That Time Obama Pardoned a Guy Who Stole Charlie Sheen's Honus Wagner Card

On Dec. 19, 2016—weeks before he left the White House to Donald Trump—Barack Obama, like so many U.S. presidents exiting office, issued a list of pardons. All told, he erased or commuted the sentences of 231 citizens, mainly nonviolent offenders. A few were still incarcerated for acts committed years, even decades ago, but most had already paid their debt to society and simply wanted a fresh start with a clean record.

There was Dawn Mascari, an FBI dispatcher who in 1998 used her inside information to tip off a bookmaker to the fact that he was being investigated. And Ralph Hoekstra, who in 2005 pleaded guilty to illegally buying endangered dwarf Indian star tortoises online. And Sala Udin, a black activist charged in 1970 with unlawfully transporting firearms and possession of untaxpaid distilled spirits in Kentucky. And meth dealers. Lots of meth dealers.

Rebuffed by Obama were the pleas on behalf of the late heavyweight champion boxer Jack Johnson, who in 1912 had traveled with a white woman and, under the Mann Act, was convicted of “transporting” her across state lines for “immoral purposes.” (President Trump pardoned Johnson in 2018; two years later he pardoned former 49ers owner Edward DeBartolo Jr.) But Obama did address one case with sports ties, clearing the record of a New Jersey man who two decades earlier schemed with others to steal one of the most valuable baseball cards from the world’s most high-profile sports bar.

