Can This Soccer Team Save the Planet?

It’s an odd spot for the future of sports, tucked away atop a hill in the English countryside, two hours west of London. Nailsworth is a quaint little town with a population just north of 5,700. Cottages dot the rolling landscape, bordered by stone walls and neatly manicured hedges and lush green trees with mushroom-shaped tops so thick and perfect they look like an artist’s rendering. On the drive into town on this sunny but brisk October morning, a cow stops in the opposite lane, shuts down traffic and refuses to move, despite the honking protests.

I ask our photographer, Tom—a delightful lad from London who kindly shuttles us both out here so I don’t have to drive on the left side of the road, thus avoiding an international incident—what he’d do if he lived in a place like this.

“I guess I’d play a lot of golf.”

“Do you golf?”

“No, but you’d have to take it up, wouldn’t you?”

All of which is to say that Nailsworth is not without its charms. But it’s an unexpected place for a professional sports team that has garnered global attention. That squad, Forest Green Rovers, has dubbed itself the greenest soccer club on Earth—and everyone agrees, from the big boys two levels up in the Premier League to the United Nations, which certified FGR as the world’s first carbon-neutral club.

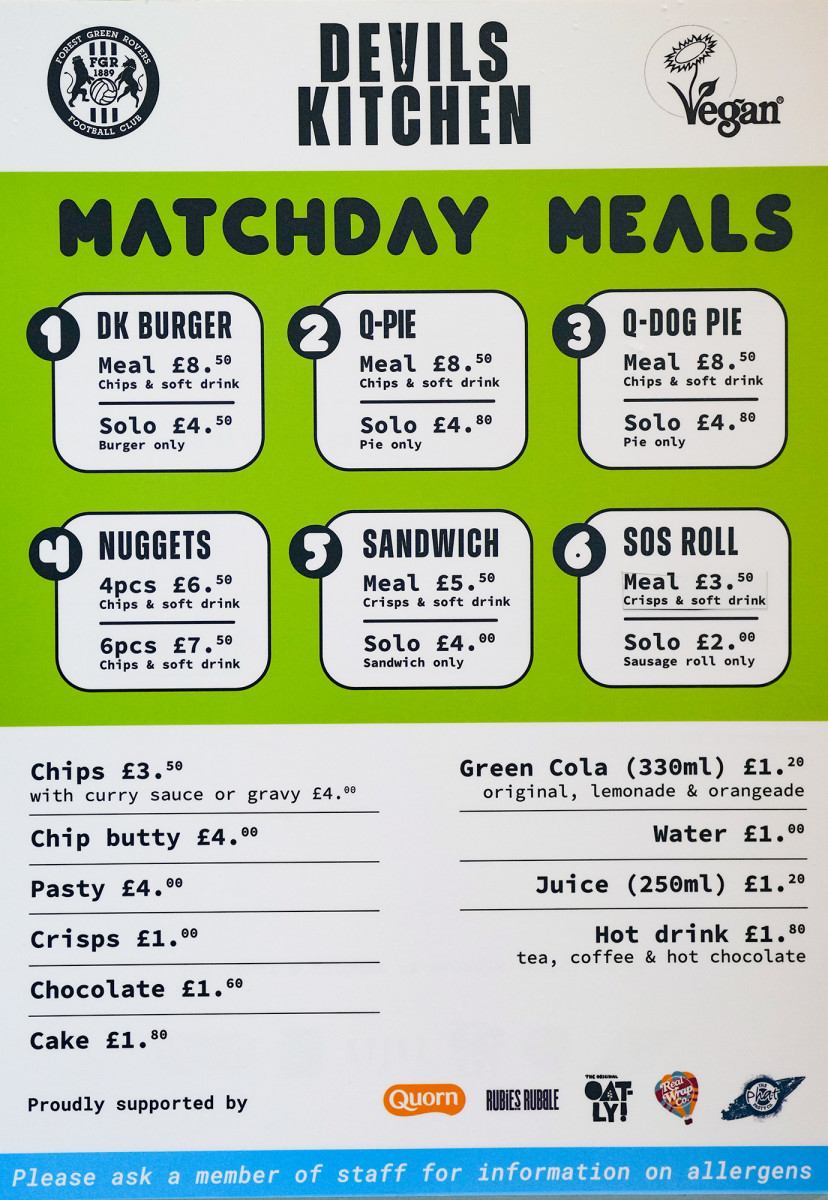

The pitch at The Bolt New Lawn stadium is fertilized with seaweed. There are charging ports for supporters with electric vehicles. Some 20% of the electricity for the entire operation comes from solar panels mounted on the stadium roof; the rest is supplied by windmills just up the hill and behind a bank of trees overlooking the grounds. The soda machines use carbon-capture technology to fizz the drinks. The jerseys are made from coffee grounds and recycled plastic. The club is building a new stadium nearby entirely out of timber (concrete is environmentally unfriendly for a host of reasons), and by next season the team hopes to train at that location. The cooking grease used at the concession stands is recycled, and the food itself—burgers, nuggets, sandwiches and hand pies—is entirely vegan. Oh, and the hydroponic lights used for growing the grass on the pitch were confiscated by the local constables in a drug raid. Even they’re recycled, in a way. What else?

“We have one of those solar-powered lawn-mower robots,” the team’s owner, Dale Vince, tells me as we tour the grounds before FGR takes on Bolton this afternoon. “Just goes ’round the pitch. But we’ve had that for like 10 years now.”

