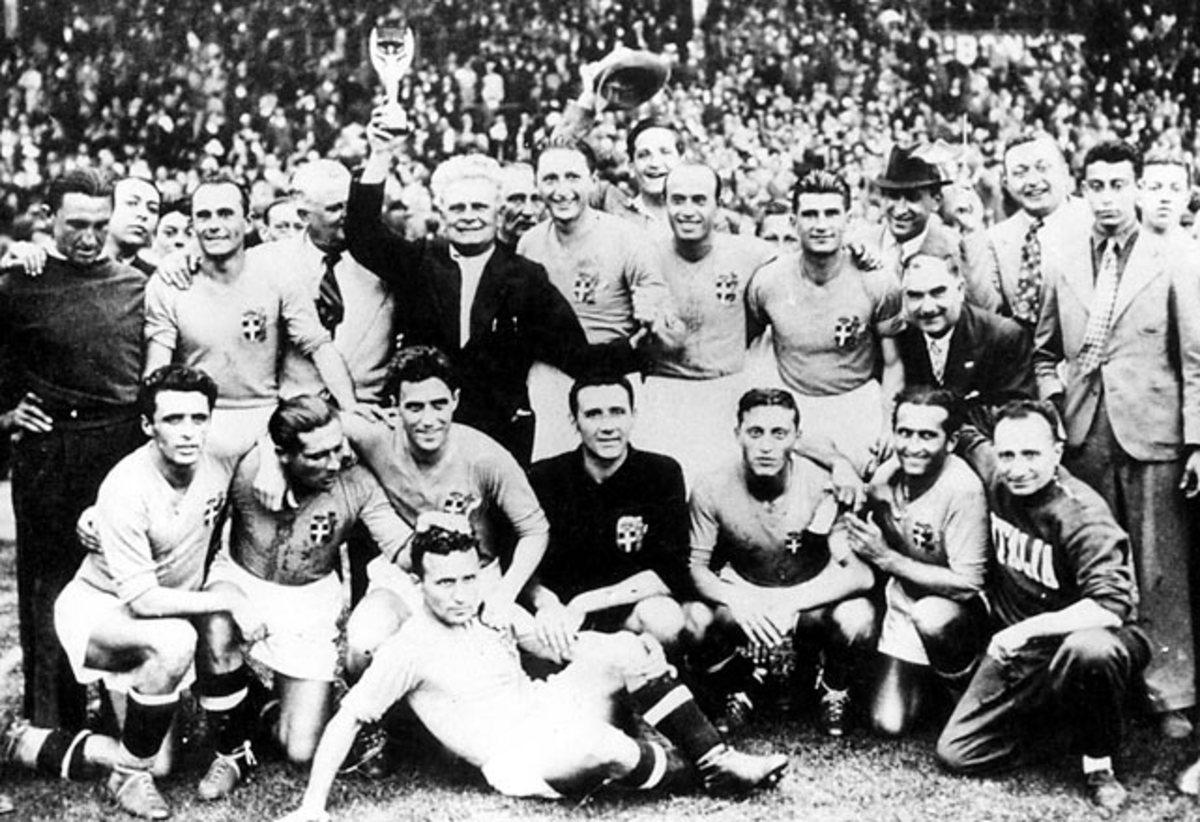

1934: Italy

The host nation delivered again as Italy beat Czechoslovakia 2-1 in the final thanks to an extra-time goal from Angelo Schiavo. The Italians had opened the tournament with a 7-1 rout of the United States before beating Spain and Australia en route to the final.

1938: Italy

Italy won its second consecutive World Cup behind striker Silvo Piola, who scored twice and set up another goal in a 4-2 victory over Hungary in the final. The tournament included Brazil's epic 6-5 win over Poland in the first round in which Ernest Wilimowski scored four goals in a losing effort and Leonidas countered with a hat trick.

1950: Uruguay

While the United States pulled off the shocker of the competition by beating England, Uruguay joined Italy as two-time World Cup winners. Alcides Ghiggia scored in every game for Uruguay, including the game-winner in the final against host Brazil.

1954: West Germany

West Germany lost 8-3 to Hungary in the second game of the tournament, but exacted revenge in the final when it overcame an early two-goal deficit to win 3-2. This was the highest-scoring World Cup in history (5.38 goals-per-game average), with Hungary accounting for 26 in five games.

