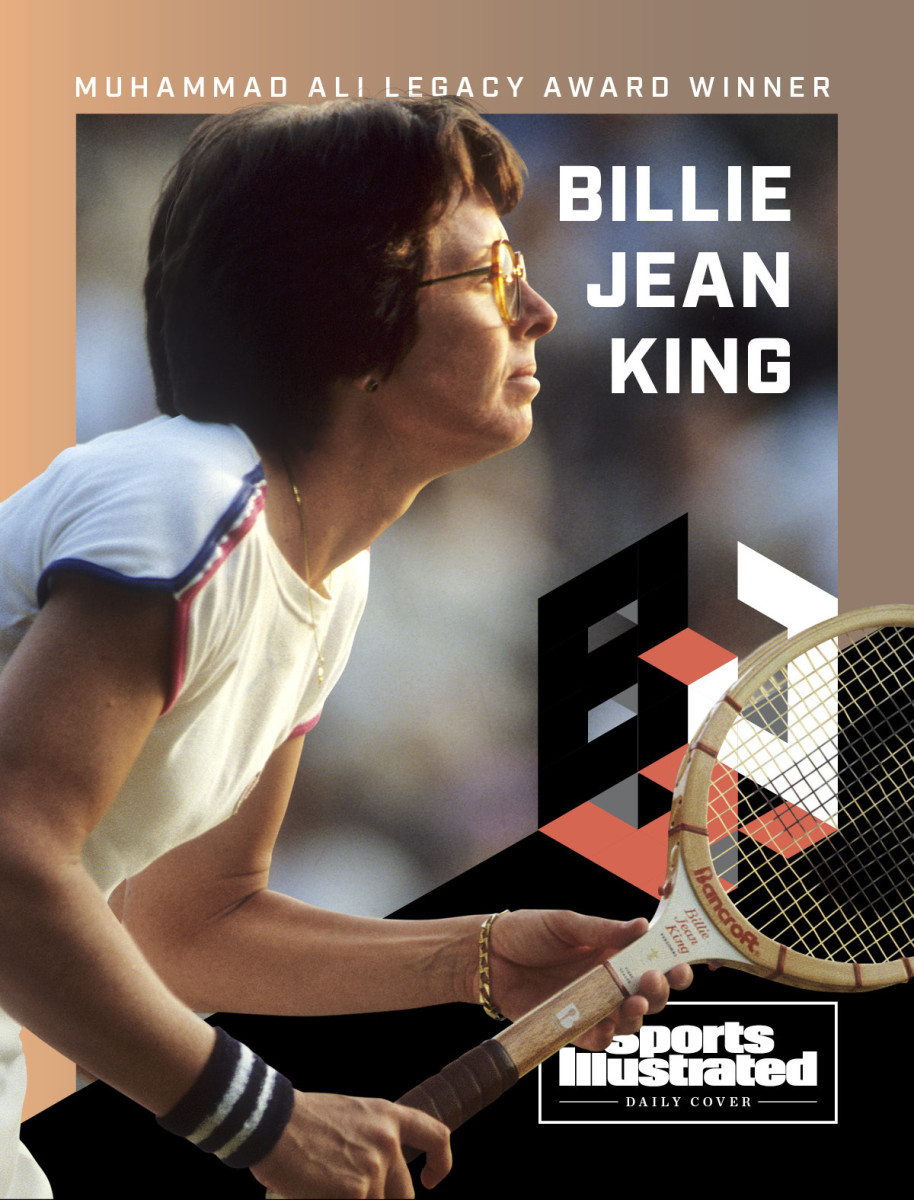

Billie Jean King Wins Sports Illustrated’s 2021 Muhammad Ali Legacy Award

The Muhammad Ali Legacy Award celebrates an individual whose dedication to the ideals of sportsmanship has spanned decades and whose career in athletics has impacted the world. This year’s winner will be honored at the Sports Illustrated Awards on Tuesday, Dec. 7, along with the 2021 Sportsperson of the Year. Tune in at 8 p.m. ET on SI.com and SI’s social media channels.

Inside Billie Jean King’s medicine cabinet hangs an index card. She affixed it there with Scotch tape so that she sees it every day when she goes to get her Listerine or face cream. In her handwriting is a quote from Coretta Scott King: “Struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.”

Billie Jean King has been able to see some of the progress she’s spent her life fighting for, but she also carries the battle scars. And on some days she feels so overwhelmed by the amount of work left to do that she doesn’t want to sleep, because that means one less day to get things done.

