Chronicling LeBron's career

LeBron James appeared on his first Sports Illustrated cover as a 17-year-old high school junior in 2002. More than 10 years later, he graces the cover this week as SI's Sportsman of the Year. In between, the magazine has tracked his emergence as the best player in the NBA, his messy departure from Cleveland, his humbling loss with Miami in the 2011 Finals and his redemption 12 months later. With James being honored for a year in which he collected his third MVP award, won his first NBA title and led Team USA to an Olympic gold medal, five writers reflect on their experience covering LeBron and trace his evolution over the last decade.

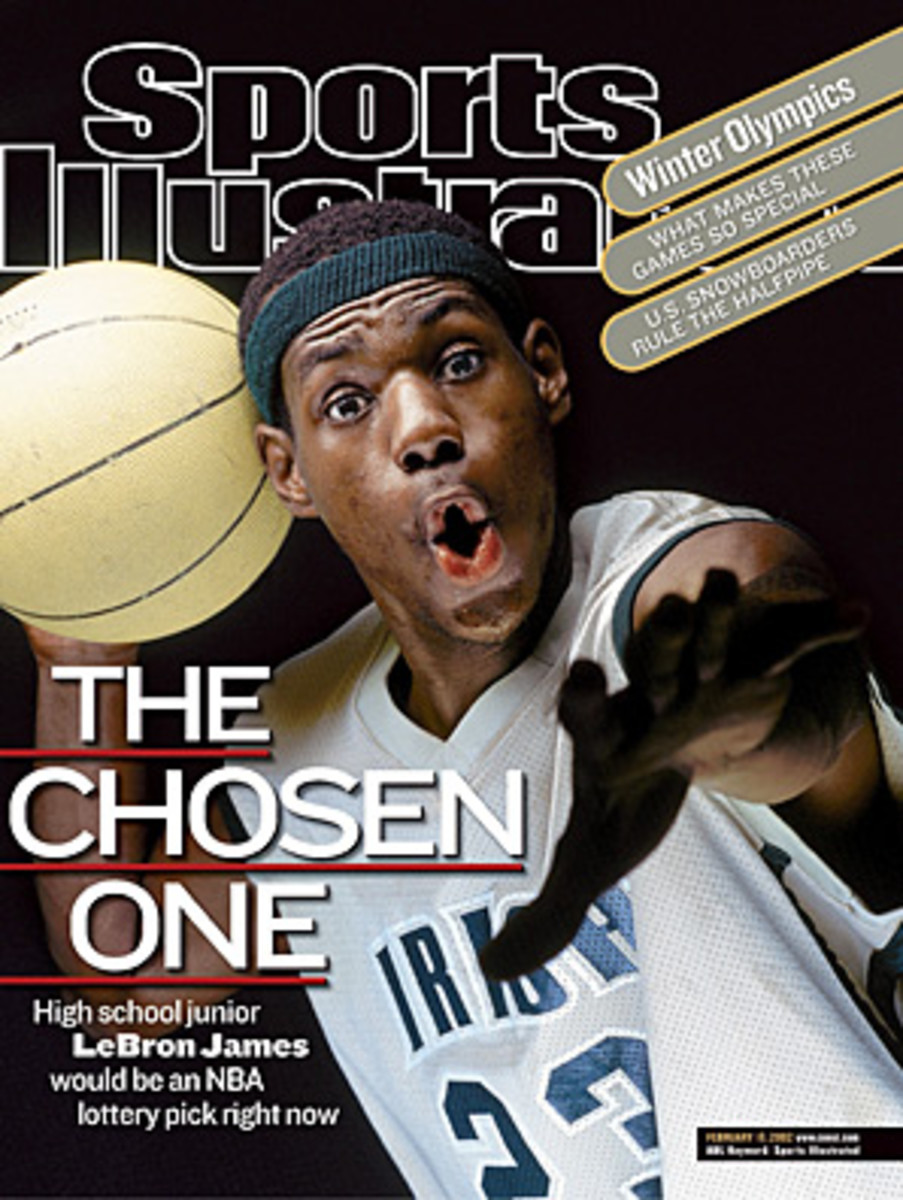

The way I remember it, the make-or-break moment for "The Chosen One" cover story on 17-year-old high school junior LeBron James took place in the locker room of James' high school on a cold winter day in January 2002. I had just parachuted into Akron, Ohio, for SI, and I could tell that he wasn't entirely happy about my coming in on short notice. Finally, I asked him: "LeBron, could you come over for one second?" We walked over to a quiet corner. "I'm sorry we didn't let you know about this any earlier, but this story could be a pretty big one in the magazine. There's a good chance you'll be happy with the results."

LeBron thought about it for a second, nodded and smiled. And from that point I was in. The rest of the day was a blur of images: visiting his small West Akron apartment and having LeBron proudly show off the throwback jerseys in his closet. Meeting his buddies and watching their favorite video, the Wayans brothers' parody Don't Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood. Noting the fake SI cover of LeBron on the top of the living-room television: IS HE THE NEXT MICHAEL JORDAN? Eventually we all piled into my small rental car -- me, LeBron and his buddies Maverick Carter, Brandon Weems and Frankie Walker -- for the hour-long drive to Cleveland for the Cavaliers-Wizards game that night. LeBron brought a binder full of his favorite CDs and blasted Jay-Z most of the time.

