The USWNT's Partners, Allies and Disciples in the Fight for Equality

DeMaurice Smith remembers making the cold call. It was sometime in May 2017, and he’d been reading about the U.S. women’s national soccer team. At the time, the players and U.S. Soccer had just ratified a new collective bargaining agreement, which gave them everything from better travel accommodations to full control of group licensing rights. Smith had also heard about the separate wage discrimination complaint filed in March 2016 by five U.S. players with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and about players threatening to go on strike before the Rio Olympics.

Coming from his own labor paradigm with NFL players, Smith felt a kinship. This was a group of women, he thought, who were willing to sacrifice the thing they’d been working toward since they were young knowing it would benefit players who came after them.

“That’s a group of people that I wanted to be friends with,” says Smith, who has been the executive director of the NFLPA for the last decade.

And so he picked up the phone and called his women’s national soccer team counterpart, Becca Roux.

“I was like, ‘Hey, I’m De Smith and I have this job in football, but I really appreciate what you guys stand for and literally, whatever you need, you have from us,’” Smith says. “She’s representing a group of people who are getting paid less even though they win more than the men and are more popular than the men. The only reason they’re getting paid less is because they’re women. We have a huge staff, relationships across sports with apparel, licensing and marketing companies, and I told her I’m willing to bring every lever to bear to help them that I can. So that was that first call.”

Since the days of Mia Hamm, Brandi Chastain and Julie Foudy, the U.S. women’s national team has been respected for striving to advance gender equality. Players today remain committed to paying it forward because of the strong culture and sense of duty instilled back then. Even athletes in different sports—from the U.S. women’s hockey gold medalists who are boycotting playing professionally in North America, to WNBA players who recently opted out of their CBA—look to the USWNT to gain knowledge when dealing with their respective leagues and federations.

“They continuously set the market for women all over the world,” says U.S. hockey player and two-time Olympic medalist Kendall Coyne Schofield. “They are the epitome of trailblazers in a team-sport setting.”

