'At the End of Mourning, You’re Supposed to Disengage'

In the heart of Buenos Aires, the Obelisk—a white concrete cousin of the Washington Monument—is a place to celebrate greatness. The greatness of one of the world’s key port cities. The greatness of any number of soccer outfits, whether it be an Argentine club or the national team, whose fans flock here to toast triumphs in major competitions. Or, say, the greatness of an individual. On March 10, three and a half months after Argentina’s most beloved public figure died of congestive heart failure, the Obelisk is where thousands of angry acolytes joined the ex-wife and two daughters of Diego Maradona to celebrate the soccer legend—and to demand justice following reports of negligent medical care surrounding his death at age 60.

They sang. They blew horns. They waved sky-blue-and-white flags.

They cried. They chanted. They fired off flare guns.

“It was a demonstration that he was alive, that justice needed to be done,” says José María De Andrea, who was part of the throng that southern summer day at the Obelisk. De Andrea, 47 and a father of four, is a member of the Church of Maradona, a group of spiritually hardcore devotees that was founded in 1998. “As a soccer player, he’s a god,” De Andrea says. “I have seen extraordinary things over the years. I have shed tears.”

De Andrea can speak in endless detail about the church’s lodestar, including his first memories of the man, watching at his grandmother’s house in 1981 as Maradona and Boca Juniors won the Argentine league. Five years later, when Maradona led his country to the World Cup title in Mexico, De Andrea was 12. And he was hooked. “I celebrated in a Fiat 600, a very small car. There were like 12 people inside of it,” he says. “The magic I saw in that World Cup! We touched the sky with our hands.”

De Andrea demonstrated last November, too, joining thousands of mourners at the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s version of the White House, where Maradona’s casket lay in state. That scene turned violent when authorities threatened to remove Maradona’s casket before the entirety of the gathered crowd had been able to see and mourn him. Angry citizens confronted police, threw barricades and scaled walls. Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets into the masses. “These people hugged and cried. We were there solely for him,” De Andrea says. “But here in Argentina, things get out of hand.”

If there’s any comparison to be found to the ongoing fervor over Maradona’s death, it’s in the public outpourings, recriminations and eventual court cases following Michael Jackson’s death in 2009. Weeping masses. National and global mourning. The greatest hits running on constant loop. And the parallel makes sense. Maradona’s mythology in his home country always resonated far beyond the sporting sphere. He was Argentina’s most prominent celebrity of any kind.

Outrage, naturally, ensued April 30, when a special board that had been appointed to investigate Maradona’s death concluded that his own medical team acted in an “inappropriate, deficient and reckless manner” following his brain surgery for a subdural hematoma last November. Seven members of that team, including neurosurgeon Leopoldo Luque and psychiatrist Agustina Cosachov, were indicted on charges of “simple homicide with eventual intent.” (All seven have denied any wrongdoing.) Court hearings began in June and are expected to continue into the fall, with a judge deciding at some indeterminate point whether the case will go to trial.

