The Future Is Now for the USWNT

For as graceful and agile as she is on the pitch, Naomi Girma is surprisingly clumsy as she grips the foreign object she’s just been handed. She turns it over in her palms and stares at it. “So I just roll it and go?” she asks uncertainly.

Forward Sophia Smith grabs it and tries to help. “You have to scroll it,” she says, pointing.

A crowd gathers as Girma continues to struggle. “She was born in the 2000s,” someone says.

Finally, U.S. women’s national team content manager MC Barrett, who was born in the 1990s—and whose fault it is that they’re having this conversation in the first place—steps in.

“You turn it,” she explains. “See how you’re on 27? Then you hit it, and once you take a picture, you crank it and it drops down.”

Girma, 22, laughs. She is the future of the USWNT’s defense. But the anticipatory skills that usually help her on the field don’t quite seem to translate. “You picked the wrong girlie,” she says.

In Barrett’s defense, on a team as young as this one, it’s hard to find anyone who knows how to use a disposable camera.

There has been a lot to document already as the USWNT charges—and sometimes limps—toward this summer’s World Cup, where it hopes to capture its third straight title and fifth overall. This quadrennial has been marked by a changeover in coaching, from Jill Ellis to Vlatko Andonovski; a pandemic; a bronze medal at the rescheduled Tokyo Games, only the second time the squad failed to make the Olympic title game; the retirement of forward Carli Lloyd, a fixture since 2005; a series of firings and resignations as National Women’s Soccer League coaches and executives received punishment for either perpetrating or mishandling alleged abusive misconduct; a settlement in the lawsuit players filed against U.S. Soccer demanding equal pay; and a flood of injuries that have left the U.S. short-footed.

And the faces have changed. At least half of the players set to travel to Australia and New Zealand will be making their World Cup debuts; many will have 30 or fewer caps. The next generation of the USWNT is here.

When the team entered its two April friendlies against Ireland—the second- and third-to-last matches before the World Cup—it was already working around several key absences. Defender Abby Dahlkemper (back); midfielders Catarina Macario (torn ACL) and Sam Mewis (two knee surgeries); and forwards Tobin Heath (knee surgery), Christen Press (torn ACL) and Megan Rapinoe (calf) were all out. Midfielder Julie Ertz (parental leave) and defenders Casey Krueger (parental leave) and Tierna Davidson (torn ACL) were making their 2023 national team debuts.

The results had been uneven to that point. Last fall the Americans lost three straight games for the first time since 1993 and snapped a 71-game home unbeaten streak that spanned more than five years. But they swept the three-game SheBelieves Cup in February, playing against teams—Japan, Brazil and Canada—with very different styles. And as the patchwork roster started to jell, coaches and players alike began to grow more and more excited.

They were buzzing about one player in particular: Mallory Swanson.

Swanson became the youngest senior national teamer in a decade and a half when she debuted at 17 in 2016. Seven months later, in Rio, she became the youngest player ever to score an Olympic goal for the U.S. In ’19, she was the second-youngest player on the World Cup roster. But beset by injuries and facing adversity for the first time in her career, she began playing inconsistently and did not make the roster for the Tokyo Olympics.

Rather than feeling slighted, Swanson accepted this setback as a challenge. She increased her level of intensity on the field and began working with a sport psychologist off it. She had spent most of her career as the kid surrounded by grown-ups, but now coaches began to rely on her both as a player and as a leader.

By April 2023, Swanson had become the player everyone knew she could be. She scored in six straight USWNT games, including seven goals in the first five games of the year, matching her career high for a season. At 25 years old, Swanson was reaching a turning point in her international game, becoming a true leader on a squad of even younger stars—all at the perfect moment ahead of the World Cup.

But in Austin, 40 minutes into the first April friendly against Ireland, Swanson took a pass and sustained a hard tackle from Irish defender Aoife Mannion. She yelped in pain and remained crumpled on the grass as trainers tended to her and a sellout crowd of 20,593 at Q2 Stadium chanted her name. As she was stretchered off, she lifted her hands in the shape of a heart.

The team announced the next day that she had torn her left patellar tendon; two days later she underwent successful surgery. But with a recovery timeline that typically takes six months, barring a scientific miracle, Swanson will watch the World Cup from her Chicago home.

Her absence changes the dynamic on and off the pitch. Swanson was the player most likely to embarrass opposing defenders; she was also the player most likely to send her teammates into giggles by tripping over her own feet. Andonovski—who is 49-5-6 since taking over as coach in October 2019—had planned to build the team around Swanson on the left wing and Smith on the right; now he will have to reshuffle his attack, often on the fly. But the U.S. system is designed to slot in ever-younger players to a structure strong enough to incorporate them.