On the way, we stopped at a McDonalds drive-thru, and as we waited I turned to LeBron next to me and casually mentioned: "You know, this has a chance to be a cover story." I won't forget the look he gave me, a wide-eyed stare followed by a nod that showed he understood what that meant. SI senior editor Greg Kelly already had the idea for the cover line -- THE CHOSEN ONE -- and LeBron would eventually like it enough to get a tattoo of the line. That night LeBron rooted for the Wizards and his idol, Michael Jordan, who hit a last-second game-winning shot (of course). And afterward something fascinating happened. We met a guy in a fantastic suit, a guy whom LeBron and Maverick called "Uncle Wes." It would turn out to be William Wesley, aka Worldwide Wes, the great social connector of the basketball world. Uncle Wes brought out Jordan, and as 17-year-old LeBron and His Airness talked I lurked a few feet away and felt like I was witnessing the hoops equivalent of that old photo of John F. Kennedy with a young Bill Clinton. The scene ended up being the lead of my SI story.

We drove back to Akron that night, LeBron serving as the deejay in my crappy rental car and being thoroughly entertaining with his pals. (At one point, LeBron taught me the meaning of the slang word janky.) We finished off the evening with a late dinner at Applebee's, where LeBron could still eat with a few friends and not have to worry about being accosted for autographs. A couple weeks later he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated -- the real one, not a fake one -- and his life would never be the same.-- Grant Wahl

***

Grant Wahl on high school phenom LeBron James, in a 2002 Sports Illustrated story:

"All things considered, it's hard to decide what's more impressive -- that LeBron could be hailed as the best high school player even though he's only a junior, or that many NBA scouts believe he would be the first pick in this year's draft (if league rules didn't forbid his entering it), or that he can get an audience with [Michael] Jordan as easily as a haircut appointment.

"Then again, the world behind the velvet rope is nothing new to LeBron. Last summer he was the only schoolboy invited to play in Jordan's top-secret workouts in Chicago. LeBron speaks regularly with Boston Celtics star Antoine Walker, who is his best friend among NBA players. Those floor tickets to the Cavaliers game? LeBron's surrogate father, Eddie Jackson, simply made a call to Cleveland coach John Lucas. Already LeBron has hung out with Michael Finley, Tracy McGrady and Jerry Stackhouse, to say nothing of his favorite rapper, Jay-Z. 'He's a cool guy too,' LeBron says. 'We went to his hotel first, and then I had backstage passes.'

"Did we say LeBron just turned 17?"

Click here to read the full story.