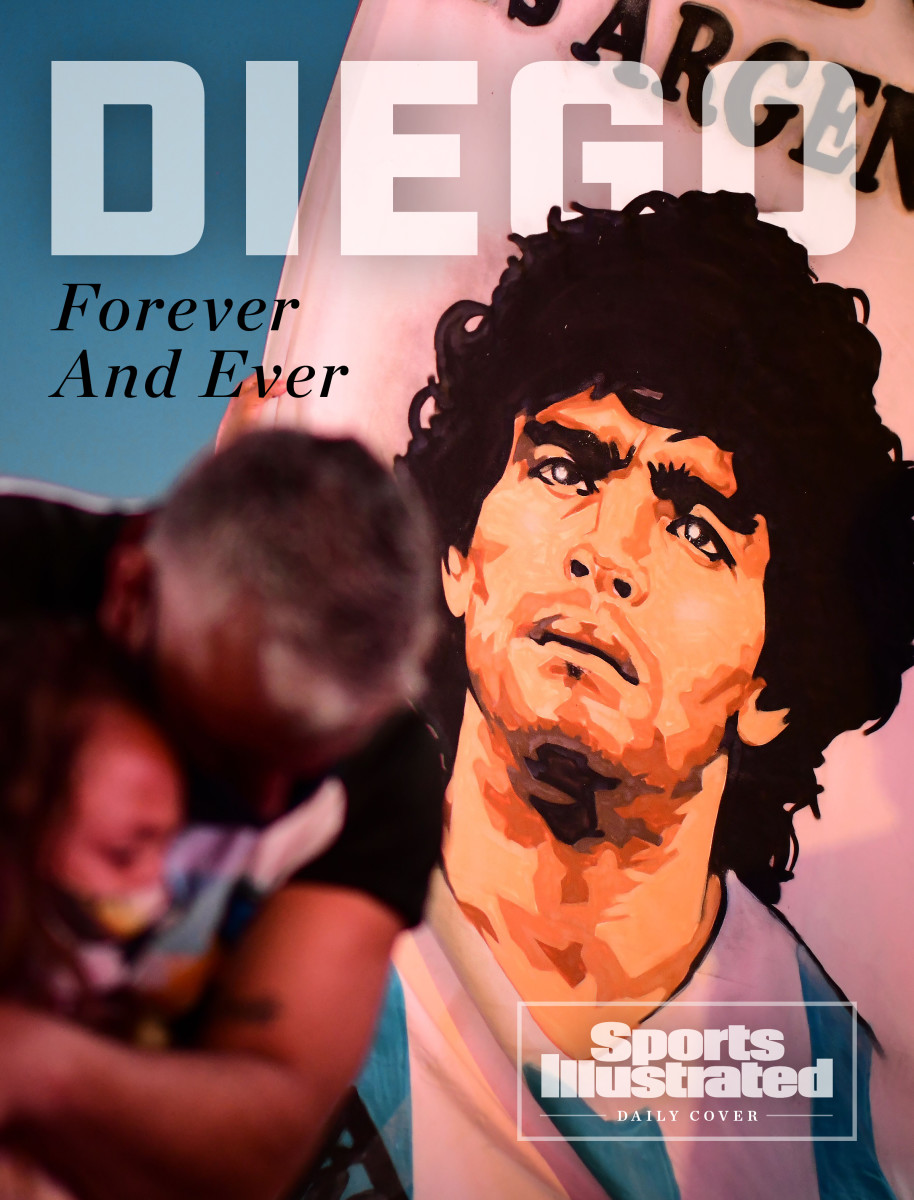

What’s indisputable, though, is that the mix of worship and outrage—a soccer player’s posthumous grip on Argentine society—remains just as strong nine months after his death. Maradona-themed graffiti and artwork are everywhere in Buenos Aires. Billboards of the teenaged, mop-haired player with his parents, Don Diego and Doña Tota, are plastered across the city, reminders of a time with infinite possibilities. The words “Diego Eterno” (Diego Forever) appear on signs and on flags.

“I imagine that if they had scheduled a month-long funeral,” says De Andrea, “it would have been full the whole month.”

So: Why has the reaction been this … extreme? And what can that reaction tell us about the man, the country and his place in it? For years I have been fascinated by a particularly Argentine phenomenon: the elevation of Maradona to a godlike status on par with Eva Perón, who also grew up in poverty and became a global icon, as the first lady of Argentina. Today, Maradona’s stature here is far above any other soccer player’s, including Lionel Messi or anyone on the country’s other World Cup–winning team, in 1978. And, for that matter, far above the cultural position of his longtime rival, Pelé, in neighboring Brazil. Argentina is my adopted second country; in ’95 I lived there for three months, researching my college thesis (on the nation’s politics and soccer), and I have since visited more than a dozen times, including for Maradona’s testimonial match, in 2001.

I know my stuff. But I am not Argentine. And so I sought to learn from those who might know better than me.

Andrés Cantor can’t read the news stories anymore. Last January the legendary soccer broadcaster, known largely for his trademark Gooooal! calls, stopped consuming the coverage of Maradona’s final agonizing days. His decision came soon after the Argentine news site Infobae first published an exposé revealing callous and seemingly damning WhatsApp messages between Maradona’s caregivers, suggesting that they had been negligent in his medical supervision and had left him alone in his room for the last 12 hours before his death.

Those messages, says Cantor, are “so sad to hear. So I made myself a promise just to read the headlines—but nothing more than that. It’s like salt in the wound every time.”

Born in Argentina and now living in Miami, Cantor can’t escape the notion that the sport he grew up worshipping died along with Maradona, who dominated a World Cup (in 1986) like no other player ever has; who won two Italian league titles with Napoli; and who possessed a swashbuckling verve and genius with the ball that were uniquely his own. Yes, there were drug and alcohol addictions, children born out of wedlock in multiple countries, conflicts and an air-gun incident with reporters. But Maradona remains a deified figure among his supporters.