“We all understand that we have a job to do,” Andonovski said before the second friendly against Ireland.

While there is no replacing Swanson, who would have had a chance to win the Golden Boot in Australia, the U.S.’s options at forward border on absurdity. “We have so many different weapons to use,” midfielder Rose Lavelle said two days before Swanson went down. “I laugh sometimes, because I’m like, if you sub [Swanson] out, now you have [forward Trinity Rodman] coming in. Or you sub Trinity out—just the depth that we have, especially with the young group, is incredible.”

Smith, the 22-year-old reigning U.S. Soccer Player of the Year and NWSL MVP, led the national team with 11 goals in 2022 and is playing at a similar pace with the Portland Thorns so far this season. Rodman, who came on as Swanson’s substitute immediately after the injury, is also on the rise. The 21-year-old has seen an increased role with the national team this year, having already surpassed her minutes played in all of ’22.

And they are not even Andonovski’s youngest options at forward. After Swanson’s tendon snapped, the team immediately initiated the protocol for replacing an injured player, and had 18-year-old forward Alyssa Thompson join the team in St. Louis for the second friendly. (Thompson, a high school senior, was at practice for Angel City FC when she got the news, so she asked her mom to begin packing her bags and raced for the airport.) The day before that game, the coach praised the No. 1 pick of the 2023 draft for her ability to break down compact defenses, eliminate opponents on the dribble and run at defenses with confidence—“borderline arrogance,” he said, happily.

In other words, they honored Swanson the only way they could: They moved on.