* * *

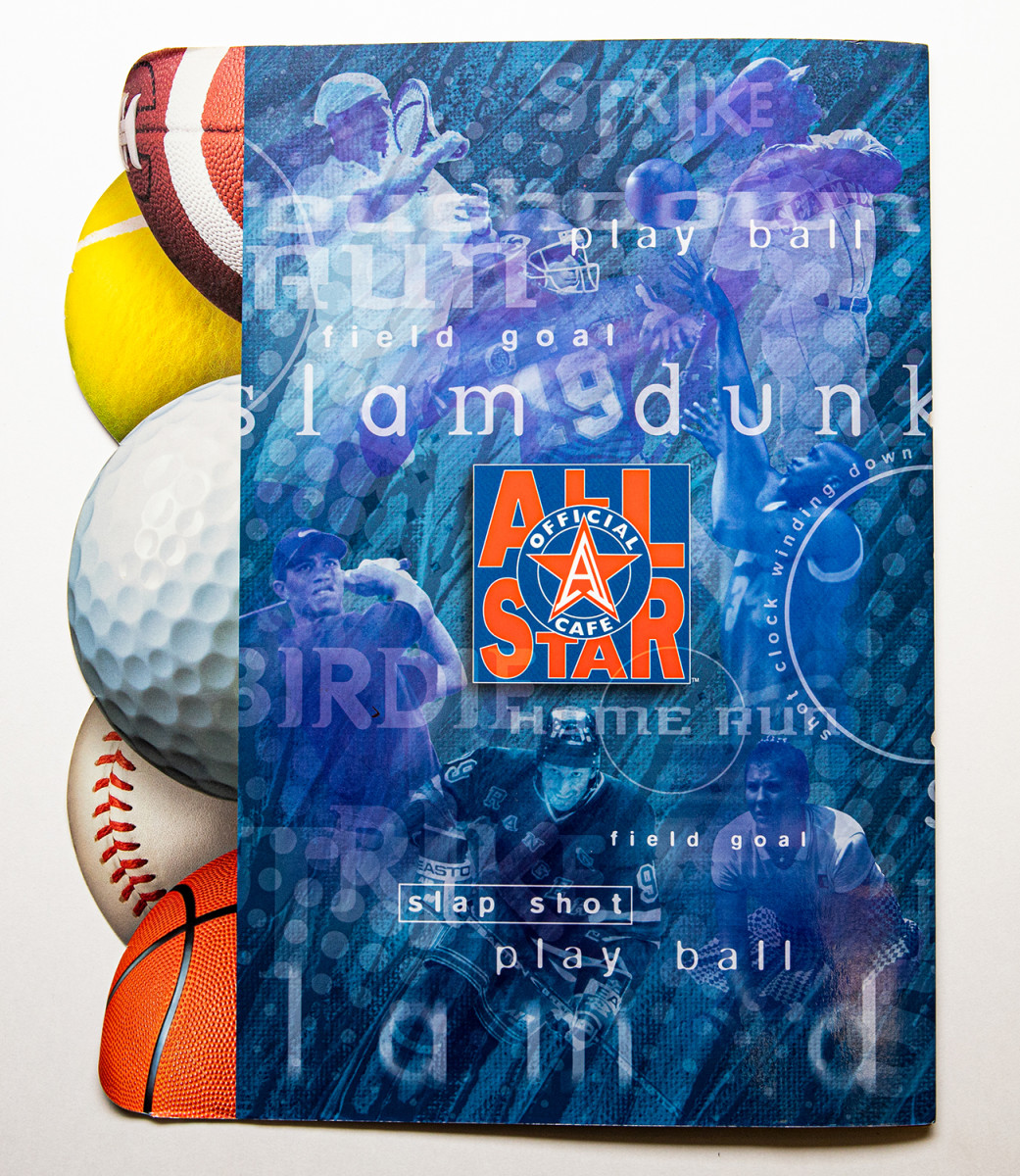

If you’re looking for a snapshot of American culture before the turn of the last century—when traffic was starting to thicken at the four-way intersection of sports, celebrity, media and commerce—you can’t do much better than the scene at 1540 Broadway in New York City on Dec. 18, 1995. The grand opening that night of the first Official All‑Star Café reflected the latest in a trend of gaudy, zeitgeist-capturing theme restaurants. In ’92 there had been six such chains in the U.S., doing $300 million in total revenue. Within six years there would be 30, doing $2 billion.

At the center of all this was Robert Earl, a British restaurateur (in the loosest sense) who started his crusade against fine dining in the 1970s with a medieval-theater-themed eatery, Beefeater; then developed the music-centric Hard Rock Cafe; then partnered with the likes of actors Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis and Demi Moore to launch Planet Hollywood for hungry movie fans. The next iteration of his meal ticket focused on sports.

Fronted by Andre Agassi, Wayne Gretzky, Ken Griffey Jr., Joe Montana, Shaquille O’Neal, Monica Seles and PGA Rookie of the Year Tiger Woods, among others, the first All-Star Café was a 34,000-square-foot, three-story monstrosity with seating for 650 at the midcourt circle of Times Square. Earl grandly described the venue as “an arena meets a stadium,” and the opening was a festival of excess. Paparazzi and news cameras flanked red carpets. Limousines dotted the block. A jockocracy including John McEnroe, Roger Clemens, Doc Gooden, Sugar Ray Leonard, Mike Tyson and Evander -Holyfield—the last two would share an intimate bite inside the ring 18 months later—turned out, along with celebs such as Charlie Sheen, Stevie Wonder, Whoopi Goldberg, Mayor Rudy Guiliani and a Manhattan man-about-town who seldom missed this kind of photo op, real-estate developer Donald J. Trump. Mid-party, Blues Traveler front man John Popper grabbed a harmonica and belted out a few songs, though according to the Daily News, “the highlight of the evening had to be our overhearing Cindy Crawford giving marital advice to Brooke Shields.”

“Take your pick of sports metaphors,” Entertainment Tonight’s Pat O’Brien cooed from the scene. “You can call it a slam dunk. . . . Game, set and match. . . . He shoots, he scores! . . . The place looks like a real winner!”