Cantor can still remember clearly the first times he watched the teenaged Maradona play the sport. “That was when the love affair started, and I wasn’t the only one,” Cantor says. “He played football like nobody else. I enjoy Lionel Messi. I enjoy Kylian Mbappé. I enjoy Cristiano Ronaldo. All the great players of today. But I haven’t seen one close to Maradona. So I’d say that, symbolically, football died with him.”

For Cantor, it’s all deeply personal. In 1979, while reporting a story for the Argentine magazine El Gráfico, Cantor sat in the back of a Chevy Camaro, laughing, as the 18-year-old Maradona screeched through the streets of Los Angeles on a test drive. In ’83, Cantor took the budding hero to a hot New York City club, only to flee from their front-row table when they experienced firsthand that the crowd threw bottles at unfavored bands. And in ’87, after Maradona won his first Italian league title, Cantor witnessed the fan fervor in full: He was in a line of 15 cars on the way to a celebratory party when the sight of Maradona speaking to a tollbooth operator caused havoc among the vehicles moving in both directions. The two men continued to connect over the years, usually at World Cups, always meeting with a hug.

Like so many people who knew Maradona personally, Cantor disapproved of the full-time hangers-on who surrounded the superstar and indulged his worst vices over the years. But Cantor never suspected that this group would ever include Maradona’s doctors, lawyers and caregivers.

“I still don’t believe he’s gone,” Cantor says. “He’s the person who gave me the most joy in the world of soccer. For the life of me, I cannot understand how the biggest idol in Argentina was left to die this way.”

Argentines detest the mediocre and fear to be thought mediocre. It was one of Eva Perón’s words of abuse. For her the Argentine aristocracy was always mediocre. And she was right. In a few years she shattered the myth of Argentina as an aristocratic colonial land. And no other myth … has been found to take its place.

—V. S. Naipaul, in The Return of Eva Perón, 1980

Naipaul, a Nobel Prize–winning author, was a few years too early. Maradona would create his myth at the 1986 World Cup. But other soccer players have delivered international glory to Argentina, have risen to Maradona’s heights in the club game. So why do Argentines view him as if he exists on a wholly different plane?

You can find reasonable soccer enthusiasts around the world who will argue that Messi is the greatest men’s player of all time, even better than Maradona or Pelé. Usually that argument rests on the notion that in the modern game the annual UEFA Champions League, which Messi has dominated individually, is a better measure of greatness (with a larger sample size, all the best players and a higher standard of play) than the quadrennial FIFA World Cup. But the people making that argument are rarely Argentine. Messi’s compatriots have at times been merciless about his not winning a World Cup—or, until this summer, any major senior title—with his national team. They have even characterized Messi, who moved to Barcelona at age 13, as being more Spanish than Argentine.

But if Argentines use World Cup victories as the standard for greatness, then why is Maradona’s status not shared by Mario Kempes, who scored six goals (one more than Maradona netted in Mexico) as La Albiceleste won the 1978 World Cup on home soil? Kempes is respected and admired, of course; he has a stadium named after him in his hometown of Córdoba. But he holds no mythology in Argentina. And so I asked Alejandro Gardella, an old friend of mine who has lived in Argentina, the U.S., Brazil and Great Britain, and who has always been interested in seeking out Argentine and non-Argentine perspectives. (He has even spent time reporting in the Falkland Islands, which few Argentines have visited since the end of their country’s 10-week war with Great Britain, in ’82.)

Gardella, a 50-year-old HR exec, lives with his three children in Tigre, the Buenos Aires suburb where Maradona spent his final days, and my friend puts Argentina’s soccer conquests in the context of what the nation was experiencing at the time. The 1978 World Cup, he argues, “was mixed with the dictatorship in the Argentine psyche. We won, but the junta”—the right-wing military group that in ’76 overthrew president Isabel Perón—“was involved [in organizing the tournament]. We had ‘the Disappeared’ ”—the state-led killing of thousands of citizens—“and people were being tortured near the stadium. It was like a dirty World Cup. Then we lost the [Falklands] war in ’82. But in ’83 democracy came back, and free elections were won by a moderate guy, [president Raúl] Alfonsín. When we won the ’86 World Cup, that was the real thing. And at the helm of ’86 was Diego.”

