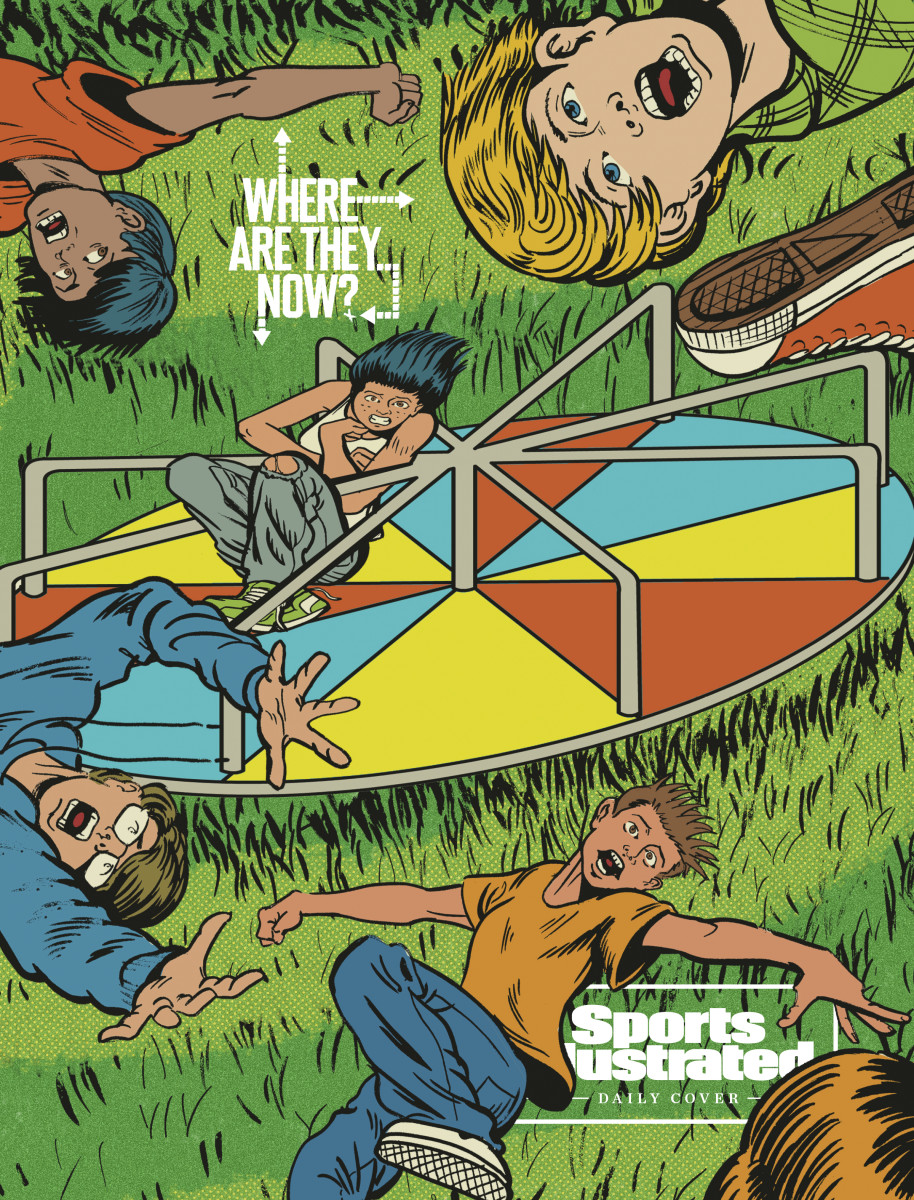

Hurl, Interrupted: What Ever Happened to the Playground Spinner?

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. Come back all week for more Where Are They Now? stories.

Of the many cheap highs available to grade school students of the 20th century—mimeograph ink, candy cigarettes, rails of pharmaceutical-grade Pixy Stix—the cheapest, highest and most easily obtained was dizziness. At birthday parties, kids were blindfolded, handed a deadly weapon and spun around before they staggered forth, disoriented, to batter a piñata or stab a paper donkey.

But dizziness didn’t require a special occasion. Dizziness was a party of one. Ricky Cobb was 7 years old in 1978 when he spun for fun in Horse Cave, Ky. “I remember having the time of my life just spinning, running, falling—the whole world moving,” says Cobb, who runs the popular Twitter account @Super70sSports. “I distinctly remember being in the front yard, spinning around a Wiffle ball bat just to see how dizzy I could make myself.” Before adolescence introduced its own gateway intoxicants, Cobb says, “self-induced dizziness was the best way to feel something in my hollow existence.”

