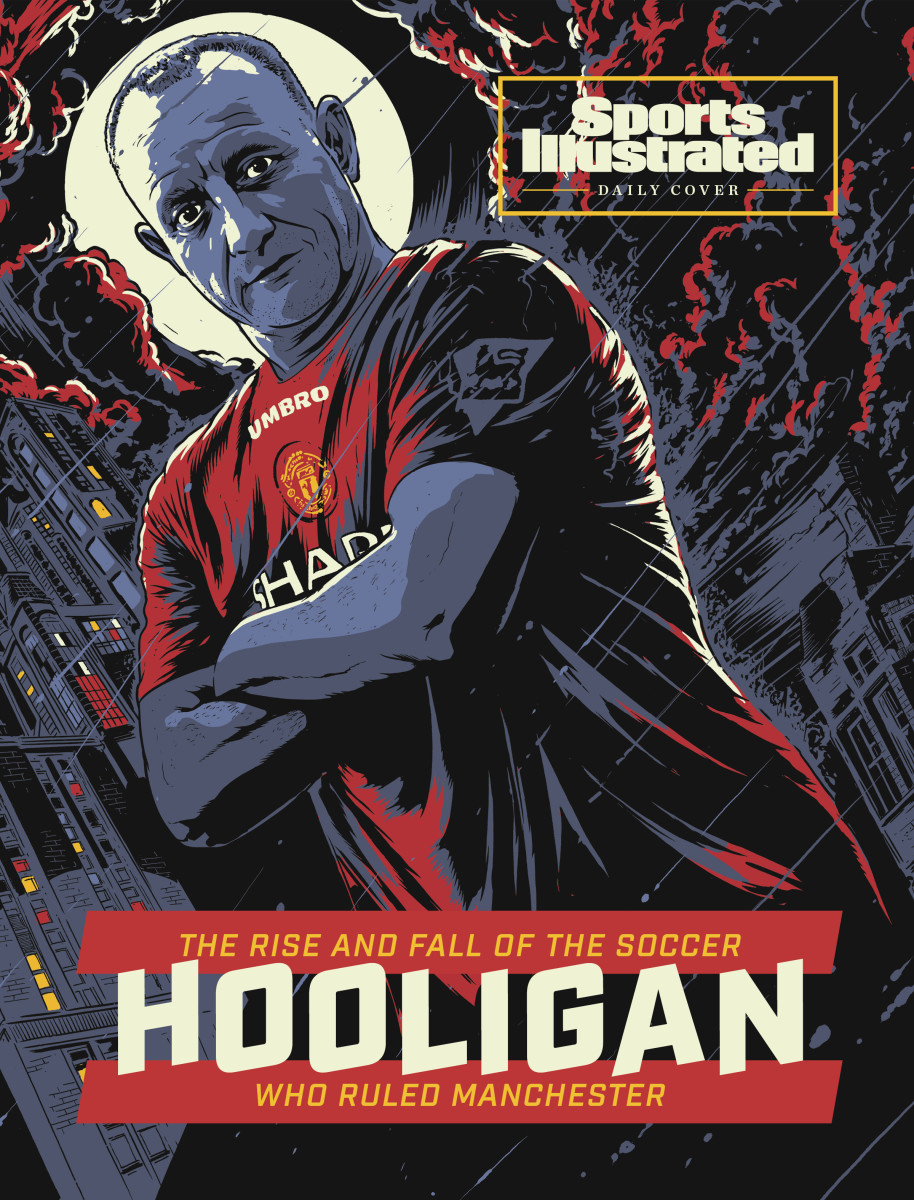

Guns, Drugs and Football Thugs: A Salford Murder Mystery

At 7:23 p.m. on July 26, 2015, Paul Massey parked his silver BMW 5 Series at a Bargain Booze on the outskirts of Manchester, England. Inside, he asked for his usual: a bottle of Bacardi and two liters of Coke. He tipped the cashier with the change and was gone within a minute.

Seventeen seconds behind him, a stranger followed.

It had already been a long day for a man used to long days. At 55, Massey was one of Europe’s most prominent gang leaders. He had spent half his adult life behind bars, for everything from a gasoline scam to a near-fatal stabbing. On the streets of Salford—a rough-and-tumble dock town of 100,000, nestled inside a meander of the River Irwell, just across the water from Manchester United’s Old Trafford stadium—he was known as Mr. Big.