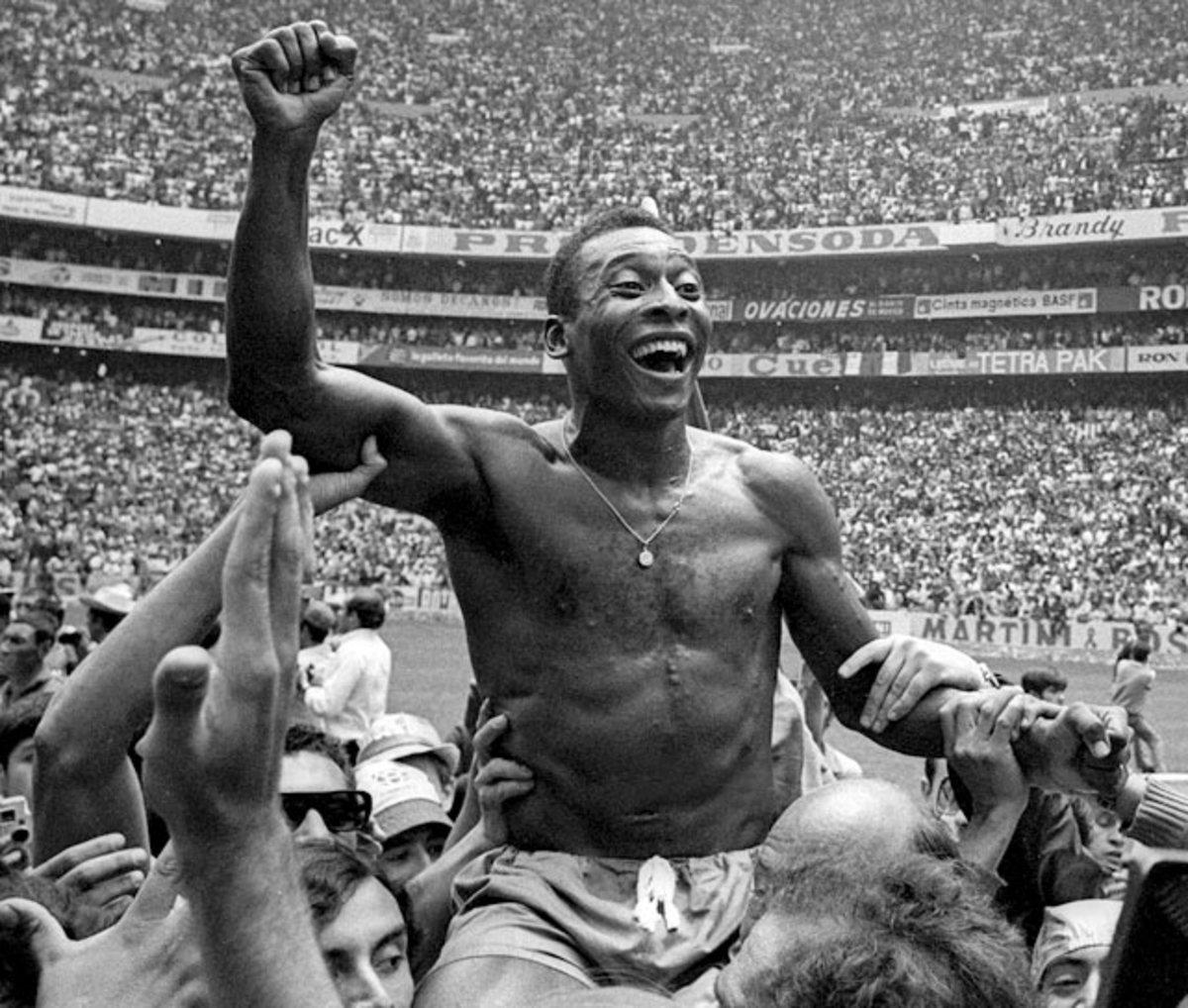

1958: Brazil

The first internationally televised World Cup gave us Brazil's Samba soccer and 17-year-old sensation Pele, who scored six goals in the tournament. It also provided the first winner outside its home continent, Brazil, which defeated host Sweden 5-2 in the final.