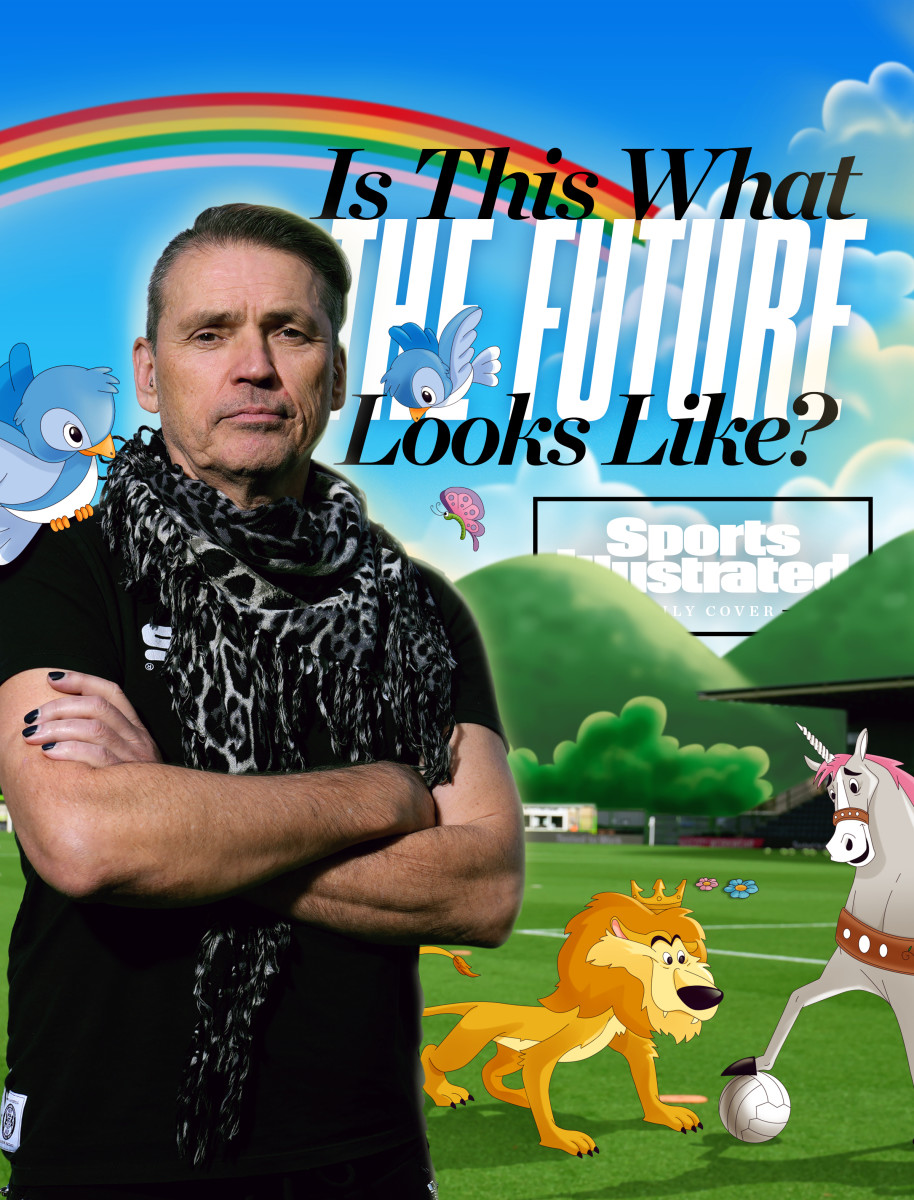

Vince, 61, is tall and trim, with his head shaved on the sides and wisps of long sandy hair flowing straight back. He’s wearing a black-and-white scarf, black T-shirt and tight black pants with zippers stitched in random locations. His fingernails are painted black, and he has a little lightning bolt earring punched into his cartilage.

He’s held forth today on everything from his excitement about an electric plane project to the various political controversies he’s set off in recent weeks. Right now, though, he’s telling me about a new technology developed by the green energy company he founded, Ecotricity, in which lab-created carbon is used to make diamonds. Evidently FGR draws a ticket number and hands one out to a lucky fan after every home game. The stones are worth a couple thousand pounds, according to FGR’s PR director, Will Guyatt. Which, again, sounds outrageous, that this man—who has been described to me as a less-wealthy Richard Branson, but who reminds me, too, of a slightly older but equally eccentric Russell Brand—is just printing diamonds somewhere. But then again the jerseys are made of coffee grounds, and who knows where the snozzberries come from.

“He’s a little like a green Willy Wonka,” Will the PR man says.

How is it that something like this exists at all, let alone in English cow country? And how have the supporters of this club, founded 133 years ago, responded to a man who took over their local team and turned it into something so . . . different? Some 3,400 people attend today’s match, and they’ll go home smiling after a surprising 1–0 win over Bolton. (FGR got promoted