Massey had first established himself as someone not to cross as a soccer hooligan in United’s Red Army, then as the head of his own crew. His Salford Lads weren’t a stringently hierarchical organization, like the Italian mafia, but a loose alliance of young criminals who in the 1990s supplanted the once-powerful Quality Street Gang. Locals knew Massey as someone who lived by a code. Sure, he had trafficked party drugs for years, but he drew the line at heroin. His men plastered stickers on lampposts threatening SELL SMACK, GET SMACKED. And yes, he was the man to see if you wanted a washing machine that had fallen off the back of a lorry, but he would also find money for the old lady whose flat had been broken into and cleaned out.

When rival gangs feuded, it was often Massey, never the cops, who brokered peace. He befriended gangland figures in prison and didn’t forget them on the outside: He would send Christmas cards with £50 included.

On that summer evening in 2015, Massey had just returned from Winkups Holiday Camp, on the Irish Sea in North Wales. The escape wasn’t as relaxing as he had hoped—one of his daughters, Kelly, called while he was away and remembers him being “a little distant, drained and stressed.” Massey carried two mobile phones that buzzed constantly with people asking for favors. Back in Salford, a gang war was unfolding, and a few associates made the drive out to Winkups to confer with Massey. Says Louise Lydiate, his partner of three decades and the mother of two of his five children: “The crown was heavy in Salford.”

The day he returned from holiday, Massey spent the afternoon with two gang associates, visited a bookie, bought the Bacardi and Cokes, drove the half mile home and pulled up to the wrought-iron gates outside his spacious red-brick colonial, set back from a busy road.

Nearby, an assailant, alerted by the stranger who’d tailed Massey, lay in wait.

At 7:27, as Massey stepped out of his car, a tall, athletic man—wearing a fake beard and dressed in combat gear, a witness later said, which made him look like a soldier in Call of Duty—hurried across the road, pulled out an Uzi and opened fire. It was the start of a scene for which Mr. Big had long been braced. “If it’s meant to happen, it’s meant to happen,” he told BBC documentarians back in the late 1990s. “I know the stakes.”

In the driveway, Massey’s left shin exploded. Bone fragments showered the gravel. He dropped the Bacardi, which shattered. A bullet struck three fingers in his right hand, tearing one digit clear off. Still, he was able to scramble behind some trash bins, take cover and dial 999 (the U.K. equivalent of 911), shouting, “I’ve been shot! Hurry up!”

“O.K., stay on the line for me,” the dispatcher replied.

“Hurry up,” Massey pleaded again, “he’s shot at—.” His phone cut out.

The gunman strode up to the bins and continued firing. Of the 18 bullets that flashed out of his muzzle, perhaps most crucial was the one that tore through Massey’s fifth rib on his left side, passed through his chest cavity, struck his heart and lungs, and lodged in his back.

As blood pooled in Massey’s chest and on the ground, the shooter ran across the street, raced through the graveyard of the Parish Church of St. Anne, headed toward a wooded area and hopped on a bicycle.

And then Mr. Big’s assassin pedaled away.

British tabloids couldn’t get enough of the Massey murder, which seemed plucked straight from Peaky Blinders or The Sopranos. Yet the case went unsolved, even after police identified more than 100 people of interest.

To understand how the cold-blooded, broad-daylight killing of such a renowned figure could remain shrouded in mystery, one must first understand the Salford code, which can be boiled down to two words. In the parlance of this world: Don’t grass.

Massey had considered grasses, or snitches, to be the lowest of the low. “If I got nicked and I’ve done something—I’ll go to prison,” Massey told the BBC. “I’ll do my jail. If I was to talk [to police], I’d just hang myself.”

In his world, nothing was more dishonorable than spilling to the cops, especially in Salford, the hardest part of Great Britain’s hardest, grayest region—a balkanized place of tough guys and gangsters, every one with a chip on his shoulder.

Manchester’s fortune had been cast during the Industrial Revolution of the late 1700s and early 1800s, when the once-sleepy Lancashire township’s climate and proximity to coal mines proved perfect for producing cotton and wool clothing. Soon Manchester was Cottonopolis, the global epicenter of textile manufacturing. The world’s first industrial city, though, suffered growing pains. As workers streamed in from the countryside, poverty reigned. Sanitation was abysmal. In a textile worker’s home on Silk Street or Chiffon Way, a dozen people might sleep in a single room. All the while, industry hurtled forward. Factories sought direct access to the Irish Sea, the Atlantic, the world. In 1894 the 36-mile Manchester Ship Canal let pass its first vessel. Even 40 miles inland, the port was the third-busiest in Great Britain.

