My Sportsman: Anthony Robles

Sports Illustrated will announce its choice for Sportsman of the Year on Dec. 5. Here's one of the nominations for that honor by an SI writer

When you are born with only one leg, you get knocked down a lot, literally and figuratively.

Anthony Robles has taken more than his share of falls, from the time he learned to ride a bike at age 5, to the time he played defensive tackle for his junior high team at 14, to the day he took up wrestling as a high school freshman, all without the benefit of a right leg.

He took a different kind of tumble in March of last year, when he was the No. 4 seed at the NCAA wrestling championships with a 28-2 record in the 125-pound class but fell short of his goal of winning the title, finishing seventh.

I met Robles about a week before that tournament when he was a junior All-America at Arizona State.

He was so passionate about winning the NCAA title that he closed his eyes as he talked about it, seeing it in his mind's eye. How important was it to him?

"It's all I want," he said. "It's all I think about. I believe I'm going to win. I believe it with all my heart."

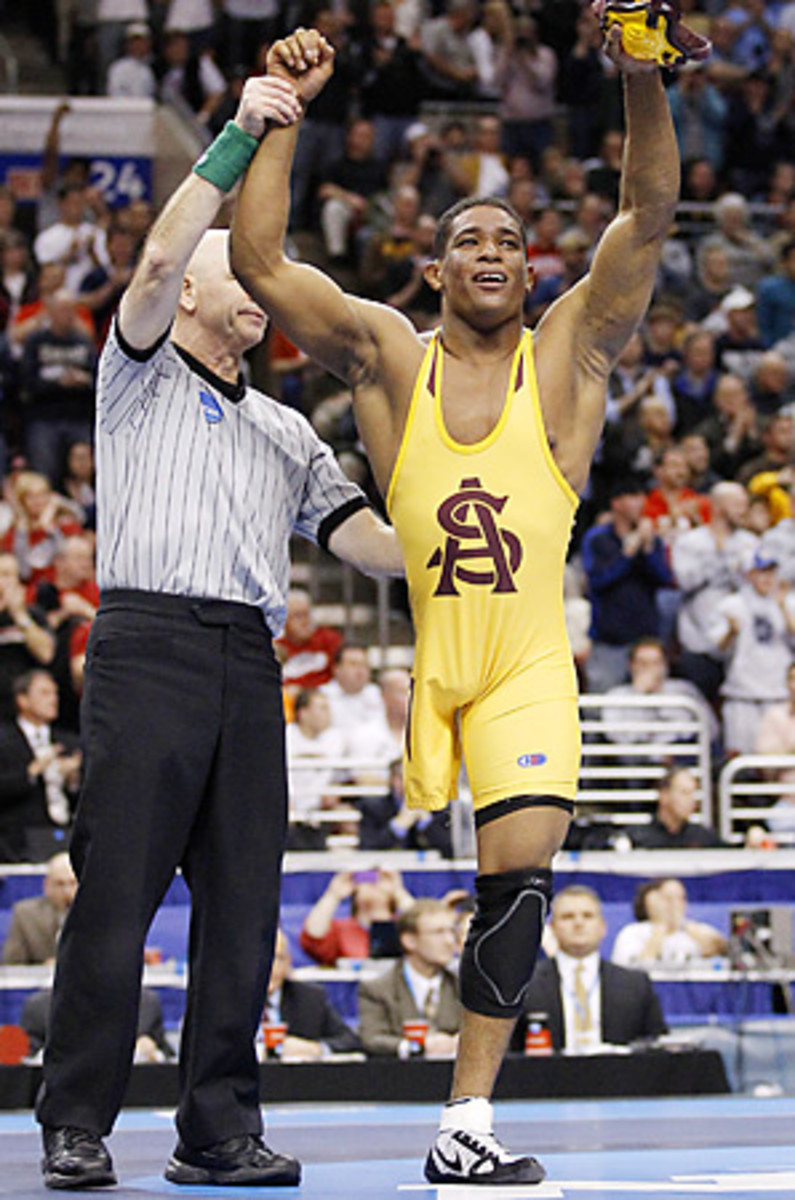

He didn't win, of course, but Robles did what he's done all his life after taking a fall. He got up again. He went back to the NCAAs last spring as a senior, and this time, he came away with the championship that he wanted so badly, not to mention a 36-0 record and the tournament's Most Outstanding Wrestler award. But it isn't just the championship and the honors that make Robles a worthy candidate for Sportsman of the Year -- it's all the times he kept getting up again.

Robles was born with his right leg missing all the way up to the hip, an abnormality his doctors have never been able to explain, according to his mother, Judy. He was an active kid who found that a prosthetic leg slowed him down, so he chucked it when he was seven and has been using crutches or hopping on his unbelievably powerful left leg ever since. He tried wrestling just like he tried almost every other sport, and at first he was awful. Opponents flung him around with ease.

"The only time I'd win was if the other guy got sick and had to forfeit or something," he said.

But slowly he got stronger through maniacal weight-room work -- so strong that at 5-foot-8 he now has the upper body of a mini-Schwarzenegger -- and he learned better technique, including going to the ground immediately at the start of the match, where his opponent wouldn't have such an advantage in balance. Win or lose, he won admiration from everyone who watched him wrestle, and sometimes he even brought them to tears with his perseverance.

Once, when his coach at Mesa (Ariz.) High, Bob Williams, was unhappy with the team's performance at a meet, he had them run laps while holding 20-pound sandbags as punishment. Williams didn't intend to include Robles, but before he could stop him, Robles was hopping around the track on his left leg, holding a sand bag. He quickly fell, then got up again. He hopped a bit farther, then went down again, and rose again. On it went -- hopping, falling, and getting up while his teammates ran. Robles didn't stop until the rest of the team did.

"It was amazing, the way he wouldn't give up, wouldn't give in," Williams said. "There were some misty eyes in the gym that day, including mine."

And that's why I shouldn't have felt so bad for Robles last year when I read that he had -- temporarily, as it turned out -- fallen short of his goal to win the NCAA title. I should have realized that to him, it was just another fall, and that Robles would simply get up again. He always does.