1962: Brazil

Despite the loss of Pele to injury, the Brazilians looked as dazzling as ever, overwhelming Chile 4-2 in the semifinal. The Czechs put up more of a fight in the final, but were overcome by two second-half goals as the Brazilians repeated as champions.

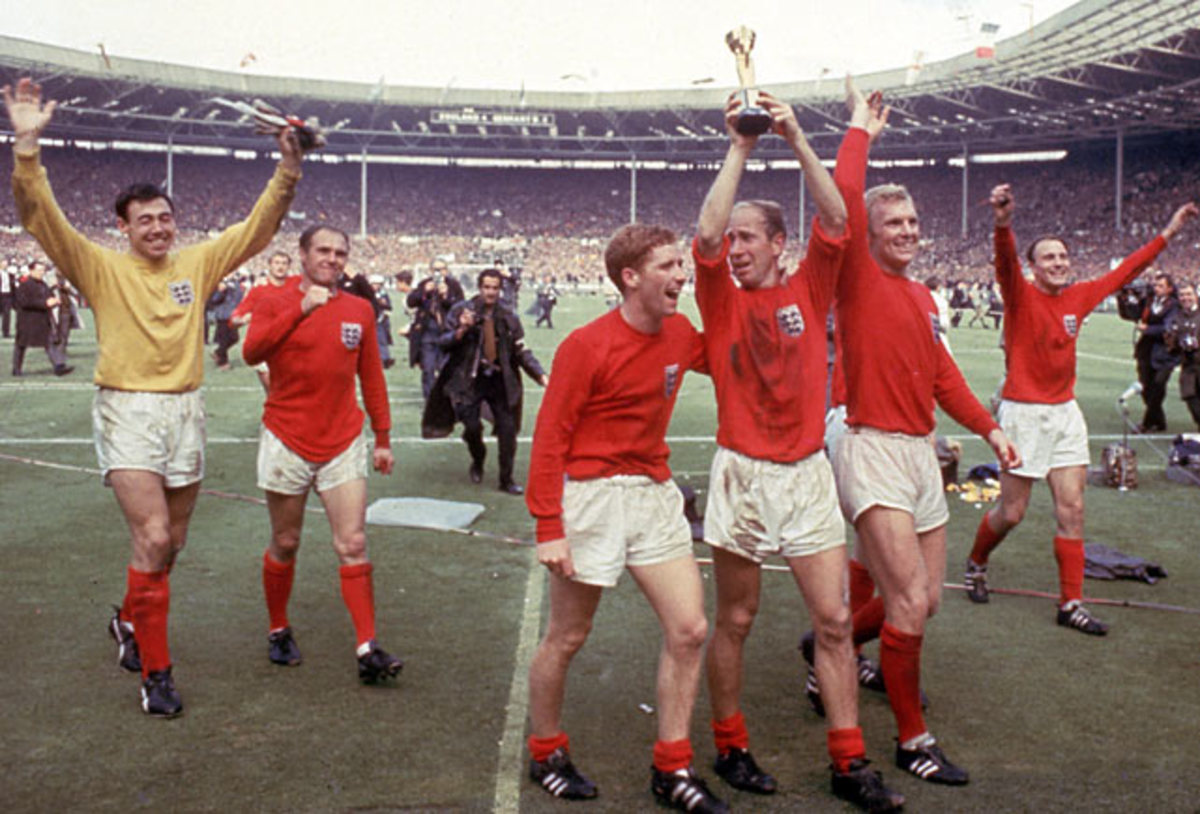

1966: England

England triumphed on home soil under Alf Ramsey, who'd revolutionized the national team. The 4-2 win over West Germany after extra time in the final remains the defining moment in English soccer, though the containment of Portugal a game earlier was equally decisive.

1970: Brazil

Brazil's free-scoring run through the rounds, a scintillating semifinal between Italy and Germany and Gordon Banks' "save of the century" against Pele in Brazil's classic group victory over England helped make this what is widely viewed as the best World Cup ever. Brazil downed Italy 4-1 in the final.

1974: West Germany

Led by Sepp Maier, Franz Beckenbauer and Gerd Müller, West Germany overcame a classy Dutch side in the final to win the title on home soil.

1978: Argentina

The first World Cup in Argentina ended with a fifth title for a host nation. Mario Kempes won the Golden Boot with six goals, including two (to go with one assist) in Argentina's 3-1 victory over the Netherlands in the final. This was Holland's second consecutive loss in a World Cup final.

