Diego Maradona Film Review: A Story of Humanity, Deity, Icarus & Football

"With Diego, I would go to the end of the world. But with Maradona,

I wouldn't take a step."

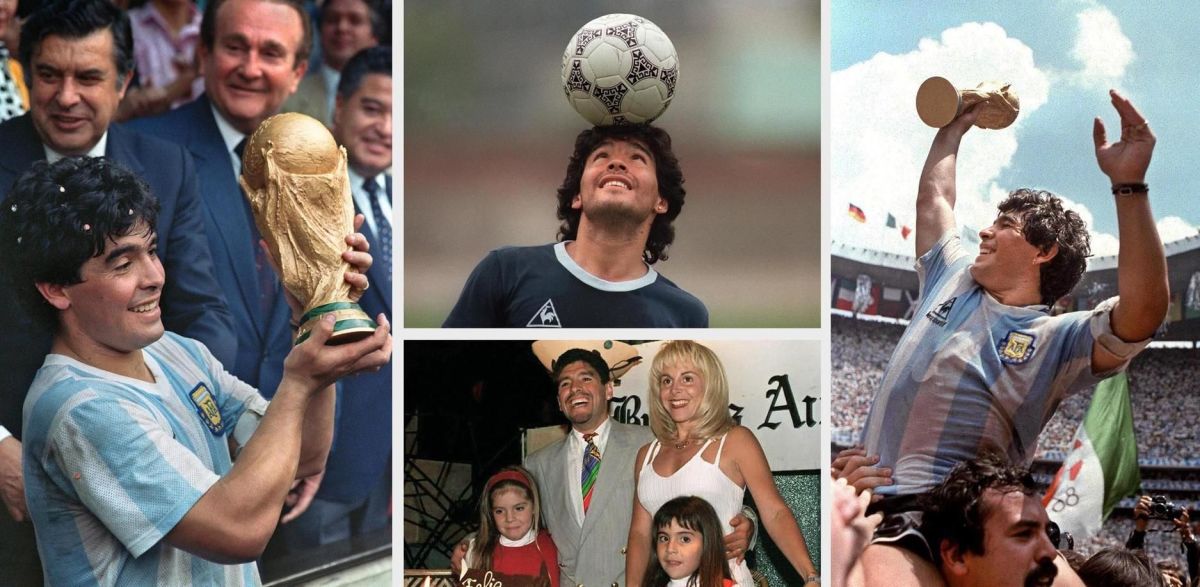

Diego. Maradona. There are no two names in world football that come with as much joy, as much anger, as much wonder and as much baggage. In fact, few names in world history could match them.

And, as is made abundantly clear in Asif Kapadia's latest eponymous cinematic masterpiece, they were two very separate entities. If the use of both names in the title of the film doesn't tell you that - following on from the one-name explorations of Amy Winehouse (Oscar-winning) and Ayrton Senna - then the above quote from Diego's long-time personal trainer, Fernando Signorini, will. In no uncertain terms.

And, while I cannot stress to you enough how important it is to see this film in its entirety, and preferably at the cinema - there are few times in your life you will ever get to see and feel football in such a visceral way - that 19-word message gets right to the film's core. It speaks to the unrivalled beauty of the footballer, both with a ball at his feet and a camera in his face - I'd put 1984 Maradona up against any of the great Hollywood heartthrobs - and the ugliness that simmered within him, barely beneath the surface.

His story, like all great stories, is one that is bursting with both one-of-a-kind originality and timeless depictions of suffering. It tackles with the deity of Diego and the flawed humanity of Maradona, and the blurred lines between both. It's 'Goodfellas', it's 'Gangs of New York', it's 'Goal'. And it's magnificent.

But it is also a documentary, and this is utterly fundamental to its greatness. Because, as 'Goal' showed, the intensity of football is, perhaps more than any other sport, extremely hard to replicate. Combine that phenomenon with the fact that Maradona, with his perfectly coiled curls, fluctuating physique, diminutive stature and mesmeric control of the ball, is inimitable in every way, and you have a recipe for fictionalised disaster.