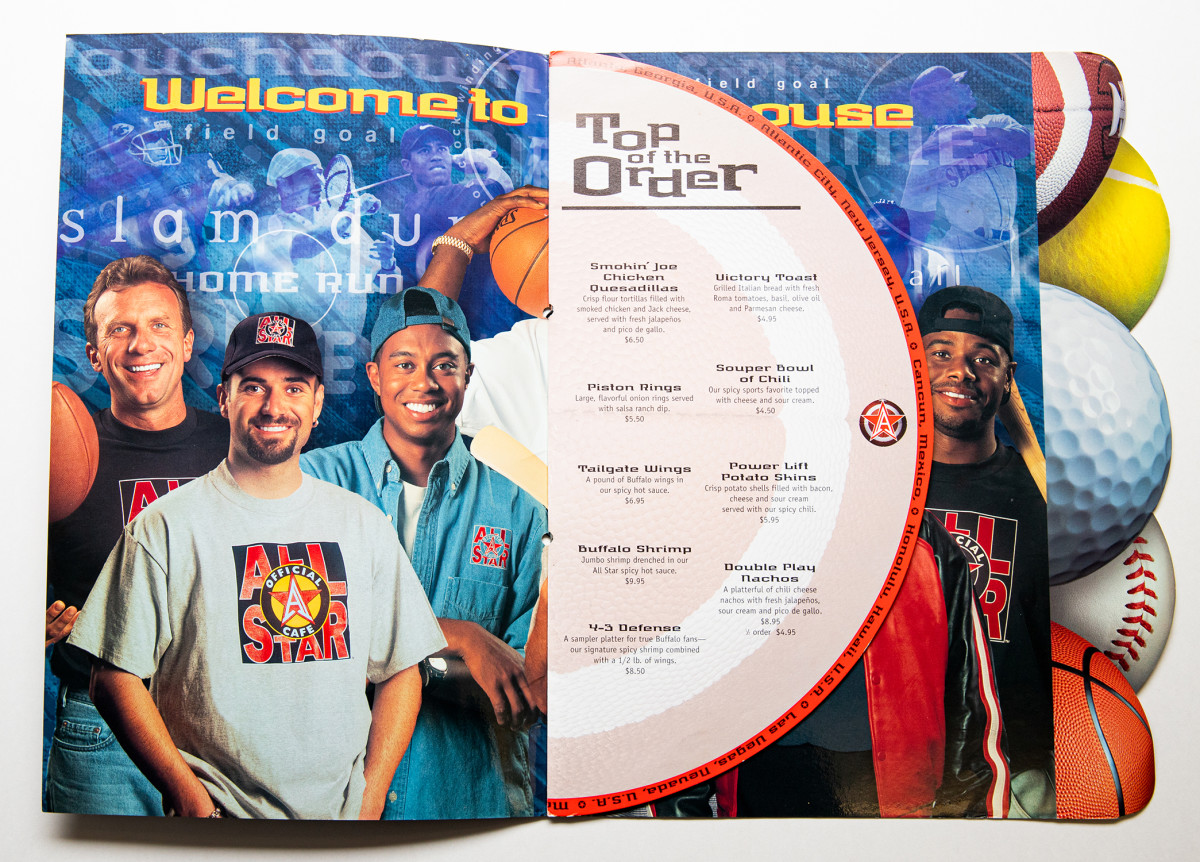

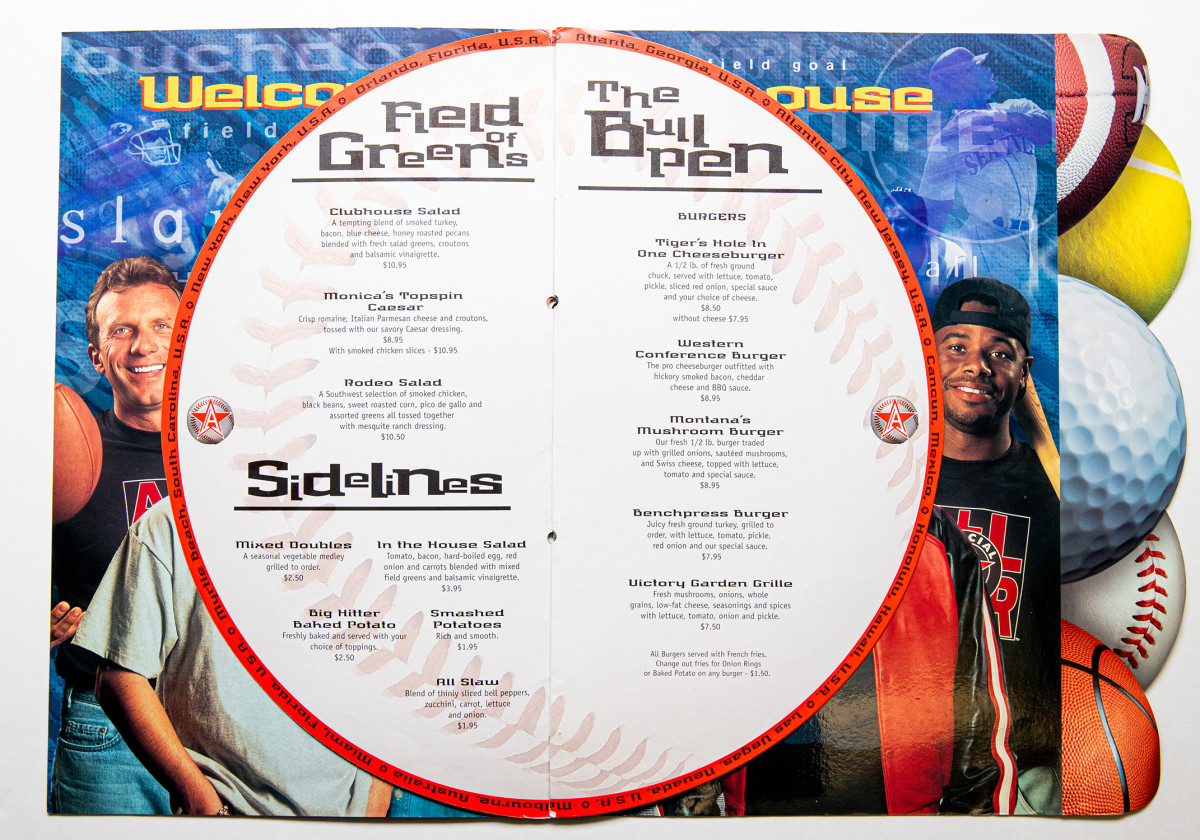

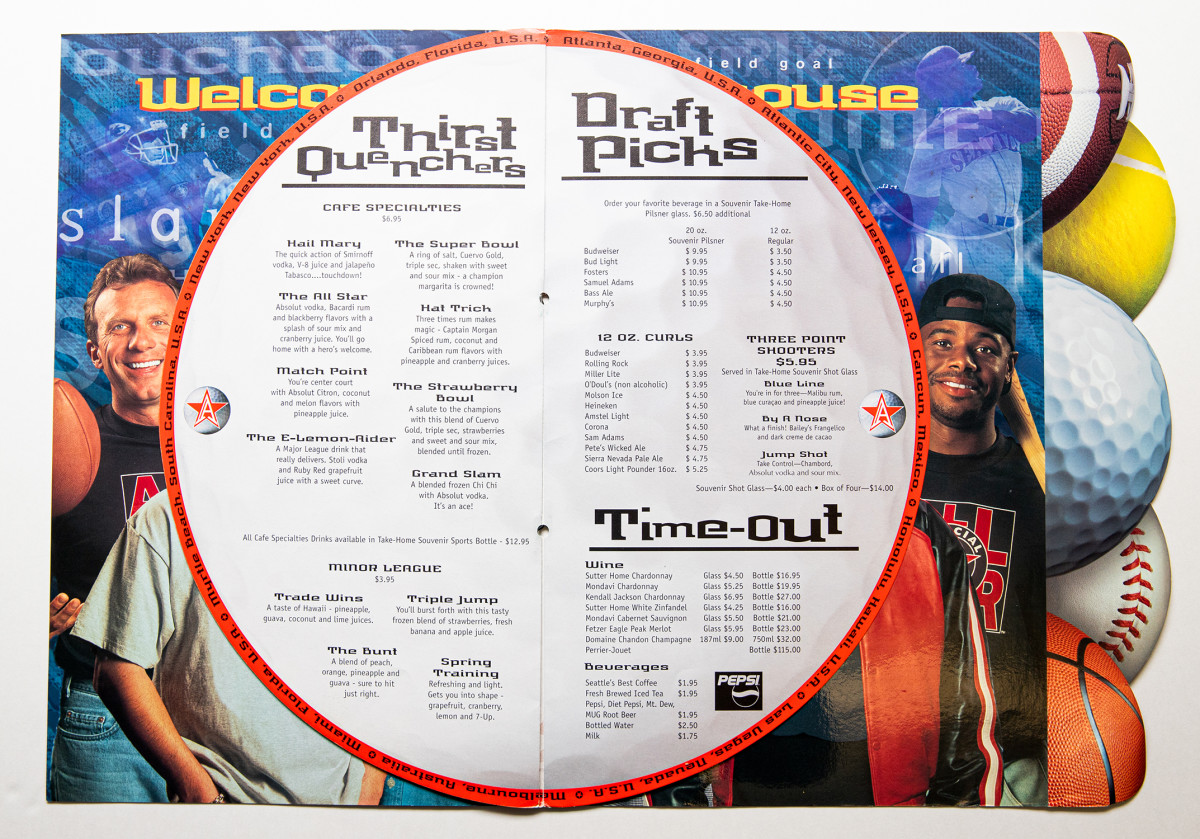

The food was a different matter. Here was the rare restaurant that regarded meals as an afterthought, if not an outright inconvenience. Offering “stadium cuisine” at commensurate markups, the menu included burgers served 51 ways, hot dogs from Yankee Stadium and four other ballparks, and the usual array of artery-clogging concession-stand fare. (There was also, perplexingly, a matzo ball soup.)