1982: Italy

In the first 24-team finals (eight more than in '78), Italy unexpectedly matched Brazil with its third title. West Germany and Brazil were the favorites and both won every game in qualifying, but Italy, led by Paolo Rossi, who had recently returned from a match-fixing suspension, knocked off both en route to victory.

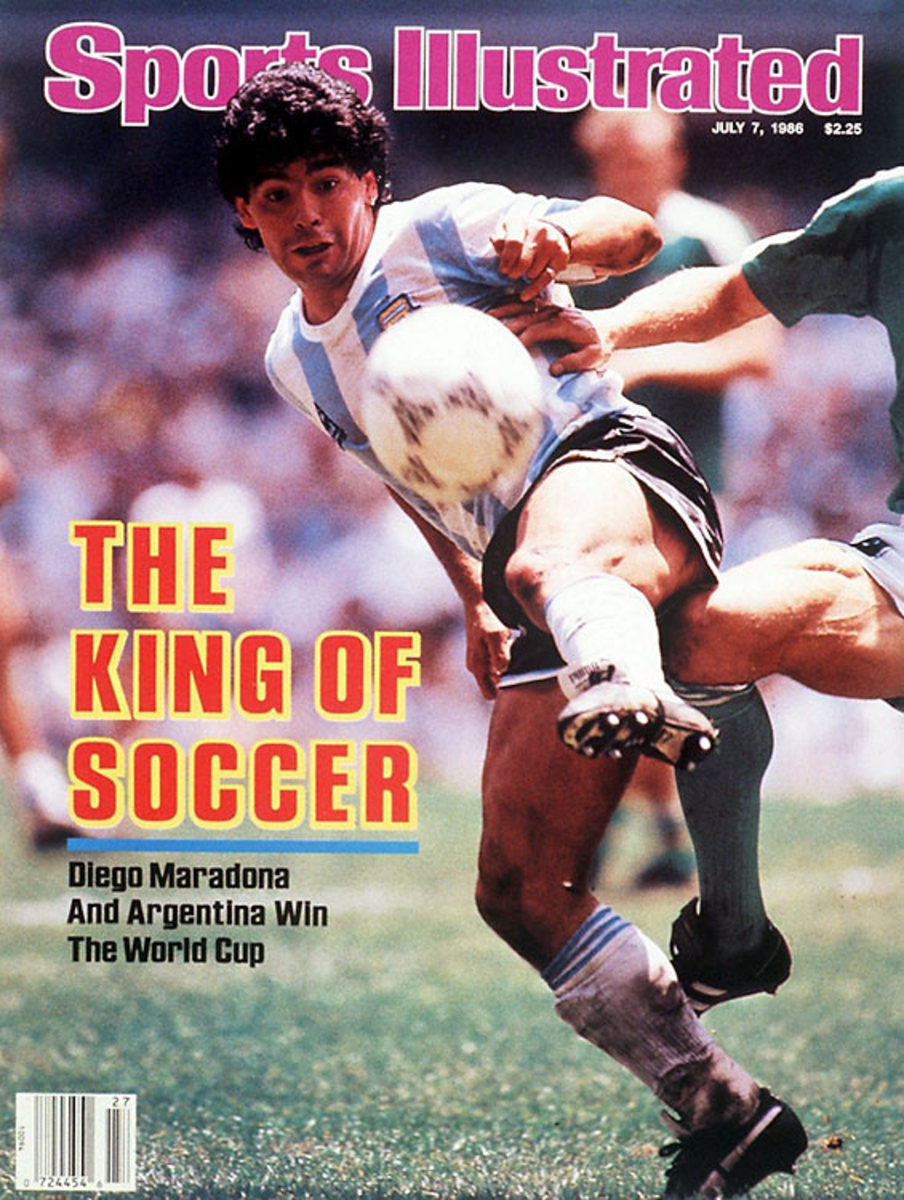

1986: Argentina

Maradona owned the 1986 finals in Mexico, playing with fearlessness and guile–and a little luck, too, as his Hand of God goal helped Argentina slip past England in the quarterfinals. His performance against Belgium in the semis (two second-half goals) was incredible, and though the Germans kept him quiet for most of the final, it was his cross that set up Jorge Barruchaga for the winner.

