Warrick Dunn's Greatest Legacy Goes Far Beyond Football

Over the past 23 years, 174 low-to-moderate income, single-parent families in 18 cities spread across 11 states have walked for the first time into the first houses they have ever owned, expecting them to be empty. So it is always a surprise for the new homeowners, one which usually moves them to tears, when they discover that the rooms have been fully furnished and decorated, that the cupboards and refrigerators are stuffed with food and cookware, and that the closets and garages brim with cleaning supplies and lawncare equipment. While the furnishings are tailored to the needs of each family, almost all of them have been greeted by the same three things: an oversized check for $5,000 to help with the down payment; the smiling face of the NFL’s 23rd all-time rushing leader; and, in a glass dish on the dining room table, a fresh apple pie.

“Apple pie means home, and the American dream,” says 44-year-old Warrick Dunn, the former Falcons and Buccaneers running back who helped all 174 families—170 led by single mothers, and four by single fathers—find both through his Atlanta-based charity, Homes for the Holidays. All of the families have first been accepted by an affordable housing provider, most often Habitat for Humanity, which among other things requires prospective homeowners to contribute several hundred hours of sweat equity into their houses’ construction, and to take classes in financial literacy and basic home repair. Then Dunn collaborates with the organizations to identify families who could most use his additional surprise boost—the furnishings and down-payment assistance that ensure a truly fresh start.

Some of the families, like Rickita Burney’s, used to live in constant fear. Her old Atlanta-area apartment was ransacked twice in one month in 2014, traumatizing her son Khali, now 15, and daughter Zariya, now 11. The Burneys became the 151st family to benefit from Dunn’s program, in November 2016, and three years on they still live peacefully in a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house on a corner lot in the leafy suburb of Jonesboro. “He doesn’t want anything back,” says Burney, who works in jail administration. “Just to see that the family’s happy, and living their best lives.”

All of the families once faced a threat even more perilous than crime and violence: instability. Steady housing is one of the hardest things for single parents to provide. Children of families with incomes below the federal poverty level were more than four times as likely to have experienced five or more moves than children in families with incomes of twice the federal poverty level, according to a 2012 study. And in having to move often, they end up forcing their children to regularly reestablish friendships and support structures.

“In an apartment, you know, after six or eight months your lease is up and you’ve got to find another,” says Tia Merriweather, who in 2005 became the 56th recipient of one of Dunn’s surprises along with her sons Cyril, now 24, and Aubre, now 20. “You’ve got to go through all that stress.” Back then, Merriweather, a medical office administrator, had to take on a second job, as a weekend home assistant for the elderly, to make the $850 rent—but that meant that she was constantly worried about arranging care for her children.

That all changed once her family arrived at their new townhouse in Roswell, Ga., which Dunn had outfitted. “It was pretty much like all we had to do was go get our clothes and move in,” Merriweather says. Although he was only five, Aubre still remembers the day. “I was like, how could this have happened to my family?” Aubre says. “You hear about these kinds of things on TV, but you don’t really expect it to happen to you.”

Dunn’s program is not intended to provide winning lottery tickets. “When a parent gets a home, most people think, Oh, he just gave it to them,” Dunn explains. “No. They’ve actually done the work. They had to clean up their credit, get approved for a loan. They actually make monthly payments on the home. What we do is we come in and we help ease the burden a little bit. Because what I’ve learned is that when you try to fully furnish a home, you go right back into debt. If you want to help people have a true fresh start, you want to give them a push down the road, but they have to continue doing the work.”

The push usually amounts to about $40,000 between the down payment assistance and furnishings, some of which comes from donors and some of which comes from corporate partners like Aaron’s, a lease-to-own retailer. That push, though, can make all the difference: Dunn says some 92% of the families he has assisted remain homeowners, either of their initial dwellings or subsequent ones. “We are all starting at different points in life, so it’s important that we assist these families and really give them a hand up, not a handout,” says Whitney Jackson, the executive director of Warrick Dunn Charities. “We’re all trying to get to the same finish line.”

