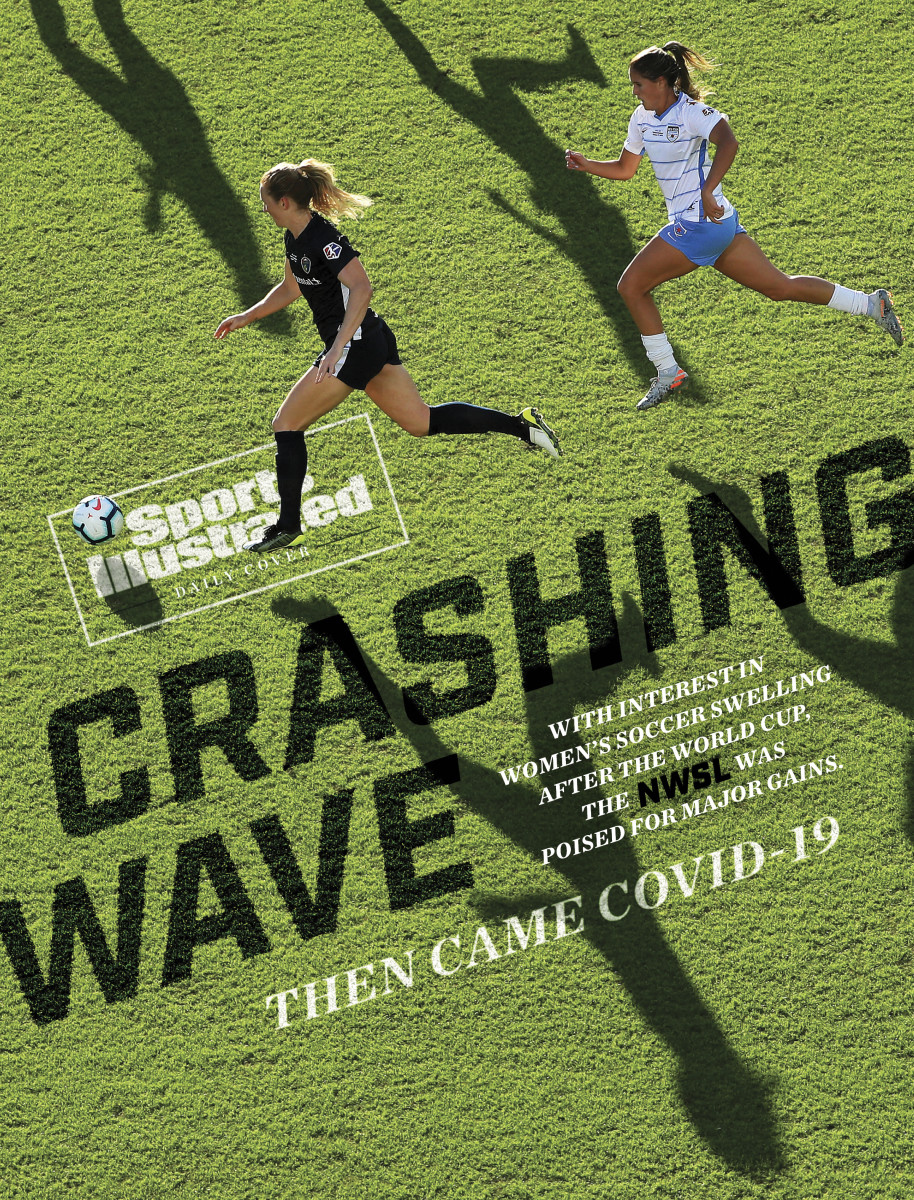

Will the Pandemic Crash the National Women's Soccer League?

Emily Menges likes to move. Before games, the Portland Thorns FC defender generally strolls around town, stopping at a farmers’ market (“So Portland,” she says. “I know.”) before heading to Providence Park to warm up. So on Saturday, April 18, which should have been the Thorns’ National Women’s Soccer League season opener—broadcast on CBS All-Access—she awoke with a pit in her stomach. The game had long been canceled. So had the farmers’ market.

Menges just hopes this break, caused by the pandemic, doesn’t become permanent.

“I do worry,” she says. “Every player knows how precarious this league is. It is scary to think about.”

She is right to be concerned. Since its 2013 launch, the NWSL has faced a central paradox: Despite featuring beloved World Cup heroes, the league has failed to attract widespread notice. This season, though, it finally seemed poised for a breakthrough: Stars like Megan Rapinoe, Alex Morgan, Carli Lloyd and Rose Lavelle have reached new heights of celebrity—and the media was catching up. On March 11, the NWSL announced a landmark deal with CBS that, for the first time, would air games on network TV. Just a few hours later, though, Rudy Gobert tested positive for COVID-19 and the NBA shut down. The NWSL followed, wiping away not only Menges’s season opener in Portland, but that day’s CBS headliner, between Lavelle’s Washington Spirit and Rapinoe’s OL Reign.

