The Best of Dan Jenkins

One of the best writers in the 64-year history of Sports Illustrated, Dan Jenkins died Thursday night at 90. Jenkins's career began with the Fort Worth Press and the Dallas Times Herald before joining Sports Illustrated, where he spent over 25 years primarily covering golf and football.

Here is a selection of Jenkins's best work for SI.

The Sweet Life of Swinging Joe

Issue Date: October 17, 1966

Stoop-shouldered and sinisterly handsome, he slouches against the wall of the saloon, a filter cigarette in his teeth, collar open, perfectly happy and self-assured, gazing through the uneven darkness to sort out the winners from the losers. As the girls come by wearing their miniskirts, net stockings, big false eyelashes, long pressed hair and soulless expressions, he grins approvingly and says, "Hey, hold it, man—foxes." It is Joe Willie Namath at play. Relaxing. Nighttiming. The boss mover studying the defensive tendencies of New York's off-duty secretaries, stewardesses, dancers, nurses, bunnies, actresses, shopgirls—all of the people who make life stimulating for a bachelor who can throw one of the best passes in pro football. He poses a question for us all: Would you rather be young, single, rich, famous, talented, energetic and happy—or President?

Read the rest of the story here.

The Glory Game at Goat Hills

Issue Date: August 16, 1965

Goat Hills is gone now. It was swallowed up almost four years ago by the bulldozers of progress, and in the end it was nice to learn that something could take a divot out of those hard fairways. But all of the regular players had left long before. We had grown up at last. Maybe it will be all right to talk about the place now, and about the people and the times we had. Maybe it will be therapeutic. At least it will help explain why I do not play golf so much anymore. I mean, I keep getting invited to Winged Head and Burning Foot and all those fancy clubs we sophisticated New Yorkers are supposed to frequent, places where, I hear, they have real flag sticks instead of broom handles. It sounds fine, but I usually beg off. I am, frankly, still over golfed from all those years at Goat Hills in Texas. You would be, too, if.... Well, let me tell you some of it. Not all. I will try to be truthful and not too sentimental. But where shall I begin? With Cecil? Yeah, I think so. He was sort of a symbol in those days, and...

We called him Cecil the Parachute, because he fell down a lot. He would attack the golf ball with a whining, leaping half-turn—more of a calisthenic than a swing, really—and occasionally, in his spectacular struggles for extra distance, he would soar right off the end of elevated tees.

Read the rest of the story here.

Nebraska Rides High

Issue Date: December 6, 1971

In essence, what won it for Nebraska was a pearl of a punt return in the game's first 3½ minutes. Everything else balances out, more or less, even the precious few mistakes—Oklahoma's three fumbles against Nebraska's one, plus a costly Nebraska offside, the only penalty in the game. There was an unending fury of offense from both teams that simply overwhelmed the defenses, maniacal though they were. But that is the way it is with modern college football. You can't take away every weapon. Both Nebraska and Oklahoma stopped the things they feared most, but in so doing they gave up practically everything else. From Oklahoma's record-cracking Wishbone T the Cornhuskers removed the wide pitch to the halfback, mainly Greg Pruitt, but in doing so they relinquished the keep, the fullback into the middle and most of all the pass. To stop Pruitt, the Cornhuskers were forced to cover Wide Receiver Jon Harrison man for man, which they did ineffectually, thus allowing Harrison to catch four passes in critical situations, two for touchdowns. From Nebraska's imposing I spread and I slot Oklahoma took away the passing game but gave up the power running attack. So the two teams swapped touchdowns evenly from scrimmage, four for four, and Oklahoma added a field goal. But always there lingered the one thing they had not traded, that sudden, shocking, punt return by Nebraska's Johnny Rodgers.

Read the rest of the story here.

A Braw Brawl for Tom and Jack

Issue Date: July 19, 1977

Go ahead and mark it as the end of an era in professional golf if you're absolutely sure that Jack Nicklaus has been yipped into the sunset years of his career by the steel and nerve and immense talent of Tom Watson.

You could argue that way now, in these hours after Tom Watson has become the new king of the sport in a kingly land; when Watson has already become the Player of the Year, not to mention the future; when he has done it in the most memorable way in the annals of golf; and when he has done it for the second time in this season to the greatest player who ever wore a slipover shirt—Jack Nicklaus.

