Despite the Blackout, Sports Are Still Playing a Critical Role in the Coronavirus Pandemic

It’s still early days in this crisis. And in sports, as in life at large, the coronavirus is still managing to outpace the news cycle, the media equivalent of the sub-two-hour marathon. We can scarcely contemplate an NCAA tournament played before no fans, no cheerleaders, and no crying piccolo players… When all of March Madness gets canceled. We are pondering how to shift our viewing habits to outdoor sports like golf, baseball, and NASCAR… only to see those join hoops and hockey on the sidelines.

But one of the more telling episodes so far—again, early days—came on March 9 when Jazz center Rudy Gobert stood before a podium. He was there because of an early precaution against the spread of a potentially deadly virus, so the NBA prohibited reporters from locker room access. Having just completed his interview session by answering a question about COVID-19, Gobert stood, smiled, and then pawed the many recording devices before him. It was done playfully, not maliciously, but still with the intent of sending a message. A few weeks removed from playing in the NBA All-Star Game, Gobert wasn’t about to get dunked on by a microscopic virus.

You know, of course, what happened next. On March 11, Gobert took ill. Moments before the Jazz were to play the Oklahoma City Thunder, word came that Gobert had tested positive for COVID-19. The game was immediately canceled, as the Chesapeake Energy Arena PA announced to the fans, before adding, “You’re all safe.” Within the hour, the NBA had suspended its entire season.

As for Gobert, he was, to his credit, equally embarrassed and apologetic. Generous, too: Three days after the NBA season vanished, he announced he would donate $500,000 to support both an employee relief fund at Vivint Smart Home Arena and COVID-19 related social services relief in Utah, Oklahoma City and his native country of France.

In a way, Gobert became the face of this reality: sports were not going to play their typical collective role in this crisis. In past catastrophes, sports has been there reliably to distract and unite and remind us of the power of the shared experience. In times of trouble, sports have been the magnet that de-polarizes us. It’s Big Papi reinforcing the message of Boston Strong. It’s Derek Jeter—after the President George W. Bush throws a perfect-strike first pitch—at Yankee Stadium after 9/11. It’s Drew Brees piloting the New Orleans Saints during Hurricane Katrina clean-up.

This time it’s different. It’s not just that sports events and games aren’t there as diversion and comfort and a show of an untattered social fabric. It’s that sporting events would manifestly make this crisis worse. At a time when we are being told to avoid gatherings of more than 50 people, you could scarcely conceive of a worse activity than going to a game.

But even with athletes sidelined and leagues suspended until further notice, sports are still playing a critical role in this crisis. And it’s one that, ultimately, is likely to end up being more meaningful than providing a few hours’ worth of diversion. So far, sports have been a funhouse mirror refracting us all. When a 7'1" pro athlete, age 27, is not immune to coronavirus, it is a good sign we all ought to take precautions seriously.

When entire leagues are closing shop, it’s a good sign we ought to be working from home as well. The multiples may be different, but athletes are worrying about their finances during this indeterminate period of unemployment. In living without sports, we realize we are living with sports. As Nets forward DeAndre Jordan said when spotted shopping for groceries in Brooklyn on March 14, “I’m in the same boat you are.”