this season to Football League One, two rungs below the Premier League, which was a happy occurrence, though the team has spent much of this first campaign at the bottom of the table, on its way to being relegated, which has been less pleasant.) They certainly seem to enjoy the experience, with their vegan food and solar-and-wind-powered grounds, but I’m uncertain about whether they took to all the eco-friendly measures straight away.

Like so many people I speak with in England, I want to know how scalable FGR’s operation might be. Would it work in the Premier League? The NFL? Could this tiny club in this tiny town actually be a preview of a more sustainable future in sports? More to the point: What exactly has Green Willy Wonka built out here, anyway?

It was dicey in the beginning. A little over a decade ago, Forest Green was in bad financial shape. The club needed someone to ride to the rescue. Vince became that someone.

He’s a lifelong soccer fan who still plays pickup. He lives in Stroud, just north of Nailsworth, and the first commercial windmill he built, back in 1995, still sits atop a hill a few hundred yards beyond FGR’s grounds. Years before that, Vince lived up there in, as he puts it, “trucks and buses and things.” He used a personal “little windmill to power my life with some old train batteries from the scrap yard. So I was kind of self-sufficient.”

Vince grew up in Great Yarmouth, on England’s east coast. His father ran a small trucking business, but the family wasn’t rich by any definition. Vince quit school at 15, tried college for a while later on, then dropped out. From around the age of 20, he lived on the road.