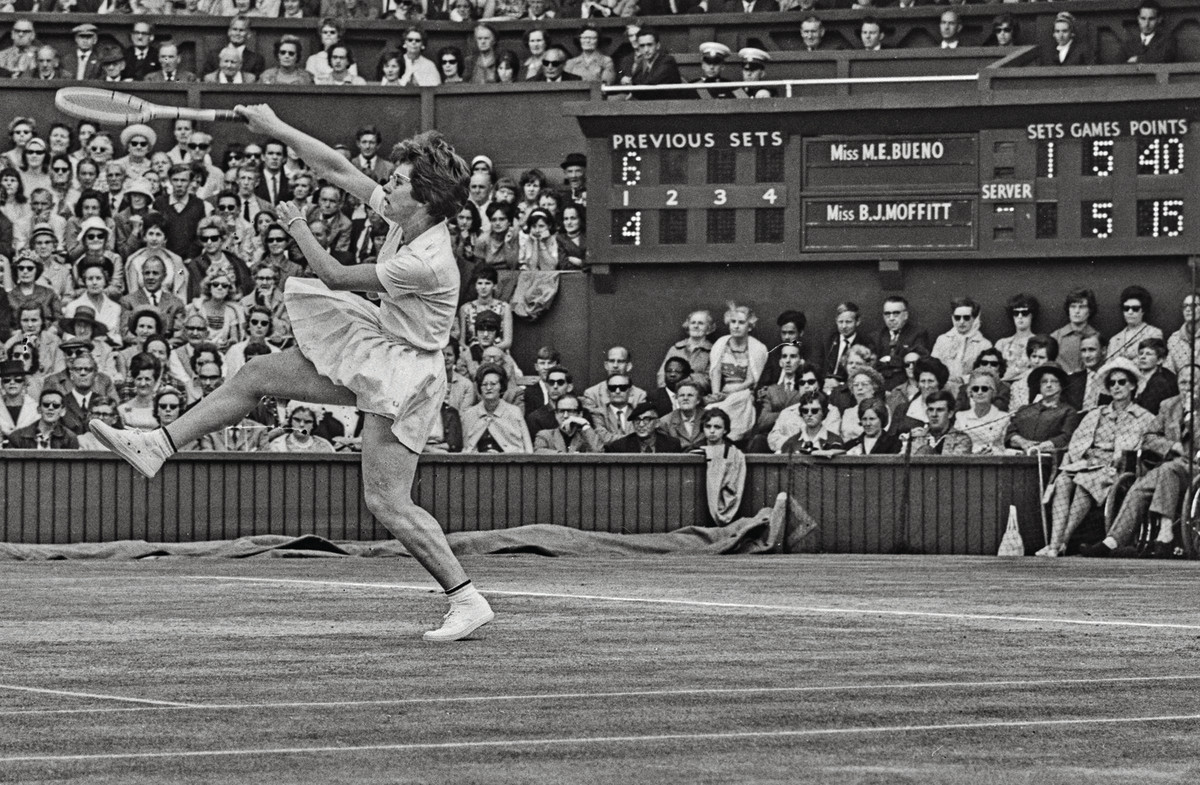

It’s with this energy that King bounds into a New York City studio space the day after her 78th birthday, as eager as ever to talk about so many topics that have little to do with her 39 Grand Slam tennis titles (12 in singles) or six years as the world No. 1. She is very prepared, wearing a blue blazer because she looked up Sports Illustrated’s colors in advance (blue and white) and asking about the college major of the person interviewing her (which she also looked up in advance). She takes the time to explain even well-known facts, like Moffitt being her birth name. She is always on message.

This doesn’t come across as contrived but rather as vestigial from an era when the opportunities for a female athlete to be heard were so rare that King had to nail every single one. Perhaps for the same reason, when she answers a question, the words tumble out. She can segue from an image from 1960, when as a teenager in Long Beach, Calif., she watched on TV as Ruby Bridges desegregated a Louisiana elementary school, to her present concerns, such as why the three female originators of the Black Lives Matter movement—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi—don’t get more attention.

“I have too much,” King says at one point, almost sheepishly.

Too much what?

“Information. Another year you live is another year of information, another year of history happening.”

And King feels all of it deeply. This is why her autobiography, All In, took nearly five years to complete: 900 pages had to be edited down to around 400. King hasn’t just lived through history. She has driven it, from the risks she and eight other players—aka the Original Nine—took in 1970 to start their own women’s pro circuit in pursuit of equal pay; to being the first female athlete to earn more than $100,000 in a single year; to becoming one of the earliest prominent openly gay athletes after she was outed in ’81 through a palimony suit filed by a former intimate partner who was a woman. The pain from her outing still stings.

Billie Jean King is this year’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award winner not only for leading the charge for gender equality during her long tennis career, but also for how she’s kept it up—fighting for women, but also for other causes, such as environmentalism and LGBTQ rights—in the nearly four decades since she retired. Her knees gave out on her, and for a long time she barely played the sport she once dominated, but King has never taken her eye off the ball.