Technically, the canal’s terminus was just west of Greater Manchester’s core, in a dock city filled with working-class ruffians and roustabouts. And largely, over the years, Salford has stayed that way. While the north of England has seen an influx of immigrants in recent decades, Massey’s hometown has remained, as Simon Harding, a criminology professor at the University of West London, puts it, “the last bastion of whiteness in the north of England.”

Salford stands in stark contrast to the Premier League sheen of Old Trafford, a short walk away. Street gangs have a celebrated history in England, dating back to the Dickensian poverty of the Industrial Revolution, and this is the type of place that gives birth to those gangs: poor and blighted, with terraced houses and scads of small pubs. This foundation of hardship, leavened with the coarse culture of textile factories and docks, and baked in with resentment from feeling looked down upon by richer Mancunians and more blue-blooded Londoners, was a recipe for Salford to become England’s most proudly pugnacious place. If there’s one thing a Salford lad enjoys more than a pint of Boddingtons, it’s a good scrap. “When they have a drink,” Massey said of his neighbors, “the lads from Salford, they just like a fight.”

So, perhaps Salford’s eventual place in the world of sport was inevitable. It just had that brawling nature, that contempt for authority. And it had Old Trafford, home of England’s most illustrious soccer club, a rare fountain of pride, right in its backyard.

In the 1970s and ’80s, while a young Massey was stealing crates of beer from Whitbread’s Brewery and getting sent off to reform school, hooliganism, a part of soccer since the sport’s inception, was spiraling the English game toward its dark nadir. Innocent bystanders, in the stands or on a train platform, would find themselves stuck between two factions of overcharged supporters—say, Manchester United’s Red Army and Liverpool’s Urchins, to single out some usual suspects—and get punched or clubbed. Or worse. Hungry-for-blood fanatics would sharpen the edges of two-pence coins or spark plugs and throw them into crowds. They would take over train cars and brawl with police. In the Midlands, a goalkeeper was injured by a block of flying wood. In London, a fan was killed in a postmatch riot. Doors at some stadiums were closed to visitors. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher convened a “war cabinet” to address it all. And in this violent epidemic, Manchester was a hot spot. After United was relegated to the second division, in ’74, its hooligan firms terrorized soccer grounds up and down the country, culminating in the fatal stabbing of a Blackpool fan. The Red Army’s antics—including a bloody at-sea brawl with West Ham supporters, on a ferry to Holland—led to crowd segregation. In ’77, based on its notoriously nasty following, Man U was even banned from European competition.

“If there was any sociology at all to it,” says Bill Buford, who embedded with hooligan firms for eight years to research his 1990 book Among the Thugs, “it was that they did it for no reason except it was fun.”

The beginning of the end of that fun came in 1989, at an FA Cup semifinal at Sheffield’s Hillsborough Stadium, where overcrowding led to a human crush that killed nearly 100 people. Police wrongly fingered hooligans in the aftermath (security’s own negligence was to blame, a jury later ruled), but the catastrophe still served as a wake-up call. Within a few years, it seemed, hooliganism had all but disappeared from English soccer.

The hooligans, though, were still out there, and in Salford, as much as anywhere else, elements of these groups evolved into street gangs. For years those gangs operated abandoned lots as unauthorized Old Trafford parking grounds—now they began expanding into more lucrative businesses. They needed to. Greater Manchester was struggling, especially Salford, where jobs were relocated to India as factories closed. Shipping moved toward larger containers, beyond what the canal could accommodate. In 1982, Salford’s docks, which decades earlier had employed 5,000 people, closed. Unemployment among young men ran close to 90%. Manchester became a symbol of the tough industrial city in decline.

It was this stew of hooliganism and down-and-out Salford angst that fed and nurtured Paul Massey. A magnetic fire hydrant of a man, with piercing brown eyes and a prominent nose, Massey had all the promise of a future Mr. Big: a streetfighter’s rash confidence, an innate understanding of how to maneuver in the shadows and a middle finger pointed squarely at authorities. All he needed was a big opportunity, equal to his dangerous potential.