Sustainability had always been his kink. Still is. And by 2010, when FGR was in danger of going under, Vince had harnessed his passion to become a successful businessman. That first windmill he built turned into several, then many, and eventually he started Ecotricity, “England’s greenest energy company.” After that came the Electric Highway, the country’s first national charging network, which he sold in ’21 for some £85 million. (He’s pegged his net worth at somewhere slightly north of £100 million.) Not long ago he decided to sell Ecotricity, to get into politics, but shopping the company hasn’t gone as well as expected. For now, he’s keeping it. He still plans to be involved in politics, mostly through the creation of a think tank to produce studies for the government about becoming greener. He’s already doing a bit of that, informally. He went to the Tory conference in early October in hopes of lobbying (and needling) lawmakers. Vince secured a media credential for the event because he imagined that the U.K.’s conservative party would not be thrilled about him attending. He’s a regular contributor to the Daily Express on environmental concerns, and the outlet happily issued him a press badge, which he plunks down on the table to show me. When I suggest that now he knows what it’s like to be a hated member of the press, he chuckles and says he gets plenty of hate regardless.

In March 2022 a game between Everton and Newcastle was halted when a protester representing Just Stop Oil—the same group that last fall threw soup at a Van Gogh painting in The National Gallery in London—zip-tied his neck to a goalpost. Vince had donated cash to the organization, so he caught heat. He says he didn’t know they were planning to interrupt a Premier League match, but he didn’t seem too broken up about it afterward. He calls it “amusing” to be incidentally linked to the flap and says he supports the movement to stop oil exploration and production.

That’s merely one of his well-publicized controversies. In addition to a pirate flag and a green version of a British flag, the Palestinian flag flies over FGR’s pitch, at Vince’s request. It went up more than a year ago when Russia invaded Ukraine. Vince says that all the things that were being visited upon the Ukrainians—the unjust occupation, the violence, the loss of life and the human rights violations—were happening to Palestinians, too. Many took umbrage at the way he linked the conflicts; critics have labeled him anti-Israeli, antisemitic, or both. A group called UK Lawyers for Israel called for FGR’s sponsors to dump the team and, in at least one instance, had success. Vince says he is not antisemitic, nor anti-Israeli, nor does he question Israel’s right to exist, but he is critical of some of its government’s policies. The flag is still up.

All of which is a long way of saying: Vince is down for a cause. Forest Green was another outfit that needed help; otherwise it would likely have had to fold. He didn’t want to run a football club, but he figured the team “is in my backyard. I can do it, so I will do it.” He took on the club’s debt of a few hundred thousand pounds, and that was that. Suddenly he owned Forest Green Rovers.

Which does not mean that Vince immediately won over the suspicious FGR faithful. He believes his performance in a charity match not long after he took over, between Forest Green alums and some actors from Hollyoaks, a British soap opera, went a long way. “I came on and scored the f---ing winner with a diving header. The ball was down here somewhere,” he says, motioning toward the floor with his palm. “It was an epic goal. And you couldn’t ask more than that, right?”

He’s laughing now. It’s a fun yarn, and it probably bought him some good will. But epic charity headers get the new guy only so far, especially when the new guy wastes no time turning FGR upside down. Changing how the team operates to align with his principles wasn’t just part of Vince’s objectives. It was the whole point. He calls the club “a rescue mission that turned into a massive opportunity.”

He was primarily focused then—and still is now—on three things: energy, transport and food, which together he says “make up 80% of everyone’s carbon footprint.” He has always preached that people shouldn’t wait for governments and big business to lead the way. With FGR, he had the literal means to put his money where his mouth was, and his mouth was precisely where he started.

When he bought the club, Forest Green was serving beef to fans and players. “That made me part of the meat trade,” he says. That was the end of meat at FGR.

“It’s still the thing that the media want to talk to us about first when they come to see us,” Vince says. “And we’ve been doing it for more than 10 years now. They’re still like, ‘How can you run a sports club that’s vegan and not have a fan revolt?’”

I did not ask that question—not specifically—but I did wonder about the initial reaction from fans and whether it gave Vince pause.