In the grand scheme of LeBron's career, the game doesn't mean much. He may not even remember it. But during the 2005-06 season, when I was following the Phoenix Suns for a book, I got an inside look at how one team prepares for one player, and how sometimes all that preparation just doesn't matter if it's a player like LeBron James.

James was at that point still a work in progress, albeit a formidable one in his third season. The league may have seen what was coming before he did, lodged as he was in the confusing game of being both Young Teammate and Franchise Megastar for the Cleveland Cavaliers.

"LeBron will go through this streak when he makes everything, and I mean everything," assistant coach Marc Iavaroni said in a pregame meeting among the coaches. "We just gotta ride out those hover jump shots he makes because we do not want him breaking us down."

As the coaches saw it, LeBron had already achieved superstar status among the refs, a reality that influenced their defensive strategy, in this case making sure that the established Shawn Marion guarded LeBron, instead of the little-known Boris Diaw, when James moved to power forward.

"They'll call a foul on Boris," assistant Alvin Gentry said, "before they'll call one on Shawn."

Added Iavaroni: "And remember LeBron leads the league in and-ones."

Phoenix's main hope is that LeBron will "settle," i.e., take outside shots instead of drive to create fouls.

Well, LeBron rarely settled. And when he did, he usually made a perimeter jumper or fed a teammate for a basket. I remember thinking that I had rarely seen one man do so much so effortlessly. Anyone who covers sports knows how false the phrase "one-man team" is, but this came damn close.

James had 23 points at halftime, yet the coaches actually praised the joint effort done on him by Marion and Raja Bell. They spent the entire halftime session trying to figure out what to do to stop him, and finally head coach Mike D'Antoni just summed it up: "LeBron is just kicking our ass."

The Suns didn't fare much better in the second half trying to stop him, though they were the superior team and won 115-106. James finished with 46 points, including five three-pointers, eight assists and seven rebounds. Even the partisan Phoenix crowd was applauding him by the end.

"He's like Jim Brown on a basketball court," Gentry said. "Only way I can think to describe it."

Everyone was still talking about the game the next day at Suns practice. Let's be clear that no one would've been happy had they lost. But they won and so it was possible both to be happy and marvel at the skill of an opponent. (Indeed, two weeks later, James scored 32 of his 44 points in the second half as the Cavs rallied from a 17-point third-quarter deficit to beat Phoenix 113-106 in Cleveland.)

"LeBron is real tough to play," Marion said. "Still, I don't know what it looked like from where you were, but that was a fun, fun game to be in."

It looked the same from where I was, Shawn.-- Jack McCallum

***

Jack McCallum on an 18-year-old LeBron James, set to make his NBA debut, in a 2003 Sports Illustrated story:

"NBA officials will tell you that we've seen this before, a phenom receiving big bucks, arriving amid much fanfare. But they're kidding themselves and they know it. No one has gotten this much this soon, no one has ever entered any league under so much scrutiny. The three-year, $10.8 million rookie contract he's getting from the Cavaliers is Monopoly money to James, who has endorsement deals worth more than $100 million. 'I've been around the game for 40 years,' says Cavs coach Paul Silas, 'and I've never seen anything like it. It's scary.' "

Click here to read the full story.

I first met LeBron in 2006. A number of things struck me: his basketball IQ while watching film, how polished (yet unrevealing) he was talking to the media, how his teammates deferred to him even though he was young. But the two biggest impressions were 1) his "team," which struck me as preposterous. For a 45-minute interview, James was accompanied by the better part of a dozen people, including PR folks, cronies, a personal stylist and his personal media guru (separate from the Cavs), who'd flown in from New York for the occasion. Did he really need all this?

In retrospect, it makes sense: surround yourself with this many yes men and women and one day you wake up on a TV special called The Decision. And 2) despite all his attempts to act like a CEO, he was still just a kid at heart. This became clear when our photographer, Michael LeBrecht, straddled James to get a portrait shot. At which point LeBron ripped off a long, stuttering fart, then began cackling like crazy.