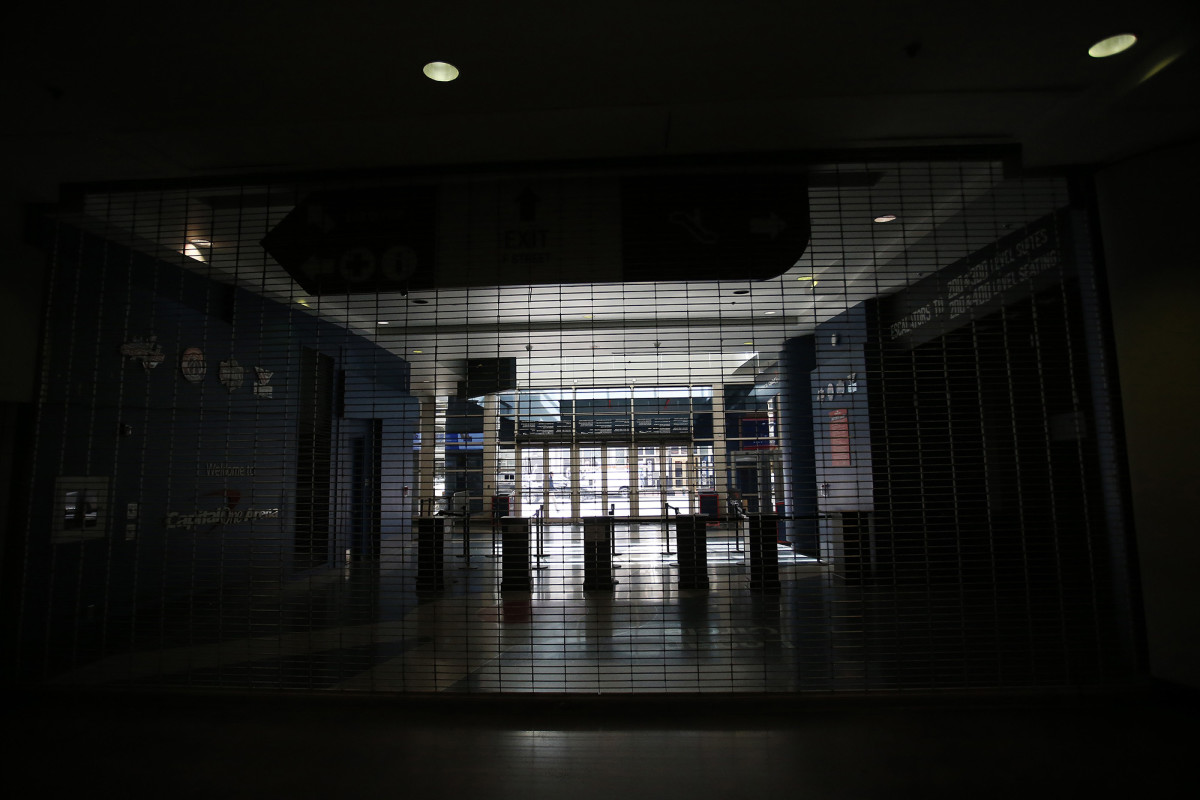

This crisis has shown that sports are not as bloated as we might think. Leagues today—and therefore athletes today—might make more revenue from media rights deals than from the folks going through the turnstiles and sitting in the stands. But the idea that sports have drifted so far into entertainment that games ought to be played on sound stages? That’s been disproven this month. Watch a game played in front of empty seats and it makes you appreciate how much texture comes from the folks who have paid for tickets—which athletes seem to know intuitively. As LeBron James was quick to put it, playing in a “closed door” arena would not be ideal: “Obviously, I would be very disappointed not having the fans, because that is what I play for.”

At the same time, sports have led, putting health, safety, and common sense ahead of commerce. When the organizers of the Indian Wells tennis event announced its cancellation on March 8, the eve of the tournament, the decision was criticized. Within a day, it was validated. When the Ivy League announced it would cancel spring sports, critics barely had time to clear their throats before most colleges in America were sending all students home.

In some cases, the collective response of sports is simply practical. Athletes share locker rooms, fly frequently, and their work is often predicated on close physical contact. (“Social distancing” is going to reflect poorly in your plus/minus.) What’s more, in recent years, sports has leaned toward relying on science and data and away from intuition. And then there is this: One of the great virtues of sports resides in the fact that, like life, it isn’t scripted or choreographed. A 35-year-old man can bounce back from a dismal season and become an MVP contender. World Series champions can disgrace themselves by stealing signs and conveying them by banging on garbage cans. One popular NFL broadcaster can make $1 million per game, while another can be the subject of a trade rumor. (And those are just examples ripped from 2020.)

In the sports culture of anything-can-happen, you come to respect the world of the unknown. And Lord knows that’s where we’re all living right now.