That opportunity came in a yacht-builder’s shop on the other side of the shipping canal from where Massey grew up. In 1982, the managers behind two seminal Manchester bands, Joy Division and New Order, converted an old red-brick warehouse into a multifloor nightclub. The Haçienda hosted an era-defining roster of rockers, including The Smiths, The Stone Roses and Oasis. But that wasn’t really the scene for Massey and his hooligans.

Then New Order headed to the Spanish party island of Ibiza to record an album, in 1986, and that’s when “the whole club scene erupted, along with ecstasy,” says Peter Hook, New Order’s bassist. “We saw it. We brought people over to witness it. And we brought it back to Manchester.”

At first it was just once a week: an Ibiza-style “hot” night, with palm trees, ice pops and loads of pills, all set to the pounding beats of Chicago house music and Detroit techno. But that grew, and the Haçienda became the spot for 100,000 local university students. Knockoffs ensued. Manchester was the party capital of the U.K.

With the club scene thriving, “ecstasy exploded,” says Hook. “All these middle-class kids were selling drugs—£30 a tab. They were making s---loads of money. It didn’t take long for gangsters to spot what was happening.”

Massey would go to the Haçienda every weekend with Lydiate, who remembers the utopian bliss: new music, new drugs, new circles of people. Crowding thousands of ravers into a club, though, proved not to be the best business plan. Rolling on ecstasy, partygoers tended to drink water, not alcohol, to hydrate. One of the world’s most famous clubs was becoming a money pit.

Enter the budding Mr. Big. What made Massey special was his natural charisma. He was simply a charming dude. He had layers—more Tony Soprano than Scarface. In his own Salford way, he was a politician. His gangs weren’t strictly stratified; he was first among equals, like the so-called “top boy” in a hooligan firm. Nobody brought a crowd like Massey, who on any given night could turn out 100 or 200 people, says Peter Walsh, the author of Gang War: The Inside Story of the Manchester Gangs.

Which is how Massey and his Salford Lads gained control over the doors at the Haçienda, among other clubs. A throng of his men would overwhelm security, then go behind the bar and pour themselves drinks. It was a statement of intimidation: We own this place. Massey would hold a club hostage night after night until, eventually, the owners ceded control of the door to his new

PMS Security outfit.

“Raves were made for violent young criminals,” writes Walsh. “Older heavies were not interested; they didn’t understand the scene at all. It was wide open for the football hooligans. . . . The raves taught them a lesson some would use with a vengeance: Control the security of an event and you control who sells the drugs inside.”

Step 2 in Massey’s business plan: Command the ecstasy supply. As Walsh describes it, Massey and his associates would purchase the party drug in bulk at its point of manufacturing, in Amsterdam. The trick was in getting the pills past customs. The Salford Lads, experienced carjackers, would find British travelers who had driven to the Netherlands, break into their vehicles and stash a couple of bags of ecstasy, usually under the spare tire. A contact helped them access a government database that matched license plates with home addresses, allowing them to break into the car again and retrieve the drugs back in England, after the mark had driven home. Procured for a few pounds, each pill would sell in the U.K. for £15 or £20.

It all made for a flourishing business, hooliganism monetized. Massey’s guys raked in £10,000 a night from ecstasy sales alone. At one point, the Manchester Evening News reported that PMS Security had 120 men on its payroll, with an annual revenue of £1.7 million. The club scene, seedy underbelly and all, was a boon to Manchester. In the span of just a few years, this symbol of national malaise turned into one of Europe’s hottest party capitals: Madchester.

And in Madchester, Massey was king.

Just as the Haçienda spawned imitators, so did Mr. Big and his Salford Lads have plenty of competition. Gangsters with nicknames like Little Porky and Jimmy the Weed claimed allegiance to outfits such as the Cheetham Hill Gang and the Pepperhill Mob. And with competition came conflict. Assaults were reported regularly at clubs across Manchester. Doormen were stabbed. One pub landlord lost an eye in a beating. A rival made moves on the Haçienda, then found the head of his dog chopped off and laid out on the pool table at his home pub.

In the press, Madchester was now Gangchester. Or Gunchester. Or the Bronx of Britain. When Mike Tyson came through town to fight Julius Francis, the gang violence was so bad that Tyson was the one begging for peace in the streets.

Massey seemed to be getting arrested every other month, but he usually got off—the top boy typically keeps clean hands. In 1994 he helped broker a truce between two gangs, crystallizing his power. His security firm grew large enough and gained enough seeming legitimacy that it won contracts with the local government.