“I don’t want to say I disregarded what the fans thought. It wasn’t that,” Vince says. “I wanted the fans to come with. But there was never a question of ‘I won’t do this or that if the fans won’t come with me.’ I would have walked away from the club if I couldn’t do this or that, because I couldn’t be a part of something that I didn’t believe in completely. So we set about making those changes—but in the process we took care to explain to our fans not just what we were doing but why we were doing it. And we tried to show them that these were changes that they could make at home by themselves.”

That messaging—how to explain sustainability and various environmental measures to the average fan—is at the core of what Vince is trying to accomplish, and it is a never-ending topic at the Sports Positive summit we both attend in London in days before the Bolton match. Held at Wembley Stadium with the backing of the UN Climate Action organization, the conference features academics and business people interested in where sports and sustainability meet, including top executives from the EPL, NFL, NBA and Formula E, a Formula One–style circuit with electric cars.

“I think we can hijack, for lack of a better term, fan identification,” says Brian McCullough, host of one of the conference’s panels and an associate professor of sports management at Texas A&M. He’s a big fan of what Vince is doing—

specifically using FGR to make fans think about these issues. McCullough believes messaging is crucial. The tribalism of sports can be harnessed, he says, to “get past the gatekeeper that would say, ‘No, this is what the Democrats want.’ Or, ‘No, God will take care of everything.’ You can get past that. It’s the [Dallas] Cowboys telling me I need to do this. And because Jerry Jones is telling me, I’m gonna do it—because I am a die-hard [Cowboys] fan.”

Forest Green is obviously smaller than the Cowboys, and Dale Vince is no Jerry Jones, but FGR provides at least a glimpse of how this all might work. Which brings us back to the food. Vince acknowledges that “we did face a little opposition to start” because “food is a very emotive topic” and “people can feel threatened when you appear to challenge their choice of what they’re eating.” But ultimately, when it comes to the concessions, he says, “We haven’t found it to be that difficult.” He says the key is simple. “We make great food.”

Vince explains: “We say to our fans, ‘Come and try it. If you don’t like it, you can bring your own. We really don’t mind.’ But we’re serving the food that we believe in and we can’t serve anything else.”

I don’t hear many complaints. Before the Bolton match, a father named James Preece has just finished his vegan burger, which he calls “very tasty.” He’s sitting at a table with his teenage son, Sam, and Sam’s two friends, Callum and Dan. The kids are all tucking into vegan nuggets and chips, which they say don’t taste like chicken—but that’s O.K., because they all agree they’re pretty good anyway. Plus, Callum offers, “The environment has really gone downhill at the moment, and I think it’s good that someone wants to make it better for us.” He’s 13 going on 40.

A lot of clubs have come through to tour the Nailsworth grounds since Vince became Forest Green’s majority shareholder. But none have stopped selling meat—or equaled Forest Green in reaching carbon net zero. As Wimbledon CEO Sally Bolton candidly tells the audience at the Sports Positive conference, “We’ve found that the cost of doing things in a more sustainable way is just more expensive.” But what might it look like if one of the bigger clubs tried?

On the day after the NFL (finally) put on an entertaining game in London in early October—a down-to-the-wire thriller with the Vikings sneaking past the Saints—and a few days before FGR faces Bolton, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium hosts an event called NFL Green. It’s a gray, gloomy afternoon in North London, and about 40 people from around the world are here for a discussion about sustainability in sports.

“Welcome to the greenest stadium in the world,” Tottenham PR director Tony Stevens tells us as we tour the facility. Spurs were tied with Liverpool last season atop the Sports Positive Premier League sustainability table, a ranking of the 20 clubs based on 11 categories, including energy and water efficiency, waste management and sustainable transport.

The stadium opened in 2019 and holds just shy of 63,000, making it the third-biggest ground in England. Part of the stadium’s appeal is making it easy for all those fans to get here. The facility is practically a corner kick away from the White Hart Lane overground stop, you can walk to Seven Sisters tube station in about 30 minutes and the club incentivizes fans to bike to the stadium.