The café’s appeal rested almost solely in its genuflection to sports. Patrons sat in booths shaped like baseball mitts while a miniature blimp circled overhead, sometimes obscuring the games airing across 70 TVs. Memorabilia lined every wall—signed jerseys and photos, programs and pennants, game-used bats and balls—and much of it was valuable, often provided by the athlete-backers themselves. Half-saloon and half-salon, the New York City location featured both Babe Ruth’s camel-hair coat and the backboard stanchion Shaq had once famously collapsed with his heft. Agassi, then still known for an extravagant mane of hair, donated a clipped ponytail for display.

Then there were the baseball cards, most of them belonging to Sheen, the bad-boy actor whose lifelong affinity for America’s pastime only intensified after he starred in a pair of Major League movies. As an investor in Earl’s sister chain Planet Hollywood, he loaned dozens of his cherished collectibles to the All-Star Café, where they were displayed under plexiglass in what was referred to as the “Sheen Room,” near the main bar.

The actor’s pièce de résistance: a 1910 Honus Wagner card, known across the memorabilia industry as T206 (referring to the catalog number of the set in which it appeared). An inaugural inductee into Cooperstown, the Pirates shortstop was one of the first athletes to exert control over his image. Soon after the American Tobacco Company issued Wagner’s debut card, he demanded it be taken out of circulation because he didn’t want his name affiliated with cigarettes. (An alternate history has Wagner wanting to be paid for the commercial use of his likeness.)

In 1996, when there were only a few dozen T206s known to be in circulation, one sold at auction for $640,500. Which is why it came to be the focus of a few All-Star employees’ attentions.

* * *

It was a harebrained idea, hatched, as harebrained ideas so often are, over a few drinks. While law enforcement officials would later call the theft of Sheen’s T206 a “scheme,” that characterization suggests way too much sophistication and planning.

After his shifts at the All-Star Café, Thomas Gartland, the restaurant’s executive chef beginning in 1997, would often repair to the third-floor bar, or to the nearby Bull Moose Saloon, to unwind with colleagues and recount stories from the day’s work.

There was the time Shaq held his raucous 25th birthday party at the All-Star Café. “I bet we went though 250,000 shrimp that night,” says Gartland. Or the day Thurman Thomas came in and Gartland says he teased the Bills running back about famously misplacing his helmet at Super Bowl XXVI. “You didn’t lose your helmet,” Gartland says he joked. “You were just scared s‑‑‑less!” Thomas, Gartland says, punched him. (Thomas denies this ever happened.)

Anna Kournikova, then in her teenage tennis prime, held a press conference at the restaurant, which made for plenty of chatter. Actress Demi Moore came in and inquired about hosting a kids’ birthday party. Tom Arnold was a regular at the bar, smoking a cigar with his drink, and employees once watched Liv Tyler sit by herself, declining offer after offer to keep her company, like a coach cutting all the hopefuls who show up for open tryouts. “It was in our contracts: We couldn’t [socialize] with the celebrities or ask for autographs,” says Gartland. “But after work we’d all get together and compare stories.”

One chilly March night in 1998, as Gartland drained beers with the All-Star Café’s maintenance manager, Greg Corden, talk turned to the coveted 1 7/16-by-2 5/8-inch piece of cardboard that stared at them temptingly every day. Not only were there no cameras or alarms at the All-Star Café, but the display case for the T206 wasn’t even locked. What if they stole the Wagner card and sold it? “Jealousy. Greed,” Gartland says today, weighing his motivations to pilfer from all these displays of wealth. “It’s like we wanted to live bigger lives.”

Into this scheming stepped Gartland’s 20-year-old nephew, Benny Ramos, who would come by the café to watch sports, hang out with his cool uncle and get a contact high from all the celebrity. A prelaw major and defensive back at St. Peters, across the Hudson in Jersey City, Ramos had no criminal past and no real interest in baseball cards—but when he overheard the conversation about lifting the T206, he was dumbfounded. He’d seen enough heist movies to know these guys were amateurs. “You can’t just take the card,” he said. “You need to replace it with a fake, so no one knows it’s missing!”

With that, the newly expanded crew hatched a plan. Ramos found a depiction of the Wagner card in a biographical book and, at his uncle’s behest, he says, made a color photocopy, which he mounted on cardboard. Corden allegedly removed the rivets from Sheen’s display case and replaced the original card with the counterfeit. The conspirators then hid the T206 behind a ceiling panel in the restaurant’s stock room. In the ensuing weeks, thousands of customers walked by the case. None noticed anything amiss.