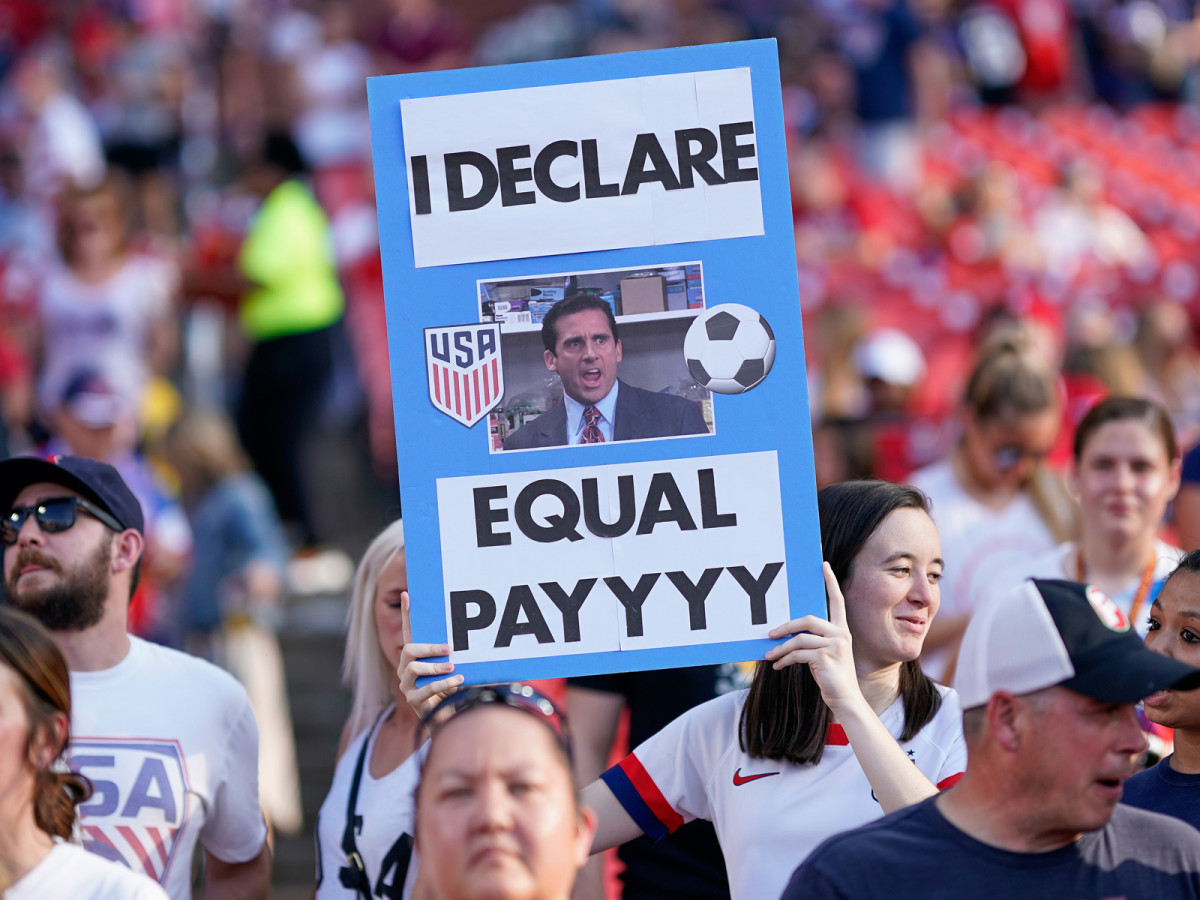

That’s one reason why on March 8—three months before the Women's World Cup and on International Women’s Day—28 players felt the responsibility to bring a gender discrimination lawsuit against U.S. Soccer.

Smith’s cold call was the beginning of a unified power movement. Just as the USWNT has been a role model for so many, it is continually striving to get smarter by using every resource available. That’s where Smith’s fortuitous friendship comes in.

“You fight uphill and then you find those people who believe,” Roux says. “And they become your advocates.”

Soccer was Roux’s first love. She grew up playing, was a national team fan, and went to the 1999 and 2015 World Cups. She was interested in having a career in sports, but ended up as a consultant at McKinsey & Co. Then after the 2015 World Cup, Roux was connected to the USWNT through what she describes as “serendipitous contacts.” The women were looking to better promote themselves after coming home from winning their third World Cup to little to no merchandise in the market. And McKinsey encouraged Roux to utilize her skillset by working with nonprofits on nights and weekends, so she started digging around the team to see how she could be helpful–and eventually set her focus to ensure the same scenario wouldn't unfold four years later.

What she found was that the USWNT players’ association didn’t have the infrastructure or connections to capture their value, despite being around since the 99ers created the group. For nearly two decades, the USWNTPA had a lawyer help negotiate a collective bargaining agreement, and that was the extent of the foundation. Before going any further, Roux challenged the players to define what they wanted to be and go from there.

“We could either be a caterpillar or a butterfly,” says Meghan Klingenberg, a starting defender on the 2015 Women's World Cup team. “We could either not have very high aspirations or we could really capture that revenue and create a structure where we can protect players.”

Despite initial skepticism regarding having a union and with Roux still needing to prove herself and earn the players’ trust, the team chose to move forward. Ultimately, the goal was to have an organization that would protect their rights, their health and safety, creating an environment for them to succeed and grow on and off the field. So after the 2016 Olympics, Klingenberg left Roux a voicemail on behalf of the team saying, “We have unanimously voted for you to come back and help us.” Roux later quit her job with McKinsey and started working for the USWNT players in February 2017, as they were in the thick of CBA negotiations.

Christen Press doesn’t even remember using the term “players association” when she first made the national team in 2013. Now she’s proud of the groundwork her teammates and Roux have laid for posterity, creating a sustainable union that’s set up to outlast one career span. Players can be as informed and as empowered as they want to be, and when new players are welcomed into the team, getting information about compensation, the history of CBA negotiations, and what’s going on within the association is easy.

“Players have all the information and access to resources that they need in order to protect themselves and feel secure,” Press says. “[They] can start to contextualize themselves in the larger scheme of things, how things should be, and where women in soccer is on the global and national stage. It gives us a huge leg up in where we are and what we can do socially for the world.”

Recognizing their place within the women’s global soccer community, U.S. players aren’t too proud to share their learnings on everything from sponsor obligations to salary with peers in other countries who may have fewer resources.

“It’s often looked at as private and you shouldn’t say anything, but it’s important to understand how the market works and to be business savvy,” Press says. “I think we’ve broken through a lot of those chains, and we’re a lot stronger together. Women everywhere are coming together fighting the same battles to be treated fairly and respectfully.”

When Roux jumped into her role full time, she quickly connected with labor unions all over the world by doing everything from attending World Players Association meetings in Switzerland to advising women’s national soccer teams from Australia, Canada, Chile and Japan.

“Any country that has a women’s team,” Roux says, “we’re trying to connect with them.”

One of her greatest resources has come from an unlikely ally. When Smith first called Roux two years ago, he also wanted to talk business. Around that time, NFL Players Inc., the for-profit arm of the NFLPA, had been discussing ways to grow by offering its core set of group licensing services (including sales, business development, account management and legal financial services) to other sports properties. Smith and his team observed how the USWNT fought to bring its group licensing rights back in house during CBA negotiations and wanted to help maximize those rights.