When it comes to sporting events, the most vexing issues for environmentalists are the ones beyond an organization’s direct control. How fans travel to games is high on that list. The transportation of equipment and people, in general, is a huge problem. As Julia Palle, Formula E’s sustainability director, concedes at the Sports Positive conference: Electric cars are great, but “we still need the boats and we still need the planes [to move the cars and the people]. Seventy-five percent of the footprint for us is this.”

There are no easy solutions here, but as multiple people tell me, “You have to start somewhere.” That’s probably the best way to sum up Tottenham’s efforts. Spurs still sell meat, but Stevens says the club has seen a 50% increase in plant-based food purchases on match days. Like most teams, Tottenham sells a lot of beer, all of which gets poured into reusable cups. Reusable cups are different from recyclable cups because they don’t have to be shipped to a facility, broken down, then refashioned into cups again. Instead, special bins instruct fans on how to deposit the pints they’ve pounded. Tottenham processed some 27,000 reusable cups for the Saints-Vikings game alone.

The stadium has partnered with a local craft beer company, Beavertown, to run its own on-site microbrewery—I can vouch for the Neck Oil IPA—which reduces the mileage otherwise required to ship in suds. There’s also a circle-of-life component. Stevens tells us the mulch from the brewery is taken to a farm in Essex, where pigs consume it; later, those pigs become stadium sausages.

Tottenham also has an on-site bailer for cardboard, and there are seven ecobots that supplement stadium workers and help clean the largest concourse areas. On the whole, Tottenham seems fairly far ahead of the other EPL clubs, not to mention most NFL teams. Some of those are better than others. The Philadelphia Eagles, who installed solar panels on Lincoln Financial Field, are frequently mentioned as one of the NFL’s sustainability leaders. Most U.S. teams lag pretty far behind, though, and experts like McCullough complain that many have oversold their environmental contributions.

It seems highly unlikely that any Premier League or NFL team will go full Forest Green, but whether it’s even possible is an interesting thought experiment.

“They’re great and they’re genuine, but [they’re] much smaller,” Stevens says of FGR. “The bigger the level, the bigger the club, the harder it becomes.”

Vince naturally disagrees. He thinks it would be easier, not harder, to implement FGR’s framework in the EPL, for the same reason so many others seem to think it’s impossible: money. For the world’s richest soccer league, where transfer fees can stretch into the hundreds of millions, writing fat checks for fancy toys never seems to be a problem.

“Money’s really tight in the lower leagues,” Vince says. “It’s not tight in the Premier League. I think it’s easier the higher up you go.”

Vince figures the proof of concept is in what FGR has done. He points out that the club has reached an audience that extends beyond Britain, including 100 or so self-formed fan clubs globally. “There are billions of sport fans around the world,” Vince says, “and if we can reach them and make them fans of the environment, that’s a massive opportunity to change which way the world goes ’round.”

He’s certain that his model would scale. To Vince, it’s not a question of “If you build it, will they come?” The way he sees it, he built it, and they’re already coming.

Ollie Jones grew up in England in the ’80s, a stretch of soccer history perhaps best defined by Bill Buford’s seminal tome about hooligans, Among the Thugs. A Sunday Times piece of that era famously described football as “a slum game played by slum people in slum stadiums.”

Maybe Jones wouldn’t go that far, but he’d agree with the underlying sentiment. The violence and the atmosphere back when he was a kid weren’t for him or his parents. He didn’t have a club and he didn’t watch much. As an adult, he moved abroad. Now, for work, he helps governments with water management. It’s a job that’s taken him all over the world—Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, India and Ethiopia. He moved back to England with his family eight years ago. They live in Cirencester now, about 20 miles from Nailsworth. Ollie’s kids didn’t have a club, but they wanted one, so Jones started taking the kids to Forest Green matches. Before long, they were hooked. Working in water, Jones was intrigued by FGR’s sustainability push—but he likes the family-friendly environment most. Lots of children attend matches, and, after one of his sons won the local league with his team, Jones rang up FGR and informed them. The club had the youth team come to a match and lead the Forest Green players onto the pitch, and the parents all got their tickets comped.