While all U.S. professional sports leagues face challenges—the pandemic has already shuttered the XFL—few run on quite the same shoestring as the NWSL. The league does not divulge revenue, but its minimum salary this year is $20,000. In the WNBA, it’s $57,000. In the NFL, it’s $510,000. For players, the travel is commercial and the perks nonexistent: Some teams work out not in state-of-the-art complexes, but local gyms.

U.S. Soccer, the national governing body, helps keep the NWSL afloat by paying club salary and benefits for the 23 players on the national team—$1.4 million last year—and providing other management services, which included $843,000 of administrative expenses last year, according to an internal audit. Some people in women's soccer have expressed concern over the status of that arrangement. In April, amid laying off and furloughing dozens of employees, U.S. Soccer applied and was approved for government relief via a Payroll Protection Program loan. This week, however, U.S. Soccer decided to return the loan. Asked whether its subsidy of the league could be imperiled, a spokesman for U.S. Soccer said, “Nothing has changed in terms of our financial support.”

[Editor's note: After this story was published, U.S. Soccer updated the status of the PPP loan.]

Amanda Duffy, the former NWSL president who is now executive vice president of the Orlando Pride, points out that the league is well-suited to survive, since it’s used to budgeting as if it can afford no extravagance.

“The NWSL was going to be entering its eighth season of operating but is still very much in its infancy,” she says. “We haven’t moved out of that stage of making every single decision related to keeping the league in business.”

Still, the league had moved forward with plans to grow its profile, in part by attracting more international stars with lucrative opportunities. The introduction of an allocation money system–akin to the one implemented in MLS, where an extra allotment of money can be used to spend beyond the salary cap on players whose salaries can exceed the league maximum–promised to lure some big names. One of them, France's dynamic Kadidiatou Diani, was potentially headed from Paris Saint-Germain to Portland. But the pandemic and the logistical and medical concerns it has carried changed everything. Diani, 25, wound up re-signing with PSG through 2023 earlier this month.

"Just didn't make sense given all the variables of these times. Respect the decision and will see what happens in the future...." Thorns FC owner Merritt Paulson, who also cited Diani's personal and family aspects, wrote on Twitter.

The timing of all of this could scarcely be worse: Many Americans seem to care deeply about women’s soccer only when the U.S. women’s national team is playing in the World Cup or Olympics. Those are offset such that every four years, there is a World Cup one summer and an Olympics the next. Those 12 intervening months represent the best chance for professional women’s soccer to break through the public consciousness.

People within the NWSL expected this to be the best stretch yet: Last July, the U.S. national team had defended its title at the World Cup in France with an average live audience of 82.18 million people for the final. NBC said it expected 200 million Americans to watch the Olympics. And last year’s NWSL attendance was up 21.8% per game over 2018, to an average of 7,337 fans. Seven of the nine teams drew franchise-record crowds.

However, they now face a foreseeable future without fans. Epidemiologists agree that it will likely be unsafe to gather large crowds until a coronavirus vaccine arrives—potentially more than a year from now. In the meantime, people familiar with the NWSL’s plans say clubs are split on whether the league can afford to stage contests in empty stadiums. Some teams, such as the Thorns and Utah Royals FC, which draw well, rely on gate revenue; others, such as the Houston Dash, were not expecting much in the way of ticket sales anyway. They might be able to forge an agreement if a sponsor is willing to eat some of the cost.

The alternative might be worse: a season without games at all. And here is another place the NWSL faces a disadvantage. Even if the 2020 season is canceled entirely, Yankees fans are not going to forget that they are Yankees fans. Sky Blue FC fans might need some reminding.

“You’re going to lose the margins,” says Julie Foudy, the two-time World Cup winner and two-time Olympic gold medalist who now calls soccer for ESPN. “You’ve got to continue to keep [fans] emotionally engaged, to give them a reason they’re going to spend their limited resources [on the NWSL] when the games do open up.”

Until then, the NWSL is trying to navigate a path forward. When President Donald Trump held a conference call with league commissioners in April, he notably left off NWSL commissioner Lisa Baird, but people familiar with the league’s plans say that the NWSL hopes to be among the first leagues to return to action. (Baird, through a representative, declined to be interviewed for this story.) Players have been asked by teams to return to their areas by May 16—a date that, as of press time, had not been changed—and have begun planning socially distanced workouts at their facilities: one player at a time, each with her own ball and cones, wiping down everything she touches afterward. Eventually they hope to progress to small-group training with coaches directing from the stands.

“I think the league is going to do every single thing they possibly can do to stay open and have some kind of a season,” says Menges. And, she points out, the NWSL is not alone in its dashed plans. The coronavirus has also pushed back the Olympics. Maybe women’s soccer can sustain some of its momentum after all.