It’s a story Dunn knows personally. While his mother, Betty Smothers, was a Louisiana state champion in the high hurdles, homeownership and the resulting stability was one finish line that she could never quite reach.

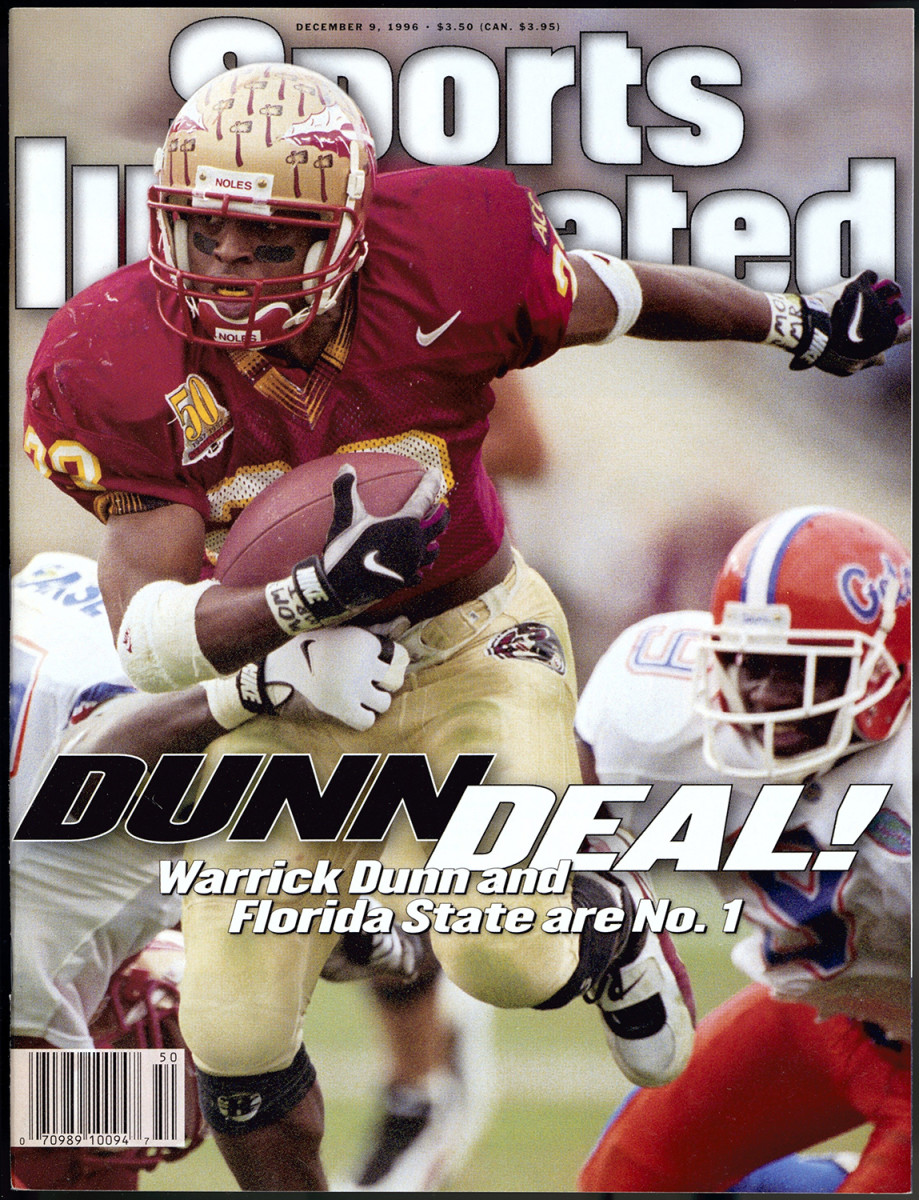

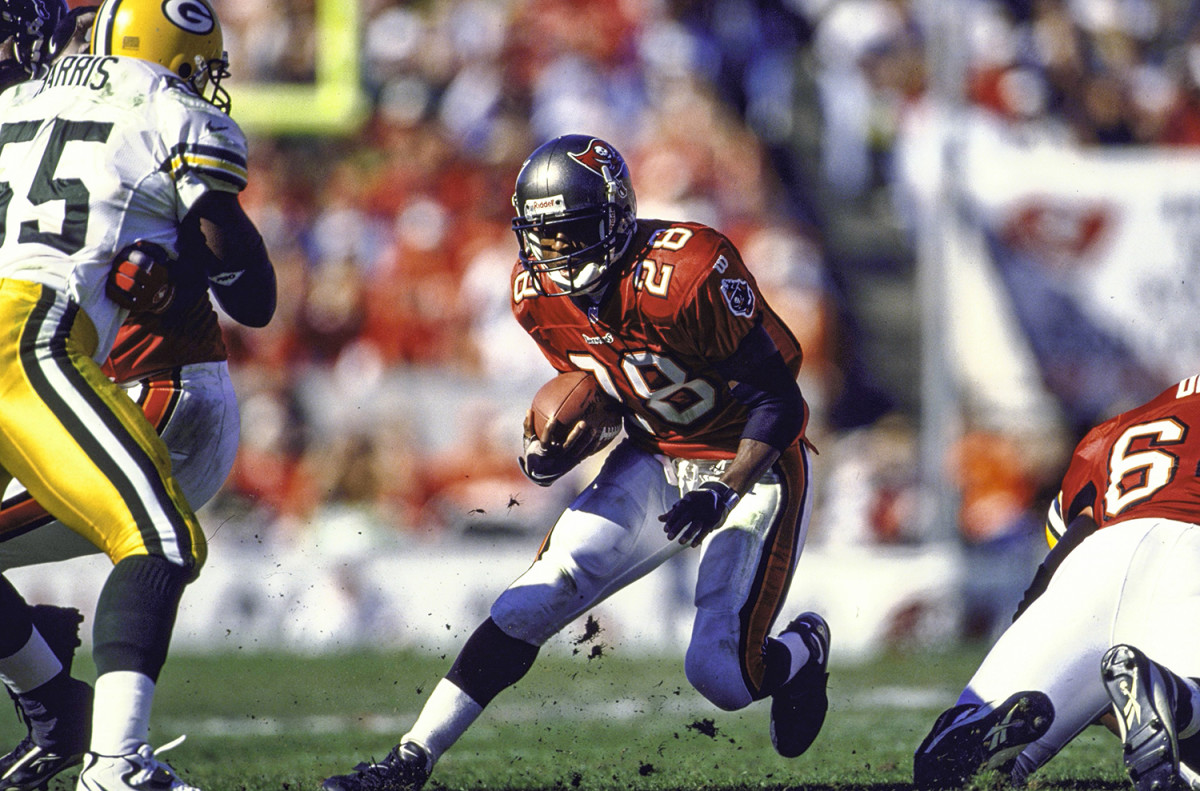

When the 5’9”, 165-pound Dunn arrived at Florida State from Baton Rouge’s Catholic High in the summer of 1993, he was so low on Bobby Bowden’s running backs depth chart that no one had even bothered to make a magnet with his name on it. Instead, dunn appeared on a piece of tape stuck to the bottom of Bowden’s board. The staff thought he might make a good defensive back. It took only a few practices, and run after run through the Seminoles’ Derrick Brooks–led defense, for his coaches to realize, as they liked to say, that you couldn’t catch Dunn in a phone booth. He was an All-ACC selection three times, then rushed for 10,967 yards and made three Pro Bowls during a 12-year career with the Buccaneers and the Falcons.

Throughout his time in Tallahassee, though, and then during his early years in the NFL, Dunn experienced a strange phenomenon: His old teammates kept talking about the good times they had experienced together, like the Seminoles’ ’93 championship season, but he found he couldn’t remember many specifics. When he was in his late 20s, he saw a therapist for the first time, and he came to understand that his memory lapses stemmed from the grief he continually experienced and hadn’t processed, stemming from a devastating night in 1993 he couldn’t forget.