Which makes you consider the unparalleled wonder of sport. Because, as two recent biopics of Freddie Mercury and Elton John have shown, it is remarkably easy to reconstitute that kind of talent, whether you sing or not.

With CGI and a bit of bravado, you can recreate the power of Live Aid. You could never similarly reproduce the scenes in and around the Stadio San Paolo in 1987, nor the otherworldly exploits of Maradona in that fateful quarter-final against England at the '86 World Cup.

It begins with a frenetic car journey to the San Paolo in July 1984, the day of Diego's unveiling at Napoli, interspersed with a bone-crunching, midriff-kicking lowlights reel from his unsavoury time at Barcelona in the years before.

And it is these seven years in Naples, traversing two World Cups, which the film focusses on, because, well, for both on-field marvels and off-field antics, have there ever been a greater seven years in football history?

The Argentine arrived in Italy with Serie A at its competitive pomp - for context, a Franco Baresi-led Milan side had only just returned to the top division following relegation - and, instead of joining champions Juventus, or high-flyers Roma, Inter or Fiorentina, he opted for the Partenopei, who had escaped relegation by one solitary point in 1983/84.

Within three seasons, the club had not only secured the first Scudetto of their existence, they'd won just the third double in Italian football's illustrious history. Yes, that was the season after he'd single-handedly - no seriously, try name another player - won the World Cup in Mexico.

Which is where the GOATness of it all comes in. It is not a novel statement to call Diego the Greatest of All-Time - we did just the other week on this very site - but it's not exactly fashionable these days. And yet, I challenge even the most ardent Lionel Messi maniacs or Cristiano Ronaldistas to not watch Maradona do what he does and question their tightly-held, keyboard-bound beliefs.

Because, in the same calendar year, he achieves arguably the two greatest feats of club and international football, for two of the most downtrodden sides/cities/countries of that decade, and he did it with a combination of individual brilliance, magnetic charisma and unyielding willpower that have not been seen since.

Sure, you lot might have the stats, but Maradona has the look. That mythic, unwavering, inspiring look that sends tingles down your spine, that makes you believe you can win the game's most coveted prize, even if you're playing in the Spanish second division, as one '86 Albiceleste squad member, Marcelo Trobbiani, was.

Which is what makes what Maradona eventually does with his talent even more depressing. The drug-induced demise is fraught, and well-documented, but never with the archival footage that is offered here.

Or is it the talent that makes him do it? This is one of the hypotheses that the film seems to present. Because, even in the wild celebrations of these spectacular triumphs, you can see the great cost; it is written, unsparingly, in the cowering brow of Diego when he is crushed by an overexcited press core at a hometown airport following the World Cup triumph, or when his car is encircled in the streets of Naples because it's a Tuesday and there's nothing better to do.

At the same time as seeing this, we are regaled with stories of doctors stealing vials of his blood during routine tests.

Claustrophobia is a well-known side effect of fame, but rarely is it more effectively depicted than in these limb-melding melees. One of the defining shots of the film shows Maradona at the Napoli Christmas party in the aftermath of Italia '90, just as the local press are in the midst of pulling the rug from under his time in the country, planting the seeds for his Mafia-entangled downfall.

Nothing happens, no fireworks, the camera merely lingers - while penetrating deeper and deeper through zoom - on his expressionless, as he contemplates his upcoming dethroning. Or maybe he was just embroiled in a particular brutal comedown.

Either way, it's the most haunting thing I've seen on screen in a long time.

'Diego' was the sweet kid who grew up in the slums of Villa Fiorito and lived to play football. 'Maradona' was the persona he created in order to deal with the pressure of the life the game gave him.

Yet, despite fighting for the downtrodden throughout his footballing career, and uplifting them in a way few ever could, it's clear he could never escape that feeling himself. In both adulation and disgust, the crowds ensnared him, baying for either a touch of their hero, or his blood.