When it comes to local FGR fans, Jones says there’s a mix of people like him who are into environmental issues; he describes Nailsworth as having “quite an alternative community.” And then there are others, from more conservative areas, “loads of people where this wouldn’t necessarily resonate with their lives.” And yet, as far as Forest Green’s eco-friendly measures go, Jones says “there seems to be no real pushback among the fans.” He doesn’t know how many of his fellow FGR supporters have converted to veganism—he hasn’t—but the food lines are usually long, and the stands are mostly full. Jones took the family to the Salford match last season, and some of their supporters showed up wearing hotdog costumes to heckle the hosts. Everyone had a laugh.

“No one is taking it too seriously. It was amusing,” Jones says. “There’s an appreciation of it. People recognize it. I don’t hear too many disgruntled voices. I think people vote with their wallets, and they’re still coming.”

Which is Vince’s point. He doesn’t believe EPL or NFL fans would stop watching either brand of football if franchises mimicked FGR. But then again, those organizations are largely owned by billionaire businessmen, not crusaders. And asking them to have tighter margins is blasphemous, given their devotion to making gobs of money. There’s always going to be a customer who isn’t interested in the environment and who just wants to watch their sports and not be bothered. As long as those very rich owners can get richer by selling that fan their cow burger and leave them to watch their sports, that’s the path of least resistance, and greater profit.

Vince knows as much, though he doesn’t excuse the big clubs for not doing more. He thinks they’re content with anything that might get them positive PR, like the game between Tottenham and Chelsea in December 2021 that was billed as the world’s first net-zero carbon match among elite clubs. Vince snickers at the “elite” qualifier, because, he says, “They know we exist. We don’t just have a zero-carbon game, we have a year of it—everything we do.”

When I push back that Tottenham has taken some steps in his direction—as everyone all week keeps saying, you have to start somewhere, right?—he allows that they’re trying. And, he says, at least they’re better than Manchester United, a club that was crushed in 2021 for flying its players 100 miles to a match against Leicester City. (It should be noted: East Coast teams in the U.S. do this all the time, and nary a peep is heard about it.) To Vince, that’s indefensible. As best he remembers, the last flight he took was back in ’18. When he travels now, it’s mostly by electric vehicle or train. It took him two days to reach Arnold Schwarzenegger’s climate conference in Austria last summer (where he delivered Arnold an FGR shirt). Bully for him, but avoiding air travel is unrealistic for most of the world, particularly top-flight soccer clubs. That’s a point Vince concedes, while insisting that everyone needs to do better—even Tottenham.

“Not saying [Tottenham isn’t] good,” Vince says as he sips a pint before the Bolton match. “I’m saying they could be an awful lot better. It’s not like they don’t have the money. Have they got solar panels on their roof? Nah. I’m not criticizing them. They have made a start.”

O.K., so you’re in charge tomorrow. What changes?

“Of what? Tottenham?”

Tottenham. What happens?

“Everything happens. Everything we’ve done here.”

Stevens, Spurs’ PR director, wonders for his part what might happen in an alternate universe where Forest Green keeps moving up and somehow secures a Ted Lasso–like promotion to the Premier League. Vince is amused by the idea and jokes, “We’re coming for them. Tell them that.” But he knows that’s unrealistic. FGR’s goal is to play in the Championship, one level below the Prem and one above where Forest Green has competed this season. “It’s still hugely ambitious, but it’s doable,” he says. “The Premier League, there’s more ambition than realism in that.”

That doesn’t mean Vince will stop “coming for them” in other ways, pushing the Premier League to do more on sustainability. The people at Tottenham seem to understand that, and they don’t appear too bothered by his approach. Actually, Spurs employees have great things to say about FGR and Vince.

“Do they?” Vince asks, a smirk forming as he presses his green thumb into the Premier League’s eye for one more laugh at their expense. “Well, don’t let me slag them off in your piece then.”