The last time King was honored by this publication was in 1972. Title IX passed that year, banning sex discrimination in educational programs receiving federal funding, though it wasn’t yet clear how that law would transform women’s sports. A year later King would play Bobby Riggs in the Battle of the Sexes match, her triumph over the self-declared male chauvinist seared into the consciousness of 90 million viewers worldwide.

In the article naming SI’s ’72 Sportsman and Sportswoman of the Year—King shared the honor with UCLA men’s basketball coach John Wooden—she noted that many people consider her radical “but 10 years from now my ideas will seem antiquated.” (One of them regarded the playing of the national anthem at sporting events: “If the song offends some people, it is their privilege not to stand or acknowledge it.”) King was SI’s first female honoree, though in her telling she might not have been chosen if her sexuality had been known.

In All In, King describes an exchange with SI writer Frank Deford over dinner some 30 years after the honor. Deford said that when she was being considered for Sportswoman, managing editor Andre Laguerre asked him, “What’s this I hear about Billie Jean King being a lesbian?” Deford recalled saying, “Oh, Andre, they say that about all women athletes.” King writes, “Had Laguerre’s suspicions been confirmed, I never would have had a share of the 1972 award.” (Neither Deford nor Laguerre is still alive; Curry Kirkpatrick, who wrote the ’72 SOTY story, says he wasn’t involved in the selection of the winner.)

Whether or not Laguerre wanted a gay athlete on the cover of his magazine, he got one. Though she was then married to tennis promoter Larry King, Billie Jean was grappling with her own identity. She says she probably thought of herself as bisexual in 1972, noting, “We’re much more fluid than we think.” Seven years later she began her 42-year relationship with Ilana Kloss, now her wife, a former professional tennis player from South Africa (and King’s doubles partner). In 1981 the pair returned to their room at a resort in Florida and saw the door covered in pink phone message slips—which is how they found out King had been outed.

“Life was miserable then if you were gay,” King recalls, “and I was trying to figure out who I am.” She dismissed the advice of her lawyer and publicist and chose to acknowledge that she had had an extramarital relationship with a woman, her former secretary. King estimates she lost half a million dollars in endorsements and marketing deals in the first two months and millions overall, delaying her retirement plans. Not until she was 51, after an inpatient stay at a Renfrew Center for Eating Disorders that involved family and couples therapy, did King become truly comfortable with her sexual identity.

Around that time, King says Deford shared with her the discussion before the 1972 award. “I’m glad it’s not that way anymore,” King says, pointing to SI’s 2019 Sportsperson, World Cup champion Megan Rapinoe, the fourth standalone woman winner and an out gay athlete. King finds both validation and irony in being recognized again by SI a half century later.

“She’s very fortunate that she has actually gotten to experience that cycle,” Kloss says. “She’s said that when you read history, it feels so quick, but when you live it, it’s so much slower and harder. And boy, has she lived it.”

In the spring of 2019, Kendall Coyne Schofield and her fellow professional hockey players were fed up. The Canadian Women’s Hockey League had just folded, and the other women’s circuit in North America, then called the National Women’s Hockey League, didn’t pay a living wage. Coyne Schofield, a two-time U.S. Olympic medalist, earned $7,000 in the NWHL that season, and she was the highest-paid player on her team.

“We knew we couldn’t sit back and think that the landscape of women’s professional hockey was just going to change itself,” the 29-year-old forward says. “But we didn’t know how to create the change, because this is a daunting task. I thought, Who can help us create what this game deserves? It’s Billie Jean King.”

One phone call has turned into more than two years of King and Kloss’s advising the players as they launched the Professional Women’s Hockey Players Association. It’s the same fight King led five decades ago in tennis, when fewer tournaments were being offered for women than for men, with a small fraction of their purses.

Looking back at her tennis career, King wonders how much better she could have been had she just been able to devote herself to playing. When she attended Los Angeles State College in the early ’60s, before Title IX, she worked multiple part-time jobs to cover expenses. As she folded towels for minimum wage she was aware that, across town, Arthur Ashe (UCLA) and Stan Smith (USC) were on full scholarships. Later, in the prime of her career, King’s fight for herself and her peers meant she couldn’t focus solely on winning matches. King risked being banned from major competitions by the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association when she and the rest of the Original Nine boycotted a 1970 tournament that planned to offer women a 10th of the men’s prize money. In ’72, King won the French Open, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, but she skipped the Australian Open and her chance at the Grand Slam. She didn’t want to miss any events on the Virginia Slims circuit, which had been built out of the Original Nine’s stand two years earlier.

“I don’t know how good I could have been,” King, who retired from the game in ’83, says. “But I really cared about the other stuff because it’s lasting. Performance is fleeting. This can be lasting, and you pass it down to all these different generations.”