Emboldened, Gartland removed the original card from the ceiling and took it home to Bloomfield, N.J. (Gartland spoke to SI for this story but was reluctant to discuss certain specifics.) He arranged to sell the T206 and gave it to Ramos to deliver.

“I should have known better,” says Ramos. “I knew it was wrong. But it was a family member and, whatever he tells you to do. . . . I felt used.”

* * *

Alan Rosen had reached such prominence as a baseball-card dealer by the time Ramos knocked nervously on his door in Montvale, N.J., that he had been profiled in Sports Illustrated under the headline mr. mint. When Rosen asked about the provenance of the treasured card, Ramos responded unconvincingly: “I found it in my grandfather’s closet.”

Rosen would have known that a T206 Honus Wagner had sold for $222,500 just a few months earlier, at a Christie’s auction in Manhattan. That he was offering just $18,000—far below market value, even given that Sheen’s T206 wasn’t in mint -condition—suggests Rosen wasn’t buying Ramos’s story. (Rosen died of leukemia in 2017.) But Ramos accepted, and the conspirators divvied up the cash. According to court documents, Ramos kept $2,000; Gartland and Corden each took $8,000.

Then, predictably, the gang got greedy. After business hours on April 21, the All-Star Café’s assistant chef, Michael Hess, a new coconspirator, allegedly broke into another display case and removed more of Sheen’s loot: a 1910 T206 of Phillies outfielder Sherry Magee worth $25,000 and an uncut sheet of 25 Goudey Gum Company cards from 1934 that included a rare Nap Lajoie (a Hall of Fame Indians infielder), which alone could fetch $35,000.

Ocean’s 11 this wasn’t. Hess cracked the plexiglass glass in the process of extracting the cards, which he scrambled to hide in a desk drawer at the restaurant. When employees arrived the next morning, they immediately saw the broken case and called the police. And with the NYPD on the way, the panicked thieves absconded, their spoils tucked into a backpack, to Gartland’s home, where—insert audible collector’s gasp—they cut up the sheet.

Again, the off-loading proved a serious disappointment. Ramos reengaged Mr. Mint, telling him the cards had come from an uncle’s collection, and got $3,500 for the Magee. Two of the other cards had been ruined in dissecting the sheet; the rest were sold at a cut rate.

The take for the Lajoie and a pair of other salvageable cards: just $11,000.

* * *

When Patrick Gildea, a young agent with the New York City office of the FBI’s major theft squad, learned of the case and offered his help to the NYPD, he says he was told, “Be ready for a fight.” Such were the turf wars between law enforcement agencies in those days. To break the ice, Gildea showed up to the Midtown North Precinct wearing boxing gloves hanging around his neck.

Gildea contacted the head librarian at the Baseball Hall of Fame and collected the names of the top 25 memorabilia dealers on the East Coast. He then sent a form letter to each one, asking if they’d purchased any suspicious cards lately. “That was on a Wednesday,” Gildea recalls. “By Monday morning I got a call from the lawyer for Mr. Mint. He says, ‘I think I got what you’re looking for.’ ”

Yes, Rosen explained, he’d recently procured such cards. To save his reputation and avoid charges, he offered to return them and help identify the seller.

In looking for the thieves, Gildea came across the name of a Marine who’d gone AWOL and was now working in the All-Star Café kitchen. “That guy,” Gildea explains, “was collateral damage.” But it pointed the FBI in the right direction, toward the idea of an inside job. “Turn over a few stones, and yeah, there were quite a few interesting characters working in that restaurant.”

By the end of the summer of 1998—with the restaurant’s TVs tuned to the -Mark McGwire–Sammy Sosa home run chase—the case of the All-Star Café robberies was cracked. Gartland was arrested and became a cooperating witness for the government. “Once we started flipping guys,” says Gildea, who retired in 2016, “it all came together.”

Among those who cooperated was Ramos, who says that during his interview about the missing sheet of cards he casually mentioned the stolen Wagner. Noting the investigators’ perplexed looks, he asked, “You guys didn’t know that, did you?”

Sheen, upon learning of the thefts, removed his collection from the All-Star Cafés in New York and in Las Vegas, where a new franchise had opened. He issued a statement praising the FBI and the NYPD and added, “I am deeply saddened that such precious artifacts have been mutilated by amateurs in the pursuit of greed.”

A year later, in April 1999, the charges came down. Gartland, Ramos, Corden and Hess were each charged in federal court with selling stolen property and conspiring to take it across state lines, felonies that can carry sentences of up to five years in jail and $250,000 in fines. (Had the defendants not taken the cards to New Jersey, theirs would likely have not been a federal case.)