“In the sports world, I think the most important way to organize athletes is around group licensing rights,” Smith says. “Those things are not only valuable from a monetary standpoint, but they’re extremely valuable in organizing your members around a common issue.”

Roux and her players were down for a partnership with the NFLPA. And not only that, but the WNBPA–the WNBA players' association–was going to be involved, too. In November 2017, the three players unions launched REP Worldwide, a unique take on brand management and representation. The company is a subsidiary of NFL Players Inc., and as founding partners, the soccer and basketball players are equity shareholders.

“Learning from them has been a good experience in the way [we] think about things and the way we structure contracts, and protect players and individual rights,” Klingenberg says.

.@TheWNBPA, @USWNTPlayers and #NFL players walk into a bar. What happens next?

— NFLPA (@NFLPA) November 13, 2017

🔗: https://t.co/ykCbYosQPG

📸: https://t.co/tmm8wjEsKG pic.twitter.com/bJdceIjFde

We had a great week at #SBLII deepening our partnership with the @NFLPA and @TheWNBPA. We are excited to bring more opportunities to our members and to effect positive societal change together. ⚽️🏈🏀#REPWorldwide pic.twitter.com/AlTKrkqztx

— USWNT Players (@USWNTPlayers) February 7, 2018

Steve Scebelo, the president of REP Worldwide, says the USWNT will have at least 25 signed licensing agreements by the time the World Cup begins. He’s conservatively estimated that if the Americans win a fourth title this summer, the 23 players on the roster will have at least a million dollars in royalty revenue to split equally. The hope, Scebelo says, is for retail partners to sell merchandise through the holidays, into the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and beyond.

“Growing up, you knew what Disney movie was coming out next because the McDonald’s Happy Meal toy was a character,” Roux says. “Licensing and merchandise are walking billboards. How else are people supposed to know who our players are?”

REP Worldwide gives athletes something to celebrate #sportsbiz @PierreGarcon @meghankling @ChristenPress @Chiney321 @monnie22 @beckysauerbrunn pic.twitter.com/8umm75sHcF

— NFLPA (@NFLPA) November 27, 2017

REP Worldwide was officially launched at a November 2017 friendly between the U.S. and Canada. WNBA and NFL players attended the match at Avaya Stadium in San Jose and afterward they met their new business partners. LA Sparks forward and players association VP Chiney Ogwumike remembers chatting with Carli Lloyd and both airing grievances about everything from wanting the same respect NBA players get to better benefits not just for the national team, but the NWSL, too.

While forming REP Worldwide was important for what it symbolized, it was also meaningful for what it’s enabled: getting athletes from different sports in a room together. It’s also facilitated a bond between Roux and WNBPA executive director, Terri Jackson. WNBA players opted out of their CBA last November, a deal that was originally supposed to run through 2021. Players have been vocal about low pay, inadequate working conditions and wanting small changes that will greatly impact players. In a Players’ Tribune letter, WNBPA president Nneka Ogwumike said opting out isn’t only about salaries, “this is about a six-foot-nine superstar taking a red-eye cross-country and having to sit in an economy seat instead of an exit row.”

Roux shared her CBA document with Jackson as she and the WNBA players prepare for negotiations with the league, and specifically walked her through maternity and adoption clauses. Says Jackson: “We are more of a resource to each other than we could have ever imagined.”

The USWNT has made a lifelong habit of serving their peers. Foudy, a two-time World Cup champion and Olympic gold medalist, has been a mentor to the U.S. women’s hockey team since the 90s and remains a trusted advisor. Especially now, with 200 players recently deciding to boycott playing professionally this season in an effort to create a more sustainable league with better pay.

“My big message to them was you have to constantly make the team aware that what you’re doing is for the next group and you have to stick together,” Foudy says. “I just share insight. They’re still a work in progress, still fighting, still frustrated. Even though the CBA is better, you’re still not changing the mind of your federation, which doesn’t wake up going, ‘How can we build this market out?’”

As the Women's World Cup begins later this week, eyes are on the U.S. women. They’re a unique property in sports that some, like Coyne Schofield, want to emulate; and others, like Smith (who is slated to be in France during the competition), want to help. Most importantly, everybody understands they’re in this together.

“I really feel like it is an amazing time to be a woman, and I think it’s an amazing time in women’s soccer,” says Press. “[Our fight] helps everyone and you have to have the people who can fight, fight. What I hope, and what I believe has happened, is the beginning of a paradigm shift.”