And for most Americans, the nearest purveyor of public dizziness was the local playground, where one could board, at his or her peril, a piece of equipment known to industry professionals as a playground spinner and known to kids, variously, as a merry-go-round, carousel, roundabout or whirligig. These were the great steel platters on which a solitary child could rotate beneath a pitiless sun, like a Hot Pocket on a microwave turntable.

The Cadillac of spinners was the Miracle Whirl, created in 1927 in an Iowa glove factory by John Ahrens, whose son John sold it to the world. The Ahrens family didn't invent the wheel so much as reinvent it, laying it on its side like a steel lazy Susan that could eventually accommodate up to 40 kids. Shaped metal tubing acted as handholds, though these often proved illusory: When a large child (or chain-smoking grownup) got a playground merry-go-round spinning madly, every passenger became a straphanger on a commuter train plunging off a railroad trestle.

Spinners were physically powered by parents and other children, but metaphorically they were powered by joy and dread. It was a ride whose only emissions were laughter, screams and airborne 8-year-olds. And vomit. So much vomit. On an NBC special in 1970, when spinners were ubiquitous on U.S. playgrounds, the then beloved, now disgraced comedian Bill Cosby posited that the whirligigs of his North Philadelphia childhood could only have been conceived by oblivious adults: “Have you ever heard a kid say, ‘I want a toy where you ride round and round for five minutes [and] then throw up?’ ”

But that’s exactly what children wanted. In backyards (see: “Ring Around the Rosie”), at carnivals (where the Tilt-a-Whirl was better known as the Tilt-a-Hurl) and on any grassed embankment (ideal for barrel rolling beneath a blue sky), children were busy getting dizzy.

The Sit ’n’ Spin, originally produced by Kenner, was a plastic, single-seat spinner for home use that gained enormous popularity in the 1970s and ’80s, when children wore their vomit as a badge of honor. Its advertising jingle was simple and honest: “Sit and spin, sit and spin, sit and spin, kids just love to sit and spin.”

The playground spinner, then, was a Sit ’N’ Spin on steroids, not just in size but in temperament. These bigger spinners were weaponized, made malevolent, by other children. The object on most playgrounds was to turn the spinner so fast, for so long, that centrifugal force would expel small kids into the ether, one by one, like clay pigeons from a skeet trap.

Getting air wasn’t an entirely unwelcome experience. In King of the Mountain, youngsters ascending an Everest of plowed snow in a school parking lot were thrown off by the bigger kids at the summit, making the crisp winter air festive with flying children. And bailing out of playground swings at their apex allowed children to experience—for a fraction of a second, newly freed from the swing—the weightlessness known only to astronauts.

A Darwinian code prevailed on the playground, a law of the jungle that echoed in the names of the apparatuses: jungle gyms and monkey bars and Tarzan rope swings. City parks had tall slides with scalding steel surfaces and vertiginous descents that mimicked rappelling down the sheer face of El Capitan. Climbing the ladder to the top of such a slide was like ascending the high dive at a public pool: filled with anxiety; you could turn back, but not without great humiliation, and a lot of other children reversing down the ladder to accommodate you.

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

Spinners combined all of these thrills, fears and principles of natural selection into a single playground experience. Boarding a spinner full of larger children was an act of bravado, an effort to withstand G-forces that would make Chuck Yeager queasy. The very best among us simply held on for dear life. “If you were successful you would get sick,” says Cobb, a poet laureate of playground perils and other ephemera of the 1970s and ’80s. “The longer you could hang on, the greater the nausea.”

As a child, Cobb rode the spinner at the Twin City Drive-In movie theater in Horse Cave. There, he watched the world go by in a Waring blender, turning around him after dusk while Eddie Murphy in 48 Hours looked down from the big screen. It was a psychotropic experience powered not by LSD but by the multiple sloppy joes that Cobb, typically, had eaten from the concession stand. This death battle—sloppy joe vs. lazy Susan—was as dramatic and high-stakes as any flickering on the movie screen.

“There was always some a--hole older kid eager to get that thing up to maximum velocity,” says Cobb, now a father of five daughters in Elmhurst, Ill. “Some motherf----- was always happy to see how many 9-year-olds he could disperse across the playground. I don’t recall seeing a lot of parents there.”

How many turns could one unsupervised child endure before falling off or barfing? That’s the question Bart Simpson, literally the poster child of late-20th century American boyhood, wanted to settle when taking bets at the Springfield spinner on a particularly nostalgic 2015 episode of The Simpsons. “Fourteen spins and Wendell threw up!” Bart announced as weak-stomached Wendell Borton fought back a rising tide of vomit.