Smothers was a single mother of six; Dunn was the eldest of her four boys and two girls. She worked as a Baton Rouge police officer and would supplement her $36,000 salary by doing private security. Each night Dunn would lie in her bed until she returned home, to whatever apartment they happened to be renting at the time, at which point he would sleepily go to the bedroom he shared with his brothers, knowing she was safe.

On Jan. 7, 1993, though, still in his mother’s bed, he was awakened by a phone call from another officer, a family friend. “I’m going to come get you,” the man told Dunn, then a high school senior. At the hospital Dunn received a call from the chief of police, who told him, “We’re going to do everything in our power to catch these guys.”

“My mom had been shot and killed,” Dunn says, “and I didn’t realize it until I hung up the phone and went to the next room, and I saw her body on a table.” Smothers, working one of her security jobs, had driven the manager of a Piggly Wiggly supermarket to make a night deposit at a bank, where her squad car was ambushed. She had been shot five times from behind. She was 36. (Three assailants were convicted in the crime.)

Dunn’s first thought? “I’ve got to go and make sure the younger ones, my brothers and sisters, are O.K.,” he recalls. “Right then and there, my mindset changed.” He didn’t have time then to mourn; his FSU recruiting trip, which he made, was just two weeks away.

Dunn and his grandmother suddenly had primary responsibilty for five young children—but they also had help. “The community started a fund for us,” he says. “They donated money, and that’s how we were able to pay bills all those years.” He thought a lot about what his mother would have wanted. “I knew what her dream was: to be able to put us in a position to where we had our own home, we had our own rooms, to create memories, have a place in which we can just grow.”

When Dunn was an NFL rookie in 1997, his coach in Tampa Bay, Tony Dungy, encouraged him and his teammates to become involved in the community. That Thanksgiving, Dunn sponsored three families who were moving into their first homes. “When I saw their reactions, it’s like, Wow, man, I just changed somebody’s life,” Dunn says. “I was like, I want to do this again.”

He did, and he hasn’t stopped since.

Dunn initially believed that his efforts would primarily benefit the parents, and they have; with their housing concerns eased, both Rickita Burney and Tia Merriweather are currently studying for bachelor’s degrees—Burney in criminal justice and Merriweather in communications—in addition to their full-time jobs. But he has learned, through studies he has commissioned, that the impact might be even greater on the children—467 of them, so far, one of whom is now the Texans’ quarterback, Deshaun Watson. “Because they now have a stable home environment, they’re able to do better,” says Jackson. “In school, their attendance records increase, their academic performance increases. They’re able to be involved in extracurricular activities because they’re able to have a stable schedule. And so the real impact we’ve been able to make is on that second generation in the home.”

Dunn’s connection with the families he has helped doesn’t end on move-in day. He is in frequent contact with them, both informally and formally. Tia Merriweather’s family, for example, has participated in the other three programs run by Warrick Dunn Charities: Count On Your Future, which provides financial training; Sculpt, which teaches healthy eating; and Hearts for Community Service, which awards $1,000 scholarships to students who volunteer. Her son Aubre received one of those scholarships; he’s currently studying journalism at Georgia State, and is on track to graduate in the same year, 2021, as his mother. “My goal is to be a news anchor for a major station,” Aubre says.

Even so, Dunn most relishes the days on which the families he sponsors arrive at their new homes. He has been there for 171 of the 174. “It really starts to hit me with the kids,” says Dunn, who lives in Atlanta and has a son and a daughter. “They have no idea what they’re getting. And then I can say, ‘Hey, this is yours. You can sit on your bed. These are your things. I mean, for me, those are the moments that it’s all about.”

The best moment of all is when the families spot the item that he has always insisted must await them on their new dining room tables. It is then, for a fleeting instant, that he can imagine that he has been transported back a quarter-century; and that the family who has been given a hand up, not a hand out, is his own; and that it is his mother at the head of the new table; and that she no longer has to work a dangerous second job in order to try to provide her children with a steady home; and that she is the one celebrating her family’s long-awaited good fortune by slicing each of her children a wedge of what has always been her favorite dessert.