All good things, though, must come to an end. Especially when gangs and drugs and money are involved. In June 1997, the Haçienda closed its doors. “The gangsters had gone so f------ mad, you couldn’t guarantee people safety,” says Hook. “We had to give up.”

Now everything was coming apart. On the evening of July 4, 1998, Massey and his crew, at peak audaciousness, were showing off for BBC cameras, bouncing from club to club, swigging champagne from the bottle, when things went south at a Salford bar called Beat’n Track. A man was stabbed and nearly died. Mr. Big, the main suspect, was on the run to Amsterdam. Then extradited. And, just like that, it was over. Massey was just shy of 40 when he landed his stiffest prison sentence: 14 years, for “wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm.” Right in his prime.

The middle-aged hooligan who passed through the exit at Frankland prison in northeast England in 2007 presented himself as a changed man. He was by then a grandfather, and he said he wanted to give back to Salford. He spoke of opening a youth club. His security business, he claimed, was finally above board. The Salford Lads had been displaced by a new gang, the A Team. All that and, within a few years, he was a mayoral candidate. “I don’t want to be known as Mr. Big,” Massey told the Manchester Evening News as he submitted paperwork to run for Salford’s top office. “My campaign will be for everyone, regardless of class.”

Massey ran as a man of the people, a Robin Hood figure in a place that had no love for the establishment—but in the end he more closely resembled the old image of the unchangeable gangster. Just when I thought I was out . . . Mid-campaign, he was arrested for money laundering. When he finished seventh out of 10 candidates, he blamed the investigation, the same coppers who’d dogged him since childhood.

So as he aged into his mid-50s, Massey stayed close to the game. He became less of a street operator and more of an adviser, which is the role he was serving in July 2015, on holiday in North Wales, when he found himself mediating an increasingly violent gang war. On one side: the A Team, led by a Massey protégé, Stephen Britton, who had made the drive out to Winkups to talk about a spat that had started mundanely—a fight over a drink thrown at a nightclub, or over a fake watch; no one seemed to be sure—and then spiraled out of control. On the other side: the not-so-creatively named Anti-A Team, whose members had abandoned Britton for a young scaffolder named Michael “Cazza” Carroll. By the time Massey was pulled in, things had reached a boiling point. Masked men, presumably from the A Team, used a chainsaw to remove the roof of Carroll’s ex-girlfriend’s car. One A Team member was shot at close range while sitting inside his Mercedes. Another had his throat slit in a near-fatal machete attack.

In the old days, even after Massey ruled in a way that appeared sympathetic to one side, his word would have been gospel. But the Anti-A Team showed him no deference. “This wasn’t his generation anymore,” says Walsh. “There was a new generation, and they had their own rules.”

So there was Massey, walking up to his house with the Bacardi and Cokes, when shots rang out in his driveway.