She actively works to make sure it does get passed down. The Women’s Sports Foundation, which King started shortly after the passage of Title IX, has invested around $100 million into ensuring girls have access to sports, conducting research about girls’ sports participation and serving as what King calls “guardian angels” for the landmark law. And she has helped others do for their sports what she did for tennis.

In the mid-’90s, Julie Foudy, then co-captain of the U.S. national soccer team, crossed paths with King at an event that brought together women leaders from different sports. As she heard King talk about the Original Nine and their fight for equal prize money, Foudy remembers thinking, This is our story! She and her teammates were frustrated: Even after winning the ’91 World Cup, the U.S. Soccer Federation was paying them $10 a day. So King challenged Foudy: What are you doing about it? You have the power!

Foudy was flying straight from the event to meet her teammates, who were about to sign another lowball contract. But she told them what King had said: that they needed to leverage their success and demand more, both in wages and investment in the sport. That’s how the USWNT has gone from those $10 per diems to six-figure salaries to suing the federation for equal pay.

“In women’s sports, for so long, you were told to shut up and just be grateful,” Foudy says. “And then we stopped shutting up, in large part because Billie’s like, No, it’s on you. You make the change. You as players demand better. . . . She really was the catalyst.”

In early 2019, King gave similar advice to Coyne Schofield and her colleagues. Speaking on a conference call, she urged 200 women’s hockey players to stick together as one. It was not all that different from the message King had delivered in a hotel ballroom in 1973, the week before Wimbledon, when she got 65 of her peers to vote unanimously to create the Women’s Tennis Association, uniting them in one tour that in 2019 awarded $179 million in prize money. (“I was in the room,” Kloss recalls, “and all I knew was that if it was good enough for her, it was certainly good enough for us.”)

The PWHPA started in May 2019 with no structure and no bank account. But not unlike the Virginia Slims circuit, it has organized barnstorming tours and has secured financial backing, including a $1 million sponsorship from Secret Deodorant and support from Billie Jean King Enterprises, an investment firm. Earlier this year the association held the first women’s pro hockey game at Madison Square Garden. King addressed the players before the puck dropped.

Like King in the ’70s, there are days when Coyne Schofield, who is training for a third Olympics, feels exhausted both by the work she’s doing for the future of the sport and by playing at the highest level. But she thinks back to the summer of 2019, when she and four other hockey Olympians attended the U.S. Open with King. They sat in the Queens tennis center named for King by the same organization that once threatened her career. They saw the equal crowds and equal prize money for men and women, which King first secured in 1973 by negotiating directly with the tournament director and lining up a sponsor to make up the difference.

“Everything is so equal and no one questions it, no one thinks about it. That’s just how it is,” Coyne Schofield says. “That was such a motivating moment, sitting in the empire that Billie Jean built and knowing that we have the opportunity to help create that in women’s hockey.”

Billie Jean King has been fighting the same fights for most of her 78 years.

“That’s where I go back to Coretta,” she says, referencing the quote in her bathroom cabinet. “It never ends. But each person hopefully helps. And allows a stepping stone.”

Kloss describes her wife as “a tree with thousands of branches.” King wants to go everywhere, help everyone, champion every worthwhile cause. Such as: After the U.S. Open’s tennis complex was renamed for her in 2006, she took steps to reduce its environmental footprint, and since ’08 the tournament has cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 37,000 metric tons. (In 2019, the Green Sports Alliance recognized King as a “true Green-Sports pioneer.”) In recent years, she has vocally backed athletes protesting police brutality and denounced laws banning transgender and intersex kids from participating in sports.

She often talks about an epiphany she had at age 12 at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, where she noticed that everything was white: white clothes, white balls, white people. She wondered, where is everybody else? Decades later she still sees so much inequity—like in the results of a recent survey co-sponsored by Billie Jean King Leadership Initiative, her nonprofit, showing that a majority of women of color in the workplace feel that stereotypes have hurt their careers, and that they are less likely to feel valued than white women. Disparities like these are why King still feels a daily urgency and worries, Kloss says, “that she is running out of time.”

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when King’s travel schedule was necessarily halted, Kloss suggested they return to the tennis court. King hadn’t really played for the better part of two decades, during which she had a double knee-joint replacement. The joy immediately came rushing back. Kloss says she’s never seen anybody more excited than King about the feel of a tennis ball on her racket. That feeling set the course of her life.

The day she turned 78, that’s where King was: on a court, doing a few extra drills, still working on that forehand. As a champion, King was always trying to hit the perfect shot, though she knew it was an elusive goal. But she kept trying, getting better, getting closer, just as she has in her pursuit of equality, her life’s work, her legacy.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Our No-Nonsense, Cut-the-Crap Guide to MLB's Labor War

• The Suns Have Won 16 in a Row. It's Been Spectacular.

• He Can Knock Out a World Champion From the Comfort of Your Local Library