By winning under those circumstances, Gardella says, Maradona evoked a better time, a century earlier, when Argentina had one of the world’s most prosperous economies. He represented an “avenger hero for the country.” Never was that more the case than in the quarterfinal against England, four years after the Falklands fiasco. In that game, Maradona scored two of the most famous goals of all time, just four minutes apart: the so-called Hand of God goal, in which he got away with punching the ball into the net; and the greatest goal in World Cup history, a 70-yard slalom run through six England players, in which Maradona touched the ball with only his majestic left foot.

“I would dare say that [Maradona’s mythology] was more about that game with England than winning the World Cup itself,” Gardella says. “It was a revenge. We had lost the [Falklands] war, and that was a deeply rooted thing in the pride of the nation. The first goal”—the Hand of God—“was part of the local psyche. Cleverness with an edge is like an asset here. It was like, We screwed you in a way that you’re going to regret for years and years. By winning, we recovered something that had been lost, and we did it during our political renewal.” (My old friend laughs remembering how he eventually moved to London for a few years and there discovered that the sense of enmity over the Falklands wasn’t the same as back home. “I thought I would be looked at badly in London for being an Argentine, and actually they didn’t give a f--- at all,” he says. “I told myself: I need to reformat my head about these guys.”)

The myth of Maradona was just as much about what he represented to Argentines as it was about what he accomplished on the field. He became the national apotheosis of the so-called pibe archetype, the kid from the streets with a dusty face and a thatch of black hair whose cunning and instincts give him an edge over those born into privilege. Maradona grew up in a Buenos Aires shantytown, and though he eventually became fabulously wealthy, he never lost the qualities of improvisation and misdirection that served him so well against bigger and stronger opponents.

There’s another paradigm that applies to Maradona and that is celebrated in Argentina, notes Carlos Forment, a professor at the New School for Social Research (and my college thesis adviser) who lives for part of the year in Buenos Aires. “The picaresque hero is a classic part of Spanish literature, and Maradona has some of that,” says Forment, the author of Democracy in Latin America. “It harks back to his plebeian origins. This is really central for Argentine political culture: [It’s valued] to be from the bottom and rise to the top—and once you’re at the top to scorn the elite.”

Evita had that. Maradona had that. It’s a characteristic, moreover, that tends to separate Argentina from Brazil.

Why do Argentines revere Maradona in a way that Brazilians don’t hold Pelé? These two are, with little global debate, the two premier men’s soccer players of the 20th century. Pelé, now 80, won three World Cups, two more than Maradona, and performed more consistently at the club level for a longer period of time. ... Maradona, unlike Pelé, played in the European club game, winning Napoli’s first league trophies at a time when Italy’s Serie A was at the height of its powers. … As breathtaking as Pelé was during his career, Maradona’s ceiling from 1986 to ’90 was even higher. ...

One can argue forever over which player was better, but there’s no denying that Maradona’s place in Argentina’s cultural firmament is on a higher level than Pelé’s in Brazil. Pelé has plenty of admirers; he’s a beloved figure around the world. But you don’t need to spend much time around Brazilian soccer to find contrarians who contend that the dribbling maestro Garrincha was a better player, or that Pelé has been too corporate in his pursuit of endorsement riches. It’s a measure of Maradona’s status within Argentina that he’s idolized just as much by fans of River Plate—the archrival of his former club, Boca Juniors—as he is by everyone else in the soccer sphere. Yet Pelé, who played near São Paulo, for Santos, has never totally won over fans in Rio de Janeiro, where public backlash recently led government officials to scrap a proposal to rename the Maracanã stadium after him.

Of course, there’s context to consider. Maradona, for starters, was 20 years younger than Pelé, which means that millions more people in today’s Argentina lived through the visceral experience of watching their star’s finest moments in real time. There are also historical and cultural differences between Argentina and Brazil, Forment points out, that create better conditions in Argentina for the deification of a larger-than-life figure.

“Brazil is a very hierarchical and structured society, and that produces very stable institutions—even when they had a dictatorship, it was a stable dictatorship,” says Forment. But “in Argentina, because it’s not institutionally stable, they don’t function well, and everything’s kind of chaotic. That opens the space for the rise of a heroic figure, because that person becomes more powerful than the institutions.

“The dark side of this is that there’s no authority. That’s why institutions crumble, why people don’t pay taxes, why traffic is [terrible] in Argentina. Maradona, in many ways, symbolizes all of this. There’s a kind of improvisational quality, very creative, in Argentina. You see this in art, in music. … But when you translate that into running a society, you need to have a little order as well. And that’s what’s lacking here.” In other words, the instability in Forment’s and Maradona’s Argentina helped create not just the myth of the superstar pibe soccer player, but also the chaos in the aftermath of his death.