1990: West Germany

In a rematch of the '86 final, West Germany got the best of Argentina 1-0 in a physical match (an appropriate finish to a rough-and-tumble tournament short on goals) in Italy.

1994: Brazil

Brazil and Italy played a mediocre final in the first tournament hosted by the United States, with the Brazilians winning in a penalty shootout after a 0-0 finish following extra time. Brazil became the World Cup's first four-time winner.

1998: France

France came back from a goal down against Croatia in the semifinal to set up its first final appearance, against Brazil. Rumors abounded that Ronaldo suffered a fit immediately before the match, but host France deserved its win after completely dominating the match thanks to two first-half headers from Zinedine Zidane.

2002: Brazil

Japan and South Korea became the World Cup's first co-hosts, and the first in Asia, and they produced a tournament full of surprises, if not amazing soccer from the usual suspects. The unexpected success of newcomer Senegal, as well as Turkey, the United States and South Korea, added to the novelty of the event. In the end, though, the final was contested between old faces Brazil and Germany, despite the relative weakness of their lineups. Ronaldo scored both goals in Brazil's 2-0 victory.

2006: Italy

Italy went unbeaten in the group stages and was then inconsistent through the knockouts, but deservedly took an extra-time victory over host Germany in the semis before beating France on penalties in the final. The French had started to dominate into extra time, but Zinedane Zidane's headbutt on Marco Materazzi left it a man down, and David Trezeguet's missed penalty handed Italy a fourth World Cup.

2010: Spain

Spain capped its golden era with a World Cup triumph, following its Euro 2008 title with another on the grand stage. Andres Iniesta's goal in extra time of a physical final led Spain over the Netherlands and allowed La Furia Roja to lift the trophy.

2014: Germany

Germany's run concluded with an extra-time triumph over Lionel Messi's Argentina, with Mario Gotze supplying a sensational winner to crown the Germans once again.

But this comes back to something far more fundamental. What is a World Cup for? It already feels overlong, with too many drab games that are essentially moderately well-drilled defenses against attacks that at the club level would take them apart but at the national level lack the slickness that comes with months of playing together and developing a mutual understanding.

When Germany won the World Cup in 2014, how many games did it play against sides that might potentially have won the tournament? Three? Four? Spain in 2010 arguably played only two, three at most. Often the group stage feels like a protracted throat-clearing before the main event. If the World Cup were just about the best against the best, determining the top side in the world, it would make sense to return to the system of 16 teams in four groups of four leading to quarterfinals that existed between 1958 and 1970.

But the World Cup is about more than that. It’s about global representation and trying to grow the game in developing football countries. The present 32-team structure, flawed as it is, probably does offer the best balance between those aims unless FIFA were prepared to accept something truly radical.

There is a way to both spread the reach of the game, and concentrate quality so it became again a festival of the best playing the best.

Jurgen Klinsmann leaves behind a complex, unfulfilled U.S. Soccer legacy

Imagine this: a host is selected for a 16-team finals, the reduction to a 32-game competition lessening the demands on the hosts and so opening up the possibility of hosting to far more countries. The other 15 teams then come from a global qualifying competition of, say, 60 teams.

Those 60 teams would be determined from regional pre-qualifying. Roughly doubling the present allocation to the 32-team World Cup, that would mean, say, 22 sides from Europe, 14 from the Americas, 12 from Africa and 12 from Asia/Oceania. Divide them into 15 groups of four and play home and away with either the top side going through or the top two going through into a knockout, home-and-away playoff round.

So a possible group may be France, USA, Algeria and Japan; or England, Chile, Burkina Faso and Iran; or Slovenia, Argentina, Ghana and Australia. What is better for the game in developing football nations? Playing three games in a distant World Cup, or hosting three major games in your own country where substantial numbers of your own fans can actually go and watch? And for developed nations, traveling to other continents would alleviate the familiar plod around teams within your own confederation.

If that meant the final 16 included a dozen European nations or 10 from the Americas, so be it: they’d have earned their right to be there. Sport is about about winning and about offering the chance to compete. This provides both.

It won’t happen, of course. There are far too many vested interests in the present structure. What might actually be good for football is the last thing that will be taken into account, and so we trot on, diluting the World Cup further and further because that might bring votes in a future presidential election, leaving a once great tournament defiled by greed and political expediency.