You could also say it very simply with numbers. In the last two rounds of last week's British Open, Tom Watson shot 65 and 65 to beat Nicklaus by one stroke. Oh, by the way, they were playing together. Oh, yes, and another thing: Watson's 72-hole total was 268, which was a new record by only eight shots. And, incidentally, the victory gave Watson his second major title of the year (and the third of his fresh and exciting career); he had taken the Masters, of course, standing up to Nicklaus in a slightly different type of pressurized situation. And, let's see, the British Open gave the handsome young Watson his sixth win of the year and some $300,000 in tour earnings.

Read the rest of the story here.

The Disciples of St. Darrell on a Wild Weekend

Issue Date: November 11, 1963

On Friday morning, October 11, a bright, warm Texas day, Elbert Joseph Coffman woke up with a squirrel in his stomach. In his good life as a football fan there had never been a weekend quite like this one. In the next 55 hours he was going to see three college games and one pro game, and the excitement of it, the bigness of the games, made him nervous. Nervous but delighted. Football to Joe Coffman, and thousands of other Texans, is as essential as air conditioning. It is what a Texan grows up with, feeds on, worships, follows, plays and, very often, dies with. Joe Coffman, 32, married, father of two boys, businessman, University of Texas graduate, football enthusiast, was either going to live a lot this weekend or die a little.

The first game—SMU against Navy—would be played that evening in the Cotton Bowl in Dallas, just 35 miles away from Joe Coffman's home in Fort Worth. The next day he would go back to the same stadium to see the biggest one of them all, Oklahoma, ranked first in the country, against Texas, ranked second. He would drive to Waco (90 miles south) Saturday night to watch Baylor against Arkansas. And on Sunday he would return to the Cotton Bowl to see the NFL's Dallas Cowboys play the Detroit Lions.

Read the rest of the story here.