The word order appears on the national flag of Brazil, but not on Argentina’s. That Maradona is bigger in his country than Pelé is in his should come as no surprise.

Last November, when The New York Times headlined its Maradona obituary THE MOST HUMAN OF IMMORTALS, “human” was meant to suggest—not inaccurately—that the man was flawed in a deep and abiding way. But the word human has other connotations, too. Maradona was transcendent because he was not some untouchable figure among the gods.

“Maradona is, for two or three generations, part of our family,” says the Argentine sports journalist Verónica Brunati. “He’s the person who gave us the most important happiness in football. And you know what football means for Argentines—it’s our passion, our identity. When a woman is pregnant, the first thing we think of is the name. And if it’s a boy, the first name we think of is Diego.”

Brunati did not, in the end, name her own son after Maradona, but she did have a closer perspective of the man than most. In 2007, she helped arrange the first joint newspaper interview with Maradona and Messi, and she remembers being touched when Maradona took Messi’s arms and prayed to him like a son, saying, “You are going to be better than me.” Later, while Maradona was managing the Argentine national team, he earned a laugh from Brunati, who was pregnant, by placing his hand on her stomach and “blessing” her child. (She recalls her husband saying, “My son is going to be a football player because Maradona did this!”) Maradona eventually met that son, Agustín, at an art exhibition that Brunati organized. The boy was nearly 2, and Maradona made a ball out of crumpled-up paper, playing with him in the museum. “He was so friendly, so lovely,” Brunati says. “I couldn’t believe I was watching my son play with Maradona.”

In July 2014, on the night before Argentina won its World Cup semifinal, Brunati’s husband, Jorge “El Topo” López, died in a traffic accident in São Paulo when his taxi was struck by a car fleeing police in a high-speed chase. During the days and weeks after the tragedy, as calls grew for accountability from Brazilian police, some of soccer’s most prominent figures—including Messi, Pep Guardiola and Diego Simeone—took part in a campaign seeking justice. But Brunati remembers above all the man who reached out to her with a personal message: “When my husband died, Maradona was the first person in the world who sent me the message ‘Justice for Topo,’ ” she says. “He was the first.”

Earlier this summer, during the Copa América soccer tournament, the Argentine beer company Quilmes ran a television ad that could easily have been scripted by the writer Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine master of magical realism. In the spot, Argentina and Brazil are tied in the dying moments of an imagined final at the Maracaña when an unseen mystical force, symbolized by tango music, redirects a Brazilian free kick off of Argentina’s crossbar and sends the ball on a long, mazy path back toward the opposite end of the field. Eventually the ball reaches and then teeters on Brazil’s goal line before finally rolling in for the deciding score. As overjoyed Argentines at home celebrate a miraculous triumph over their archrivals, the ad delivers a final message: It’s the first Cup with God in the sky. If he did what he did on the field, imagine it from the heavens. (No imagining was necessary: On July 10, Argentina beat Brazil 1–0 in the Copa América final at the Maracanã, marking the country’s first major title since 1993.)

Nine months have passed since Maradona’s death, and in these parts it all still feels inescapable. The first thing Carlos Forment sees when he leaves his home in Buenos Aires every morning is a billboard. The same billboard is all over the city, capturing a teenage Maradona and his parents, frozen in time, an epic life’s journey still to come. The sign reads: AMOR ETERNO. Eternal love.

“One morning we wake up, I go outside, and it’s there,” Forment says.

Argentina, it is widely known, has more psychologists per capita than any other nation. Perhaps it’s not surprising that those who live there view the ongoing legal battles surrounding and the continued public bereavement over Maradona’s death through a psychological lens.

“There was a long period of mourning,” Forment says. “Normally, when you go into mourning, what you’re doing psychologically is you mourn the loss, and gradually you’re able to remove the person from your life. But in Argentina the mourning [for Maradona] became melancholia—when the object has disappeared but you remain attached to it. Which is strange. It’s not supposed to happen that way. At the end of mourning, you’re supposed to disengage.

“Argentines remain attached to this object, Maradona. And he’s not there anymore.”

• The Problems With the NFL's Deshaun Watson Investigation

• How the Failed Super League Exacerbated the Fan-Owner Dynamic

• He's Old-School. He Doesn't Do Analytics. And He's Thriving in Today's MLB.