All of which floored Ramos, who remembers thinking it was a mistake when he was first apprehended. He says he’d considered it all more of a prank than a theft. The handcuffs lifted any fog of confusion. “I was prelaw; I wanted to be a defense attorney,” he says. “Suddenly I became a defendant.”

As the first member of his family to go to college, Ramos was determined to stay in school. On the advice of his lawyer, he pleaded guilty on the condition that he would serve no jail time. The hardest part of the ordeal may have been telling his mother. “You’re a grown man,” she told him. “You make your own decisions. It’s your responsibility to get out of trouble.”

The three older men, like Ramos, pleaded guilty. Corden, who had removed the Wagner card, was sentenced to four months in prison; Gartland, Hess and Ramos were put on probation. And Sheen, in the end, went to New York City to pose with Gildea at a small recovery ceremony.

As for the two cards that had been destroyed, and the devaluation of the other Goudey and Magee cards as a result of their theft and cutting, Sheen was owed restitution, and in an order dated Dec. 27, 2000, the U.S. Department of Justice wrote:

Dear Mr. Sheen

As you may be aware, the United States Attorney’s Office is responsible for the collection of unpaid restitution. Therefore, this Office will make every effort to ensure that the defendant(s) makes full restitution to you.

And so it was that Gartland, Ramos and Hess (who would die in 2007) were each ordered to repay Sheen: $50,000 from Gartland, and $5,000 each from Ramos and Hess. Records show that for the next three years the men scraped together installments—payments ranging from $90 to $2,500 at a time—and sent them off to one of the most famous actors in the world.

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

Photograph by Abby Nicolas

* * *

By the end of the first year of the new millennium, the All-Star Café had bigger problems than a few missing pieces of cardboard. In keeping with the bust-and-boom rhythm of sports, Earl’s chain fell on hard times following a smashing debut season. The Times Square location was the first of 10 franchises across the world—a pace of expansion that proved entirely too rapid. Sources tell SI that none of the restaurants were profitable. And each, it seemed, came with a personalized tale of woe.

In Times Square an employee allegedly stole a $70,000 bottle of wine from a party for a New York real estate magnate. More damaging: As Manhattan rents went, inexorably, up, revenues went down.

A waterfront Miami franchise with 260 seats opened in July 1997, but the party had a somber tone. Two weeks earlier designer Gianni Versace had been murdered at his South Beach residence, a block away.

Three and a half hours north, in Orlando, another franchise suffered lousy foot traffic while a brutal Sentinel review noted that customers would “be better off with a hot dog from a stadium vendor.”

Beyond the bad acts, bad luck and bad reviews, the theme-restaurant fad was falling out of favor. Patrons, most of them tourists, were happy to experience the novelty. But joints like Planet Hollywood were not cultivating repeat customers, the cornerstone of any successful eating establishment. Three blocks away from the Manhattan franchise, David Copperfield’s Magic -Underground—with its ambitions of marrying “magic, merchandise and good food”—was $34 million into construction in June 1998 when the owners pulled a disappearing act. It never opened. In L.A. the Steven Spielberg–backed Dive!, where diners scarfed sub sandwiches in mock submarines, shuttered. So did an eatery built around the Billboard charts. Marvel Mania, at Universal Studios in L.A., barely got its comic book heroes past the press release stage. David Liederman opened the TV-themed Television City in ’97, beneath NBC’s Rockefeller Center headquarters in New York City; when he converted it two years later into a conventional restaurant, Chez Louis, he declared to The New York Times, “I am leading the de‑theming pack. I think there is going to be a massive exodus out of this business.”

And there was. In early 1999 the All-Star Café failed to come up with $12.5 million due to lenders and then failed to make another $15 million interest payment. By October, All-Star’s parent company, Planet Hollywood, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. A company that had gone public in ’96 with a share price of $18 was now trading at less than 75 cents. As part of the reorg, nine of the 10 All-Star Cafés soon after closed. (The Orlando outpost, folded into Disney’s Wide World of Sports, survived another eight years.)

In December 2000, Agassi, Montana, Seles and Woods petitioned a U.S. court in Delaware, seeking an order to return their memorabilia and remove their names from the menus and merchandise of all remaining All-Star Cafés. (They also asked for unspecified damages after being largely excluded in the bankruptcy reorganization plan.)

