What was lost on Centre Court

Federer as Religious Experience. That's the title of the essay on the Swiss tennis player Roger Federer by the great American novelist (and former junior tennis star) David Foster Wallace. The essay, published in 2006, attempted to capture the qualities of Federer's play; his balletic movement, his fusion of power and grace, and his exploration of seemingly impossible angles, spins and shots that seem to raise the five-time Wimbledon champion above the mundane, misjudged, and often flawed execution that so often characterizes tennis, as it does all human endeavor.

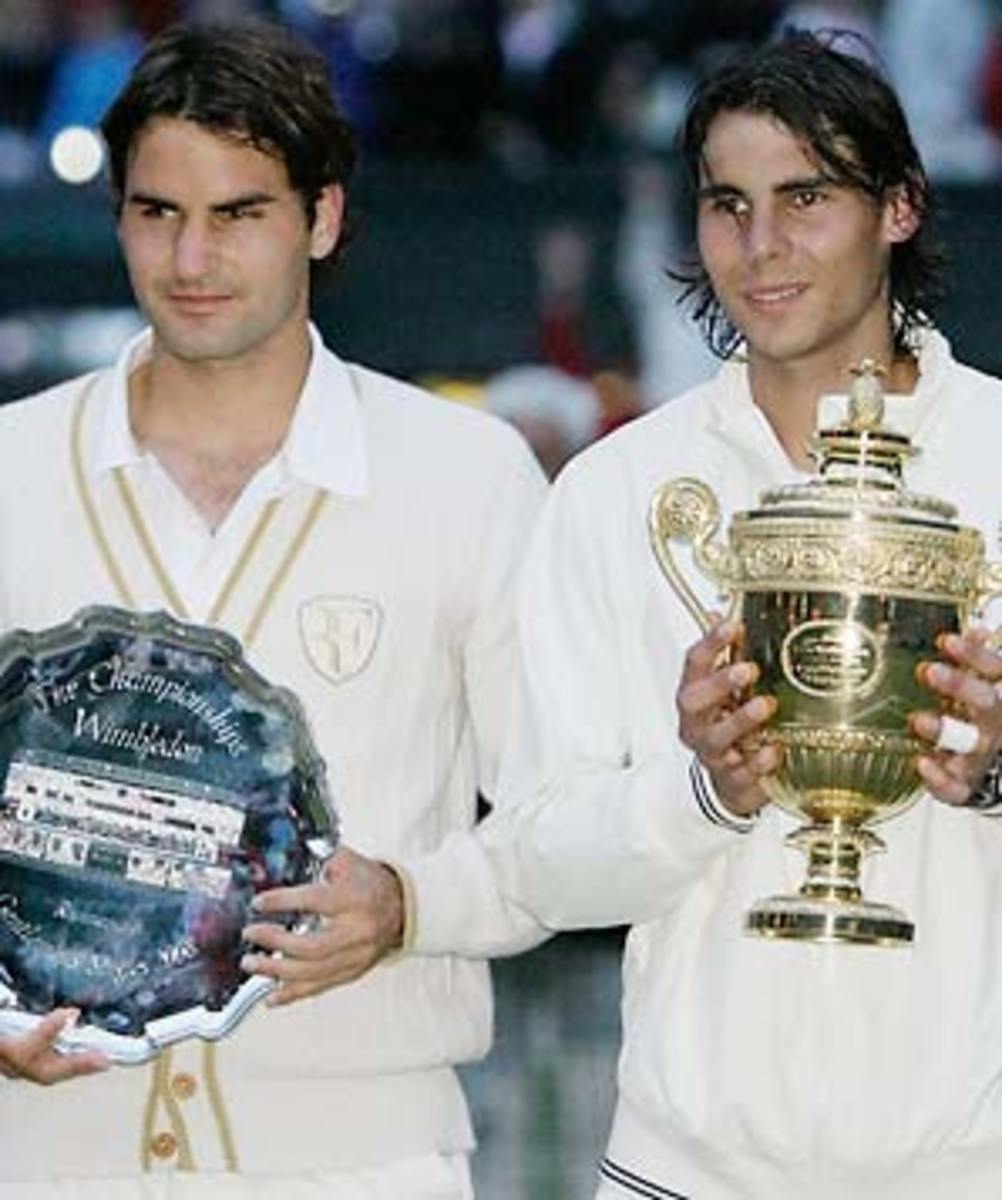

Wallace's ecstatic reverence for Federer became the definitive text for a legion of fans, in which I include myself, who have this last week suffered the blank and aching sadness that often accompanies the collapse of a belief system. On July 6, as I watched Federer lose a 4 hour, 48 minute five-set match to the Spanish superstar Rafael Nadal -- a match, that John McEnroe and Bjorn Borg both described as the greatest ever, played -- I felt a creeping realization as the duo battled into the twilight that I was witnessing something more profound than my hero losing a tennis match: I was witnessing the death of beauty.

For as much as even his own fans admire his play, there is nothing lithe, elegant or graceful about Rafael Nadal, oh he of bulging biceps and perennially itchy butt. Nadal has risen to the top of men's tennis with the brute strength and single-minded determination. He's a bruiser (case in point: in the final, he served 25 percent to Federer's body; Federer chose that aggressive line only four percent of the time). And he's a scrapper: he has a canny ability to use angles created by his opponent against them, employing shots that, while not quite good enough to end rallies, keep an opponent heaving balls back, often on the run, in a Sisyphean nightmare from which only an error can provide release. Tennis analysts call his style of play "counterpunching."

For three years now, Nadal has neutralized Federer's talents on clay courts. The pulverized brick at the French Open (tennis' slowest surface) allowed him to grind the Swiss down. But in two successive finals at Wimbledon, in 2006 and 2007, Federer had managed (just) to raise above Nadal on a surface that acted as cynosure for all his talents (Federer has an uncanny understanding of how to harness the living ground under his feet with shots that the grass seems to propel past opponents.)

But even on the hallowed ground of Centre Court, so often compared to a cathedral, Federer was humbled on Sunday by Nadal's dogged consistency and refusal to be awed by even his most artful plays. The victory upended the romantic (but now so obviously fanciful) belief that loose, creative, attacking play will triumph over obstinacy and revanchism. Watching Federer succumb to Nadal's will, I felt like I was watching an angel fall; Nadal grabbed his ankles and wrestled him to the ground.

So what now for us lost and suddenly godless Federer fans? Nadal is no Jimmy Connors, who supplemented his bullying play with verbal aggression on the court. He plays fair and is magnanimous in victory. And if his words are to be believed, he is as big a Federer fan as any (Nadal always says of Federer that he is the greatest of all time, an invocation of immortal skill that particularly appeals to Federer fans). Perhaps Nadal offers us a lesson: one must accept greatness in all its guises -- even greatness wrought of brute force.

And what now for Federer himself? The greatest fear will be that he will walk away from tennis as Borg did at age 25, after devastating losses to McEnroe in the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals, saying that he was no longer the best tennis player in the world so no longer felt the hunger to play. Chances are Federer, now 26, will stay on and embrace the challenge. And we should love him even more for it. Rolex -- one of this trilingual Swiss gentleman's main sponsors -- likes to run an advertisement with a picture of Federer and a caption that reads "unrivaled." To be unrivaled is also to be solitary, even lonely. Federer now has company. For better or for worse, he has joined the rest of us mortals struggling against our limitations, in search of a beauty just beyond our reach.

Eben Harrell writes for Time Europe.