There were other perils associated with spinners. When 6-year-old Mark David Decker broke his right leg in the gap between the ground and the raised platform of the merry-go-round at Minges Brook Elementary School in Battle Creek, Mich., in 1962, his principal, Buford D. Grimes, “rolled up a Fortune magazine for a splint and tied it on with towels,” according to the local newspaper, a quaint reminder of a time when there was always a magazine at hand, and a local newspaper, and a principal trained in battlefield triage.

“Kids getting thrown off right and left,” Cobb tweeted last spring along with a photograph of a playground spinner that got 25,000 likes from his half million Twitter followers. “Total carnage. Wails of anguish. Not one adult gave a single s--- about it.”

Young kids on the spinner, and older wusses, were advised to stay in the center of the circle. The truly daring would “wrap our legs around the poles and then hang our heads off the edge as it spun, inches from the ground,” as one of Cobb’s followers replied. “Nope, no one stopped this extraordinarily stupid activity.”

For better and worse, parental indifference was a hallmark of that very different era. As one advertisement in 1953 boasted: “Now youngsters of all ages can amuse themselves by the hour without supervision on the Lifetime Miracle Whirl!”

To be fair, adult supervision didn’t always help. In 1968, a teacher in Oregon was hurrying to the merry-go-round at West Stayton Grade School, urgently warning children to slow it down, when centrifugal force did what it has always been compelled to do: It slung a child from the speeding spinner like a ball from a roulette wheel. The teacher, Lois Lancaster, could not avoid the airborne child, who knocked her to the ground. Lancaster was taken to Santiam Memorial Hospital, where she was listed in satisfactory condition with a broken knee.

That October, in a New York City recording studio, David Clayton-Thomas sang: “What goes up, must come down / Spinning wheel, got to go ’round.” That song, “Spinning Wheel,” would become the first hit for a band called, appropriately, Blood Sweat & Tears. Soon, people all over the world were singing its laissez-faire lyrics, with a lesson that Mrs. Lancaster learned the hard way: “Let the spinning wheel spin.”

Marilyn Monroe and photographer Eve Arnold stopped, spontaneously, at a playground near a beach on Long Island one day in 1955, the summer of The Seven-Year Itch. Arnold photographed the movie star lying prone in a candy-striped swimsuit on a candy-colored spinner, looking pensive, or possibly nauseous. Either way, here were two American icons—spinner and starlet—of the 1950s, when a great many of the spinners were installed, and many of those at drive-in movie theaters.

Twenty-five years later, when Ricky Cobb was spinning at the Twin City Drive-In, those spinners were already artifacts from a distant, space-age past. That space age spawned the Miracle Dome Whirl. A variation of the Miracle Whirl, the Miracle Dome Whirl looked like the nose cone of a rocket ship pointed at space, but with 16 fluted spaces on the side, each of which accommodated a standing child, clinging to a single metal handhold.

In Bloomington, Minn., these red-and-white attractions were called Bomb Pops, because they looked uncannily like the missile-shaped, Cold War–themed popsicles of the same name and era. The stakes were raised on the Miracle Domes, because children couldn’t see their counterparts on the other sides, and thus didn’t know who might suddenly propel it faster or bring it abruptly to a stop or reverse its course the way Superman stopped time by inverting the rotation of Earth.

I spun on those Bloomington Bomb Pops, as did my childhood best friend, Mike McCollow, on the playgrounds at Hillcrest and Indian Mounds, respectively. Children used their own leg power to push and then jump on, but when powered by a larger kid or a passing grownup, the wheel would fly with the fearsome joy of a contestant spinning for the Showcase Showdown on The Price is Right. “You had different levels of thrill seekers on the same ride,” says McCollow, who grew up in Bloomington in the 1970s and ’80s. “On one side: a girl gently Fred Flintstone-ing it with one toe,” he says, referring to the cartoon caveman who powered his sedan with his own unshod feet. “On the other side: a high school linebacker walking by could give it the full Wheel of Fortune spin before jumping on.”

Sometimes a child stood on top of the spinning dome. More often they lay star-fished on their stomach, rotating beneath God until they slid off. (A drunk person with the bed spins knows the feeling.) Braver still was any kid who spread-eagled on their back, like Da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man, and watched heaven and earth rotate around them.

When a spinner was really spinning fast, a child could hang on one-handed and get horizontal, like a flag in a gale. Losing one’s grip had consequences, for the ground beneath our feet was “not the Nike rubber-pellet trampoline surface of today,” McCollow notes, rather a composite of broken glass, broken teeth, broken spirits, cigarette butts and, always, for reasons we could never discern, a single wet sock.

Today’s playground equipment, by contrast, is largely stationary and low-slung. Slides of high-density polyethylene are gently sloped and make a child’s arm hair stand on end not with terror or excitement but with static electricity. He or she will gently alight onto a primary-colored cloud of rubber. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission recommends that playground surfaces are “at least 12 inches of wood chips, mulch, sand, or pea gravel, or are mats made of safety-tested rubber or rubber-like materials.”