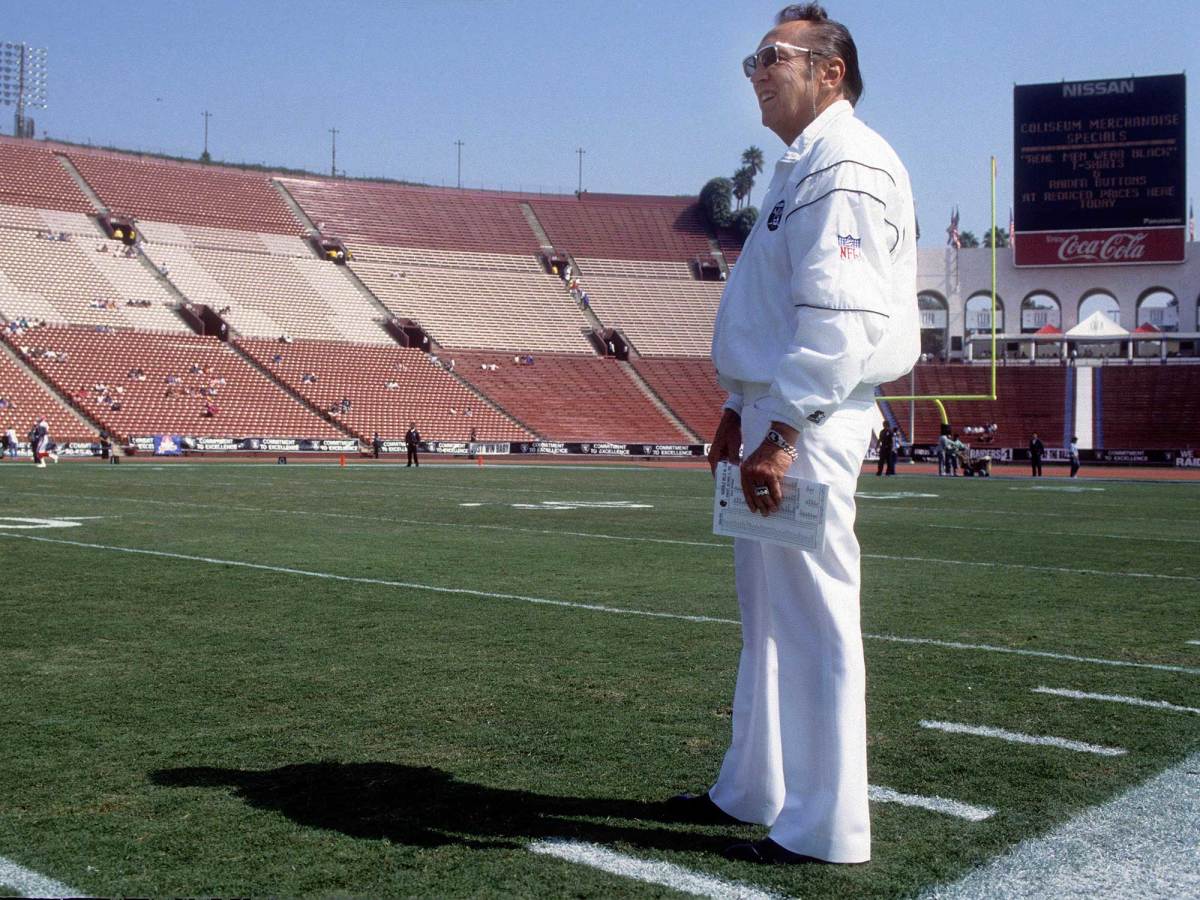

What the Raiders Have Is Genius

Issue Date: December 2, 1974

In fear of drowning, the writer tests the carpet in the office of Al Davis to see if it has been watered down the way they say the field is for all home games of the Oakland Raiders. Al Davis laughs. Being a genius, a winner, rich and powerful, he can afford to laugh. The writer explains that he has been sentenced to pro football this year and he has come to Oakland on a vacation to get away from it all. He likes what they're doing with the marsh areas.

"Hey, can I say something?" says Al Davis. "I don't know what I'm doing here today. You know what I...? If it was anybody else but a guy I haven't seen in a while...I could be...See, John Madden's the coach...."

The writer didn't catch the last name. John who?

Read the rest of the story here.

A High Kind of Low Life

Issue Date: July 6, 1964

In professional tournament golf the clubhouse veranda can be a noteworthy blend of rumble seat, wax museum, promenade deck, theater wings and courthouse steps. As the tour moves from one Crystal Rancho Happy Avocado Creek Country Club to another, the verandas undergo some severe botanical changes—for example, palm trees become pines and vice versa—but the human plant life remains practically changeless. Except for the occasional intrusion of a spectator, fully equipped with binoculars, periscope, chair seat, transistor and hot dog, and the almost invariable presence of at least one young girl in Capri pants beneath a large straw bonnet, the regular veranda standers comprise a remarkably homogeneous and identifiable part of golf. They are the in-group, style-casual, up-scale, hanging-in, cooling-it businessmen of the game. And as they spread across the lawn, gazing toward the nearest leader board while a tournament progresses, they are not unlike a cluster of military commanders watching the glow of shellfire from a distant valley.

To almost anyone who knows the difference between a Black Dot and a Titleist, the faces of these fringe personalities look as familiar as casual water, but only the true insider will be able to identify them by name, to know that the stocky, pink-faced man in the dark suit with his hands folded behind him, the one telling Sam Snead stories, is Fred Corcoran, Snead's lifelong agent; to know that the tall, blond fellow talking to Winnie Palmer is Mark McCormack, the Cleveland lawyer and agent for golf's Big Three; to know J. Edwin Carter of the World Series of Golf; Bob Rickey, the Brunswick-MacGregor vice-president; Ernie Sabayrac, the golf equipment distributor; Bob Drum, the freelance promoter; Jim Gaquin, the PGA tournament manager. And it takes an insider, too, to know the name that goes with the most familiar face of them all, the one belonging to a man called Bubble Head, a man who is always there and is never doing anything.

Read the rest of the story here.