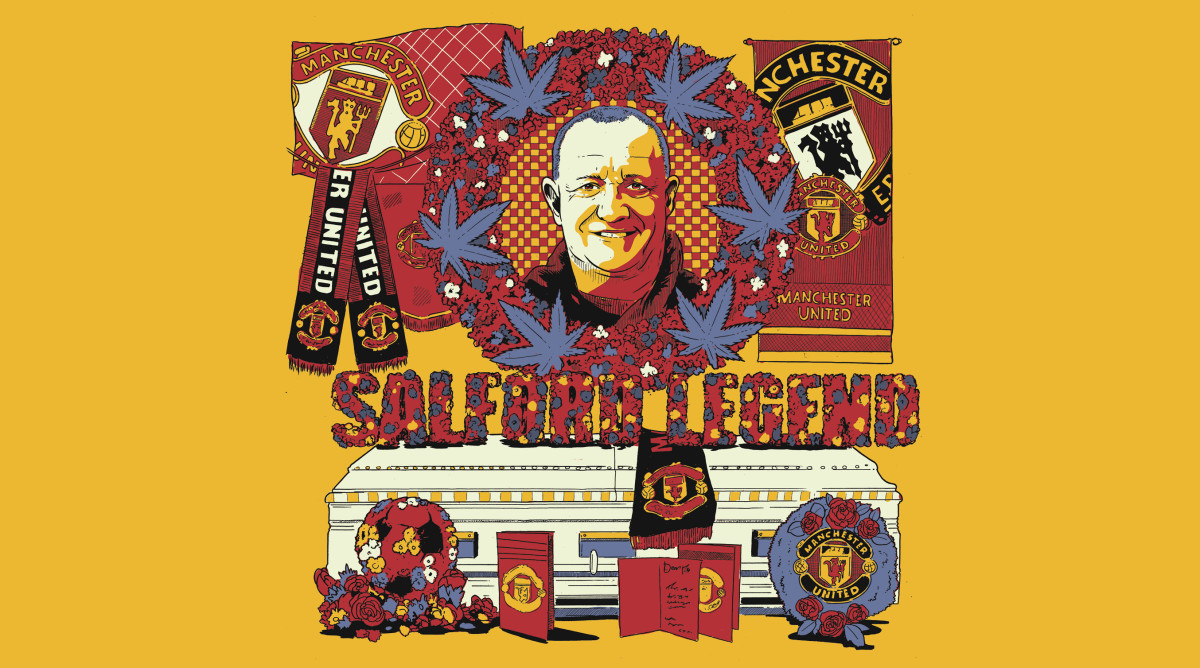

A month after his death, Paul Massey’s white casket—draped in Manchester United flags and cannabis-leaf-shaped wreaths—traveled to Agecroft Cemetery in a carriage pulled by six white horses, behind eight bagpipers, in a procession past thousands of admirers. Massey, reportedly dressed in his United reds and entombed with a stash of club memorabilia, was eventually lowered into the ground, at which point mourners tossed a handful of dirt on top, released 55 white doves and, finally, danced to one of Massey’s favorite songs from his Haçienda days: Joe Smooth’s “Promised Land.”

But gang wars don’t break to mourn. As attendees at the wake ordered their first drinks, they learned that an Anti-A Team member had been beaten at the cemetery with the wooden poles used to lower the coffin, and acid had been thrown in his face. One of Massey’s pallbearers, an A Team enforcer and old Salford Lads lieutenant named John Kinsella—or “Scouse,” for his Liverpudlian accent—was a suspect in the attack, according to the press.

The schism that cost Massey his life would continue. Carroll, the Anti-A Team leader, fled the country. Graffiti appeared throughout Salford, goading him to COME FIGHT YOUR WAR. One Anti-A Team member took a bullet in the butt. A wedding was interrupted by a smoke grenade.

Amid all this, authorities offered a £50,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Mr. Big’s killer. Fat chance. The code still ruled Salford. Police had linked 112 people to the murder, and none would talk.

Years passed. Officially, in the criminal justice system, Massey’s murder remained unsolved. Street justice, meanwhile, kept coming. A hit squad was dispatched to Spain to assassinate Carroll; the operation failed only when police raided an apartment in Marbella, seizing knives, a loaded pistol, a bat and a weighted vest, which, according to news reports, was to be used in sinking Carroll’s body in the Mediterranean. Authorities arrested several men in the plot, including Britton, the A Team leader, but he was eventually released. Carroll got away.

Salford, still, was silent. If there was a route to solving Massey’s murder, it would be an exceptional one. But no one had ever considered this possibility: What if the whole damn thing happened again? And what if, this time, the killer was a bit less cautious in covering his tracks?

An hour after sunrise on May 5, 2018, John Kinsella set out from his home, halfway between Manchester and Liverpool, for a morning walk with his pregnant girlfriend. Massey’s old friend was a martial arts expert, and, when a bit of muscle was needed, he was the A Team’s man. Key to his lore was an alleged incident in ’01, when he was said to have helped future English national team captain Steven Gerrard out of a messy love triangle involving a gangster known as the Psycho. Once Kinsella stepped in on the soccer star’s behalf, the Psycho stood down. Scouse was feared, seemingly untouchable, just like his old friend Massey. But as Michael Corleone observes in The Godfather Part II, “If history has taught us anything, it is that you can kill anyone.”

Around 7 a.m., as Kinsella’s six American bulldogs ran off-leash, his girlfriend heard the squeaking sound of bicycle brakes. She spun around and saw a man on a mountain bike—tall, slim and athletic, wearing a black snood, a ball cap and a neon high-visibility jacket over all-black clothing.

Then she heard a poof. And another.

Kinsella fell face-first to the ground. He’d been shot twice in the back, one of the bullets piercing his spine. As his girlfriend fled, jumping a fence and sprinting toward a nearby highway, she heard more gunshots.