In 2009, I saw a different LeBron. Supremely talented and supremely confident, perhaps overly so. Now he spoke like a man, acted like a man. More than anything, though, what struck me was his size. We set up an interview at the St. Regis hotel in San Francisco in January. During the previous weeks and months, there'd been much conjecture about LeBron's weight. He looked like a linebacker, all muscle and thick shoulders. There were whispers of 270 pounds, perhaps higher, but James refused to provide a number.

I was curious about two things: if he was indeed that big and why he was reluctant to discuss it. So I brought an electronic scale to the interview, but James wouldn't get on (a Cavs staffer later told me his weight was between 265-270). To me, this was LeBron in his second phase: hoping to create his own legend, looking to control as much as possible.

***

Chris Ballard on LeBronatomy 101, in a 2009 Sports Illustrated story:

"This is sure to exasperate scrawny teenagers toiling in weight rooms the world over, but despite his bodybuilder's physique, James has never really lifted. At least not the way a normal human would to develop such musculature. (Think heavy weight, low reps, lots of grunting and Metallica.)

"Rather, James began working out seriously only last June. 'He just messed around in the weight room and got by on raw strength his first few years,' says Cavs trainer Mike Mancias, who oversees all of James's conditioning work. Even now, James eschews what he calls 'iron-man championship lifting,' such as the bench press, for core exercises, dumbbells and, starting last summer, yoga� not that he was an easy convert. 'I had to start with poses he wouldn't think were too goofy, if you catch my drift,' says Mancias. Still, there was James at a hotel in Los Angeles last summer, busting out some downward dog by the pool in front of his fellow guests.

That James has gained weight is as much a mystery to him as anyone else. He doesn't gulp protein shakes or pound down extra carbs, instead eating three square meals (such as oatmeal, chicken, salmon) prepared by his chef, with the occasional candy snack in between. 'It's kind of crazy,' James says. 'My body's, like, reversed.' "

Click here to read the full story.

Dirk Nowitzki had on a white T-shirt that stunk of champagne and a championship cap he wore as if he were a 12-year-old in a fireman's hat. He walked down the hallway of the arena in Miami with a bottle in his right hand and the Finals MVP trophy upside down in his left. He was the one who had arrived.

It was the final night of the 2010-11 season and LeBron James was headed out the door with no smell of liquor about him. He wore a blue suit and a gray tie and an unhappy expression of business. Dallas had won the NBA championship at his expense. Nowitzki was the winner and James, for what would be the last such season of his career, was on his way home once again as the loser who didn't yet understand how it felt or what it took to be a champion.

"LeBron, given your performances late in games in these Finals, what's your assessment of your ability to play well under pressure?''

"Does it bother you that so many people are happy to see you fail?''

"Do you take this as a personal failing?''

"Do you feel you choked in this series?''

The questions were aimed one after another at James, part of the same cruel process that had made a champion of Nowitzki. The years of postseason losses and frustrations hardened and inspired him. The same kinds of defeats -- magnified by James's self-destructive exit from Cleveland to Miami -- were going to have the same kind of constructive impact on LeBron.

"I've been in this league eight years,'' James said at the end of his first season in Miami. "There's no distractions that can stop me from trying to chase an NBA championship. Not you guys, not anything that goes on that's not focused on my team and my teammates and what we're out there to do.''

He was talking faster. He was scowling, seething.

"I work hard to try to put myself in position to play at a high level,'' James went on, managing his emotions yet letting them be seen. "I put a lot of hard work into this season individually. We all did. So we have nothing to hang our heads low. Just use this as an extra motivation to help myself become a better player for next year.''