Ultimately the company complied, returning tennis rackets and basketball shoes and helmets. Agassi even got his ponytail back. But that was the extent of the giving. The athletes, according to their lawsuit, had signed contracts promising compensation, including stock shares, for their promotional work with the restaurant, but that deal, according to multiple sources, was never honored. The athletes were never paid. (Earl did not return calls seeking comment.)

* * *

The All-Star Café became a cultural artifact from a bygone era, on the order of Angry Birds or “Gangnam Style.” For the athletes who aligned themselves with the restaurant, their careers continued: In the year after bankruptcy was declared, Woods and Agassi won golf and tennis majors. So, too, did Earl continue in the restaurant sector. Today the -Orlando-based Earl Enterprises includes Italian fare like Bertucci’s and Buca di Beppo, as well as fast food like Chicken Guy! (a Guy Fieri joint found in football stadiums and at Disney World) and Earl of Sandwich (in which Roger Clemens and Nolan Ryan are investors). And, yes, six remaining Planet Hollywood locations. Today the space at 1540 Broadway is home to one of them, an outlier in a landscape bereft of theme restaurants.

For Ramos, though, the past was always present. He had to notify authorities anytime he left New Jersey. He lost the right to vote. Fearing the stigma of a felony record, he abandoned his prelaw major and then his pursuit of a career in finance. “I know it’s something you hear all the time,” he says, “but one mistake can totally derail your plans.”

In his mid-30s, a decade removed from the Honus Wagner caper, he was still toiling away in the food-and-beverage industry, only now he was ineligible for a variety of bartending and serving licenses that would have unlocked better-paying jobs. Then in 2015, through a mutual acquaintance, he met Vallerie Magory, a tax lawyer who asked him delicately, “Why is someone so bright and so personable stuck in such modest employment?” Ramos replied, sheepishly, by telling the story of the card heist and its profound consequences.

Defense work isn’t Magory’s area of practice, but she is a self-described “compliance nut, a dotting i’s and crossing t’s person.” And she did have experience working with the government. She asked Ramos whether he’d had any trouble with the law since the incident. After what happened, I don’t even speed. Was he willing to submit to an FBI investigation? I have nothing to hide. In that case, Magory suggested, they should file for a federal presidential pardon. “It was a long shot,” Ramos says he figured, rightly, “but why not?”

Magory guided him through pages of paperwork and through FBI interviews, then found the name of Ramos’s pardon attorney and checked in persistently. When Sheen himself landed in legal trouble for assaulting his wife and was investigated for allegedly stalking an ex, Magory saw it through the prism of Ramos’s petition: “I’m like, Oh, good, he’s become less credible and less important.” (Sheen pleaded guilty in his domestic abuse case and was sentenced to rehab, probation and anger management; no charges came of the stalking investigation.)

Through it all, Ramos went about rebuilding his life, saving up for a home in Queens. He married and became a father. Then he got a call from Magory that would change his life. Obama, while vacationing in Hawaii during his last full month as President, had issued a list of pardons. And Ramos’s was one of them.

The announcement came freighted with mystery, much of it still unsolved. Why, Ramos wonders, was he chosen from among thousands of applicants? (Neil Eggleston, White House counsel at the time: “While each clemency recipient’s story is unique, the common thread of rehabilitation underlies all of them. For the pardon recipient, it is the story of an individual who has led a productive and law-abiding postconviction life.”) And what of Sheen? Given that victims usually offer an impact statement, did he approve this pardon, or even lobby on Ramos’s behalf? (The actor did not respond to messages from SI seeking comment for this story.)

In some ways the pardon, ultimately, didn’t change much for Ramos. He had completed his parole long ago and for years has worked the same job, managing an upscale Mexican restaurant in lower Manhattan. In other ways the pardon has changed everything. It acted as a solvent, removing a blemish not just from his record but also from his self-image. Now 41, he has the thick build of a former athlete and an easy smile, but his voice catches when he says he feels free. He had been dreading telling his daughter that Daddy isn’t allowed to vote. “Now,” he says, “I don’t have to do that.”

Ramos has access to a new, expanded universe of opportunity. “All those jobs with benefits and stability,” he says, “I can apply because I’m pardoned.” He plans to stay in the food industry, where he’s built a reputation over the last 15-odd years, and the irony is not lost on him that he has anchored his working life in the very sector where his first career plans were derailed.

“I can tell you this,” he says as a grin forms inside the frame of his goatee. “If I ever do open my own place, it’s not going to have any memorabilia.”

This story appears in the March 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here