But even the City of Bloomington seemed to lament the disappearance of the spinners from its playgrounds when in 2020 its website posted a photo of a Miracle Dome with a caption that noted the “telltale ring of footprints” around the equipment and observed that “even during winter, kids enjoyed the thrills, spills and dizzy delight.” Then, as if snapping out of a nostalgic daydream: a sobering coda, almost a disclaimer. “The spinning dome was removed more than 30 years ago. These days playground equipment offers safer experiences for children.”

With those old merry-go-rounds, children tended to run against the direction of the spinning platform, guided by the same impulse that impelled them to bound up a slide, or walk on top of a jungle gym, or stand up on the swings or ascend the down escalator. There is a body of scientific evidence suggesting that challenging playground equipment ignites creativity, fosters independence and helps children navigate danger. “The playground has become so safe,” writes Susan G. Solomon in her rigorous history, American Playgrounds: Revitalizing Community Space, “that it no longer allows children to take on challenges that will further educational and emotional development.”

Ahrens, inventor of the Miracle Whirl, died in 2000 after reaching dizzying heights in the spinny-ride industry, but by then he had already come to that same conclusion: “If all playgrounds were 100% safe, children wouldn’t use them. Kids want action, and if there’s no challenge, they won’t use the equipment. They learn a lot from little bumps and bruises. They learn to recognize dangers and they learn personal responsibility.”

Spinners, in hindsight, inspired more confidence than those backyard swing sets hastily assembled by highball-wielding Dads, still in their neckties—the sets that rocked back and forth in tandem with the swinger. Playground swings, by contrast, were as permanent as City Hall, with rubber seats that resembled weightlifter belts, though they were often occupied at odd hours by high school kids. The city tennis courts, scored with skid marks from muscle bikes, often served the same purpose: an after-hours hangout for burnouts. In many places, they still do.

For children seeking the more innocent buzz of self-induced dizziness, there are modern playground spinners, including the popular Supernova, a spinnable ring tilted at 10 degrees. A rider must remain balanced on its edge, as if walking a circular plank. The manufacturer, Kompan, says of the Supernova: “Rough-and-tumble play is on, and the pushing of the ring … train[s] the children’s arm and leg muscles and cardio. The jumping on and off of the rotating ring builds bone density. The Supernova trains the sense of balance and space, which is crucial for being able to sit still or navigate traffic safely. Children help one another and invent games.”

It is something to be hoped for—children helping one another on a playground spinner—though it isn’t always evident in practice. As for the old-school spinners: Like Marilyn Monroe, the kind of spinner she posed on has become a symbol of lost innocence. The young meth dealer Jesse Pinkman rotated beneath the stars before dawn on a squeaking spinner on an Albuquerque playground in the fifth season of Breaking Bad. Here were two purveyors of cheap highs, one slightly more sinister than the other.

And so most of the old spinners have long since been removed from playgrounds in a risk-averse, lawsuit-preempting, decades-long march toward safer equipment on softer surfaces, in compliance with Consumer Product Safety Commission guidelines. In 2014, New York City removed several spinning rides from public playgrounds and welded another into place, so that it couldn’t rotate, as if stopping the hands of a clock.

But the seasons still turn, turn, turn, like the earth itself, time not marching on or flying so much as repeating itself. Time is a flat circle, in Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence, which is to say: Time is a playground spinner. There are as many playground injuries today as there were 50 years ago, about 200,000 annually, according to the CPSC (though this does not account for an increase in the overall number of playgrounds).

Like the lunar rovers abandoned on the moon, a few ancient spinners do survive across the U.S., reminders of another age, when a child fresh from dinner, waiting for the local drive-in’s sundown showing of Plan 9 from Outer Space could spin joyously on the Miracle Whirl, like a 45 record of “All Shook Up,” which aptly described the contents of their stomachs.

That song was number one in 1957, the same year the Wellfleet Drive-In opened on Cape Cod with a showing of Desk Set, starring Katharine Hepburn. Sixty-five years later, that drive-in is still thriving in summer, full of vacationers watching retro blockbusters like Jaws and E.T. in a place beyond time, where mini-golf and soft-serve ice cream follow fish dinners served on Frisbees, and children still while away the minutes before the double-feature on the drive-in’s vintage playground spinner. It is there now, spinning inexorably, a perpetual clock not marking time so much as eluding it.

Read More ‘Where Are They Now?’ Stories:

• John Amaechi: ‘You Want Gay People to Come Out: Make It So It’s Not S----y’

• Steffi Graf Is Still Too Famous For Steffi Graf

• The GOAT Abides: Gary Smith, the Sportswriter in Repose