Nowitzki was dressed to celebrate, with his bottle in one hand and his trophy in the other. For James, the goal would be to follow the path of Nowitzki and turn his pain into a celebration one more year away.-- Ian Thomsen

***

Ian Thomsen on the challenged that faced the new-look Heat at the start of the Big Three era, in a 2010 Sports Illustrated story:

"Last summer's most persistent question -- will the three biggest free agents play together? -- was answered by James in a July 8 live infomercial that in 60 minutes deeply depleted seven years of brand equity. But the practical question remains unanswered: How will they play together? Each has grown up as the face of his franchise (small forward James of the Cavaliers, power forward [Chris] Bosh of the Raptors, shooting guard [Dwyane] Wade of the Heat), which left them feeling empowered enough to thumb a collective nose at NBA tradition and pull off their megamerger. They each wore white to the wedding and danced together onstage in July for 13,000 guests at the reception in Miami, and that was the fun part. Now comes the grind, the details, the tricky task of making their union work for everyone."

Click here to read the full story.

For 43 minutes, it was an entirely forgettable game: Heat-Nets, on a Monday night last April at the Prudential Center in New Jersey, one team safely ensconced in the playoffs and the other hopelessly out of it. Dwyane Wade didn't play and LeBron James didn't play particularly well, at least not for those first 43 minutes. He was booed, the same way he was booed everywhere, and the Heat appeared headed to an embarrassing but ultimately meaningless loss.

People always say you only need to watch the last five minutes of an NBA game, and though I strongly disagree, that night in New Jersey helps prove their point. With five minutes left in the fourth quarter, and the Heat down by five points, an unstoppable force appeared. Before the game, I'd asked New Jersey's DeShawn Stevenson what it's like to guard James when he gets a running start. "Like standing in front of a train," Stevenson said. That's what James became at the five-minute mark: an Amtrak off the rails.

He scored 17 straight points, virtually all of them on drives and post-ups, none more than five feet from the basket. Even the Nets' fans stood and cheered. They snapped pictures with their camera phones. MVP chants filled the air. No one confused the Nets with the Thunder, but it was still an NBA game, and James simply decided he was going to take it over. Anybody at the Prudential Center that night left with a pretty good idea of what was going to happen two months later. James finally understood what so many of his peers recognized long ago. When he attacks the rim, no one can keep him from it.

After the game, James walked over to Jay-Z's nephew in the front row and slipped his headband around the boy's neck. Then he took off his sneakers and gave those up as well. On the way to the locker room, he asked, "Does this work?" I'd interviewed him two days before at a hotel restaurant in Jersey City and he reflected on the changes he made after The Decision and the NBA Finals loss to Dallas. He talked a lot about rediscovering his joy for basketball. Standing there, in his socks, he had clearly found it. -- Lee Jenkins

***

Lee Jenkins on newly crowned NBA champion LeBron James, in a 2012 Sports Illustrated story:

"James has grown in front of the world's eyes, through Technicolor lenses on high-definition flat screens, from a prodigy in Akron, Ohio, to a colossus in Cleveland to a polarizing sun god in Miami. At 4:15 a.m. last Saturday, as James struggled to sleep, he felt himself enter a new stage. 'It just finally hit me,' he wrote in a text message to Maverick Carter, his childhood friend and business manager. 'I'm a champion.' Twelve hours later, James sat under overcast skies on the Ritz terrace, wearing a white T-shirt with the slogan EARNED NOT GIVEN and sipping a Sprite. He was still sleepless and in no hurry to nap. 'I'm having all my best dreams wrapped into one,' he said.

"Pressure remains, the burden of the supernaturally gifted, but in a different form. All the breathless questions that hounded James since the Cleveland days -- Can you close a game? Can you lead a team? Can you win a title? -- are gone, sunk at the bottom of Biscayne Bay. "It's time to make a new challenge," James says. 'I've got to figure out what that is. I know I can get better. And I know I'm not satisfied with one of these.' Twenty-nine teams should be very afraid, because James has breached the championship levee, just as Michael Jordan did in 1991. Jordan was 28, and he won five more titles in the next seven years, even with a break for baseball. James is 27, and for the first time he will get to play without a baboon on his back. 'With freedom,' Heat president Pat Riley says."

Click here to read the full story.