The assailant cycled closer to Kinsella, stood over him and fired twice into the back of his head. “It was like a film,” Kinsella’s girlfriend would later say. “He wanted to finish what he was doing.”

And then Scouse’s assassin pedaled away.

It didn’t take a genius to link the killings of the gangland Godfather and his longtime Salford Lads associate, three years apart, in strikingly similar fashion. But gut feelings don’t get convictions. And as Manchester barrister Paul Greaney (who eventually led the case against Massey’s killer) reminds us: “There’s historically been a code of silence in Salford.” Gang spats are settled in the streets. Police needed to “prove [the] case without eyewitness evidence or people who [knew] what happened and why—with scientific evidence, or evidence showing the movements of the defendants.”

At first, all they had was a hunch.

Mark Fellows’s allegiance to the Anti-A Team was well known to authorities. He became a person of interest when he was shot in the butt shortly after Massey’s murder. But he was never taken into custody. His rap sheet was that of a low-level criminal: By age 38 he’d been convicted five times for offenses ranging from robbery to unlicensed possession of ammunition. Nothing, though, that would suggest assassin.

With a blocky chin and a lithe runner’s build, Fellows looked more like an accountant than a hit man. The Salford native seemed to live a quiet life. He wore a colostomy bag from a childhood illness, and he was finicky about his hygiene and health. He had two young children and worked overnight shifts as a sous chef, preparing sauces for a manufacturer of chilled and frozen foods. He was also an avid distance runner, timing his outings with a Garmin Forerunner 10 GPS watch. He had recently checked off the 10K portion of the Great Manchester Run (in a brisk 47 minutes), and official race photos captured him as he neared the finish line, hair tousled, with a tank top over a long-sleeved running shirt, the Garmin attached to his left wrist.

As police searched for clues in Kinsella’s shooting, they unearthed CCTV security footage that captured not the murder itself but a man on a bicycle, his face obscured, pedaling toward Kinsella’s home around 5 a.m. And that man, they found, looked much like Fellows. So, on May 30, 2018, authorities boarded an easyJet flight arriving at Manchester Airport from Amsterdam and arrested him on suspicion of having committed both murders. At the station, police tried to interview the figure known in gangland circles as the Iceman, but he stayed silent.

The case against Fellows was far from airtight, but police did find in his possession a suspicious smartphone that had been modified so that, if turned on by pressing the power button together with a volume button, it could enter an encrypted mode. “These are not the types of phones that can be bought from Carphone Warehouse,” a prosecutor would later tell a courtroom, suggesting that this was the type of device a hit man would use to communicate with a spotter.

In short time, that suspected spotter was arrested, too. Stephen Boyle, prosecutors would allege, was a friend and associate of both Fellows and Carroll; he’d trailed Massey in a car after the Bargain Booze pit stop back in 2015, and he was lying in wait in ’18, signaling the Iceman when Kinsella and his dogs approached.

Like Fellows, Boyle, at 35, had a litany of small-time convictions. In that way, he was a typical Salford thug. In this way, though, he was not: Boyle opened his mouth. “I haven’t murdered anybody,” he told police when they arrested him at a hotel outside of Manchester, “but I probably know more things about it than I should.”

While Boyle’s tease was shocking, it wasn’t enough. Police needed hard evidence to box him in—that was the goal when they raided Fellows’s flat, searching for anything that could link him to the murders. They didn’t find the bicycle from the CCTV footage. They didn’t find a murder weapon. What they did find was a mundane piece of evidence that, in concert with a loose-lipped gang member, unspooled both cases: the Garmin Forerunner 10 GPS watch.

Investigators downloaded data from the device and found that Fellows had used it to track not only his runs, including the Manchester 10K, but also a series of reconnaisance missions. (He had the foresight to not use the watch as he cycled to and from the actual murders.) On one such outing, three months before Massey was killed, Fellows had traveled from his home in Salford to the field across the street from Massey’s house. The watch recorded speeds that suggested a man on a bike, not on foot, and noted that its wearer had manually stopped recording his location while he stood by the small stone church. He spent eight minutes there, having “found his spot, and found his escape route,” Greaney would later say at trial.

And then he pedaled away.

The joint trial for the murders of Paul Massey and John Kinsella had as intense a security presence as any case that its prosecutors had ever witnessed. Liverpool Crown Court banned the jury from being photographed and forbade mobile phones.