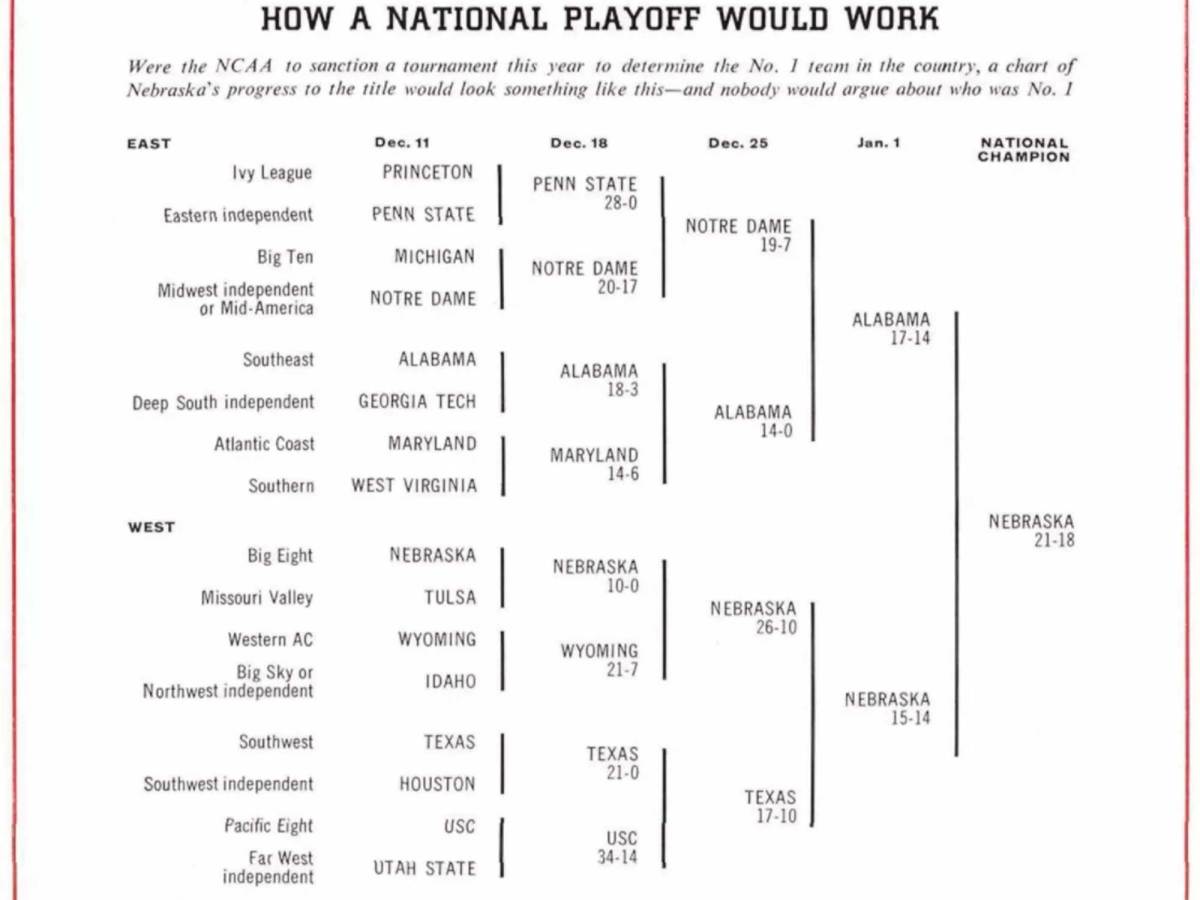

...And Nebraska Has the Guns

Issue Date: September 20, 1965

There is of course a way for the NCAA to satisfy the public: play to a national title. The chart on the preceding page, based on this magazine's scouting reports, illustrates what could happen if there were a playoff. The scores are intended to reflect this year's strengths—and Nebraska is the champion, with its closest call against Texas in the semifinals. The country is divided East and West as accurately as possible for balance, all major areas are included and the first-round games determine regional superiority. For playing sites, it seems needless to point out that there are eight major bowl sponsors who would be pleased to continue their promotions.

Although the NCAA decides national champions in most other sports—for instance, fencing—its main argument against a football playoff centers vaguely around overemphasis. But as long as the administrators fire coaches, sell tickets, recruit athletes, play postseason games and peddle their product to television they are kidding no one.