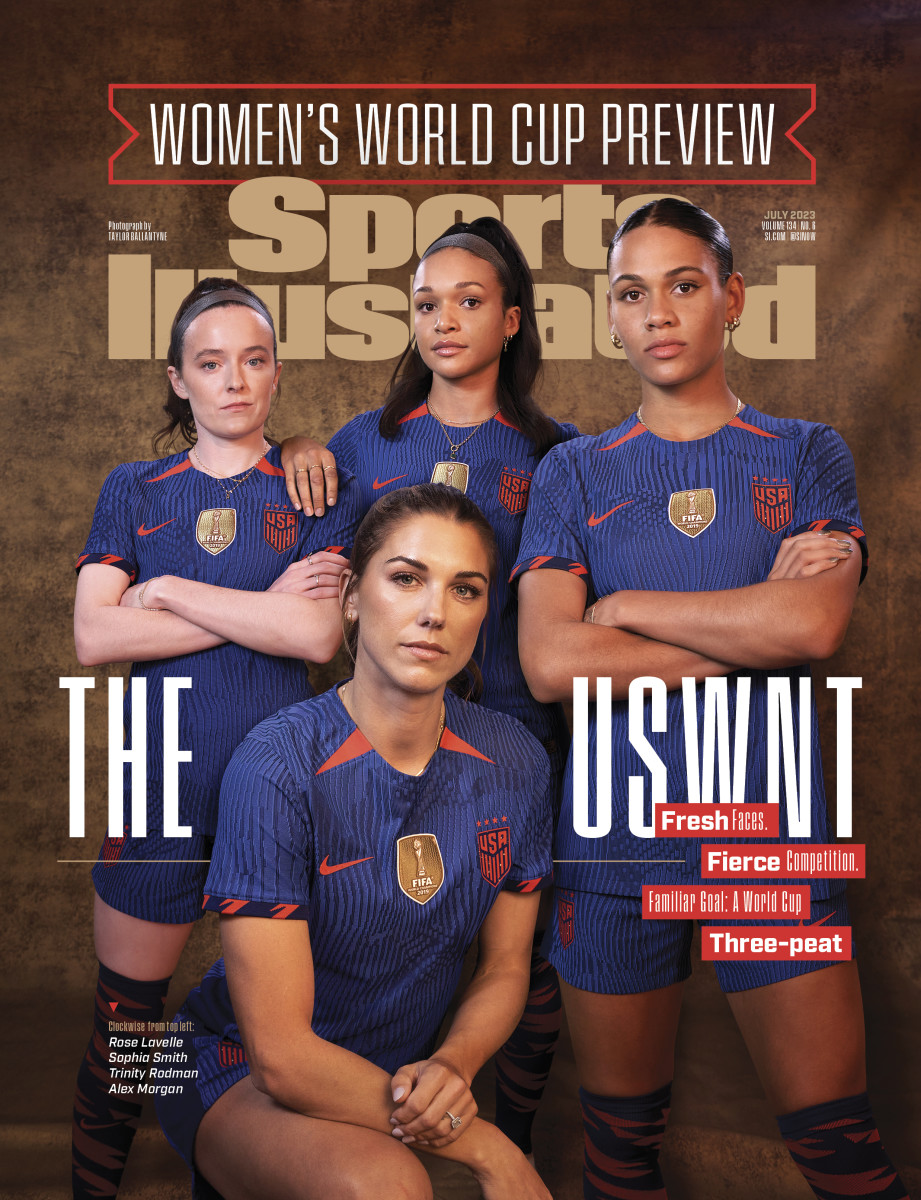

Back in Austin at the national team’s Sports Illustrated photo shoot, Girma darts around, waving her disposable camera. Smith and Lavelle giggle as Girma stands beside photographer Taylor Ballantyne, capturing her own shots. Finally 33-year-old forward Alex Morgan, enough of a veteran of this sort of thing that she slings around photo shoot jargon (“do you have an apple box?”), hushes them. “Game faces,” she insists. Her younger teammates comply.

Leadership is key with this group. “Becoming a leader is like falling in love,” Andonovski says. “It’s not something that you just say, ‘Tomorrow morning I’m going to be a leader on this team.’ It just doesn’t work like that. It’s a process.”

And the lines of who is a leader and who is a rising star are sometimes difficult to draw—“do I count as young?” asks 28-year-old Lavelle, who was the team’s breakout star at the 2019 World Cup. “I count you as young!” says Smith, the first player born in the 2000s to appear on the USWNT roster—but however you classify them, there are a lot of players on this team who watched Brandi Chastain’s 1999 World Cup celebration on YouTube rather than on TV. These players grew up with Morgan’s poster on their walls, then gaped when she invited them to dinner.

“She’s iconic,” gushes Girma, the top pick of the 2022 NWSL draft. “It’s crazy to get to play with her.” She adds, “We’re all just coming at it, like, open and trying to learn. And I think at the same time, bringing our own personalities and energy, and I think it’s a good energy that we all feed off of. And I think it’s a good balance of, like, you have the veterans who [bring] established leadership, and we’re kind of learning from them, but then also, like, they’ll joke around with us. I think it’s a good vibe.”

During the last World Cup, Andonovski says, “I don’t even think that the national team was set up for helping young players.” Andonovski—who coached for the Kansas City and Seattle NWSL teams from 2013 to ’19—was hired to replace Ellis less than four months after that tournament. The 46-year-old coach adds, “I don’t [mean], like, nobody cared. It wasn’t the structure of the environment itself; it was the structure of the team. It was, like, 90% veterans, whereas now it’s a little different.”

The idea is to raise their standards so they meet the program’s, so the coaching style allows for player development, and staffers take every opportunity to prepare young players logistically for what they will see in Australia and New Zealand. During the SheBelieves Cup, they took charter flights, as they will this summer; they held meetings at approximately the times they will this summer; and they scheduled games against teams that play different styles, as they will this summer.

The veterans teach the kids about everything from how to rest during grueling tournaments to how to choose endorsement deals to how to be creative on the pitch. And every so often, the kids can teach the veterans something, too. “There’s a good balance between the older players teaching us and also us pushing older players to continue to advance their own game,” says Davidson, who was the youngest player on the 2019 World Cup roster. “Sometimes some people might think like, Oh, you know, the older players are comfortable in their positions or you know, feel like they’ve learned everything that they can, but they’re always looking for, always hungry for, new challenges, and we bring that. We give it back to each other back and forth.”

Lavelle agrees—although declines, after some thought, to count herself among the kids. “I think they’re all game-changers,” she says. “You put them on, and they all have something that’s unstoppable and they can win it on their own. So when you put it all together, it’s like magic and it’s unstoppable. It’s incredible to have. It’s fun to play with.”

“The players on this team, they’re nasty competitors,” says Andonovski. “And nasty in a good way. … It’s passed on generation to generation, and I’m glad that now the next group is picking that up … because they’re gonna have to pass that on. And really, in some ways, I have a feeling that it’s almost like they have no choice.”

If you can’t take it in camp, he explains, you’ll never make it in high-level competition. In her last speech to the team before she retired, Lloyd summed it up neatly: “You’re either cut out for this or you’re not.”

The younger players believe they are cut out for it. They will have to prove it this summer—with a dynasty on the line.