Inside, over the course of six weeks, the prosecution argued that Fellows had been paid to carry out both hits, and that Boyle had assisted each time. Fellows’s lawyer did not call any witnesses, but the defense for the Iceman’s alleged spotter called Boyle himself, and here Boyle again did the unthinkable. On the stand, he claimed that he’d played no part in the Massey murder. In Kinsella’s case, however, he said he was along for what he believed to be a drug deal—then Fellows killed Kinsella and handed him a revolver, tucked in a sock inside a backpack. Boyle testified: “I was like, ‘How can you do that to [me]?’ ” He said he hoped that Fellows, ultimately, would confess and admitted that he now feared for his own friends and family.

The prosecution scoffed at Boyle’s defense. The jury, at the very least, didn’t buy it. After 31 hours of deliberation, the 12-person panel found Boyle guilty in Kinsella’s murder. (He was cleared in Massey’s homicide, for lack of evidence.) His life sentence allowed, potentially, for parole after 33 years, in 2052. Fellows, guilty on both counts, got the same, without the possibility of parole—an exceedingly rare penalty in Great Britain that ensured he would die in prison—as well as the judge’s stiff rebuke: “I have never had to deal with a contract killer of your kind before.”

Fellows smirked while the sentences were being read. As guards led him from the dock he reportedly made a throat-slashing gesture and spoke directly to his codefendant, telling Boyle: “It’s your f---ig fault, you f---ing grass.”

The court had done its part, but street justice still had to be meted out. Barely a month after his conviction, Fellows was at Whitemoor maximum-security prison, 150 miles southeast of Salford, when a Liverpool gang member slashed him with a wooden block that had been tightly packed with five razor blades. The Iceman was airlifted to a hospital and left with severe facial injuries.

Less than two years later he was charged in two more attacks on A Team members, each predating Massey’s murder: the shooting of the man inside the Mercedes, for which he was eventually cleared; and the machete incident, for which he was found guilty, based partly on CCTV footage that captured him conferring shortly before the attack with Carroll (who is rumored to have fled to Dubai). For the latter conviction, Fellows received yet another life sentence.

When Paul Massey was at the height of his powers—Mr. Big, the king of Salford—he spoke to the BBC about where he drew his moral line. “I’m not interested in killing people,” said the gangster who would later be jailed for stabbing a man. “I’ve seen what devastation it causes to the family that you leave behind. Them families are never going to get over it.”

Massey’s family has not gotten over it.

Louise Lydiate never moved back into that red-brick home; the memories of her partner’s murder were too heavy. She took a job managing a small, run-down pub in Salford, where she lived upstairs. She knew the regulars. It felt like family, and like therapy. But she tended to stay up until the last drinker was out the door, then woke early to clean, and it wore her down. She drank too much. Customers noticed. “I can’t do [that] to my family and my kids,” Lydiate says. “They been through enough already.”

She quit the pub job and moved into a small two-bedroom apartment in the heart of Salford with her two chihuahuas, Pippa and Rolo. Six years later, she still thinks about Massey’s murder constantly. She’s taking anxiety meds for the first time in her life. She says she suffers panic attacks and nightmares and has been diagnosed with PTSD. Her initial anger has given way to an all-consuming sadness. She has spent untold hours wondering why her partner was gunned down not at age 30, when he was in the thick of the gang wars, but at 55, when that life seemed behind him.

In Lydiate’s living room hangs the last photo taken of her and Massey, at a restaurant in Wales, a couple of days before he was killed. Every night, she talks to the picture. She’ll ask what Massey thinks about her life now. What would Paul want me doing? She doesn’t know what he would think of her living alone. Sometimes she can almost hear his voice. Get over it, she hears him say. Get on with your life.

Ghosts are complicated. They still hold secrets. But, stripped of ego, out of the race, they can see themselves and their adversaries in full. They can be honest.

So, what would the ghost of Paul Massey have to say about the man who murdered him? He’d want vengeance, certainly. Would he also, perhaps, hold a grudging respect? For the efficiency. For the discretion. For the adherence to a code. Even after he was arrested, Fellows didn’t talk to the police. On trial for his life, he never testified.

He stuck to that refracted sense of morality that defines a Salford lad.

• Colt Brennan: ‘They Did Everything, But Nothing Could Ever Save Him’

• He Rose to the Highest Levels of Business and Basketball—but With a Secret

• Inside the Quest To Prolong Athletic Mortality