The Complications Surrounding the Copa Libertadores Final Unlike Any Other

The second leg of the Copa Libertadores final, we are told, will happen. Or at least that’s what CONMEBOL insisted at a meeting in Asuncion, Paraguay, on Tuesday.

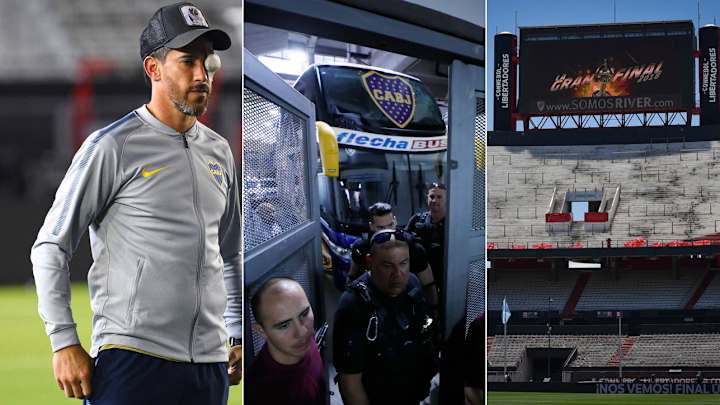

The second leg, postponed from Saturday to Sunday after an attack by River Plate fans on the Boca Juniors team bus, and then again after it was decided Boca’s players were in no state to play, is now scheduled to take place on either Dec. 8 or 9. Where it will be, CONMEBOL remains unsure, other than that it will not be in Argentina. A number of cities have emerged as potential venues, including Asuncion, Miami, Genoa, and Abu Dhabi. Yet there must be some doubt as to whether the game is played at all, given Boca remains determined it should be awarded the title.

None of these issues are straightforward, but let’s deal with them in order of ease. First, the when. If it is to be played, the match must be staged before Dec. 10, because the winner of the tie will play in the Club World Cup, which begins in the UAE Dec. 12. With the G20 summit beginning in Buenos Aires on Thursday, it could not be held in Argentina until that is over, and any other venue would require time to prepare. Realistically, that weekend of Dec. 8-9 is the only available date.

The where is more controversial. The claims of Argentinians that the game must be played in Argentina can be dismissed. They had their chance and failed. The safety of players, officials and fans must be paramount. More troubling, though, is the precedent. If this game can be played in different continent, what does that mean for FIFA's insistence that, for example, La Liga cannot play a game in the U.S., that matches must be played in the “right” country or continent? That said, these are exceptional circumstances.

But the trickiest issue is whether the game should be played at all. Daniel Angelici, the president of Boca, believes his side should be awarded the game by walkover and has threatened all manners of legal action if CONMEBOL demands the game be played. Even over the weekend, Carlos Tevez was making comparisons with the incident in 2015 when Boca fans fired pepper spray at River players as they walked through the tunnel at La Bombonera during a Libertadores tie. On that occasion, the match was awarded to River. Why should that precedent not apply here?

WILSON: CONMEBOL Faces Questions of Leadership Amid Libertadores Fiasco

At first glance, that seems like a reasonable argument. CONMEBOL president Alejandro Dominguez had said on Friday that he was trying to separate passion from violence. Here, you may think, was his chance. Show River fans, show all fans, that pelting a bus with projectiles is not acceptable. Show them that there are consequences.

But that is too simplistic. The difference between the two incidents is clear. What happened in 2015 took place inside the stadium; Saturday’s incident took place outside. That is more than a technicality. A club must take responsibility for what happens in its own stadium. It has a duty to provide a safe environment in which the game can be played, and if it cannot do that, it must be sanctioned. Perhaps there is an argument that what happened on Saturday was so close to the stadium that the same logic should apply, but these are awkward gray areas.

The danger of saying simply that River fans did it and therefore River should be punished is that it assumes a one-to-one relationship between a club and anyone who wears its colors–and that quickly becomes an uncomfortable position. There were 70,000 River fans inside the stadium when the incident occurred on Saturday. Are they responsible for the actions of a couple dozen outside? Are the directors? Are the players?

What of the failure of policing, which many in Argentina seem to feel was related to a breakdown in the relationship between the police and the Ministry of Justice? Why did the Boca bus take the right turn into the ambush down Avenida Monroe? Or at least why hadn’t fans been cleared from the area first, as would be standard procedure? Is that River’s fault?

And even more tricky is the fact that fandom in Argentina is not straightforward. The barras bravas, the organized hooligan groups, may have started out supporting their team, but they are now interwoven with organized crime. It may be that having games abandoned, having a club face sanctions, suits the political motives of, say, somebody seeking to become president of a club. The importance such a position brings can be seen by the fact that the current president of Argentina, Mauricio Macri, used to be president of Boca, or by the way that his predecessor, Cristina Kirchner, shamelessly used football for propaganda purposes.

One of the possible explanations–and there are many–for Saturday’s events is that it was carried out because a barra leader had been arrested three days earlier. Punishing a club in such circumstances would play into the hands of those seeking to provoke embarrassment. Which is to say that the second leg probably should be played if possible and that Dec. 8 or 9 makes sense. All that remains is to decide where.